Whispers and Cries: Photographic Evocations of the Anthropocene

Abstract

This paper addresses the ‘problem of style’ that curator William Jenkins declared at the beginning of his catalogue essay on the New Topographics was ‘at the center of the exhibition’. It argues that rather than being ‘anthropologically’ detached, the New Topographics’ emotional reserve was a style. Its approach was consistent with contemporaneous New York painting and sculpture’s rejection of 1950s’ Abstract Expressionism’s emotional drama and allusive non-objectivity. Fusing 1960s’ Pop Art’s attention to mundane commodities and Minimalism’s reductive cubes, the New Topographics focused on geometric form and high contrast clarity applied to generic modernist suburban buildings. Yet their rejection of pictorial conventions of landscape in favour of environments strongly constructed by humans disrupted the ideal of nature as respite. Their banal urban and suburban landscapes featuring arrays of blocky factories and industrially manufactured residences present an early, implicit evocation of the Anthropocene. That work can then be recognized as a precedent to a prominent subject matter among current photographers of more overtly displaying our geological era’s disproportionate impact by humans on natural ecologies in images emphasizing the scale and extent of extraction, construction, consumption and waste.

Article

The entrances are shut. The garage doors rolled down. (fig. 1) The bright sunlight articulates crisp architectural clarity across the flat exterior span, but its proximity to the picture plane and absolutely balanced symmetry renders the scene inert. The picture’s genre is architectural landscape, yet it rejects historical landscape painting’s strategy of positioning tall trees to serve as a coulisse or framing device bracketing a vast recession of naturalistic textural variations – even in Ansel Adams’ Clearing Winter Storm, Yosemite National Park, California (1944) taking the form of widespread cliffs – to suggest the embracing arms of ‘mother earth’ welcoming one into an interior sanctuary.[1] Rather, the flat facade in Lewis Baltz’ Northwest Wall, Unoccupied Industrial Spaces, Skypark Circle, Irvine (1975) conjures a face with eyes perversely shut. Baltz’ photograph withholds from us access into those ‘windows of the soul’ – the inner spaces of either the structure or those who use it.[2] Northwest Wall epitomizes the style of the New Topographics – marked, and often remarked upon, as emotionally ‘closed’.[3]

|

Fig. 1. Lewis Baltz, Northwest Wall, Unoccupied Industrial Spaces, Skypark Circle, Irvine, 1975. Courtesy of the Estate of Lewis Baltz and Gallery Luisotti, Santa Monica, California. |

Richard Misrach’s photograph Hazardous Waste Containment Site, Dow Chemical Corporation, Mississippi River, Plaquemine, Louisiana (1998) also depicts a barrier to entrance. (fig. 2) The chain link fence and gate spanning the river and banks are more permeable – at least to sight – while also perilous, as centered within murky olive fog is literally a sign warning ‘danger’ – an icon of a male body crossed by a red diagonal – stating ‘contaminated area keep out’. The photograph’s title makes clear that the dense, obscuring atmosphere pictures potential suffocation, or poisoning, by pollution. While the mood, akin to the Baltz, is muted, the message in the Misrach is more overt. Privation is implicit in the sparseness, banality, and emotional austerity of images such as Baltz’s, who was one of the ten photographers represented in the 1975 New Topographics exhibition at the George Eastman House in Rochester, New York. It is more obvious in recent decades’ photographs of global environmental devastation and commercial imperialism. Rather than being radically distinct, the two photographic phases evoke laments for estrangement from undeveloped natural terrain that differ mainly in degrees.

William Jenkins, George Eastman House curator of New Topographics, opened his catalogue essay with the declaration, ‘There is little doubt that the problem at the center of this exhibition is one of style.’[4] The sober, mostly black-and-white work seemed puzzlingly radical by virtue of its very absence of radicality: no enigmatic abstractions such as by Minor White, no incorporation of lurid hues like William Eggleston, no drugged hipsters a la Larry Clark, no Surrealist overlays in the manner of Jerry Uelsmann, no candid American scenes by Lee Friedlander or vivacious street shots by Garry Winogrand. And as landscape photography, albeit of development, the other mode the New Topographics refused was the romance of nature. As historian Finis Dunaway has shown, through affiliation with the United States’ primary conservation group, The Sierra Club, Ansel Adams’ sparkling vistas and Eliot Porter’s intimate radiances served to promote harmonic convergences of the social and the natural. In 1955 the Sierra Club funded a group exhibition of black-and-white landscapes and animal studies, dominated by Adams’ work This is the American Earth, and in 1960 published the material under the same title with inspirational quotations. In 1962, the Sierra Club matched Porter’s vivid images with quotations by Henry David Thoreau for the wildly popular book In Wildness is the Preservation of the World.

