From ‘Topographic’ to ‘Environmental’ – A Look into the Past and the Presence of the New Topographics Movement

Abstract

Forty years after its inauguration, the 1975 George Eastman House exhibition New Topographics – Photographs of a Man-Altered landscape is generally considered as legendary. Moreover, one talks of a New Topographics movement. How did the show become the myth it is today? Who are the protagonists that keep this movement alive? This essay argues the New Topographics’ legacy and claims that next to the style that curator William Jenkins has identified as ‘topographic’ to summarize the photographers of the New Topographics exibition , it was the topic of a ‘man-altered landscape’ that resonated in all other parts of the world. Based on the exhibition Landschaft. Umwelt. Kultur. On the New Topographics’ Transnational Impact and a symposium held on 30 October 2015 at the Museum für Photographie in Brunswick, Germany,[1] this essay explores how the ideas of the New Topographics disseminated transnationally and merged with the emerging environmental conscience at the end of the 1970s. Furthermore, parallel or roughly at the same time, a flourishing of photographic methods of presenting landscape and nature in a more timely matter originated in Germany, France, and in the Netherlands. This essay suggests that after forty years of critical landscape depiction, the ‘topographic’ approach was dissolved by an ‘environmental’ understanding of landscape representation.

Article

Sometimes ideas appear to hang in the air. One talks today of the exhibition New Topographics – Photographs of a Man-Altered Landscape, which curator William Jenkins presented at the George Eastman House in Rochester in 1975, as shaping and inspiring a complete generation of photographers. In this exhibition the photographers who had been put together by Jenkins dealt with the change in American suburbs and the phenomenon of newly built tract house estates. With a style whose drily objective and almost clinically cold observing character was emphasized by Jenkins,[2] the photographers discovered not only the urban sprawl as a subject of photographic debate but also its effects on the adjacent environment.

Today the photographs of the New Topographics, whose critical potential developed from their quality as artistic documentary testimonies to the architectural and urban development changes to the country and from the aesthetic value of their photographs, are now associated with the emergent environmental consciousness of the 1970s.[3] The works of the New Topographics illustrate here the intrusion into the ecological balance by the development of the landscape and the resulting shift of the boundary between ‘culture’ and ‘nature’ in the tradition of Walker Evans’ documentary style.[4] Embedded in contemporary debates, like the discussion of environmental pollution caused by urban sprawl,[5] the New Topographics exhibition can thus be understood as a catalyst of a transnational movement. However, this point of view gives the impression at the same time that the New Topographics – from Rochester – had influenced, or perhaps even renewed the photographic direction of the European countries with their environmentally concerned perspective.

In contrast to this generalizing assumption, a very different genesis of critical photographic landscape depiction can be posited, namely that the alliance between photography and environmental awareness evolved in the sense of a history of ideas. According to this, the ‘topographical’ perspective developed in centers that were independent of each other with various time-lags between them, and was shaped by different players; the individuals often only knew by hearsay of their American ‘precursors’. However, the enormous interest in the changes to ‘man-made landscapes’ initiated over forty years ago a photographic thematic area, which has continued to grow till the present day. Since the seventies in France, Germany and the Netherlands, the ‘topographical’ registry, interpretation of, and investigation into ‘landscape’ and ‘environment’ have constituted an important subject of photographic debate. Nonetheless, the photographic accentuations show individual points of focus and national differences and lean on differing photographic traditions as well as on cultural ways of looking at things. Thus, it can be established that a lively exchange had developed on associated themes within the discourse on photography, well before Paul J. Crützen’s definition of the ‘Anthropocene’ as the epoch created by humans was taken up in an almost inflationary manner by the German media and scholars.[6]

Eco-images as Political Agitation

Images are defined as ‘eco-images’ when they are specifically used within the framework of a political campaign and are intended to shake up the general public and appeal to the latter’s ecological conscience.[7] There were numerous examples of such eco-images in the emerging environmental movement of the sixties and seventies but these circulated mainly outside the discourse of artistic photography and the official art scene, such as the Land Art movement and photoconceptual work of the 1960s.[8] In reference to this, the example that was most discussed in detail is the series of illustrated books presented by the Sierra Club with its prominent photographers Ansel Adams, Eliot Porter, and Charles Pratt.[9]

