On Both Sides of the Ocean – The Photographic Discovering of the Everyday Landscape. Analyzing the Influence of the New Topographics on the Mission photographique de la DATAR

Abstract

The influence of the American photographers represented in the now famous New Topographics exhibition (1975) on the orientation of European photographers from the 1980s is regularly presented as obvious, particularly in the context of the famous Mission photographique de la Délégation à l’Aménagement du Territoire et à l’Action Régionale (DATAR: Delegation for Territorial Planning and Regional Action, 1984-88). This statement raises some important historiographical questions on the conditions and the nature of this transnational relationship. It should be examined how and why a visual reflection on the North American territory, grounded in the New World’s own history and mythology, was also applied to the Old World. In order to develop a reflection on the relationship between two different periods and cultural areas, this essay moves in concentric circles, by analyzing the very nature of these two photographic moments, their relationship, their inclusion in a photographic history and more widely in the visual representation of the territory.

Article

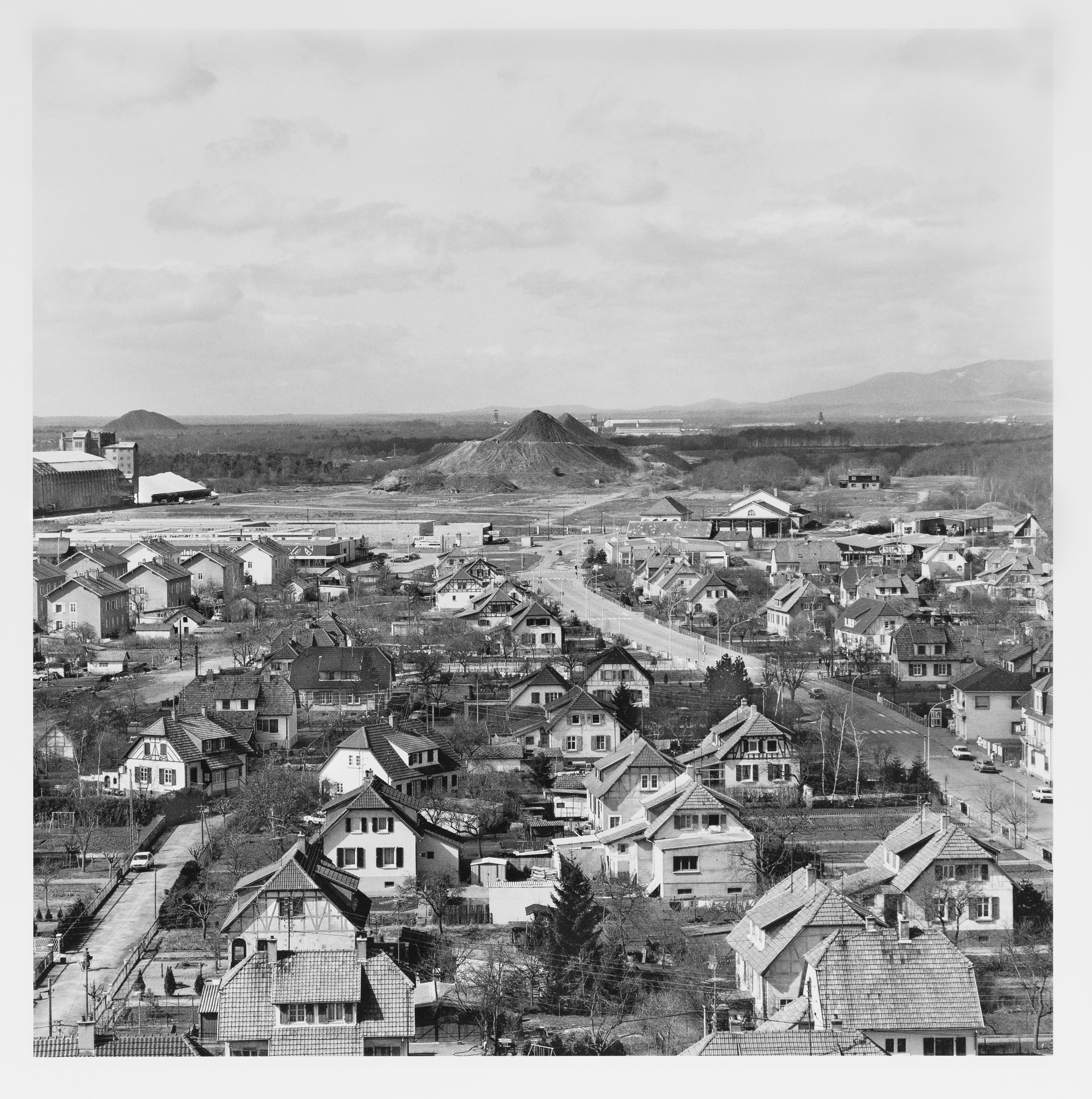

What link is there between a picture of a village in Montana and a city of southern France? (figs. 1 & 2) Between the large plateau of Colorado and the plains of Alsace? (figs. 3 & 4) What do these pictures, taken on both sides of the Atlantic – and ten years apart – have in common? The influence of the American photographers represented in the now famous New Topographics exhibition (1975) on the orientation of European photographers from the 1980s is regularly presented as obvious, particularly in the context of the famous Mission photographique de la Délégation à l’Aménagement du Territoire et à l’Action Régionale (DATAR: Delegation for Territorial Planning and Regional Action, 1984-88).

|

Fig. 1Stephen Shore, Second Street, East and South Main Street, Kalispell, Montana, 1974. © Stephen Shore, courtesy 303 Gallery, New York. |

|

Fig. 2 Jean-Louis Garnell, Albi (Tarn), 1985 / La Mission photographique de la DATAR. ©Jean-Louis Garnell / ADAGP 2015. |

|

Fig. 3 Robert Adams, Tract housing, North Glenn and Thornton, Colorado, 1973. © Robert Adams, courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco. |

Although it is not as clearly claimed at the time by organizers and theorists who were involved in the French project, this assertion became almost commonplace in the history of contemporary photography, without ever being questioned, or at least investigated.