In comparison to both cosmopolitan photographic innovation and conventions of landscape photography, New Topographics imagery such as by Frank Gohlke appeared distinctly deficient. From its tersely identifying title, Landscape, Los Angeles (1975), to its gray view of a miscellany of parked cars before a generic modernist office tower seen from across a wide street, the image signaled ‘detachment’. (fig. 3) Jenkins concluded his brief essay with the assertion that ‘The viewpoint, which extends throughout the exhibition, is anthropological rather than critical, scientific rather than artistic […] If ‘New Topographics’ has a central purpose it is simply to postulate, at least for the time being, what it means to make a documentary photograph.’[5]

|

Fig. 3. Frank W. Gohlke, Landscape, Downtown, Los Angeles, 1974. Courtesy of the artist and Gallery Luisotti, Santa Monica, California. |

Yet opening the lens to a less medium-specific perspective could have addressed Jenkins’ initial quandary. Contextualization of photographic ‘style’ within the concurrent modes of advanced painting and sculpture explains both Jenkins’ own interpretive refusal and his artists’ indirectness. From the earliest professionalization of expressive photography, it was ambivalently in conversation with painting, sculpture, and printmaking. Artists working in these media practiced in shared artistic and political/social worlds, even while photography, until the last couple of decades, had lesser status among critics, curators and collectors. In the post-World War II era, affinities across media are evident around 1950 in, for example, Harry Callahan’s a-focal close-up of leaves Chicago (1949), and Arshile Gorky’s The Leaf of the Artichoke Is an Owl (1944); in the jagged icicles of Minor White’s 72 North Union Street, Rochester (1958) and Clyfford Still’s abstractions suggesting ragged or dripping geologic crevices; and in the a-focal non-objectivity of Aaron Siskind’s photographs of exterior walls, stained, peeling and decrepit, and Willem de Kooning’s gestural abstractions.[6]

Consider how the Gohlke photograph described above channels Donald Judd’s stacked panels of just nine years earlier. (fig. 4) When we view New Topographic photography within the dominant style of broadly contemporaneous fine art, we can see that a source of its reductive visual language was the photographers’ adoption of forms by then prevalent in painting and sculpture, which by the mid-to-late 1960s had been codified as Minimalism. (fig. 5)