However, there were and are, time and time again, always interesting overlaps in areas with artistic, photojournalistic or activist photographic focus. W. Eugene Smith’s series Minamata (1971-75), first published in book form in 1975, about the consequential damage of mercury poisoning to a Japanese fishing village, is one of the first visual interpretations of the issue in the medium of journalistic pictorial report. The book illustrates in dismal but memorable images the human suffering of the village and shows the physical deformations of those affected in dramatic pictures. Secondly, the pictorial program Documerica, which was associated with the American Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) from 1971 to 1977, offers an early example of photographic imagery to raise environmental conscience. Following the successful RA/FSA Photography of the 1930s, Documerica was intended to publicize the newly introduced environmental protection measures for the American public and encouraged the media to disseminate its images. A show entitled Our Only World originated from the program that was inaugurated at the Smithsonian Institution in 1974, but also sent to the 1976 World Environment Exhibition in Tokyo to promote the role of American environmental policy as a forerunner of and role model for international action.[10] Although the impression of a pedagogical, educational intention dominates within the overall orientation of Documerica commissions, the program also produced countless artistic photographs of a high quality, which developed from the photographers’ own investigations. (figs. 1 and 2)

First Self-commissioned Artistic Representations

In an early stage of his career the American photographer Richard Misrach began to deal with aspects of environmental protection problems in his work. His series Desert Cantos, published in 1987, takes up the traditions of American vernacular landscape photography as a landscape coined by the infrastructure of modern life in the 1930s.[11] Misrach shows minor disorders in the endless expanse of landscape panoramas, which contradict the impression of a natural idyll, such as remnants of military explosive tests. It became typical for the photographer to investigate his case studies over a long period of time and to examine the history of places and areas whose fate he than makes possible for the observer to experience. Misrach’s volume Bravo 20, The Bombing of the American West, published in 1990, relates the history of the secret bomb tests of the U.S. American marines in the Nevada Desert, which caused a moon crater landscape. The photobook Petrochemical America (2014) in contrast, presents the long-term damage of the oil-processing industry in the so-called Cancer Alley along the Mississippi River. In his series Desert Cantos, Misrach for the first time connected artistic photography and a photographic portrayal of the long-term effects of mercury poisoning in a way that was both, strongly political but also aesthetic.

The difference between artistic and political motivation, on the other hand, was made clear by two works from the early 1980s by Lewis Baltz and John Gossage, which were published almost ten years after the New Topographics exhibition. While Baltz was presented by William Jenkins as part of the New Topographics in 1975, his friend Gossage was not represented in the show. In this context, Gerry Badger has characterized the artistic exchange between Lewis Baltz, John Gossage, William Eggleston, and Michael Schmidt at the Werkstatt für Photographie (Workshop for Photography ) in Kreuzberg in the early 1980s as crucially important for the photographers’ careers.[12] In 1985 Gossage published his photobook The Pond, in 1986 Baltz his San Quentin Point. Before those book publications, both series had been exclusively presented in the photographic journal Camera Austria.[13] In Camera Austria volume 11/12 of 1983, Baltz explains his understanding of artistic documentary photography and verifies that no ecological intention preceded his series Park City or San Quentin Point. Nevertheless, the series’ critical message is evident. In Baltz’s words, Park City is a photobook about the spectacle of the creative and destructive forces of capitalism, whereas San Quentin Point describes a dead, forlorn and futureless place: ‘San Quentin Point is world in decline, in decay: form degenerates into a chaotic parody of itself and all meaning, all significance is lost. It is a place where human work, nature and culture melt together in an entropic way.’[14] For Baltz, the description of the place formulates its own criticism which makes a further political agitation superfluous:

‘I hope that I have let the place speak for itself in my pictures, for what can be criticized about Park City seems obvious enough to me and that no further interference or embellishment on the part of the photographer is necessary. I hope you have only seen what is there and not the coarse attempt to propagate my own opinion. If this is not the case, then I see this as a problem – as an error in my work.’[15]