The idea was easily accepted for several reasons, related to photography, territory and chronology. First of all, the history of photography: it was, since its very beginning, written on both sides of the ocean, in a transatlantic movement. Secondly, the territory: after World War II, profound transformations of territory and society shaped the US and Europe alike, and these developments also have had an impact on contemporary artistic production. In the US as well as in Europe, highways, shopping centers, power lines and residential areas have been scattered throughout the countryside, colonizing the green hills, thus disrupting any idyllic impression. American photography has reflected on these shifts with the work of Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange and other photographers working for the Farm Security Administration Project (1935-42). In the 1930s, European photographers like August Sander or Albert Renger-Patzsch started to document these changes too.[1] And finally, the chronology: the time-lag of nearly a decade between the American and the French works facilitates the tacit claim of causality between the two.

But, whether this statement is entirely right or not, it raises some important historiographical questions on the conditions and the nature of this transnational relationship. It should be examined how and why a visual reflection on the North-American territory, grounded in the New World’s own history and mythology, was also applied to the Old World. Is the New Topographics’ influence one of a transposition of style or a similarity in the process? Is it an American vision of the European area? Or is it the appropriation of style and method as demonstrated by the US American photographers by European photographers? It is time to question the conditions of the possibility of the emergence of a landscape representation and its national and cultural determinants, from the thought to the history of the territory of a medium.

In order to develop a reflection on the relationship between two different temporal and cultural areas, this essay will focus on two exemplary corpuses: the photographic work by the American exhibition of the New Topographics and their French counterparts, the photographers commissioned by the Mission photographique de la DATAR. It seems appropriate here to move in concentric circles, by analyzing the very nature of these two photographic moments, their relationship, their inclusion in a photographic history and more widely in the visual representation of the territory.

