New ‘Masters’ of Dutch Landscape. Photographs of the Most Man-Made Land in the World

Abstract

This article discusses the impact of the now legendary 1975 exhibition at the George Eastman House in Rochester, New York: New Topographics. Photographs of a Man-altered Landscape on photography in the Netherlands in general, and specifically with regards to the 2008 traveling exhibition Nature as Artifice. New Dutch Landscape in Photography and Video Art. It begins by going into several aspects of the Dutch landscape itself as well as the country’s strong tradition of landscape painting. Together, these two elements make the context of landscape photography in the Netherlands rather unique. The article then examines the evolution of a new landscape photography, with photographers and their projects grouped according to characteristics previously encountered in the photography of the New Topographics. By defining similarities and differences between photographs of the New Topographics and Nature as Artifice, the author will arrive at conclusions to her enquiry concerning whether the earlier exhibition in any way influenced the latter, and if so, in what way(s) this influence occurred.

Article

Introduction

The exhibition New Topographics. Photographs of Man-altered Landscape that took place at the George Eastman House in Rochester, New York, is perceived as having cast a shadow of turmoil over the photography of the man-made landscape produced in the decades following its aftermath. The 2009 reconstruction of the original exhibition (almost in its entirety), the reconstruction’s subsequent international tour outside the United States (shown in the Netherlands in 2011), the appearance of publications such as Reframing the New Topographics in 2010 and the project Landschaft. Umwelt. Kultur. Über den transnationalen Einfluss der New Topographics held in 2015 at the Museum für Photographie in Brunswick, Germany, and the present issue of Depth of Field #7 centered around this theme, collectively represent only a small sampling of the appreciation this exhibition has received.[1] The aim of the article at hand is to examine the potential impact of the New Topographics on photography in the Netherlands.

Since the 1980s, there has clearly been an increase in landscape photography that focuses on the man-made aspects of the Netherlands. Nineteen projects of this kind were gathered in the traveling exhibition and book Nature as Artifice. New Dutch Landscape in Photography and Video Art of 2008. [2] In fact, in 2009, Nature as Artifice was shown at the George Eastman House, adjacent to the New Topographics exhibition, which had just been reconstructed from the museum’s archives at this time. To discuss the impact of the New Topographics in the Netherlands within the framework of this article, I will limit myself to examining the Dutch photographic contributions to the Nature as Artifice exhibition, while at the same time trying to answer the question: Were the makers of these photo projects in any way influenced by the New Topographics?

Before addressing this matter, I will first go into several aspects of the Dutch landscape itself, as well as the country’s strong tradition of landscape painting. Together, these two elements make the context of landscape photography in the Netherlands rather unique. Then I will examine the evolution of a new landscape photography, with photographers and their projects grouped according to characteristics previously encountered in the photography of the New Topographics. By defining similarities and differences between photographs from the New Topographics and Nature as Artifice, I will arrive at conclusions in response to my enquiry regarding whether the later exhibition was impacted in any way by the former. Finally, after providing examples of what photographers themselves have said concerning their own work in relation to this topic, I will summarize in what way(s) this impact occurred.

New Topographics

The New Topographics exhibition in 1975 at the George Eastman House showed Photographs of Man-altered Landscape, as the subtitle says, using works by the photographers Robert Adams, Lewis Baltz, Bernd and Hilla Becher, Joe Deal, Frank Gohlke, Nicholas Nixon, John Schott, Stephen Shore, and Henry Wessel, Jr.[3] The photographs featured modern additions to the American landscape that had not been part of traditional landscape imagery, like suburban areas, industrial sites, modernist business buildings, and motels. Or, as the 1975 press release put it: ‘The most vulgar aspects of our society seem neutralized as the result of this topographic approach. The viewpoint is anthropological rather than critical, scientific rather than artistic.’[4]

What is typical of the viewpoint that is addressed in the title, is the fact that attention had shifted from the landscape as a pristine majestic nature or wilderness to places that previously were considered uninteresting for art, especially places where man had left his mark. Whereas in traditional landscape painting, nature controlled the scene and man lived in it in the humble position of a shepherd, farmer, or fisherman, in the photography of the New Topographics man thoroughly controls and shapes his environment. The New Topographics drew attention to the phenomena of industrialization, urbanization, globalization, and increased mobility. New types of buildings and environments resulted from modernization of the landscape, like industrial sites and highways, were new environments to be visually explored.