Thematically, San Quentin Point carries out a radical shift of photographic landscape representations. (fig. 3) The finely differentiated black-and-white images show sections of bleak peripheral zones and undergrowth, in which only remnants of desolate nature next to garbage can be seen. The branches seem to be characterized by their irreversible destruction. The sectional character of the scenarios dissolves the landscape panorama; fragmented single areas stand by themselves and no longer belong to a larger unified whole or nature space. Also Gossage’s The Pond can be compared to a forensic search for traces of human-made devastation of nature. (fig. 4) On the edge of a town settlement Gossage tracks down points in which nature has up to now been left to its own devices, but is in danger in the next moment of being destroyed by areas of building: ‘to be swallowed up by suburbia.’[16] In his photographic forays through the town periphery Gossage refers to the American transcendentalist Henry Thoreau and his seminal writing Walden of 1854. A photographically localized, yet fictitious place remains nebulous despite the naturalistic portrayal. While nature, celebrated by Thoreau as being untouched – actually Walden’s Pond was situated very near to a well-developed railway line – is transfigured into a spiritual place of retreat, well removed from all civilized evil, Gossage’s photographs show places in which scarcely anything idyllic and unadulterated is conserved. In spite of all this, they radiate a tranquility, which might be described as being the final deep breath before the ultimate loss of the place.

Fig. 3 Lewis Baltz, San Quentin Point, no. 40, 1983. © mc.galerie@free.fr

Fig. 4 John Gossage, The Pond, 1985/86.© permissions@fraenkelgallery.com

The conceptual understanding of photographic representation – with the works of Baltz and Gossage leading the way here – can also be related to Robert Smithson’s famous essay A Tour to the Monuments of Passaic, New Jersey (1967).[17] Smithson showed the devastations of industrial and settlement history as being modern monuments. Combining text and photographs, Smithson turns his writing into a conceptual artwork. Just like this piece of intellectual reflection of the function and possibilities of photographic depiction, San Quentin Point and The Pond do not portray any photographic documentation of the place, but carry out a reflection on the meaning of visual representation of the place at the interface of Land Art, conceptual art and artistic photography. As outlined, its primary direction of thrust was not a politically adopted ecological goal. However, Baltz and Gossage were well aware of the environmental message spread by the images. Moreover, the notion of ‘entropy’ – to be understood as the distraction of energy and degradation of a site – was given prominent importance. Not only did Baltz use it in his 1983 article as cited above, but Smithson also defined the wasteland as a place where energy has been removed.[18] It can therefore be ascertained that the label ‘New Topographics’ neglected the immanent references to the environment made by the photographers.

Cultural Criticism in the Genre of Landscape Photography

Parallel to the American photographers, the photographers in the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) in the 1970s discovered ecological themes for their art.[19] Yet the New Topographics exhibition was only known by hearsay to the students of the Folkwang School in Essen at the end of the 1970s.[20] Nevertheless, in the West German photo scene a comparative change in the perception and view of nature and landscape took place. In the USA the discussion about the vernacular landscape and the reshaping of landscape through everyday culture provided fertile ground for public discussions. In particular, the interested public was made aware by J.B. Jackson’s journal Landscape since 1951 and by the two architects Robert Venturi and Denise Scott Brown who published their influential Learning from Las Vegas in 1972. For the photographers of the FRG, on the other hand, the legacy of the Ruhr Area photography and the cultural criticism of the Frankfurt School constituted important points of reference.