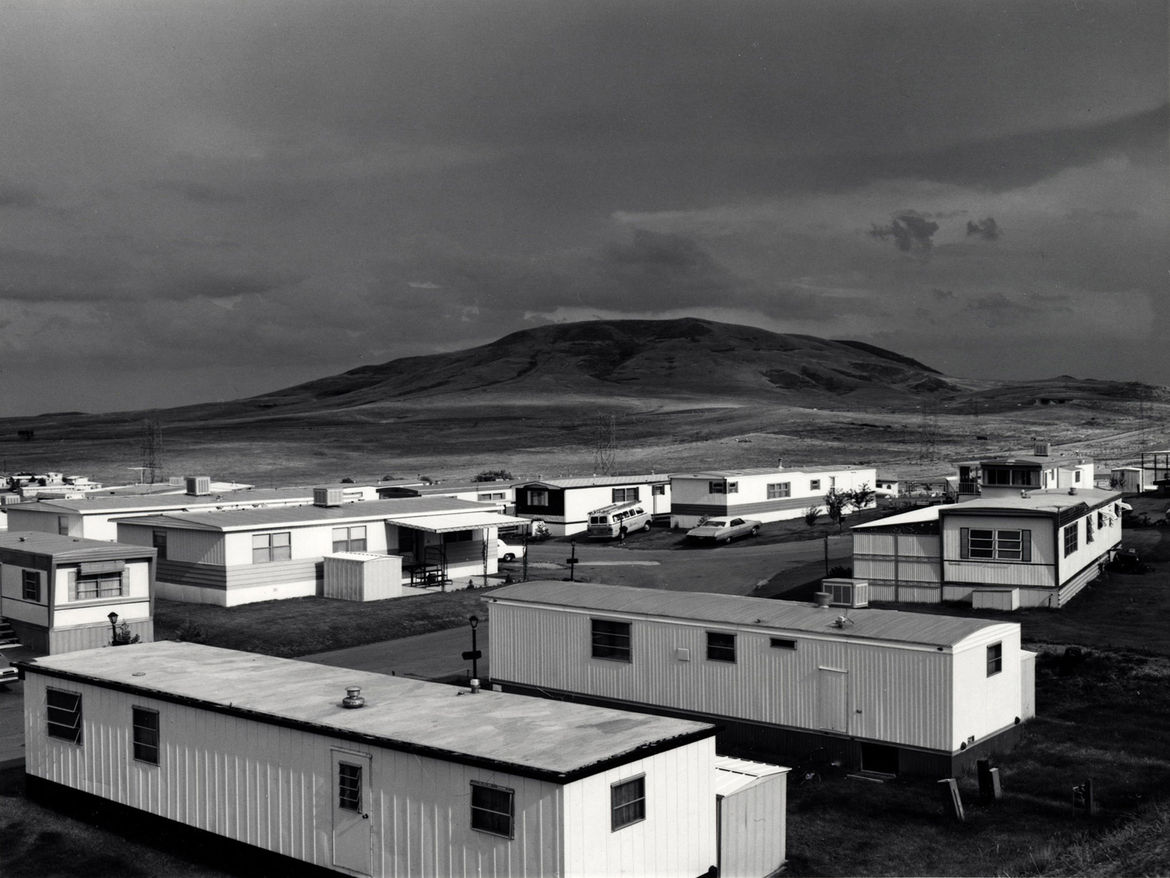

In this context, another archetype of that style, Robert Morris’ lateral, floor bound boxes, appear to have moved outdoors in Robert Adams’ rectangular cubic units of a trailer park, also viewed from a dramatic diagonal. (fig. 6) (Mobile Homes, Jefferson County Colorado, 1975 was prominently the first illustration in the New Topographics catalogue) Similarly, when Baltz made his 1974 South Wall, Mazda Motors, 2121 East Main Street, Irvine, famously avoiding incorporating his reflection in the large glass panes by standing directly in front of the central support, he performed the absence of figuration in Barnett Newman’s colour fields structured only by a few vertical strips. Of course, Bernd and Hilla Becher, the German duo whose collaborations were exhibited in New Topographics, made direct use of the modernist grid as seen in Andy Warhol’s individually framed Campbell’s soup cans and Sol LeWitt’s sculptural investigations of systems.

|

Fig. 4. Donald Judd, Untitled, 1965. Galvanized iron, 7 units, each 23 x 101.6 x 76.2 cm. Moderna Museet, Stockholm, Sweden. © Judd Foundation. Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY. |

|

Fig. 6 Robert Adams, Mobile Homes, Jefferson County Colorado, 1975. © Robert Adams, courtesy Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco. |

The New Topographics’ procedure of closed doors and emotional reserve was clearly open to the new formal strategies that came to prominence the previous decade of rejecting the perceived emotional excesses and non-representational abstraction of postwar expressionism in favour of structurally reductive geometries in impersonal formats. The painters’, sculptors’, and photographers’ cerebral, emotionally contained works, and even the curators’ consistent refusal to address the affective qualities of these works, demonstrate what critic Robert Pincus-Witten recalled as ‘the high formalist cult of impersonality’ of the 1960s and 1970s, in which ‘All personal reference, exposed personal reference that is, was covert in this machine of closed judgment.’[7] Environmentalist commentary had to be disguised or whispered.

In painting and sculpture, that formalist orientation can be understood as continuing the emphasis on the stylistic self-reflexivity of Modernist experimentation. But because the photographers’ application of reductive geometries to both the subject matter of plain generic modernist commercial and residential architecture and overall compositional structures was applied to the genre, broadly speaking, of landscape, the scenes signaled a discomfiting distance from, even loss of, the experience of nature. In relation to landscape imagery’s customary felicitous reciprocity between humans and other life forms, and reverential spirit toward nature, the artistic language of Minimalist austerity and the subject matter’s plethora of charmless boxes for residing and working call up the desolation following the biblical Expulsion from Eden.

Historically, landscape images, as literary and art history theorist W.J.T. Mitchell noted, ‘reflected a time when metropolitan cultures could imagine their destiny in an unbounded ‘prospect’ of endless appropriation and conquest.’[8] By the mid-1970s, following the nationally debilitating Vietnam War, after the crisis of the Middle Eastern OPEC withholding of oil, and in period of worldwide economic deflation, societies’ post-World War II economic recovery and optimism about the future had severely contracted.

At the time of the New Topographics, the reconfiguration of nature by humans, which some scientists and historians set to have begun with the ancient Greeks, some with the Renaissance expansion of banking, business and global explorations, most with the nineteenth-century’s acceleration of industrial development and production, was a prominent social theme. The 1962 publication of biologist/journalist Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring, exposing industrial chemicals’ poisoning of the public water supply, caused a sensation that sparked the social transformation of the nineteenth-century practice of genteel conservation of undeveloped lands into protectionist and politicized environmentalism. Bob Dylan, a folksinger becoming a rising star, propelled Carson’s theme by warning of ‘the pellets of poison… Flooding the waters’ in his 1963 song A Hard Rain’s A-Gonna Fall. Along with Cold War fears of defoliation by atomic warfare and by chemicals during the Vietnam War, and Paul Ehrlich’s foreboding Population Bomb (1968) predicting future widespread famine, concerns for the earth’s vulnerability stimulated the beginning of western culture’s environmental conscience.