Although the New Topographics movement can by no means be considered ‘green’, it matches a growing concern in society as a whole for the environment. Three years before the New Topographics exhibition, the 1972 book Limits to Growth by the Club of Rome was published.[5] It is iconic for the alarm many people felt about the ecological crisis resulting from a century of industrialization, urbanization, explosive population growth, and globalization. The focus on the influence of man on his environment can be seen as one of the ‘cultural expressions on landscape, nature and the environment’ as a response to ‘the global environmental crisis’ that has been the subject of eco-criticism in the humanities since the 1970s.[6]

Landscape in the Netherlands

In this new interest in the role of man in nature, the Netherlands becomes an interesting case for several reasons. First of all, the Netherlands can be considered an extremely man-altered landscape; being a muddy, sandy river delta landscape, the land is extremely moldable and malleable and completely shaped by man.[7] Along with windmills, in popular culture or in the work of some artists, like Edwin Zwakman, bulldozers are iconic symbols of the Netherlands.[8] Some parts of Holland – the polders – are even created completely by man out of the sea. In the Netherlands, the notion of man-altered landscape is put to its extreme. Some, like landscape architect Adriaan Geuze, state that this aspect of ‘manufacturedness’ is central to the genius loci of the Netherlands in general.[9]

Furthermore, the Netherlands is one of the most densely populated countries in the world. In order to make the most efficient use of the small area of land, the use of the land is extremely systematized and structuralized. Geometrical shapes and grids are the result, which photographers of course love to visually explore. The Dutch are very good at industrializing their environment. Through large greenhouses, the influence of man on nature is expanded to the computer-controlled temperature, humidity, and even rhythm of day and night. Water management, for which the Dutch are internationally renowned, has made the muddy delta land into a complex hydraulic system.[10] Even the word ‘landscape’ itself entered the English language from the Dutch during the late sixteenth century. What is interesting about this is that the word did not refer to something natural, but was an administrative term that referred to a geographical entity that had to be ruled by someone.[11]

Last but not least, it is interesting to look at Dutch landscape photography in light of the fact that the imagery of the Dutch landscape has a strong tradition in painting. The second meaning of the word landscape when it entered from Dutch into English during the Dutch Golden Age was a scene that was pleasant to be represented in an artwork.[12] ‘Landscape’ as a new genre for painting spread in the seventeenth century from the Low Countries throughout the world and became a popular artistic nouveauté. The idea to make landscape itself the subject of an artwork and not the backdrop of a religious, mythological, or historical scene, as was previously the convention, was perceived with great enthusiasm internationally. Dutch painters like Pieter Brueghel the Elder and Jacob van Ruisdael took the genre to great heights. Thousands and thousands of Dutch landscape paintings were bought and distributed abroad. They are still hanging in numerous ‘landscape painting’ rooms found in museums around the world. Not only did they spread the artistic genre of landscape painting, but they also branded the Dutch landscape in a very strong way as an idyllic country of green meadows, cows, windmills, plenty of water, and all kinds of ships, with the typically cloudy Dutch skies above.

Artists of the nineteenth-century Hague School of painting took up this image of the Dutch landscape again and emphasized the poetic qualities of the Dutch green polder. [13]Even when early modernist painters like Vincent van Gogh and Piet Mondrian changed their style and explored the power of color, the motifs remained the same. The Dutch landscape image is still tremendously popular.

Around 1900, through mediation of foreign photographers, the stereotypical image of the Netherlands from painting entered Dutch touristic and pictorial photography as well.[14] Although in art and photography, modernism rejected the depiction of nature and the rural landscape as a motif for photography, the stereotypical image of the Dutch landscape from painting turns out to be persistent in popular culture. The Dutch keep on repeating it in popular culture on calendars, posters, and cookie tins. Foreign tourists come and eagerly search for the traditional image of the Netherlands. They overload the Internet with their holiday pictures, which are snapshot imitations of famous Dutch landscape paintings. It remains a challenge for Dutch landscape photographers to position themselves in relation to this visual stereotype.

The Industrial and the Urban

After the Second World War, human interest and social documentary photography were predominant in Dutch photography. Photographer Wout Berger (b. 1941) was an important pioneer in the 1980s to introduce landscape photography again in the Netherlands. Berger states that the 1978 photo book Cape Light: Color Photographs by Joel Meyerowitz influenced him to change his own photography. Before that, he made human interest and commercial photography in which people were central. In 1980, he bought a field camera and started to photograph landscape. In the following decades he experimented with various ways of working with the field camera and was known in the 1980s for working from tower wagons. The photo book Uncommon Places by Stephen Shore from 1982 was also influential for his work. This spirit of social documentary led to social and media controversy around a Dutch village that turned out to be built over an illegal dumping site for hazardous chemical waste. Political action was taken to clean up the most polluted sites in the Netherlands, and more than 1,000 sites were designated with a so-called IBS code by the authorities in 1983.[15] (Fig. 1) It was exactly this list that Berger took as a starting point for the subjects of his series and photo book Poisoned Landscape: Polluted Sites and Landscapes in the Netherlands.[16] Berger was struck by the contradiction that these heavily polluted sites sometimes turned out to be able to produce rather beautiful scenery. In his later work, like the Ruigoord series or harena aqua palus, the political aspect was pushed to the background or eliminated completely. He explored the visual qualities of the very detailed, egalitarian color images that the field camera produced.[17] Berger started to photograph man-altered landscape like the New Topographics did, but he did not know the exhibition by then. He was influenced by a contemporary of the New Topographics, Joel Meyerowitz, who worked much in the same spirit. Also, he was directly influenced by one of the photographers from the New Topographics exhibition: Stephen Shore. This was the way it went with other photographers as well.