Two Different, Though Related Moments in the History of Photography

At first glance, William Jenkins’ 1975 exhibition New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-altered Landscape and the public commission of the Mission photographique de la DATAR conducted between 1984 and 1988 under the direction of Bernard Latarjet and François Hers have only little in common. Both events were formally very different: one gathered a dozen photographers while the other involved twenty-nine; one took place over a few months while the other extended over several years, one was accompanied by the publication of a modest brochure while the second gave rise to two voluminous works and an exhibition that enjoyed international dissemination. And finally one event remained very private at the time, while the other, on the contrary, worked to achieve greater acclaim. One may ask why these two events should be put on the same level. Despite these striking differences, the two events share the common point of being two important moments, two essential references in the history of contemporary landscape photography, marked by artistic ambition associated with a political issue.

Whereas the artistic quality was taken as self-granted for the US exhibition, due to the place of presentation, the artistic nature was often questioned as far as the Mission photographique de la DATAR was concerned. The status of the project, a public commission, still prompts suspicion of propaganda and state influence. In order to deconstruct these prejudices, it is necessary to review the history of the project.

The sponsor of the Mission photographique, the DATAR, was founded as an institution in 1963 and supervises territory planning on a national scale. It became a major player in the transformation of the country through the establishment of a policy of equipment and modernization. Early in 1984, the DATAR publicly announced the launch of a project of a new kind: a photographic mission. This project was conceived as an act of decentralization: at stake was the creation of a model of public action which purpose was to enable the institutions to take charge of the land’s interest in the landscape (community, national park, etc.). Furthermore, another objective of the Mission photographique was to support the artistic recognition of photography by its integration into the art world. From the beginning, the initiators claimed that photographers were artists, and photographs works of art.

The work presented at the George Eastman House in 1975 express in the same way political concerns related to the valuation of a renewed photographic aesthetic. Indeed there is a shift from environmentalism to ecological citizenship between the end of the 1960s and the 1970s. The defense of enchanted enclaves of wilderness leaves room for the call for individual responsibility and needs to state action to ameliorate environmental problems in cities, suburbs, and other everyday settings. In this context photographers of the New Topographics are part of an artistic movement that conceived images as part of a societal web. They ‘drew upon and helped usher in new aesthetic understanding of ecological citizenship’[2]

As such, both photographic incidents became paragons of their time. Even though the exhibition or the mission were only simple steps in the careers of the participants – and not the actual cause of the emergence of a school or style – they function as historical landmarks, which manifested the dynamics that were at work in the photographic landscape, at the crossroads of issues of territory and photography.

A Transatlantic Journey

How did the New Topographics’ photographs, along with some of their authors, cross the ocean in the early 1980s? Beyond institutional aspects, the photographers themselves created the most obvious links to set up the two photographic movements. From the very beginning, the Mission photographique displayed the work of Lewis Baltz in a poster of 1984, which additionally listed the photographic influences of the French project. The historian Jean-François Chevrier mentioned the New Topographics exhibition in his text La Photographie dans la culture du paysage (Photography in the landscape culture), published in 1985 in the first catalogue of the Mission accompanying the French work in progress.[3] So the manifestation was known and considered to be part of a living tradition in American landscape photography. This mention of the New Topographics by Chevrier belongs to a demonstration of the differences between the US and Europe, to underline an American continuity versus a French discontinuity.[4] This conviction at the time of a lack of vision of the landscape in France (which has been relativized since)[5] probably plays a role in the interest given to photographic creation on the other side of the Atlantic.