In the preceding history of photography, regrets in relation to humans’ power over nature were rare. Gustave Le Gray’s dramatic vista of rows of smoke-spewing buildings cut into the terrain between a coal-blackened foreground and deforested hillsides suggests that his title of Factory, Terre-Noire (Black Earth, 1851-55) implicates more than just the locale’s name. (fig. 7) More characteristically, Le Gray’s radiant seascapes and crisp tree studies in the Forest of Fontainebleau, demonstrations of his experimentations with composite printing and waxed negatives, evince his deep feeling for nature. In contrast, Andrew Russell’s 1869 depiction of western United States train track construction adjacent to a mountain of rocky with erect nipple demonstrates human industry’s urge to match, and increasingly, to dominate, nature’s power and monumentality. (fig. 8)

|

Fig. 7. Gustave Le Gray, Factory, Terre-Noire, 1851-55. Salted paper print from a waxed paper negative. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles, courtesy of the Getty’s Open Content Program. |

In our century, this disproportionate relationship has come to be indicated by the geological designation ‘the Anthropocene’. Prominently used by the atmospheric chemist and Nobel laureate Paul Crutzen in 2000, the term ‘Anthropocene’ is intended – as yet, unofficially adopted by international geologists – to supersede the Holocene era. It describes the idea of a new geological epoch in which the human impact on the planet as biological and geological agents has become so great that the collective action of the species is found in the geological record.

The concept of the Anthropocene can be analogized as a scientific explanation for a constructivist view of nature. By recognizing the extent to which human agency is altering the ‘natural’ world, the distinction between ‘nature’ and the ‘natural’ on the one hand and ‘culture’, ‘humankind, and the ‘social’ on the other hand erodes. Scholars such as Timothy Morton and Bruno Latour challenge the nature/culture dichotomy as constructions, respectively, of language and of politics – ‘The idea of nature is getting in the way of properly ecological forms of culture, philosophy, politics, and art.’[9] ‘Nature’ can be considered constructed two senses: materially altered by humans’ strong presence magnified by our tools and technologies, and intellectually, by our linguistic framing of it into terrains and moods such as ‘wilderness’, the ‘pastoral’, the ‘sublime’, and the ‘beautiful’.

As rendered in their new landscape focus on developing exurban and suburban scenes, New Topographics images can retrospectively be recognized as a first phase of photographic awareness of the anthropogenic imbalance. Jenkins’ assertion of the scientific neutrality of his artists’ perspectives – not imagined ‘topos’ but straightforward ‘graphic’ realism – ignores, and contradicts, the images’ evocations of barrenness. The generic late modernist corporate architecture of offices and warehouses, sites of creeping corporatization of open space and constructed emptiness occupying former landscape terrain, illustrate interpersonal alienation; the structures these photographers turned their lens toward suggest not homes, but houses, less comfortable enclaves than isolation chambers. The underlying disquietude is so consistent across the oeuvres of the New Topographics that whether or not it is their conscious intention, they convey loss of faith in the mid-twentieth-century lifestyle and environment in an ambitious, developed country.

Revisionist accounts of this exhibition recognize this, describing its ‘especially elegiac tone and allusion to issues then taking form in the burgeoning environmental movement.’[10] Also emphasized is its ‘paired sense of loss and reclamation driving [an article entitled] ‘New Topographics Now’ as a utopic discourse. It does so by mourning the loss of familiar environments and envisioning other, often alien, models for dwelling and beauty in the landscape.’[11] Jenkins astutely acknowledged his interpretation as contingent – ‘for the time being.’ Whereas many of the images he selected, as strong works of art, have sustained attention and even gained emotional resonance as historical pictures of suburbia, in successive generations of viewers, for them/us Jenkins’ curatorial perspective is informative mainly as an example of a way of thinking of a particular time now past, and an analytic framework now less illuminating than confining.

