The Rise of Dutch Landscape Photography. How a Vision of Painting entered Photography

Abstract

In the discourse on the way in which visual art reflects and shapes our image of landscape – popular in the area where cultural geography and art history overlap – this article addresses the emergence of Dutch landscape photography. It spans a period beginning with stereoscopic photography of the 1850s to the pictorialist photography that was still being produced in the Netherlands during the 1930s. Attention is especially paid to the influence of an archetypical image of the Netherlands that was profiled in the second half of the nineteenth century by the painters of the so-called Hague School, such as Willem Roelofs, Jozef Israëls, Anton Mauve and Jan Hendrik Weissenbruch. In their paintings, Holland was a watery polder land with windmills and cows, inhabited by humble peasants and fishermen. It has been pointed out that, around 1900, this painterly image of the Hague School migrated from painting into artistic and touristic photography. The first to seek a painterly vision of Dutch landscape in the style of the Hague School with their cameras were photographers from abroad, including James Craig Annan, Alfred Stieglitz and Heinrich Kühn. Hereafter, Dutch photographers such as Adriaan Boer, Berend Zweers and Henri Berssenbrugge followed.

Article

From the 1980s on, art history and geography have developed a common interest in the way visual art shapes our mental image and understanding of landscape. In geography, Denis Cosgrove and Stephen Daniels – particularly in their book The Iconography of Landscape of 1988 – have emphasized the importance of visual art in landscape representation and geographical imagination.[1] In art history, W.J.T. Mitchell has done important work in researching landscape pictures as cultural expressions that represent spaces in ways that we want these spaces to be understood culturally. In Landscape and Power from 1994, he even suggests that the word landscape be interpreted as a verb, i.e. ‘to landscape’, in order to further clarify this mechanism.[2] In the field of photography, Liz Wells has discussed landscape pictures as critical practices that render meaning to environments that were photographed. Important are her recent book Land Matters from 2011, as well as the exhibition Sense of Place. European Landscape Photography, which she curated at the Bozar Museum in Brussels in 2012.[3]

Following these approaches, ‘landscape photography’ in this article is to be understood as photography that shapes our meaning of the land at which the camera is aimed. As Wells has pointed out, ‘landscape photography’ refers to the photography of nature and rural areas in the land. This originally pastoral connotation of ‘landscape’ becomes clear from the fact that other types of land are being referred to with specific indicators like ‘cityscape’, ‘seascape’, ‘industrial landscape’, etc.[4] In this case, landscape photography is being considered as an artistic genre, as an equivalent of the landscape genre in painting. In contrast to the depiction of landscapes in engineering, topographic, and nature photography, artistic landscape photography is a critical type of photography, which is not trying merely try to inform, but which also wants to contemplate our mental images of landscapes. Although it also deals with mental images of landscapes (‘dreams’, as described by John Taylor in Dreams of England from 1994), touristic photography is a less critical genre of photography.[5] Touristic photography is thought to confirm and repeat landscape images, thus turning them into stereotypes. Let us now examine how landscapes were photographed in the Netherlands during the nineteenth and early twentieth century, within the context of these various photographic directions.[6]

Early touristic photography

During the second half of the nineteenth century, in the era before the intensive distribution and consumption of the illustrated press, photographic prints, both individually and in series, began to respond increasingly to people’s growing mobility and the rise of tourism.[7] From about 1850 on, stereo photography (the nineteenth-century precursor of ‘3D photography’) was a very popular medium by which images of countries and peoples reached the public. Later, photographs in carte-de-visite, picture postcard, or even larger formats were produced, distributed and collected separately in series via cassettes or albums.[8] By the mid-nineteenth century, the Netherlands was connected to the European railway network, and from the 1870s onward, to the lines of steamships traveling to the United Kingdom and the United States. When in 1858 the French publisher Alexis Gaudin et Frères made an early series featuring 71 vues stéréoscopiques of the Netherlands, these images showed Dordrecht, Rotterdam, The Hague, Amsterdam and Haarlem: precisely those cities that could be reached by train.[9]