|

Fig. 1 Wout Berger, Diemerzeedijk. IBS-Code 025-007. June 1986, from the series Giflandschap/Poisoned Landscape, chromogenic print, 40 x 50 cm. |

Berger had been working in North Holland – the province of the Dutch capital Amsterdam. In South Holland, the metropolis Rotterdam, with its extensive industrial harbor and its modern architecture that was newly built after the destruction of the Second World War, offered sites that were attractive for photographers of a new kind of photography. With a field camera transported on the back of his bike, photographer Jannes Linders (b. 1955) was a frequent visitor of the Rotterdam urban landscapes and harbor in the 1980s. In his early art academy years, from 1976 to 1981, Linders attended exhibitions by Lee Friedlander and Walker Evans at the Lijnbaancentrum in Rotterdam, which, according to him, influenced his work. Although he worked in a broad field of artistic production – he was a portrait, theater, and museum object photographer as well – he also made work in the genre of architecture photography, which in those days was regarded with little esteem because it was thought to be a serving form of photography. Through the Swiss magazine Camera, he learned about the innovative landscape photography by photographers of the New Topographics.[18]

Already in 1983, in the context of a commission for urban photography by the Amsterdam City Art Fund, Linders positioned his own work in the photography production of his time:

‘Looking at a large part of Dutch photojournalism, one can see that almost exclusively distorting wide-angle lenses, coarse grain and burnt-in skies which are made use of. These techniques have to do with social engagement of the photographer, but throughout the years have become so widely accepted that they rather often bury the actual subject and therewith lose their original power of expression. Of course, the human condition is also important in my photographs. However, I believe that this aspect can also, and maybe in these times even stronger, be expressed from the ‘other side’: the typical, graphical and psychological effect of the built environment itself. …. The photography I am engaged in occurs little in the Netherlands as far as I know. It is the searching of a balanced combination of information, aesthetics and emotionalism. What I strive for is a restrained monumentality, with photographs that ask for attention without forcing their content on the beholder.’[19]

Of course, as noted above, Wout Berger was also working with his field camera in a more withdrawn manner, describing a new kind of photography from his tower wagons. But it is clear that this way of photographing was still very uncommon in Holland. Commissioned by the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, Linders made a series of black-and-white photographs entitled Landscape in the Netherlands in 1988-90. (Fig. 2)

|

Fig. 2. Jannes Linders, On the A13 near the Delft-Zuid exit, 1988-90, from the series Landschap in Nederland/Landscape in the Netherlands, commissioned by the Rijksmuseum Amsterdam. |

It was the Rotterdam-based Perspektief gallery, together with its photo-theoretical magazine of the same name, which gave exposure to new forms of foreign landscape photography in the Dutch photography scene in the 1980s and positioned Dutch photography in an international context.[20] The work of Linders was internationally contextualized and positioned in exhibitions at Perspektief – for example, in the exhibition Stadslandschappen: Gabriele Basilico, John Davies, Jannes Linders, Gilbert Fastenaekens (Urban landscapes; 1986) and the event Architectuur & Fotografie (Architecture and Photography; 1986).

Breakthrough of the Anti-Monumental

The 1988-89 exhibition at the Stedelijk Museum in Amsterdam and the 1989 photo book Hollandse taferelen (Dutch scenes) by Hans Aarsman (b. 1951) put the landscape back on the agenda of Dutch photography.[21] (Fig. 3) This happened in the spirit of ‘restrained monumentality’ – as Linders previously called it – akin to the photography of the New Topographics. In 1988, Aarsman bought a camper van and drove around the Netherlands for one year to take pictures with a field camera that he put on the roof of the van, or sometimes from another elevated position (in some of the pictures, the blue van itself can be seen). He did not construct his scenes very consciously, but instead allowed himself to be led by coincidence and turned left or right as the occasion presented itself. Instead of monumental subjects or impressive events, he captured ordinary street corners, text signs, and people stopping for a chat. Even the weather with pale, slightly overcast skies formed a counter-image to the dramatic, ‘typically Dutch’ cloudy skies. It was the stereotype of the Dutch landscape from painting that Aarsman opposed with a counter-image. His photographs also formed a counterpoint to the social documentary photography that was popular in the 1980s, with people and social conflict often in the leading role and political convictions rhetorically communicated in a visual way.

|

Fig. 3. Hans Aarsman, Maasvlakte, from the series Hollandse taferelen (Dutch Scenes), 1988-89, digital file. |

Aarsman acquired the New Topographics exhibition catalogue, but only after he already had produced Dutch Scenes.[22] He mentions the photographic work of Stephen Shore as a source of inspiration. He also knew the work of Wout Berger, who worked with a field camera and also photographed from high positions. Along with the exhibition of Aarsman’s Dutch Scenes at the Stedelijk Museum (1988-89), it was the exhibition Landschap in Nederland (Landscape in the Netherlands) at the Rijksmuseum in 1990, with photographs by Jannes Linders and André-Pierre Lamoth, that meant a large breakthrough for and exposure of a type of landscape photography similar to the New Topographics to a larger audience in the Netherlands. The shock that Linders’ photography produced was expressed by the weekly newsmagazine Vrij Nederland (Free Netherlands), which was known for its attention to photography. This magazine wrote the bold headline ‘Not a soul to be seen’ above a review of Linders’ Dutch landscape photographs.[23] Comparable to the commission of the cityscapes by the Amsterdam Art Fund in 1982, Linders made these Dutch landscapes in the context of a commission by the Rijksmuseum, which regularly commissions new art that documents Dutch society and contemporary history.[24]