Recent decades’ postmodern move away from demanding formal innovation and toward acceptance of politically inflected subject matter have allowed photographers’ more direct engagement with social problems such as humans’ destructive entanglements with natural systems. Even before the designation Anthropocene became known in the arts and humanities, several contemporary photographers gained recognition for their pictorial representations of humans’ gross negligence, outright destruction, and ecologically oblivious reconfigurations of natural terrains. In Seattle, the artist Chris Jordan enacts the construction of nature in his re-imaginations of familiar pictures. Jordan appropriated a famous image by Ansel Adams of the highest peak in North America, in Alaska, then named Mount McKinley. Originally and again recently it was titled ‘Denali’ by the local Native American tribe, meaning ‘the high one’. Jordan digitally reconstructed the image through an intricate grid repetition of the name plate DENALI from the sports utility vehicle of that name made by General Motors. (fig. 9) The number of rectangles comprising Jordan’s image, 24,000, represent six weeks’ of the Denali SUV’s global sales in 2006. The picture also functions as documentation of the artist’s research and visualization of data. In this focus on subject matter displaying the extent of humans’ mercantile presence in the environment, mixed into the grid, on half of the black ones, is another word, created by inverting the name’s last two letters: DENIAL. (fig. 10) Presumably, that refers to the gas-guzzling, carbon-emitting irresponsibility of driving a SUV, a practice prevalent among Americans. This image is part of his series Running the Numbers: An American Self-Portrait (2006-09) works imaging vast amounts of production, consumption, and waste, prompting awe over both the data and the clever manipulation of it. The rendering of such gargantuan extents could be characterized as a statistical sublime. A subsequent Running the Numbers series, subtitled Portraits of Global Mass Culture, includes a re-creation of Vincent van Gogh’s iconic painting Starry Night (1889) digitally fashioned from photographs of 50,000 cigarette lighters, representing the number of pieces of plastic floating in every square mile of the world’s oceans.

|

Fig. 9. Chris Jordan, Denali Denial, 2006. Archival inkjet print, 60 x 75 in. (152.4 x 190.5 cm). Courtesy of the artist. |

Showing large-scale evidence of human presence through picturing numerous instances of a thing is a manoeuver shared by many current photographers who merge landscape imagery and social-environmental concerns. The San Francisco Bay Area artist David Maisel makes photographs exclusively from the air. From there, a thick jumble of slender white rods looks like a box of dressmaker’s pins spilt on a black rug with a curving swath cut across it. In actuality it is a Maine forest of logged trees, denuded and in disarray around a river, about to travel downstream to become lumber. Maisel’s is an absolutely contemporary landscape image, of a biblical sign for knowledge and a historical icon of nature, the tree, becoming industrially processed. (fig. 11)

Maisel’s 2004 distant and deep aerial panoramas of many square miles of Los Angeles’ streets and structures can be viewed as an intensification of the suburban developments featured in the New Topographics. The intricate detail of grid and expansiveness emphasize topography. In a time when the practice of colour photography had become conventional, the choice of black-and-white applied to an aerial map-like format connotes documentary realism as it did to Jenkins. (fig. 12) Yet his streetscapes’ tonal reversal to the negative flattens the scene, spatially and emotionally, so that it fluctuates between something like cartography and intricate-realism-become-abstract-pattern, and between being super-real and fantastic. We see evidence of relentless, inexorable development, but at the same time the metallic ghostliness makes the terrain otherworldly, dreamlike. Poetically, Maisel entitled the series Oblivion, suggesting both the unconsciousness of sleep and of being oblivious to our environment and our effect on it. The formal manipulations exaggerate the documentary aspect into expressiveness, and the imagery, although photographically indexical, becomes an ominous foreboding. Both of these series are included in Maisel’s compilation of several years’ work entitled Black Maps, a self-canceling metaphor suggesting brooding, melancholy, and loss.

‘Spectacle’ is a customary strategy of photographers whose images highlight humans’ disproportionate presence in the ecological system. Peter Bialobrzeski, a German photographer and professor at Bremen’s University of the Arts, is particularly known for his exposure to Western viewers of southeast Asia’s megacities’ unruly growth. Densely sited skyscrapers are viewed at close range and in sparkling light, the lit interiors like a scattering of blindingly faceted diamonds, against which the ribbon of neon green dots call up a sign for trees but emphasize the simulated. (fig. 13) The critic Vicki Goldberg described that Bialobrzeski ‘achieves his unorthodox palette by going out in the late afternoon or early evening, most likely around seven, when the neon and fluorescent lights come on and mingle with the residual gleam of day. He has a four-by-five-inch view camera, a tripod and a large supply of patience. His exposures are long, from one-fifteenth of a second to four minutes. At these speeds, the film can’t register people rushing past; some disappear, others become transparent ghosts.’[12] For his album entitled The Raw and the Cooked (2011), Bialobrzeski adopted the famous differentiation that anthropologist Claude Levi-Strauss used in his 1964 book of the same title: the differentiation between things considered to be nature or natural – ‘raw’ – and those literally, structurally or mentally processed by humans into culture and beliefs – ‘cooked’. We can apply that on two levels to this picture – the aged blocky warehouse in the foreground is architecturally ‘raw’ in comparison to the dense stew of vertical grids peppered with glowing rectangles, but both are ‘cooked’ to variable extents in comparison to the confined ribbon of parkland between them.