Concurrently, some photographers became aware of the New Topographics’ works even though their books were difficult to access, expensive to purchase and available only in a few libraries. Raymond Depardon discovered this American photography during his trip to New York in the summer of 1981, in particular the work of Walker Evans for the Farm Security Administration in the 1930s or Paul Strand’s book La France de profil (1952).[6] This influence is recognizable in his work Correspondances New-Yorkaises (1981), whenhe wrote ‘I want to make photos with a view camera. I want to make my family in the Dombes.’[7] Taking the example of these illustrious predecessors, he turned to the large format and decided to devote himself to the landscape, and especially that of his parents’ farm in Villefranche-sur-Saône. Back from the US, Depardon realized his series La ferme du Garet and showed a radical change in practice, style and subject. In 1981, Bernard Birsinger participated in a masterclass in Zürich with Lewis Baltz, and met Robert Adams.[8] The affiliation between how Adams looked at the Colorado plateau and how Birsinger looked at the plains of Alsace is striking. (figs. 1 & 2) From the start, Jean-Louis Garnell was very attentive to photography’s recent developments in the US. It is particularly through Sally Eauclaire’s The New Color Photography (1981) that he met the work of Stephen Shore and William Eggleston, which immediately influenced his still developing practice. (figs. 3 & 4) Garnell was one of the few photographers of the Mission photographique to work in a darkroom and in colour. Some of his pictures appear to be visual quotations from the work of Stephen Shore, similarly playing with the accumulation of commercial signs on roadsides, or those of deserted cityscapes.

In a second phase, the dialogue between photographers across the Atlantic is identified more directly with the participation of Lewis Baltz and Frank Gohlke in the second campaign of the French Mission photographique in 1987. The presence of the two American photographers in the premises and at the meetings of the Mission photographique opened an opportunity to exchange, to establish links of cooperation and even started friendships. This interpersonal dimension was probably stronger in terms of influence, but it is also more difficult to capture, evaluate and analyze.

A ‘Topographic Style’

In addition to these links forged between the participants, which allows the bringing together of those two photographic moments, we also must consider the joint statement of what one might call a ‘topographical style’. Walker Evans’ famous oxymoron, the ‘documentary style’, is taken up here and slightly shifted in purpose.

Indeed it can be considered that these works are the heirs of this reflection on the photographic creation from the first half of the twentieth century and formalized by Evans.[9] In the case of the Mission photographique de la DATAR, a poster executed in 1984 presents explicitly some of the main references. Among them, we can find some individual photographers: Frenchmen like Edouard-Denis Baldus, Eugène Atget, and Charles Marville, the German August Sander and the American Walker Evans. All are major players in the definition of ‘documentary style’. To resume here the description given by the historian Olivier Lugon, this means that the photographer favors a neutral posture, though he/she shows his/her specific perspective through the framing, composition or light, all these elements aiming to create a seemingly neutral whole, making up the illusion of ‘objectivity’.[10]

The question of the document is central in the visual experiments conducted in the US in the 1960s. The photographers offered a detailed documentation of the world but this time devoid of commitment or will to reform, contrary to their predecessors of the 1930s.John Szarkowski, director of the Museum of Modern Art’s photography departmentpresented the three most prominent representatives of this movement in the exhibition New Document in 1967: Diane Airbus, Lee Friedlander, and Garry Winogrand. Faced with this modernist aesthetic emphasizing the visual impact of the single image, conceptual artists of the same period used photography to criticize the art world and its codes. From 1963 on Ed Ruscha published books in which he brought together thematic series of images ‘without quality’. In this archival perspective, the work of Bernd and Hilla Becher, the only Europeans to participate in New Topographics, is a model of its kind.

In the early 1970s this part of the photographic production, which claims the quality of a work of art as well as the power of the document, is developed specifically toward the prism of the landscape. The genesis of the topographic tradition in photography became the subject of renewed attention in the years 1970 and 1980. Although known and disseminated for almost a century, the views of the West of Timothy O’Sullivan, William Henry Jackson and Carleton Watkins were rediscovered in the 1970s. Their pictures, taken mostly in the context of the ‘Four Great Surveys’, were of significant importance to the protagonists of New Topographics and constituted references. Similarly, in France, the launch of the Mission photographique de la DATAR was concomitant to the rediscovery of the Mission héliographique of 1851. This French public commission remained stuck in the silence of the archives before being updated by the work of curators and historians, the first of which being Bernard Marbot in 1979. A public presentation of this work was organized in 1981, and an article on the project accompanied the publication of the first work of the Mission de la DATAR. [11]This way of referring to nineteenth-century landscape photography also forms the basis for a critique of the photographic representation that dominated in the early twentieth century: the sublime tradition of the US or the picturesque tradition of Europe (see below).