Another photographer who was important to other photographers was Henze Boekhout (b. 1947). He made fragmented impressions of environments with different camera techniques, viewpoints, and different printing and mounting techniques. On the exhibition wall, he poetically combined these different types of images into new, multi-image installations. An important aspect of his work is a democratic treatment of elements from the environment, which also reminds us of the ‘anti-monumentality’ of the New Topographics. In Boekhout’s work, no type of landscape, building or object was more important than others. He reacted to and photographed his environment in a purely visual and intuitive way and made it into an all-encompassing stream of visual poetry and surrealistic coincidences. His sources of inspiration range from the photography of Leonard Freed to Graham Beal’s book A Quiet Revolution: British Sculpture Since 1965 to drawings by the Belgian artist Léon Spilliaert.[25] Boekhout’s open-minded view of his environment culminated in his photo book Seconds First from 1993. This book was and remains popular among Dutch photographers and is also a source of inspiration to photography students. In 1992, a year before Boekhout’s book appeared, the influential event Wasteland: Landscape from Now On took place in Rotterdam. This exhibition, with its accompanying publication and events, is often mentioned by a new generation of photographers as important for an awareness of new types of landscape photography. It was not the event that made the New Topographics photographers famous in the Netherlands, since of the photographers in the 1975 exhibition only Lewis Baltz was present in Wasteland. However, we could say that seventeen years later the spirit of the New Topographics was evolved and elaborated in Wasteland. Old traditions of looking at the world and composing landscape imagery were overturned by different types of photography with different approaches to environments like industrial areas, wastelands, airports, or computer rooms. For many in the Netherlands, including photographers, this was the way to getting to know the works by Lewis Baltz, Gabriele Basilico, Michael Brodsky, Jean-Marc Bustamante, John Davies, or Jem Southam. From then on, the new type of man-made landscape photography became more common. Also, in the 1990s the photography of the Düsseldorf Photo School of Bernd and Hilla Becher, with photographers like Andreas Gursky, Thomas Struth, Axel Hütte, and Candida Höfer, became known in the Netherlands. The Bechers, who had participated in the New Topographics, spread the ideas and approaches originating from their photography to this new generation of German photographers. The pupils, however, introduced their own influences, such as choosing large, sometimes even monumental sizes and the extensive use of color where the New Topographics often worked in black-and-white.[26]

Non-places

In 1996, the presentation of Snelweg: Highways in the Netherlands took place at the Rotterdam Kunsthal, a collaborative project, installation, and photo book by Theo Baart (b. 1957) and Cary Markerink (b. 1951).[27] They presented the environment of the highway, a ‘non-place’ previously only meant for traveling from one place to another, as a subject and important place in itself, where new types of visuals, aesthetics, and even language could be experienced.[28] Cary Markerink, who had been influenced by the work of Stephen Shore, which he previously saw in the late 1970s, mentions the magazines Aperture, Camera, and Creative Camera as sources where he saw new kinds of photography that interested him.[29] In 1982, he saw a smaller, traveling version of the New Topographics exhibition at the B2 Gallery in London, which featured only works by Robert Adams, Lewis Baltz, and Joe Deal. A new type of environment was also studied by Theo Baart in his project Bouwlust.[30] (Fig. 4) Over the years, Baart had been photographing the village of Hoofddorp, where he grew up. This village lies south of Amsterdam near the Schiphol Airport. Due to the changing economy brought about by the fast-growing airport, the rural environment of Hoofddorp with its acres of wide-open space around it and its agricultural community was transformed into a suburb with new businesses, new housing developments with new types of architecture, and new types of inhabitants.