Bialobrzeski’s book Nail Houses or the Destruction of Lower Shanghai (2014) documents a radical inversion of the neat tract homes pictured by the New Topographics. (fig. 14) The structures designated in China as ‘nail houses’ stick out because their residents refuse to leave to allow its demolition to make way for new construction. Builders have to elaborately construct around these dilapidated eyesores, but whose spontaneous vines provide the only experience of uncontrolled greenery in the chaotic over-built neighbourhood. This series documents both stifling corporate density and individual resilience in opposing homogenization with individualized squalor.

|

Fig. 14. Peter Bialobrzeski. Nail Houses, or the Destruction of Lower Shanghai, #0423, 2010. Courtesy of the artist. |

Art historian Greg Foster-Rice noted that ‘The [New Topographics] exhibition’s subtitle, ‘photographs of a man-altered landscape’, could almost have been recast as ‘photographs of a late-capitalist landscape’ for the way it describes the shift in the United States from industrial production to a more consumer-oriented society.’[13] In large-format albums such as Manufactured Landscapes (2003) and others, the Toronto photographer Edward Burtynsky has become well-known for an almost signature pictorial device of an extreme repetitive profusion – oil wells, parked automobiles, compacted cubes of metal refuse – illustrating the anthropogenic topic of the massive impact of industrial development on the natural environment. Burtynsky’s initial treatment of that in the 1990s was of quarries, such as massive extractions of granite by the Rock of Ages Corporation in Vermont, after which Burtynsky titled a series. (fig. 15) Using a large-format viewfinder camera for extremely crisp and detailed images, Burtynsky emphasizes numerousness, vastness, or gargantuan displacements – acts of destruction of natural matter for industrial production which have been termed images of a ‘dystopian sublime’.

The effect is both a mesmerizing visual spectacle and, like so many contemporary environmentalist landscapes, is ethically destabilizing: while aghast by the systematic flaying of a mountain, we admire granite counter tops and corporate lobbies’ gleaming floors. Burtynsky’s Rock of Ages series provides tangible evidence of the entwinement of fulfillment of consumer demands on an epic scale and ensuing resource depletion. And are these massive deep hole extractions as a biblical ‘Rock of Ages’ supposed to be taken as ironic, as after the rock is quarried the age of rock-in-situ ends? Saturated in colour and detail, his pictures are as rich as the consumerism that drives these extractions.

Burtynsky’s stacked cubes of ‘densified scrap metal’ in Ontario have the detailed intricacy of jewels or Kurt Schwitters’ recycling of detritus into striking assemblages. His pictures of an endless array of oil fields’ pumps, from his popular book Oil (2009), showing it from extraction to end products, have a bland journalistic straightforwardness that calls into question his attitude towards this industry. His photograph of vibrant tailing ponds – shallow pools of poisoned water runoff from mineral extraction, contained for evaporation, the metal oxidation of which often produces lurid hues – a subject common among aerial photographers of waste sites – present a forced geological eruption as a decadently gorgeous painterly abstraction. The photographic simulacra of the style – loose, flat forms, saturated hues, large print size and sensual expressiveness – of now prohibitively expensive Abstract Expressionist paintings conveys ambivalence about the pernicious practices which through their lens are made so visually compelling.

Artists’ formalization of overwhelming amounts of pre- or post-consumer goods materials as spectacular pictures of otherworldly landscapes may be a way of managing fears of looming catastrophes by bringing them under at least artistic control. The challenge of contemporary photography addressing our anthropocenic footprint is to not just overwhelm with the awesome imprint of our territorial aggression. As the eminent photography critic Max Kozloff has remarked: ‘Landscape photographers who want to make a statement about the deadening of the environment find that their own medium puts them into a quandary. They must steel themselves against ingratiation while somehow affirming the value of their abused subject.’[14]Burtynsky does this in one of his strongest images when he looks straight down the crevice pathway running between virtual mountains of charcoal hued automobile tire discards that extend beyond the frame, Oxford Tire Pile #8 (1999). (fig. 16) At the far end of the sheer cliffs of dark rings of rubber, a triangular patch of green against dirt and white sky cries out about consumption and the burden of garbage squeezing off free nature.

The density of signs of development in many of these contemporary images – a great intensification of those in the New Topographics – have allusions to the horrific that function ethically like the premonitory still life theme of vanitas or memento mori, distinguished by its scary skull.[15] As with that historical motif, the intention is to remind us of transience. Now, the moral is not to look beyond immediate wealth toward future heavenly redemption because our candle will be extinguished, our blossom wilt, our bubble burst, but to do so because the eroding environment itself has become a prominent conscious symbol that all things pass away, and with climate change, perhaps sooner than we expect.