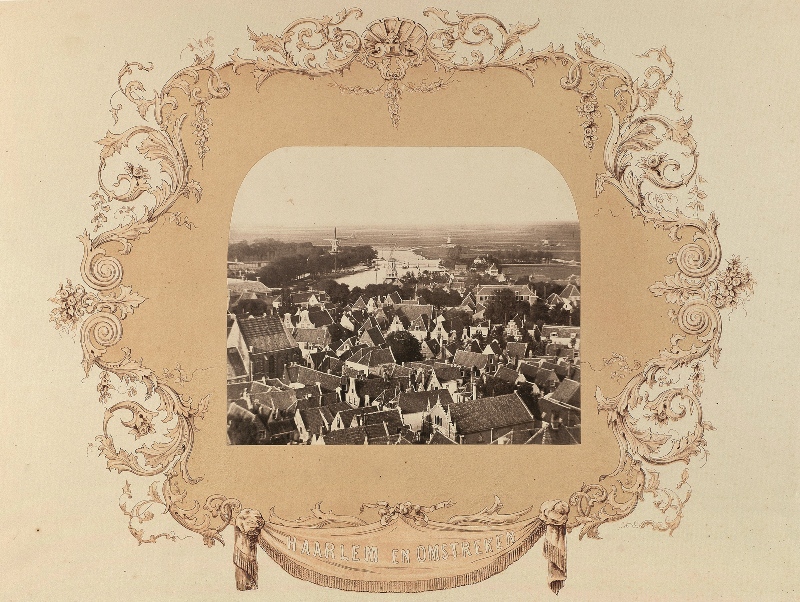

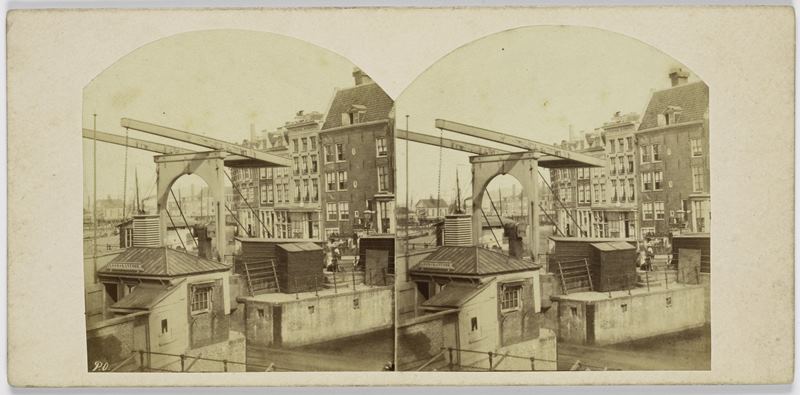

Rather than an unruly depiction of reality, touristic photography imagined a ‘dream’ of a destination.[10] The dream associated with this touristic journey to or across the Netherlands was that of the Golden Age.[11] When considering Gaudin et Frères’ aforementioned series, the Stereoscopische Gezichten in Nederland (1858), the Vues de Hollande (1859) by Pieter Oosterhuis, as well as the stereoscopic photographs of Netherlands that were distributed by the French publisher Braun et Cie starting in 1864, all clearly demonstrate that this quintessential dream of the Netherlands was chiefly to be found in the country’s cities. [ill. 1] It was a notion with a prehistory of its own: one already existing in the genres of topographic painting and drawing.

|

[ill.1] Pieter Oosterhuis and Andries Jager, View of herring packing department, Amsterdam, 1859, stereoscopic photograph, Rijksmuseum, inv. no. RP-F-F11651 |

In the last decade of the nineteenth century, the awareness grew that photography of the rural Netherlands as well carried potential for tourism. Carl Wilhelm Bauer, who Rijkswaterstaat (which is part of the Dutch Ministry for Infrastructure and the Environment) also commissioned to do engineering photography, revealed the scenic beauty of the Dutch province of Zeeland in photographs of dunes and country estates that he had taken starting in the 1870s. In 1892, Bauer became a board member of Zeeland’s first Tourist Information Office VVV (an abbreviation for the Dutch ‘Vereeniging voor Vreemdelingen Verkeer’).[12]Ons eigen land (Our Own Country) was the first book on the beauty of the Netherlands in which photography was given the most prominent role.[13] One of the book’s two authors, G.A. Pos, was the second chairman of the Dutch Touring Club ANWB. Pos’ co-author, G.L. Hasseleij Kirchner, was one of the first cyclists to take photographs while touring the country from 1889 onward.[14]