Geometry and grids

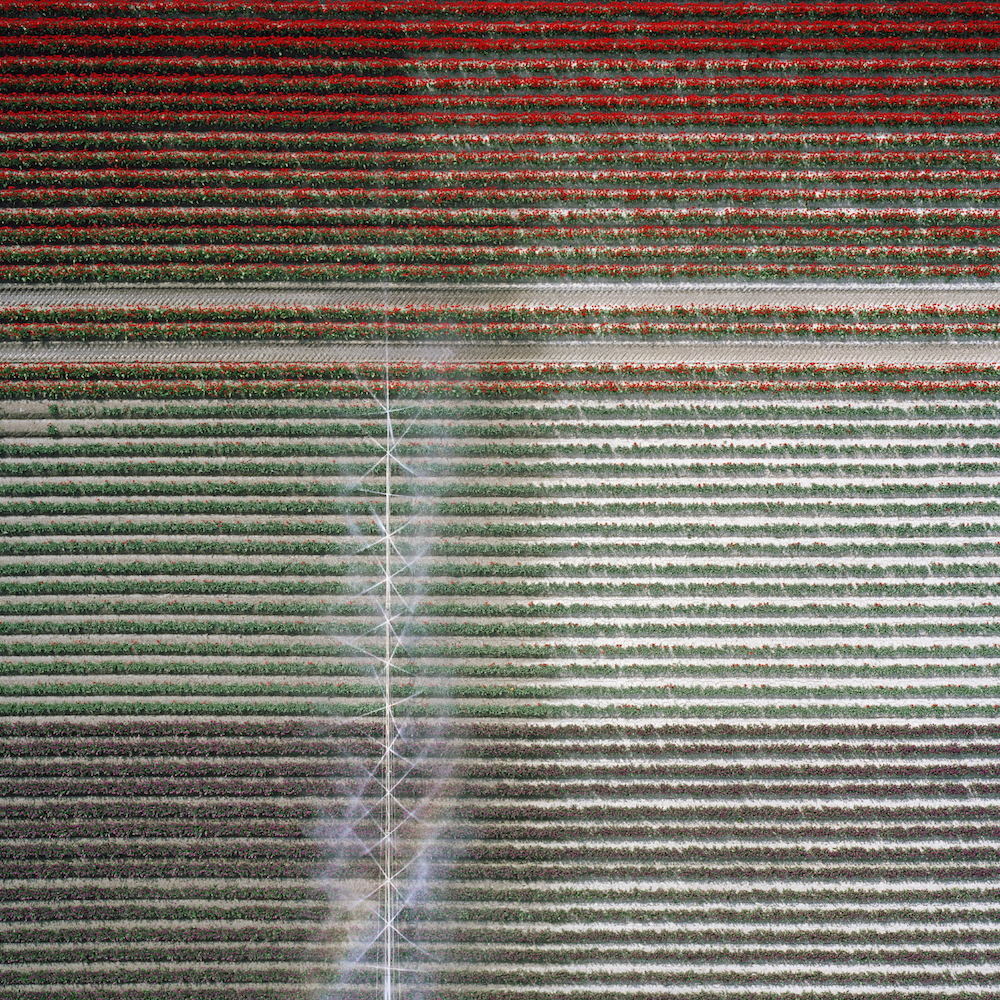

Often the consequences in the landscape of industrialization and human control are systemization into geometric patterns and grids. This motif has been explored by several photographers. Gerco de Ruijter (b. 1961 used remote-controlled cameras to make aerial photographs of the Netherlands. (Fig. 5) He especially chose places where the geometrical shapes conflict with natural forms, or where one can see nature growing back through and covering these geometrical patterns.[31] Also two artists from abroad, when working in the Netherlands, were struck by the highly controlled, systemized, and even computerized environments of the huge Dutch glasshouses – which in fact are factories that produce nature. The Hungarian artist Gábor Ösz (b. 1962) turned a caravan into a large camera by making a hole in one side and putting large Cibachrome papers on the opposing side. Ösz made nocturnal photos of landscapes with greenhouses. The light of the greenhouses reached the Cibachrome paper in the caravan over the course of exposure times that sometimes lasted for several nights. The resulting unique monumental photographs – in which the contours of the caravan can still be seen – show the greenhouses as gloomy places.[32] These pictures turned out to have registered a temporary phenomenon: due to environmental regulations, this nightly light pollution is no longer allowed, and the glasshouses are now covered or painted. The Spaniard Xavier Ribas (b. 1960) drew the viewer’s attention to the extensive size of the greenhouses. One continuous, unedited travelling shot was shown on a television screen, in which two former farmers who had moved to make room for the greenhouse talk about their past life at the farm. His installation is a visual comment on industrialization and large-scale agriculture as well as man’s treatment of nature.[33]

Leisure

The phenomenon of leisure being the modern widespread activity in which man intervenes in nature – instead of older activities like farming, fishing, and hunting – also became a subject for artists. Hans van der Meer (b. 1955) focused on the experience of the Dutch landscape through the activity of amateur soccer, and later on he photographed soccer fields all over the world.[34] (Fig. 6) Although Van der Meer became a renowned sports photographer because of this, with these projects he actually sees himself as a photographer of landscapes. The scenes are not chosen based on the nature of the game or the type of players. Instead, he chose these places on the basis of their backgrounds. In his monumental photographs and the photo book Artificial Arcadia, Bas Princen (b. 1975) drew attention to the artificiality of leisure in the landscape in two ways: in his photographs leisure itself is presented as an artificial experience of nature, but the environments themselves are also often unnatural. (Fig. 7) Leisure activities like artificial climbing, motor races, or camping take place in landscapes that were not meant for this purpose and often are temporary building sites not meant to be a landscape at all.[35]

Man-made nature

In Marnix Goossens’ (b. 1967) project Regarding Nature, the man-made character of the landscape is an aspect in the background. It focuses on the newly produced land, specifically on the polder Flevoland, which was created out of the water in the 1980s and the city of Almere that was created on that land. Goossens especially emphasizes the decorative aspect of the new nature in this environment, composing flowers on the two-dimensional surface or emphasizing the repeating rhythm of recently planted trees.[36] Another typical example of man-made nature, the park, was the subject of an animation installation by the artist duo Driessens & Verstappen (Erwin Driessens, b. 1963, and Maria Verstappen, b. 1964). In an animated film, they showed photographs made over the course of a year (January 2001 to January 2002) on exactly the same nine spots in the Frankendael Park in Amsterdam. With their work, they emphasize how nature, in this environment totally designed by man, manifests itself in the change of the seasons.[37]