A photographer explicit in her environmentalist advocacy is the Californian Camille Seaman, who makes that clear in the title of her first book Melting Away, A Ten-Year Journal Through our Endangered Polar Regions (2014). Breaching Iceberg (2008) mixes the grandeur of a mountain of ice, captured under overcast late afternoon conditions that produce the blue and turquoise hues, and evidence of its ‘breaching’, or melting and fracturing, due to the increase in global temperature of air and water. (fig. 17) Dramatic beauty and loss are entwined, as they are in her pictures of the isolation and scantiness of other icebergs, flattened into panels or irregular shards. Recognizing the oil consumption of those long distance flights to polar regions as contradicting her belief in the necessary to move away from fossil fuel consumption, Seaman turned to traveling the shorter distance to the western Mid-West to capture the freakish weather wrought by profligate carbon emissions.

Richard Misrach is the veteran photographer who in several series of works has merged political engagement – curiosity and advocacy – with grave acts of environmental degradation, with graceful formal restraint. In the late 1980s Misrach camped out in a Nevada desert where for 35 years the U.S. Navy took possession of public land and illegally tested high-explosive bombs. Those pictures (Bravo 20: The Bombing of the American West, 1990) show the festering wounds of bomb craters and animals killed by explosions and depleted soils. His Desert Cantos (1987) showed humans’ abuse of that southwest terrain. After Hurricane Katrina (2005), he went to New Orleans to photograph residential shambles and the howls of grief scrawled on exterior walls to governmental officials surveying the wreckage for potential razing. (Destroy this Memory, 2010)

Likewise, an exemplary act of attention by an artist to a deficient social/corporate/environmental relationship is Misrach’s boldly titled book Petrochemical America (2012), made in cooperation with architect and designer Kate Orff. Instigated by a 1998 commission by the High Museum, Atlanta, Misrach photographed a 150-mile industrial corridor along the Mississippi River east of New Orleans, and returned in 2010-11 to photograph sites again. The locale is the intersection of over 100 oil refineries, chemical manufacturing facilities, sugar refineries, arboreal landscapes and human habitats harmfully close in proximity. For its high incidence of sickness, this stretch of the Mississippi is known as ‘Cancer Alley’. There, 26,000 miles of pipeline penetrate the oil-laden southern parishes and across the coastal wetlands to make a web of canals cut through pastures and marshlands. With resulting erosions, wetlands are being ‘swallowed’ into the Gulf of Mexico, the salty tides seeping up into marshlands, withering trees. (figs. 2 and 18)

Misrach’s approach is also distinctive because the photographs are accompanied by the greater half of the volume being an Ecological Atlas by Orff. Imaginative charts and informative texts describe the network of petroleum, ecology, sociology and economics of the area, and by extension, of the developed world. The motivation is clearly educational, as a separate Glossary of Terms & Solutions for a Post-Petrochemical Culture slipped into a back cover pocket offers proactive solutions.

The ‘punctum’, as Roland Barthes would say, of Misrach’s Petrochemical America images is the tension between the dread that this malfeasance by transnational corporations is destroying life worldwide, and the luminous presence of his large prints. The subject matter of mercenary abuse of terrain and high incidence of disease among regional residents is ‘hot’ – socially, environmentally, politically – but astutely, akin to the sobriety characteristic of the New Topographics images, the moods – and hues – of Misrach’s images are emotionally reticent – ‘cool’. In both cases, it is a mistake to attribute that reserve to artistic ‘objectivity’ or detachment. Rather, the artists let us come to them, to behold the atmospheric pallor and staggering tree trunks, drunk on chemical efflux, to invest our empathetic engagement with terminal debilitation and, with the artists, to bear witness.

Reflecting on his subject matter in a roundtable discussion for the International Center of Photography’s 2006 exhibition Ecotopia, David Maisel remarked, ‘I don’t know that [it] has changed that much over time. But I do feel that the audience has changed. And their reception of the work has changed the most.’[16] Paralleling public recognition of climate change and of disproportionate human agency in relation to ecological systems, and with the lessening of both the modernist demand for formal and technical innovation and being disparaged for making ‘political statements’, ambitious artists no longer need to impersonally disguise and covertly whisper their engagement with environmental issues. Likewise, we can retrospectively recognize latent allusions in the New Topographics’ anthropogenic landscapes that have become overt in contemporary environmentalist photography.