To bring down the ‘mask of the charm of the landscape’,[12] the topographical aspect of the pictures was crucial for the way in which photographers on both sides of the ocean positioned themselves in the territory. In term of the subject, the curator and historian Britt Salvesen recalls that the use of the term ‘topographic’ is understood by Jenkins in the sense of the American Heritage Dictionary: ‘The detailed and accurate description of a particular place, city, town, district, state, parish or tract of land.’[13] In a more formal way, the historian Olivier Lugon describes the ‘documentary landscape’ as a ‘broad and overhanging view, that is to say a form where it is difficult [for the photographer] to impose its own brand to the composition.’[14]

It is striking that the series presented by Nicholas Nixon of Boston and Cambridge and Joe Deal of Boulder City and Albuquerque, as well as some pictures of Robert Adams of Colorado, perfectly fit this definition. (figs. 1 & 5) Similarly, in the French project, Gabriele Basilico saw his view of Tréport as exemplary of this perspective. (fig. 6) However, the topographic as a feature here seems more diffuse, punctuating the series of the photographers but never properly structuring them. We find traces of the topographic influence in some of the works of the DATAR’s photographers such as Jean-Louis Garnell, Raymond Depardon and Bernard Birsinger as mentioned above, but also Holger Trülzsch or Robert Doisneau. Trülzsch used a panoramic view of Marseille to present the structure of the city, and the great depth of field showed the coexistence of modern facilities with old neighbourhoods. The approach of Doisneau is spectacular in this change of perspective. The author of the humanist icons of La Banlieue de Paris (1949) retraced his steps, in large format and in colour, in photographing the ‘grands ensembles’ erected after the Second World War. The poetry of black and white gives way to an almost clinical observation of changes in these areas of the suburbs.

|

Fig. 5 Nicholas Nixon, View North from the Prudential Building, Boston, 1975. © Nicholas Nixon, courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco. |

|

Fig. 6 Gabriele Basilico, Le Tréport, 1985 / La Mission photographique de la DATAR. © Gabriele Basilico / Studio Gabriele Basilico, Milan. |

The American photographers, just like their European colleagues, grasped a form apparently obsolete, that of the topographic view, to invest it with a visual reflection on the contemporary. All used a ‘topographic style’ to picture their time with the greatest acuity. Their framed views were presented like ‘a meaningful whole, a network of traces and signs to decipher.’[15] The authors adopted a documentary-like neutrality, as promoted by Walker Evans, and offered a distanced and critical view on contemporary society through a formerly discredited genre: the landscape.

The Rise of the ‘Everyday Landscape’

Equipment and communication infrastructure, the emerge of consumer society, the rural exodus and growing urbanization have left a lasting imprint on the physiognomy of territories in al Western countries. On the traditional dividing line between the city and the countryside, areas with an indeterminate identity have been grafted, such as housing estates, supermarkets, warehouses. More recently these territories reveal other aspects, due to deindustrialization and economic crisis, with the extension and multiplication of urban ‘no man’s lands’. This modernization of the country has transformed landscapes and has created new ones. Facing these shifting, it seems necessary to reassess the meaning of ‘landscape culture’:[16] a set of mental representations of concepts, images, symbols and myths shared at a time on a territory by one ethnic group or nation. La Mission photographique de la DATAR, just like the works of the New Topographics participated in this broader movement of reflection on the landscape, its definition and its future. In both cases, the goal