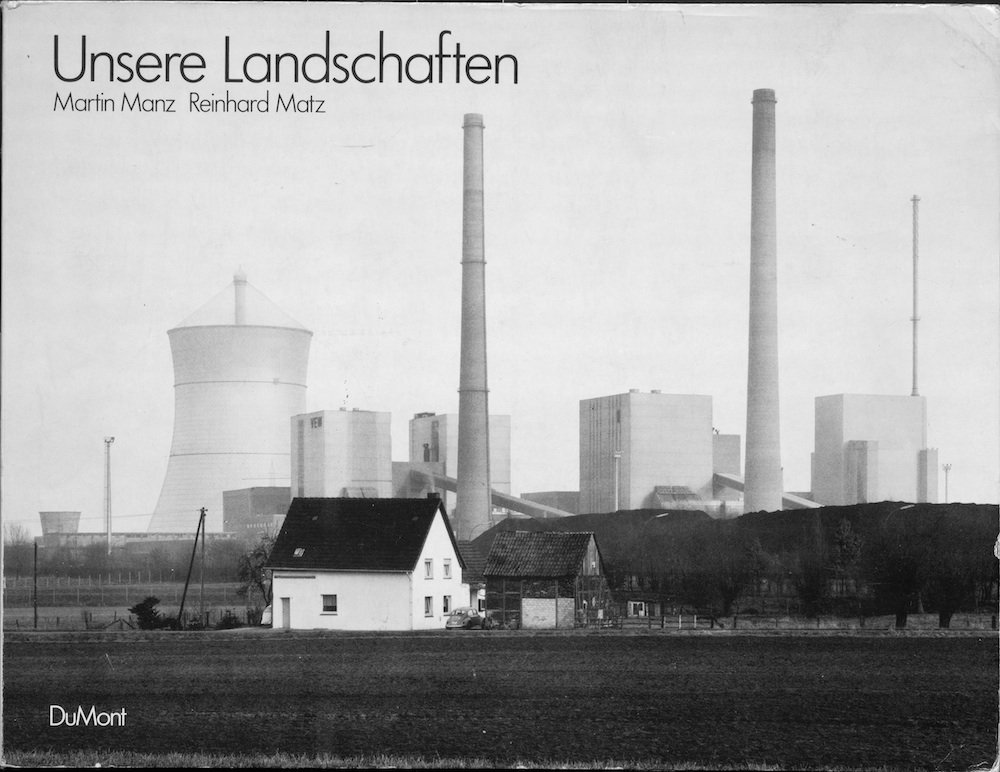

The substantial photo book Unsere Landschaften (Our Landscapes), published by Martin Manz and Reinhard Matz in 1980, is one of the key publications of this time. (fig. 5) In this book both photographers present a thoroughly critical depiction of the structural transformation of the towns, a criticism of the urban development model of the car-friendly town in post-war Germany, just as the cultural critic Alexander Mitscherlich had done in Die Unwirtlichkeit unserer Städte (The Inhospitality of our Towns) in 1965.[21] In sinister black-and-white photographs Manz and Matz draw an extremely gloomy picture of the town, which is affected by massive concrete buildings and inner-city ring freeways. The photobook uses political motivation, quotes left-wing intellectuals such as Italo Calvino, Bertold Brecht and Karl Marx, and refers to a political understanding of art as a medium of sharing, exchange of opinions and activation of the responsible citizen. The photographic descriptions of the current situation that are dealt with here are transferred into statements with a very clear political direction. They are not to be understood, as is the case of Lewis Baltz, as purely visual, aesthetic statements.

Heinrich Riebesehl’s Agrarlandschaften (1979) with its succinct depiction of the industrialization of agriculture and the structural transformation of village life can be regarded as the second decisive publication of the time. (fig. 6) Extensive monocultures and farmed areas, torn-up arable land and leveled fields show here how modern agriculture subjugates nature to the idea of profit yielding and time-saving. Riebesehl concentrates his statement, however, on the area of the aesthetic, i.e. he lets his pictures speak for themselves, like Baltz did. In the Workshop for Photography yet another representation of nature was developed. In the photographic series by the two lecturers of the workshop, Michael Schmidt and Ulrich Görlich, the wild bushes of town wastelands served as a metaphor for the changes in the relationship between people and nature. (fig. 7) Similar series were produced by the students of the workshop, for example by Ursula Wüst and Friedhelm Denkeler.[22] Independent of the Workshop for Photography, the photojournalist Wilfried Bauer developed a concept of resistant nature which reconquers the cities’ marginal sites, in his series Stadtbäume (City Trees, 1978-82). (fig. 8)

|

Fig. 7 Ulrich Görlich, [Untitled], 1978, published in: Honnef, Klaus (ed.), In Deutschland, Bonn 1979. © Ulrich Görlich / VG Bild-Kunst Bonn 2015 |

|

Fig. 8 Wilfried Bauer, Berlin-Tiergarten, Europachter, 1979, from the series Stadtbäume, 1978-1982. © Stiftung F.C. Gundlach |

At the most important West German photographic training center of the time, the Folkwang School in Essen, other topics were the focus of interest, like the use of colour or the changes in photojournalism. Otto Steinert’s model of a photography inspired by the artistic creative force of the photographers was in fact being slowly replaced by a new interest in all forms of the documentary.[23] Nevertheless, together with the newly vitalized, artistically expanded concept of the documentary, the interest in the irreversible transformation of the Ruhr Area also flourished. Not only the conceptual approach of Bernd and Hilla Becher perpetuated the industrial monuments, which were in a state of decay with its photographic typologies, but also the long-term observations of Joachim Schumacher who began his documentation of the transformation of the Ruhr Area in the mid-seventies. (figs. 9 and 10) The notion of the maintaining and preserving adherence to historical substance in the medium of photography was absolutely central to his inventory of the landscape. More recent positions like those of the German photographer Bettina Steinacker continue this debate today and show new aspects of the transformation of the Ruhr Area and its natural landscapes, which took leave of its coal and steel industry as well as other heavy industries long ago.