Engineering and topographic photography

Although the rise of touristic photography was related to the building of the railroads, with many a tourist traveling to the Netherlands by train, these modern innovations introduced to the landscape were in themselves by no means a subject for the tourist gaze. Instead, they belonged to the domain of engineering photography.[15] [ill. 2] Photographers like Johann Georg Hameter and Pieter Oosterhuis photographed the modernization of the Dutch landscape and the great infrastructural projects commissioned by the Royal Institute of Engineers (or KIVI, the abbreviation of the Dutch ‘Koninklijke Instituut Van Ingenieurs’), Rijkswaterstaat, and the National Railways among others. These images, however, were never part of any collective notion regarding the image of ‘the typical Dutch landscape’. They were found only in the publications and archives of those institutions that commissioned these products, or in the luxurious cassettes and albums that were distributed as public relation gifts.[16]

|

[ill.2] J.G. Hameter, Iron dry dock, after 1883, carbon print, 27,5 x 47,0 cm, Leiden University Library, inv. no. PK-F-54.46. |

Oosterhuis in particular, whose stereoscopic series of Dutch cities are cited above, attained a high level of quality in engineering photography.[17] Although educated as a painter, Oosterhuis incorporated virtually no aspects of pictorialism in his photography, nor did he have any contact with the painters of the Hague School. For him, the countryside was most interesting when robust architecture could also be seen, e.g. a bridge or sluice, or some other engineering-related activity. His clear images possess a great sharpness in detail. Oosterhuis chose to include both the urban and modern elements in the landscape, and by choosing his camera’s point of view intelligently, his photographs acquired strong geometrical compositions and a striking perspectival depth. This makes Oosterhuis a precursor of the twentieth century movement in New Photography and allows us to refer to his work as ‘pre-modernist’.

Pioneers of Dutch landscape photography: Munnich & Ermerins and Tinne

The first pioneers of Dutch landscape photography were amateurs who took up the camera as a leisure activity. Photography in the nineteenth century was a labour-intensive, expensive and technical novelty, which, besides time and money, also required knowledge of or at least a feeling for physics and chemistry.[18] Examples of high quality landscape photography from France had reached the Netherlands by the mid-nineteenth century. Landscape photographs by Éduard Baldus, Bisson Frères, and Louis Alphonse de Brébisson, as well as sea views by Gustave Le Gray, were all part of the Exhibition of Photography and Heliography in 1855, 1858 and 1860 in the artists’ society ‘Arti et Amicitiae’ in Amsterdam.[19] In the decades that followed, when the painters of the Hague School were working in the Dutch landscape, these powerful foreign landscape photographs had virtually no following in the Netherlands.

An interesting exception is the remarkable photographers’ duo. Johannes Munnich, a mathematician and physicist, and Robbert Ermerins, a jurist, who took the most convincing early landscape photographs of the Netherlands.[20] Although starting out as amateur photographers, the two men ran the professional ‘Photographic Establishment Munnich & Ermerins’ in Haarlem, to the west of Amsterdam, for a brief period, from October 1860 to December 1861.[21] In 1858, they climbed the tower of the St. Bavo Church – the town’s main church – and photographed the landscape of Haarlem and its surroundings in different directions. [ill. 3] The duo are certain to have been aware of just how artistically charged the landscape of Haarlem was. Going back to the seventeenth century, when Haarlem was an important center for landscape painters like Jacob van Ruisdael, ‘views of Haarlem’ have always been popular in Dutch art history.