Earlier in the century, the cultural geographer John Brinckerhoff Jackson became one of the leading thinkers with his interest in the ‘vernacular landscape’: how American habits altered the cities’ and suburbs’ appearances. He developed his reflection from the 1950s on, particularly through the magazine Landscape of which he was the publisher and editor between 1951 and 1968, and deepened it in his essay Discovering the Vernacular Landscape (1984). According to him, the reality of daily life could not be ruled out, under the precondition that it no longer corresponded to the conception that one had of the territory. His principle was that any landscape has a cultural meaning shaped by the people, and that it reflects their lifestyle and values in a tangible way. As such, mobile homes, gas stations, and billboards became part of the landscape. Jackson’s way of considering the landscape had a crucial impact on the thinking of geographers, anthropologists, architects and visual artists. Without detailing the various collaborations that have contributed to the development of new representations of the contemporary, it may be noted here that the 1975 exhibition’s subtitle A Man-altered Landscape in this regard clearly refers to this vivid discussion ignited by Jackson. The everyday landscape was already taken up by the zeitgeist and the photographers of New Topographics tried to grasp it, like those of the Mission photographique de la DATAR.

In the same way, the French project took part in an intellectual movement that exceeded the needs of the DATAR as an institution or the limits of the photographic field, with the emergence of a genuine landscape policy of which the Mission photographique was one of the first instalments. Indeed, the state institution was seeking to renew the modes of perception of the territory and the landscape, and the view from the ground appears to offer much richer possibilities than the formerly used map or view from above. The choice of perspective, which involved the fragmentation of perception and definition of a frame, was understood as a political process involving ecological, economic, historical and social stakes and above else aesthetic stakes. In a text commenting on the work of photographers in the 1989 catalogue of the Mission, the French philosopher and geographer Augustin Berque stressed how these photographic works foreshadow the birth of a new culture of landscape: ‘We are witnessing at this moment the birth of another landscape. And if that’s the case, then it is better that we help its birth by learning to do and see this new landscape, instead of diverting our gaze to illusory vestiges of the past, or resign ourselves to love Big Brother the parking…’[17] (figs. 7 & 8)

The Burden of a Legacy

Participating in the same effort, pleading for a landscape revival, US and French photographers were confronted with the same problem: the power of representations rooted in visual culture, associated with territorial and national identities. Through their repetition in various media, these images have become a true ‘landscape injunction’:[18] it is less about observing the environment than trying to adapt the representation, denying ‘what is’ in favour of ‘what might have been’. This leads to the reckless pursuit of an idealized vision, without conforming to a lived-in area, which is hit by invisibility, literally as well as symbolically. However, not everyone struggled with the same issues. François Hers, artistic director of the French Mission, reported this quote from the German photographer Holger Trülzsch, answering to the American photographer Lewis Baltz: ‘You do not understand the difficulty we have in Europe. We have centuries of representation of landscape painting behind us, and we must put together a Romanesque church, a phone booth and a petrol pump. We must manage historical and visual data more complicated than yours.’[19]

The New Topographics’ work also borrowed the legacy of the sublime and the American West, introduced by nineteenth-century painters and photographers. In the two decades from 1860 to 1880 five major artists photographers dominated the scene: Carleton E. Watkins (1829-1916), William H. Jackson (1843-1942), Andrew J. Russell (1830-1902), John Hillers (1843-1925) and Timothy H. O’Sullivan (1840-1882). Their work, mostly commissioned in the context of government expeditions the ‘Four Great Surveys’, or private ones (financed by railway companies), were largely inspired by the theory of the sublime formulated in the late 18th century by the philosophers Edmund Burke and Immanuel Kant. The photographers presented a virgin land to their contemporaries, a fascinating territory made of desert areas, of steep reliefs shaped by the elements, unfolding to the sight of the lone explorer. Despite this photographic inventory of an unsettled area, the ‘documentarian’ photographic description was always a form of imaginary construction, as the historian François Brunet says.[20] In fact, there is no trace in these images of the historical realities of the American West at the time, with for example the denial of the presence of Native Americans. Despite its fictional nature, the vision of the Wild West is relayed, as is known, throughout the twentieth-century literary and visual creation, and lastingly permeates our minds. The outlook of the Sierra Club photographers like Ansel Adams and Eliot Porter is exemplary to this point of view. Their work, which dominated the practice of landscape photography for decades, represented the West as a sublime and wild nature separate from humanity. It affected the way in which the New Topographics addressed, a century later, those same territories and questioned the landscape. Indeed the main problem were the ‘vernacular’ modes of appropriation of these so-called virgin lands. Here, the major concern is to observe the modern settlement.