Similarities and Differences between the French and Dutch Landscape Perception on the one hand and the New Topographics on the other hand

In an age of globally blossoming environmental awareness, the resonance of the pressing topic can also be found in photography. In the early 1980s, the French Government also felt encouraged to commission a similar venture because of the American state-sponsored photography programs and the New Topographics exhibition.[24] In 1983 the planning office DATAR (La Délégation Interministérielle à l’Aménagement du Territoire et à l’Attractivité Régionale) launched the Mission Photographique de la DATAR, which during its runtime of six years commissioned 29 photographers with producing artistic perceptions of the landscape and the structural transformation of rural France. One reason for the granting of the state commission is the thought about historic preservation and the documentation of cultural assets, having the same purpose as the Mission Héliographique already had in 1851. In contrast to a strictly topographical survey, as William Jenkins’ conceptual framework had provided for – and the adoption of a collective movement with a shared uniform style – the artistic expression and artistic interpretation of the landscape was at the forefront of the Mission Photographique de la DATAR from the very beginning. The commissioned photographers thus display a style that was very much their own and was not identical with the catchword of the ‘topographic’. Raymond Depardon’s series La Ferme du Garet, Dans la Plaine de Mâcon, which he later continued in his series La France, shows photographs of the disappearing rural France in the tradition of the Picturesque, but also caustic superimpositions of old and new in the views of towns. The photographer Jean-Louis Garnell, who was still very young at the time of the commission, translated the stylistics of the New Topographics into the French context. With his very successful visual compositions and pithy comments, his series Chantiers, Paysages en Transformation opens a dialogue with American landscape photography. Garnell creates diptychs to point out contrasting conditions of specific sites, encouraging the viewer to think about the concept of contemporary landscapes. (figs. 11 and 12) In the photographic series Tableaux (1978-82) by the painter Jean-Marc Bustamante, the compositional criteria of painting are of central importance. His landscape impressions, presented as large-format tableaux, reflect on transitions and forgotten places of urban peripheries. However, Bustamante’s artwork, that was not commissioned by any governmental agency, is closer to the non-agitated, neutralizing compositions of the New Topographics than many a photograph of the Mission Photographique de la DATAR.

|

Fig. 11 Jean-Louis Garnell, Paysages 21, 1986. © Jean-Louis Garnell /ADAGP / VG Bild-Kunst Bonn 2015 |

|

Fig. 12 Jean-Louis Garnell, Paysages 25, 1986. © Jean-Louis Garnell /ADAGP / VG Bild-Kunst Bonn 2015 |

Dutch landscape photography looks back on its very own tradition of painterly representation of nature and discovered the theme of environmental protection in the 1980s. Curator of photography Frits Gierstberg (Nederlands Fotomuseum, Rotterdam) attributes the decisive influence on the development of a generation of younger Dutch photographers like Cary Markerink, Theo Baart, and Jannes Linders to the New Topographics.[25] But the exhibition New Topographics, which after its start in Rochester was shown in some European countries in a reduced form, was not shown in the Netherlands until 2011. Not only the main subject Wasteland,[26] which was thematically realized within the framework of the Third Photography Biennale in Rotterdam in 1992, but also a number of state commissions helped to promote the further developments and refinement of environmentally related photographic approaches.[27] In the Dutch conception of nature the understanding of a ‘malleable land’ is characteristic, i.e. the land is understood as being malleable, can and may be reshaped, adopted and reworked by humans according to their needs.[28] It may be because of this concept that the Dutch photographic landscape depictions are characterized by a subtle irony and illustrate an uninhibited perception of landscape. There is no sign of a comprehensive criticism of civilization, no fear of the end of humanity, as is latently present in the depressing landscape images of German origin. Instead, you can recognize something like delight in the view of the photographers regarding the hybrid forms of cultured nature and contemporary ambiguities. Hans Aarsman’s Hollandse Taferelen (Dutch scenes, 1989) describes the state of the country and at the same time shows the comic – sometimes even tragicomic – aspects of these human superstructures in a masterly way. His photographs create the impression of a theatrical landscape in which even the cows adjust to the aesthetic guidelines of the humans in a perfect dramatic composition. This sophisticated dealing with the artificial forms of nature can be found in numerous works of Dutch photographers and video artists.[29] In contrast, the individual projects of Theo Baart look almost classically ‘topographic’, like his series Bouwlust, The Urbanization of a Polder (published in 1999), which records in detail how the formally rural countryside of the Amsterdam Schiphol Airport area has changed over the last decades. Where once ‘old’ farmhouses stood, ultramodern functional apartments and houses are spreading now. One seminal contradiction remains: these new urban districts have not dissolved the original landscape, as the polder land was artificial from its very beginning as reclaimed land. The issue of chemically contaminated places whose idyllic impression is deceptive has, on the other hand, been brought to the attention of the public by Wout Berger’s photobook Poisoned Landscape (published in 1992), analogous to his American colleague, Richard Misrach.