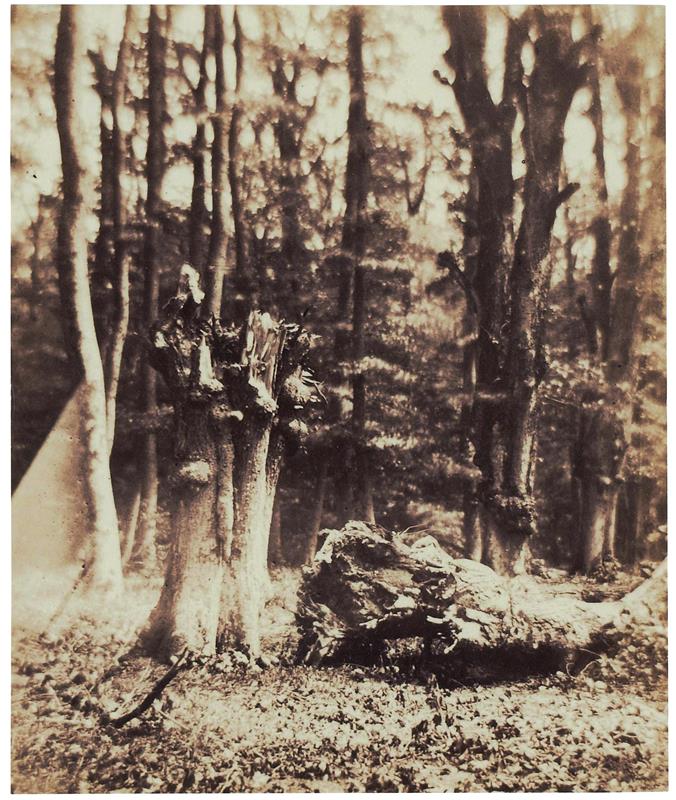

On 30 May 1860, Munnich photographed trees in Haarlem that had fallen over during a storm the day before. [ill. 4] Not only was the photographer struck by the ‘journalistic’ value of this event, but he seems also to have been struck by the vanitas character of the fallen tree – an image known from art history. In order to find the right composition and the play of forms, he experimented with photographs in landscape and portrait format. Another picture, also from 1860, shows a birch-lined road. The lack of documentary or topographic content, together with the prehistory of the motif of the tree-lined road, places this picture in the landscape tradition of painting. [ill. 5] The artistic ambitions of Munnich and Ermerins are evident in the fact that they managed to get three photographs exhibited in the fourth exhibition of the Société française de photographie in 1861 in Paris.[22] One of their photographs bore the title Vue prise dans les dunes près de Harlem, a phrase very similar to the names often bestowed landscape paintings. With the geographical addition of ‘près de Harlem’ – where the great painters had also been working – they probably wished to stress the association with the painterly tradition to an even greater degree.

|

[ill.5] Johannes Munnich and Robbert Ermerins, Bloemendaalsche Bosch (‘Woods of Bloemendaal’), 1860, gelatin silver print , 15 x 10 cm, Noord-Hollands Archives, inv. no. 54-006984. |

Another dedicated amateur photographer was Alexandrine Tinne.[23] This noblewoman of standing from The Hague worked with large-format negatives and cameras, and used the wet collodion process. The photographer had to apply light-sensitive emulsion to the glass plate, expose the plate in the camera to light while the emulsion was still wet, and develop and fix the negative image immediately on the spot.[24] In these days, many photographers carried a portable tent with them in those days to function as a mobile darkroom. Tinne, who was most stylish, employed a coach for this purpose. From the window of her house on the Lange Voorhout in The Hague, Tinne photographed a triptych of treetops that was most peculiar for those days. [ill. 6a, b, c]. Rather than a landscape, this image may be considered an exercise with the camera, or even a figure study.

One day in 1861, Alexine – as she wished to be called – had her coach driven to the dunes nearby The Hague. There she made an image that, together with those by Munnich and Ermerins, belongs to the earliest landscape photographs of the Netherlands. [ill. 7] The key element of this picture is an ash tree that was planted by King William II. Tinne chose not to place her camera more towards the front – something, that would have made the tree fill the entire image and consequently turned it into the main subject. Instead, she placed it left of the path, in the vegetation of the dunes. That Tinne was sensitive is special compositions is known from her other pictures, in which she created balanced geometrical forms. With this viewpoint, Tinne chose for a wide view of the dunes, while the horizon, the line of the vegetation in the front, the tree and the bushes form a consciously chosen composition. As a result, this image can certainly be called a landscape photograph. Neither Alexandrine Tinne, nor Munnich & Ermerins brought about Dutch landscape painting: they were only pioneering soloists.

The Hague School of painting

In the second half of the nineteenth century, it was the painters of the so-called ‘Hague School’ who strongly profiled an image of the Dutch landscape. In actuality, they were breathing new life into an old tradition of Dutch landscape painting that had its origins in the seventeenth century. Ernst Gombrich, and later Ann Jensen Adams and Simon Schama, clearly demonstrated how it was a Dutch need for a bourgeois identity based on the young seventeenth-century republic that lay at the very heart of the genre of landscape painting as it came into being.[25] The image of the Netherlands created by the Hague School was closely connected to the winning of land by ‘reclaiming’ it from the sea, rivers and marshes, but also to the culture of austerity in the lives of farmers and fishermen that was inspired by Protestantism.[26] The waterscapes with polders, cows, and windmills painted by Willem Roelofs, Paul Gabriël and Jan-Hendrik Weissenbruch amongst others, as well as the scenes of fishermen’s life by painters such as Jozef Israëls and peasants’ life e.g. Anton Mauve’s shepherds are iconic. [ill. 8]

|

[ill.8] Jan Hendrik Weissenbruch, Track boat canal, 1870, oil on canvas, 65 x 100 cm, Gemeentemuseum Den Haag |