Extremely controlled nature

The human manipulation of the land not only creates structure for the purpose of industry, trade, or leisure. Emerging from an interest in the over-regulation of the Dutch landscape, Gert Jan Kocken (b. 1971) shows a process of curing of the landscape by human hands in his series Enschede. After the landscape of part of the city of Enschede in the north of the Netherlands was severely damaged by a huge explosion of a fireworks factory on 13 May 2000, Kocken re-photographed the damaged site over the years from 2001 onward, when the event was no longer the focus of photojournalists.[38] The Dutch people’s care for every piece of their land was also the subject of the work Nieuwkomer (Newcomer; 2007-08) by the artist Arnoud Holleman (b. 1964). Holleman, who works as a conceptual artist in various disciplines and techniques, focused on the discussions by all types of related people to the building of two wind turbines in the area between The Hague and Amsterdam, where many, often conflicting, interests are at stake. On the website www.nieuwkomer.nl, Holleman combined photographs of these wind turbines with stories that can be heard by clicking links. Not only do we hear about the conflicting interests and the typical Dutch disputing and compromising (nicknamed ‘poldering’ by the Dutch themselves) between the many involved parties; there are also debates regarding whether these windmills should be seen as beautiful additions to the landscape or not, which depends on whether one views them as successors to the old windmills.[39]

The generic landscape

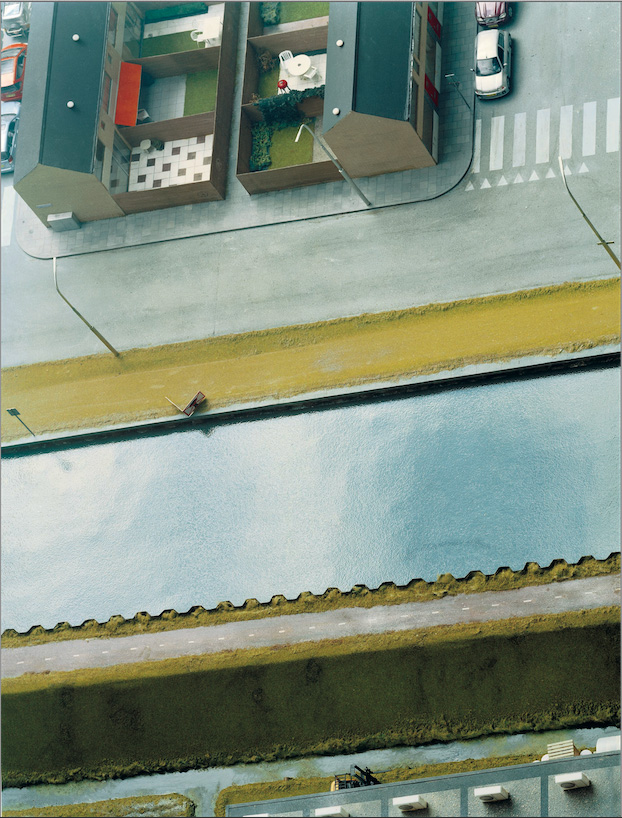

Some artists also tried to photograph the essence of the new urbanized and industrialized landscape. Frank van der Salm (b. 1964) does so by making his photographs slightly out of focus. (Fig. 8) Detail and specificity make way for the global shapes within the environments. By also giving his photos generic names like Square or Network, he tries to define types of landscape (or cityscape) instead of specific places. Edwin Zwakman (b. 1969) has a comparable interest in the generic modern landscape. However, he depicts it through a different approach and technique. In his studio, Zwakman constructs scale models of elements of the Dutch landscape. He does not work from concrete existing examples or photographs, instead he explores what the modern Dutch landscape is in his mind by building the models from his own imagination and then photographing them to make them look real. (Fig. 9) Moreover, he made these works during a period when he was working in a studio in England. Therefore, landscape elements like the electricity pylons in his photographs are often not accurate depictions of these structures in real life.

Similarities

So to return to our initial enquiries: do the photographs of Nature as Artifice look like those in New Topographics? George Eastman House’s curator Alison Nordström’s argument for a combination was that the man-altered aspect, which the New Topographics had pointed out as an element in the landscape, had been pushed to its extreme – not only in the focus of the Dutch landscape photography, but also in the landscape of the Netherlands itself: ‘All of the world will have to deal with the phenomenon that our environment is increasingly man-managed. In the Netherlands, artificiality is nature. Holland is the archetypical artificial land – it is the world’s future.’[40]