From ‘Topography’ to ‘Environment’

In the past forty years topographical landscape representations have perpetuated themselves to such an extent that speaking of a transnational ‘movement’ seems to be justified. The New Topographics exhibition of 1975 can be seen here as an important impulse. It is, however, wrong to represent it as the only initiator and start of comparable photographic approaches in western countries. Autonomous developments within the European photo scene have equally contributed with individual approaches and themes. The photography of the Federal Republic of Germany, the Mission Photographique de la DATAR in France right up to the intensive occupation of Dutch photographers in the nineties with related themes – in all these we can observe a change in the language of narrative. With the exhibitions Imaging a Shattering Earth: Contemporary Photography and the Environmental Debate (Meadow Brook Art Gallery, Oakland University, Rochester, Michigan, 2005) and Ecotopia (The Second ICP Triennial of Photography and Video, International Center of Photography, New York City, 2006) the designation of ‘environmental photography’ began to slowly replace the accentuation of the ‘topographic’.[30] So we can summarize that photographic practice has kept alive the occupation with the continuous change in the human-nature dichotomy for forty years. In addition, the photographic accentuations reflected the respective themes of their time and have made the shifting of focal points visible. The 2015 exhibition Landschaft. Umwelt. Kultur at the Museum für Photographie in Brunswick, Germany has shown some of these references and the photographic reactions to these historical debates. It consciously adapted the New Topographics exhibition’s subtitle of a ‘man-made landscape’, to point out that the influence of humans on the Earth, but also its discussion, has become even more severe and visible than in the 1970s. Since 1974, the general discussions of the boundary, shifting with the growth of suburbia, between town and countryside, the arising peripheral structures and the concentration of urban development, have all sensitized the population to the destruction of the environment.

Besides setting out a collection of historical case studies, the exhibition sought to argue more contemporary ways to explore topographic landscape matters. What ways of depiction of ‘nature’ and ‘landscape’ seem to actually correspond to our time in view of human intervention in the ecological balance? What notion of ‘nature’ can we still have in the age of climate change, in an era which is characterized by the loss of the diversity of species and the gradual uninhabitability of the Earth? What can still be considered as a contemporary, and critical representation of the ‘landscape’ in 2015? Looking back at the history of the New Topographics is at the same time looking at the future. Photographers of the present time are characterized by a strong interest in the periphery, the wastelands and unoccupied or wild niches of urban fringes. In her series Wasteland Ecology, Jennifer Colten investigates man-made edgelands as marginal, forgotten sites at the edge of civilization and the biodiversity, which has developed in these peripheral areas. It almost seems as if something like a natural space, autonomous from humans, has reconquered these shattered places. (fig. 13) Christina Capetillo’s photographs of the landscape, on the other hand, resemble scientific, technological typologies and are at the same time of captivating beauty. Flooded fields, edge strips or plants that have colonized the middle strips of the highways, have no practical use for people, but a space of contemplation is opened up by the graphic tenderness of the compositions. In turn, Carma Casulá and Rachael Jablo make the dichotomy of humans and nature a subject of discussion in a very humorous way. Jablo’s series Neighbors (2014) is devoted to the mute rivalry of neighbors which is carried out via the visibly effective greening of the living space and the ways in which green plants as a socio-biotope embody the standard of living of their owners. In Casulá’s series Al natural (2014), the humans adapt themselves and their leisure behavior to the changed circumstances, occupy and investigate the transformed cultural landscape in swarms in order to enjoy, above all, an unblemished ‘nature adventure’. Thus the Spanish photographer shows the complex reality of different types of landscapes formed by humans. (fig. 14) The New Topographics movement contributed considerably to establishing critical environmental representations in the canon of artistic photography. With countless themes and forms of representation of environmentally critical aspects, a complex and diverse discussion of the relevant issues has developed, which has been introduced and put into context by the exhibition Landschaft. Umwelt. Kultur.