In Europe, the issue was totally different. The landscape tradition was shaped by picturesque and pastoral models of representation. Without repeating the history of landscape paintings, we can assume that these landscape archetypes were informed and disseminated particularly through the cultural industry and tourism from the late nineteenth century and throughout the twentieth century. Engravings and later postcards were a vector for the establishment of these folkloristic visions, as well as guides and travel books. The ‘landscape injunction’ was then transferred mainly to sites that were remarkable and to heritage that was either built or natural. Abandoning modern buildings, even the spectacular ones, this visual heritage put excessive value on a hedgerow countryside and the Haussmanian city, ancient ruins and the Renaissance abbeys. The markers of post-war economic, technical and social development, namely industries and major infrastructures, remain off-camera and were excluded from this elective perception of the territory. Moreover, we can note that a large part of the reflection on the European everyday landscape was organized around its antithesis: the notions of commonplaces, and soon ‘non-places’.[21] In either case, those landscapes without any visible asset get their added value precisely from their ordinariness and familiarity. The work of the French photographer Tom Drahos is particularly exemplary from this point of view. (fig. 9) He composed mosaics from a set of clichés ‘without qualities’: they were distinguished neither by subject nor by shape. The photographer chose to photograph almost randomly, without framing, while travelling these territories without identity. All of them show the effects of a fragmented topography, in every sense of the word.

Disappointment and Crisis

Finally, what fundamentally brings together the work of American New Topographics in the 1970s and the work of the photographers of Mission photographique de la DATAR in the 1980s is their attitude with respect to the documentary tradition, in relation to the landscape tradition and finally facing the territory itself. An equation that led, on both sides of the Atlantic, to the opting for a topographic way. The topographic exploration of space was deliberately rooted in present time and was looking to avoid judgment as well as nostalgia. According to Britt Salvesen, photographs ‘reconcile beauty and ugliness, love and hatred, progress and degradation, and a host of other contradictions. They epitomize the paradox of indifference in being both boring and interesting.’[22] Her analysis undoubtedly also applies to the work of the European photographers. The neutral position of the photographer invites the beholder to get involved. In front of this seeming visual inventory, the latter has the responsibility to produce his own analysis. If environmental issues are present, none of the photographs underline attacks on landscapes. The photographers’ commitment takes the form of a statement without using visual effects. Nevertheless, through their ‘topographical style’, the landscape crisis becomes more visible.

CV

Raphaële Bertho holds a PhD in Art History and is a lecturer at the Tours University (InTru laboratory). Her teaching and research focuses on the aesthetic and political issues of photographic representations of the territory. She published La Mission photographique de la DATAR, Un laboratoire du paysage contemporain (French Documentation, 2013) and several articles including ‘Grands ensembles, Fifty Years of French Political Fiction’ (Etudes photographiques, 2014). Together with the curator Heloise Conesa she is the commissioner of an exhibition about landscape photography in France from the 1980s until today, which will be on display at the Bibliothèque nationale de France (French National Library) in 2017. ↑