The similarities between the photographs from the New Topographics and Nature as Artifice lie in the subjects and the formalistic composition of shapes and lines on the two-dimensional surface. Photographers from both New Topographics as well as those from Nature as Artifice chose to photograph especially the urbanized and industrialized, as well as the infrastructure for travel and transport, which prior to this time were considered as ‘non-places’. An anti-monumentality in the matter choice of subject occurred precisely because banal, vulgar and ordinary elements and buildings were taken as subjects in the images, e.g. motels, gas stations, traffic signs, highways, glasshouses, and electricity pylons. At the same time, both photographs from the New Topographics as from Nature as Artifice reveal a preference for geometric shapes, grids and open compositions; the composition does not repeat or emphasize the frame that locks onto the scene, making it closed, as was often the habit in landscape painting. Instead, the photographs have shapes and lines that seem to continue on for an indefinite distance outside the frame, thereby opening the composition, with the photograph then appearing to be a small part of a more extensive structure. It is these characteristics, which had already been introduced in early twentieth-century Russian Constructivist and German Bauhaus photography, that make it ‘late modernist’ photography.

Differences

The most striking differences between the photographs of the New Topographics and those of the Nature as Artifice exhibition are on a formal level: whereas the New Topographics photographs were mostly in black-and-white and in rather small sizes such as 30 x 40 cm, the photographs from Nature as Artifice were largely in color, had monumental sizes or covered large surfaces of the walls as assembled installations. This increase in size of tableau-like landscape ‘photoworks’ was most famously introduced during the 1980s by photographers of the Düsseldorf Photo School, e.g. Andreas Gursky and Thomas Struth, who were also renowned and influential in the Netherlands. Clearly, photography had left the topographic and documentary realms of printed media in order to become a form of art that invited contemplation in a museum environment in the manner of a symbol or icon. Furthermore, differences between New Topographics and Nature as Artifice lie in the subject matter itself. As pointed out before, the Netherlands is a densely populated, sandy river delta landscape that has been completely shaped and controlled by humans. This makes the physical features of the landscape itself very different from the many vast untouched or essentially unalterable desert or rocky landscapes of the United States. The Dutch landscape is very flat and completely covered by man-made, refined patterns and grids for purposes of systemization. The Dutch are famed for their organizing skills and this is visible in the extreme predominance of straight lines and geometrical shapes that often give the land the appearance of a well-functioning hydraulic, infrastructural or industrial system.

Impact of the New Topographics on the photographers of Nature as Artifice

Because of the similarities, the photographers of the New Topographics may most certainly be seen as predecessors in spirit of the photographers of Nature as Artifice. However, as is evident from the various photographic projects described in this article, the influence of the 1975 exhibition at the George Eastman House was by no means direct. The work of one of the New Topographics, Stephen Shore, is cited by several of the Dutch photographers as being an influence, yet this is not because he participated in the New Topographics exhibition. His work, as well as that of other American photographers such as Joel Meyerowitz, who made landscape photography of the same type, reached Dutch photographers through photobooks and an occasional exhibition, e.g. at the Rotterdam-based Lijnbaancentrum. In the 1980s, the Perspektief gallery, as well in Rotterdam, devoted attention to new forms of landscape photography on a more structural level, culminating in the Wasteland. Landscape from Now On exhibition during the Rotterdam Photo Biennial of 1992, which brought the new anti-monumental landscape photography of the man-made urban and industrial environment to the Netherlands. This ‘late modernist’ approach has continually resulted in interesting work, including the other projects discussed in this article as well as those appearing after Nature as Artifice, such as Marie-José Jongerius’ (b. 1970) photographs of Maasvlakte 2 of 2012. (Fig. 10)

CV

Maartje van den Heuvel is an art historian and curator of photography at the Special Collections of Leiden University Library. She is currently working on her PhD on contemporary photography of the Dutch landscape at Leiden University.↑

Notes

1. Salvesen/Nordström 2009; Foster-Rice/Rohrbach 2010; Parak 2015.↑

2. Heuvel/Metz 2008. ↑

3. Jenkins 1975.↑

4. Press release, New Topographics exhibition, consulted in 2007 in the George Eastman House archives.↑

5. Meadows 1972. ↑

6. Clark 2011, p. xiii.↑

7. See Frits Gierstberg and Tineke de Ruiter, ‘Metamorphosis of a Malleable Land’, in: Bool 2007, pp. 191-245.↑

8. See for example Edwin Zwakman’s work Bruder (1996) a monumental photograph of 185 x 510 cm depicting two bulldozers, Heuvel, Nature as Artifice, p. 183. Bulldozers appear more often in the work of Edwin Zwakman, see Asser 2008.↑

9. Adriaan Geuze sheds his light on the character and the poetry of the Netherlands as a man-made land with reference to Dutch historical maps and paintings, among other things; Geuze 2005.↑

10. For the Dutch people’s relationship to the water as expressed in both the landscape and in art and culture, see Metz/Heuvel 2012. ↑