CV

Gisela Parak (PD Dr.) is the director of the Brunswick Museum for Photography, Germany, and teaches at the Brunswick Technical University. She was a postdoctoral fellow at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, at Washington University, St. Louis, and at the German Historical Institute in Washington, D.C. Her work focuses on the history and theory of photography, American cultural history and art history of the 19th and 20th century.↑

NOTES

1. The exhibition Landschaft. Umwelt. Kultur. On the New Topographics’ Transnational Impact was on display at the Museum für Photographie in Brunswick,Germany, from October 23 to November 29, 2015, and was curated by the author of this article.↑

2. Jenkins 1975, n.p. ↑

3. Dunaway 2010, p. 14. ↑

4. Green 1984, p. 163.↑

5. Parak 2014, p. 334.↑

6. Schwägerl 2012. ↑

7. Parak 2013, p. 5. ↑

8. Dunaway 2015.↑

9. Dunaway 2005; Kelsey 2013; Solnit 2009.↑

10. Parak 2013.↑

11. The term ‘vernacular landscape’ usually refers to Walker Evans’ depiction of modern life in the 1930s and the spread of gasoline stations, telegraph post etc. to inhabit the countryside, and was prominently discussed by J. B. Jackson. See Jackson 1984. ↑

12. Badger 2010, n.p. ↑

13. Baltz 1983; Gossage 1985/86.↑

14. Baltz 1983, p. 6.↑

15. Baltz 1983, p. 13.↑

16. Badger 2010, n.p. ↑

17. Originally published as ‘The Monuments of Passaic’, Artforum, December 1967.↑

18. Smithson 1996.↑

19. In the German context the two most well-known artistic actions in the area of fine arts were Joseph Beuys’ Stadtverwaldung on the occasion of Documenta 7 (1982), and Klaus Staeck’s Staecks Umwelt. Texte und politische Plakate (1984).↑

20. Discussion with Joachim Schumacher on 24 July 2015 in Brunswick, Germany. In this context, it would also be logical to discuss the New Topographics’ impact via Bernd and Hilla Becher on their students. However, at least to the knowledge of the author, there has not been any scholarly discussion of the New Topographics’ direct impact on the Düsseldorf Photo School so far. Bernd and Hilla Becher started teaching at Düsseldorf Academy of Fine Arts in 1976. Christof Schaden has elaborated on the American-German exchange that the Bechers established and that was important for the work of Elger Esser, Andreas Gursky, Candida Höfer, Axel Hütte, Simone Nieweg, Thomas Ruff, Jörg Sasse and Thomas Struth. Schaden refers to the work of Stephen Shore as being of specific importance though and was criticized for this confinement. See Gronert 2011. However, in general art historians have argued a much wider field of photographic influences as being of importance for the Düsseldorf Photo School, such as conceptual art and minimal art. See Lippert and Schaden 2010. ↑

21. Manz and Matz 1980.↑

22. Werkstatt für Photographie 1980.↑

23. Parak 2015a.↑

24. Bertho 2013, p. 69. ↑

25. Gierstberg and De Ruiter 2007, p. 223. ↑

26. Gierstberg and Vroege 1992.↑

27. Gierstberg 1998.↑

28. Gierstberg and De Ruiter 2007, p. 192.↑

29. Van den Heuvel and Metz 2008.↑

30. Parak 2015b, p. 12.↑

References

Badger, Gerry 2010, ‘Genesis of a Photobook’, in: Gossage, John (ed.), The Pond, New York: Aperture.

Baltz, Lewis 1983, [Interview], Camera Austria no. 11/12 (combined issue).

Bertho, Raphaële 2013, La Mission Photographique de la DATAR. Un Laboratoire du Paysage Contemporain, Paris: La Documentation française.

Braddock, Alan C. and Irmscher, Christoph 2009 (eds.), A Keener Perception. Ecocritical Studies in American Art History, Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press.