Notes

1. Lugon 2001. ↑

2. Dunaway 2013, p. 14. ↑

3. Chevrier 1985a, p. 390. ↑

4. Chevrier 1985a, pp. 385-393.↑

6. Depardon 2010, n.p.↑

7. Depardon 1981, n.p.↑

8. Interview with Bernard Birsinger, 2015. ↑

9. Lugon 2001. ↑

10. Lugon 2001.↑

11. Néagu 1984, pp. 10-21. ↑

12. Chevrier 1985b, p. 27.↑

13. Salvesen 2009, p. 40. ↑

14. Lugon 2001, p. 216.↑

15. Lugon 2001, p. 216.↑

17. Berque 1989, p. 22: ‘Nous assistons en ce moment même à la naissance d’un autre paysage. Et si c’est le cas, alors il vaut mieux que nous aidions à cette naissance, en apprenant à voir et à faire ce nouveau paysage, au lieu de détourner notre regard vers d’illusoires vestiges du passé, ou de nous résigner à aimer Big Brother le parking…’↑

18. Bertho 2011. ↑

19. Interview with François Hers, 2007. ↑

20. Brunet 2007, p. 28.↑

22. Salvesen 2009, p. 37.↑

References

s.n. 1984, ‘La Mission Photographique de la DATAR’, La Lettre de la DATAR, n° 79.

Marc Augé 1992, Non-lieux. Introduction à une anthropologie de la surmodernité, Paris, Seuil.

Augustin Berque 1989, ‘Les Milles naissances du paysages’, in: La Mission photographique de la DATAR (ed.), Paysages, Photographies. En France dans les années 1980, Paris, Hazan, pp. 21-49.

Raphaële Bertho 2011, ‘L’injonction paysagère’, Territoire des images https://territoiredesimages.wordpress.com/2011/11/03/linjonction-paysagere(Accessed 8 February 2015)

François Brunet 2007, ‘Avec les compliments de F.V. Hayden géologue des Etats-Unis’, in: François Brunet and Bronwyn Griffith (eds.), Visions de l’Ouest. Photographies de l’exploration américaine, 1860-1880, Giverny, Musée d’Art Américain / Terra foundation for American art, pp. 11-28.

Jean-François Chevrier 1985a, ‘La Photographie dans la culture du paysage’, in: La Mission photographique de la DATAR (ed.), Paysages, Photographies. Travaux en cours, 1984-1985, Paris, Hazan, pp. 353-445.

Jean-Francois Chevrier 1985b, ‘Qu’est-ce qu’un paysage?’, Art Press n° 91, p. 27.

Finis Dunaway 2013, ‘Beyond Wilderness. Robert Adams, New Topographics, and the Aesthetics of Ecological Citizenship’, in: Greg Foster-Rice and John Rohrbach (eds.), Reframing the New Topographics, Chicago, University of Chicago Press.

Raymond Depardon 1981, Ecrits sur l’image. Correspondance New Yorkaise, Paris, Libération/ Editions de l’Etoile.

Raymond Depardon 2010, La France de Raymond Depardon, Paris, Seuil / Bnf.

John B. Jackson 1984, Discovering the Vernacular Landscape, New Haven / London, Yale University Press.

Bernard Latarjet and François Hers 1985, ‘L´expérience du paysage’, in: La Mission photographique de la DATAR (ed.), Paysages, Photographies. Travaux en cours, 1984-1985, Paris, Hazan, pp. 27-43.

Olivier Lugon 2001, Le Style documentaire, Paris, Macula, 2001.

Didier Mouchel and Danièle Voldman 2011, Photographies à l’oeuvre. Enquêtes et chantiers de la reconstruction 1945-1958, Paris, Le Pont du Jour / Jeu de Paume.

Philippe Néagu 1984, ‘La Mission héliographique de 1851, un modèle historique’, Bulletin de la Mission photographique de la DATAR, n° 1, in: Photographies, pp. 10-21.

Britt Salvesen 2009, ‘New Topographics’, in: Britt Salvesen (ed.), New Topographics, Göttingen, Steidl & Partners, pp. 11-67.