11. Schama 1995, p. 20.↑

12. Schama 1995, p. 20.↑

13. See for example Reynaerts 2008 and Dijke 2015. ↑

14. Heuvel 2015, accessed 15 September 2015.↑

15. ‘IBS’ is a Dutch acronym for ‘Interim Act on Soil Contamination’. ↑

16. Berger 1992 . ↑

17. Haijtema 2001.↑

18. Heuvel 2003. ↑

19. Heuvel 2003, under the heading ‘Beschouwing’/‘Discussion’.↑

20. ‘Architecture & Photography’, special issue of Perspektief magazine,1986.↑

21. Aarsman 1989.↑

22. Interview by the author with Hans Aarsman on 26 July 2006. ↑

23. Heuvel 2003.↑

24. In fact the documentary commissions of the Rijksmuseum were started in 1975 by the same curator, Wim Vroom, who was responsible for the commissions of the Amsterdam Art Fund at the Amsterdam City Archive in 1971 as well.↑

25. Heuvel 2008 , p. 62.↑

26. Gronert 2009.↑

28. Both the book and the exhibition Snelweg featured texts that can be read on signs near highways. ↑

29. Interview by the author with Cary Markerink, July 2007. Gierstberg, ‘Metamorphosis of a Malleable Land’, in: Bool 2007, p. 222.↑

30. Baart 1999.↑

31. Ruijter 2004. ↑

33. Heuvel 2008, pp. 268-279.↑

35. Princen 2004.↑

36. Goossens 2001.↑

37. Heuvel 2008 , pp.162-173.↑

38. Heuvel 2008 , pp. 256-268.↑

39. http://www.nieuwkomer.nl, 2007, accessed 16 September 2015.↑

40. Conversation of the author with Alison Nordström, 3 April 2007.↑

References

Aarsman, Hans (1989) Hollandse taferelen, Amsterdam (Fragment).

Asser, Saskia et al. (eds.) (2008) Fake but Accurate. Edwin Zwakman, Munich (Schirmer/Mosel).

Baart, Theo and Cary Markerink (1996) Snelweg. Highways in the Netherlands, Amsterdam (Architectura et Natura).

Baart, Theo (1999) Bouwlust: The Urbanization of a Polder, Amsterdam/Rotterdam (Ideas on Paper/NAi).

Berger, Wout (1992) Giflandschap: vervuilde locaties en landschappen in Nederland, Amsterdam (Fragment) .

Bool, Flip et al. (eds.) (2007) Dutch Eyes. A Critical History of Photography, Zwolle (Waanders).

Clark, Timothy (2011) The Cambridge Introduction to Literature and the Environment Cambridge UK (Cambridge University Press).

Dijke, Frouke van et al. (eds.) (2015) Holland op z’n mooist. Op pad met de Haagse School, Zwolle/The Hague (WBooks/Gemeentemuseum Den Haag).

Foster-Rice, Greg and John Rohrbach (2010) Reframing the New Topographics, Chicago (Columbia College Chicago Press).

Geuze, Adriaan et al. (eds.) (2005) Polders! Gedicht Nederland, Rotterdam (NAi).

Goossens, Marnix (2001) Regarding Nature, Amsterdam (De Verbeelding).

Gronert, Stefan (2009) Die Düsseldorfer Photoschule, Munich (Schirmer/Mosel).

Haijtema, Arno et al. (eds.) (2001) Zand water veen, Amsterdam (De Verbeelding).

Heuvel, Maartje van den (2003) ‘Jannes Linders’, in: Geschiedenis van de fotografie in Nederland, Depth of Field, 20, no. 35, http://journal.depthoffield.eu/vol20/nr35/f08nl/en,

Heuvel, Maartje van den and Tracy Metz (eds.) (2008) Nature as Artifice. New Dutch Landscape in Photography and Video Art.

Heuvel, Maartje van den (2015) ‘The Rise of Dutch Landscape Photography. How a Vision of Painting entered Photography’, Depth of Field, 6, no. 1, http://journal.depthoffield.eu/vol06/nr01/a03/en

Jenkins, William (ed.) (1975) New Topographics. Photographs of a Man-altered Landscape Rochester (George Eastman House).

Meadows, Donella (ed.) (1972) The Limits to Growth. A Report for the Club of Rome’s Project on the Predicament of Mankind, New York (Universe Books).

Meer, Hans van der (1998) Hollandse velden, Amsterdam (De Verbeelding).

Metz, Tracy and Maartje van den Heuvel (2012) Sweet and Salt. Water and the Dutch, Rotterdam (NAi/Kunsthal).

Ösz, Gábor (2006) Camera Architectura, Blou (Monografik Éditions).

Parak, Gisela (2015) Landschaft. Umwelt. Kultur. Über den transnationalen Einfluss der New Topographics, Brunswick (Museum für Photographie) .

Perspektief magazine, ‘Architecture & Photography’, special issue of 1986.

Princen, Bas (2004) Artificial Arcadia, Rotterdam (010 Publishers).

Reynaerts, Jenny (ed.) (2008) Der Weite Blick. Landschaften der Haager Schule aus dem Rijksmuseum, (Ostfildern/Munich: Hatje Cantz/Neue Pinakothek.

Ruijter, Gerco de (2004) Gerco de Ruijter, Amsterdam (Basalt).

Salvesen, Britt and Alison Nordström (2009) New Topographics, Göttingen (Steidl).

Schama, Simon (1995) Landscape and Memory, New York (Knopf).