Dunaway, Finis 2005, Natural Visions. The Power of Images in American Environmental Reform, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Dunaway, Finis 2010, ‘Beyond Wilderness. Robert Adams, New Topographics, and the Aesthetics of Ecological Citizenship’, in: Foster-Rice, Greg and Rohrbach, John (eds.), Reframing the New Topographics, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Dunaway, Finis 2015, Seeing Green. The Use and Abuse of American Environmental Images, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Foster-Rice, Greg and Rohrbach, John 2010 (eds.), Reframing the New Topographics, Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Gierstberg, Frits 1998 (ed.), Suburban Options. Photography Commissions and the Urbanization of the Landscape, Rotterdam: Nederlands Foto Instituut.

Gierstberg, Frits and Vroege, Bas 1992 (eds.), Wasteland. Landscape from Now On, Rotterdam: Nederlands Foto Instituut.

Gierstberg, Frits and De Ruiter, Tineke 2007, ‘The Metamorphosis of a Malleable Land’, in: Flip Bool et al., Dutch Eyes. A Critical History of Photography in the Netherlands, Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz.

Green, Jonathan 1984, American Photography – A Critical History 1945 to the Present, New York: Abrams.

Gossage, John 1985/86, [Artist statement], Camera Austria no. 19/20 (combined issue).

Gronert, Stefan, Review of: Lippert, Werner and Schaden, Christoph 2010 (eds.), Der rote Bulli. Stephen Shore und die Neue Düsseldorfer Fotografie. Exh. cat. NRW-Forum Düsseldorf, 2010, Sehepunkte, 11 (2011) 1 [15-01-2011]. http://www.sehepunkte.de/2011/01/19064.html (accessed 16 November 2015)

Jackson, J.B. 1984, Discovering the Vernacular Landscape, New Haven: Yale University Press.

Jenkins, William 1975 (ed.), New Topographics. Photographs of a Man-altered Landscape, Rochester: George Eastman House.

Kelsey, Robin 2013, ‘Sierra Club Photography and the Exclusive Property of Vision’, in: Parak, Gisela 2013 (ed.), Eco-Images: Historical Views and Political Strategies, RCC Perspectives no.1.

Lippert, Werner and Schaden, Christoph 2010 (eds.), Der rote Bulli. Stephen Shore und die Neue Düsseldorfer Fotografie, exh. cat. NRW-Forum Düsseldorf.

Manz, Martin and Matz, Reinhard 1980, Unsere Landschaften, Cologne: DuMont.

Parak, Gisela 2013 (ed.), Eco-Images: Historical Views and Political Strategies, RCC Perspectives no.1.

Parak, Gisela 2014, ‘Picturing the State of the Nation’s Environment: Early Aerial Photography in the United States from the 1930s to the late 1960s’, in: Schneider, Birgit and Nocke, Thomas (eds.), Image Politics of Climate Change. Visualizations, Imaginations, Documentations, Bielefeld: Transcript.

Parak, Gisela 2015a, ‘Ein anderer Blick. Über die westdeutsche (Autoren-)Fotografie der 1970er und 1980er Jahre’, in: Parak, Gisela (ed.), Die wilde Vielfalt, Fotogeschichte no. 137.

Parak, Gisela 2015b, Photographs of Environmental Phenomena. Scientific Images in the Wake of Environmental Awareness, USA 1860s-1970s, Bielefeld: Transcript.

Schneider, Birgit and Nocke, Thomas 2014 (eds.), Image Politics of Climate Change. Visualizations, Imaginations, Documentations, Bielefeld: Transcript.

Schwägerl, Christian 2012, Menschenzeit: Zerstören oder gestalten? Wie wir heute die Welt von morgen erschaffen, Munich: Goldmann Verlag.

Smithson, Robert 1996, ‘Entropy Made Visible’ (1973), in: Flam, Jack, (ed.), Robert Smithson: The Collected Writings, Berkeley: University of California Press.

Solnit, Rebecca 2009, ‘“Every Corner is Alive”: Eliot Porter as An Environmentalist and Artist’, in: Braddock, Alan C. and Irmscher, Christoph (eds.), A Keener Perception. Ecocritical Studies in American Art History, University of Alabama Press: Tuscaloosa.

Staeck, Klaus 1984, Staecks Umwelt. Texte und politische Plakate, Göttingen: Steidl.

Van den Heuvel, Maartje and Metz, Tracy 2008 (eds.), Nature as Artifice. New Dutch Landscape in Photography and Video Art, Rotterdam: NAI.

Werkstatt für Photographie 1980 (eds.), Michael Schmidt und seine Schüler, Berlin: Werkstatt für Photographie.