CV

Suzaan Boettger is an art historian, critic and lecturer in New York City and Professor of the History of Art at Bergen Community College, New Jersey, where she teaches the history of photography. A scholar of earth, land, and environmental art, Dr. Boettger is the author of Earthworks: Art and the Landscape of the Sixties (University of California Press, 2003) and Nedko Solakov: Ninety-nine Fears (Phaidon, 2008). She has published numerous articles and exhibition- and book-reviews on painting, sculpture, and photography in periodicals spanning arts journalism and scholarly research and has contributed to twelve exhibition catalogues and books. In 2016, her survey ‘Within and Beyond the Art World: Environmentalist Criticism of Visual Art’ will be published in Handbook of Ecocriticism and Cultural Ecology (edited by Hubert Zapf and published in Germany by De Gruyter). Her book Climate Changed: Contemporary Environmentalist Art is in process. http://bergen.academia.edu/SuzaanBoettger ↑

NOTES

1. http://theredlist.com/media/database/photography/history/landscape-travel/ansel-adams/033-ansel-adams-theredlist.jpg (accessed 1 December 2015). ↑

2. Baltz himself enacted several times this frontal pose yet expressive refusal when being photographed for a portrait by choosing to wear large dark glasses. https://www.google.com/search?q=lewis+baltz+portrait&oq=lewis+baltz+portrait&aqs=chrome..69i57.7927j0j4&sourceid=chrome&es_sm=0&ie=UTF-8 (accessed 1 December 2015). ↑

3. This article is based on a talk for the symposium ‘From a ‘Topographic’ to an ‘Environmental’ Understanding of Space—Looking into the Past and into the Presence of the New Topographics Movement’ at the Museum für Photographie, Brunswick, Germany on 30 October 2015, in conjunction with the exhibition Landschaft. Umwelt. Kultur. On the New Topographics’ Transnational Impact. With appreciation to Dr. Gisela Parak, Director, for the invitation to participate. ↑

4. Jenkins 1975, p. 5.↑

5. Jenkins 1975, p. 7. ↑

6. http://www.geh.org/ne/str085/htmlsrc9/m198111310014_ful.html (accessed 1 December 2015). http://www.moma.org/collection/works/80143?locale=en (accessed 1 December 2015). ↑

These two really need to be viewed side-by-side to note their remarkable similarities of form and mood, as do the other pairs mentioned, but constraints on reproduction rights by some artist’s estates make that adjacent placement impossible. ↑

7. Pincus-Witten 1977, p. 19.↑

8. Mitchell 2002, p. 20.↑

9. Morton 2007, p. 1. ↑

10. Foster-Rice 2013, p. 53. ↑

11. Burnett 2013, p. 151.↑

12. Goldberg 2004.↑

13. Foster-Rice 2013, p. 50.↑

15. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/works-of-art/1974.1 (accessed 15 October 2015). ↑

16. International Center of Photography 2006, p. 23.↑

References

Ansel Adams and Nancy Newhall 1960, This is the American Earth. San Francisco: The Sierra Club.

Christopher Burnett 2013, ‘New Topographics Now: Simulated Landscape and Degraded Utopia’, in: Greg Foster-Rice and John Rohrbach (eds.), Reframing the New Topographics, Chicago: The Center for American Places at Columbia College Chicago.

Finis Dunaway 2005, Natural Visions: The Power of Images in American Environmental Reform, Chicago: University of Chicago.

Greg Foster-Rice 2013, ‘Systems Everywhere. New Topographics and Art of the 1970s’, in: Greg Foster-Rice and John Rohrbach (eds.), Reframing the New Topographics, Chicago: The Center for American Places at Columbia College Chicago.

Vicki Goldberg, ‘The Emerald Megacities of Southeast Asia’, New York Times, 11 April 2004. http://www.nytimes.com/2004/04/11/arts/art-the-emerald-megacities-of-southeast-asia.html (accessed 15 October 2015)

International Center of Photography 2006, ‘Ecotopia. A Virtual Roundtable’, in: Ecotopia, exh. cat. New York: International Center of Photography, p. 23.

William Jenkins 1975, New Topographics: Photographs of Man-Altered Landscapes, exh. cat. Rochester, N.Y.: George Eastman House.

Max Kozloff, ‘Ghastly News from Epic Landscapes’, American Art, 5 (Winter/Spring 1991) 102, p. 119.

Bruno Latour 2004, Politics of Nature. How to Bring the Sciences into Democracy, Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

W.J.T. Mitchell 2002, Landscape and Power (second edition). Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press.

Timothy Morton 2007, Ecology Without Nature, Rethinking Environmental Aesthetics, Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Robert Pincus-Witten 1977, ‘The Seventies’, in: A View of a Decade, exh. cat. Chicago: Museum of Contemporary Art.

Eliot Porter 1962, In Wildness is the Preservation of the World. San Francisco: The Sierra Club.