Although photography soon reached the Netherlands after its invention in 1839, few of the Hague School artists took up the camera to study and depict the landscape. This is all the more remarkable when considering that, earlier in the nineteenth century, the French painters of the Barbizon School, who were an important inspiration for the Hague School, had done this very thing. Among artists of the Barbizon School, a vivid dialogue emerged between photography and painting. In the woods of Fontainebleau in France, both painters and artists were working with cameras.[27] Their painting and photography express a similar fascination for the beauty, atmosphere and grandeur of nature and the simplicity of farmers and herders who live in harmony with it. Eugène Cuvelier, an important photographer who was trained as a painter and lived in Fontainebleau, produced a large oeuvre of landscape photographs that were famous, much admired and frequently discussed by the Barbizon painters.[28] Some of the photographers were trained as painters: they often practiced painting and photography simultaneously. The painters Millet, Jean-Baptiste Camille Corot and Gustave Courbet collected photography. Photographic studies of nature and landscapes were amply available, for example through the Études Photographiques and Études et paysages albums by the Parisian publisher Blanquart-Évrard.

Among the painters of the Hague School, little is known about such photographic activity.[29] Matthijs Maris was interested in the photographic experiments of the painter Lawrence Alma-Tadema, had built a camera obscura, and was very pleased with a stereoscopic camera that he had received as a gift.[30] In 1871, he painted his Souvenir d’Amsterdam after a stereoscopic photograph by Pieter Oosterhuis.[31] Later, however, Maris spoke somewhat condescendingly of this matter. In 1905, he professed an ideal that was more in line with the artistic environment of his day: he wanted ‘to invent [his] models and landscapes. They do not exist in nature’.[32] Moreover, two years later he wrote, ‘My pictures are inside me’.[33] If in the nineteenth century Dutch painters used photography as study material to any extent, they did so covertly in order to avoid being viewed as incompetent.[34]

Dutch landscape in foreign pictorialist photography

In the nineteenth century, it was foreign pictorialist photographers who took artistic photographs of the Dutch landscape that were inspired by the Hague School.[35] Pictorialists were photographers who, from the late nineteenth to the early twentieth century, gave photography a strong impulse as a fine art medium by remediating ideas, subjects and compositions derived from painting into photography.[36] By introducing labour-intensive printing techniques, which required a substantial amount of handiwork, they increased the exclusivity and expressive power of their photos.[37] ‘Softness’ (achieved primarily through blur) and the chiaroscuro (the use of light-dark contrasts) were important for pictorialists. Especially with respect to the use of chiaroscuro, Dutch painting was recommended on more than one occasion and cited in influential literary sources as example for photographers.[38]

The Scottish pictorialist James Craig Annan visited the Netherlands in 1892, taking hundreds of photographs. During Annan’s previous visit to the Netherlands, he had been moved by the flat and marshy character of the grey land.[39] It was seeing the International Exhibition in Glasgow in 1888, where paintings of the Hague School were on display, that had inspired him to produce photographs.[40] Besides the cities of Amsterdam and Utrecht, he also visited smaller towns, such as Alkmaar and Haarlem. There he photographed farmers and fishermen in the vicinity of Zaandam and Zandvoort, among other locations. His photograph of a shepherd with his flock near Utrecht – a motif that was also popular among the painters of the Hague School – was praised by British critics.[41]

Through the international ‘traffic’ of pictorialism, Annan’s photographs of the Netherlands where shown not only in Glasgow, but also in London, New York and Hamburg, where he would also sell photographic prints as fine art.[42] It is not difficult to imagine to what degree the international public must have appreciated these photographs, given the fame of historic Dutch landscape painting. From the European tour of the famous American pictorialist Alfred Stieglitz, twenty ‘Dutch subjects’ have been passed down to us, e.g. Scurrying Home, a scene of two fisherwomen walking towards a distant church – an image that can easily be classified with the Hague School’s fishermen motif.[43] [ill. 9] Annan himself expresses his inspiration for making his photographs inspired by the Hague School. He states that it was in the Netherlands that he found ‘the green fields, romantic windmills, and shepherds with their flocks, which serve as inspiration for the grand pastoral pictures of Israëls and his followers’.[44] The Austrian photographer Heinrich Kühn, as well a key figure in international pictorialism, paid visits to the Netherlands in 1897, 1901 and 1904, during which he made photographs in the traditional seaside villages of Katwijk and Noordwijk. After 1900, even more foreign pictorialists would come to the Netherlands to take photographs. By this time, however, pictorialism also had emerged among Dutch photographers, who themselves turned their cameras in the direction of the Dutch landscape.[45]

Dutch landscape in foreign touristic photography

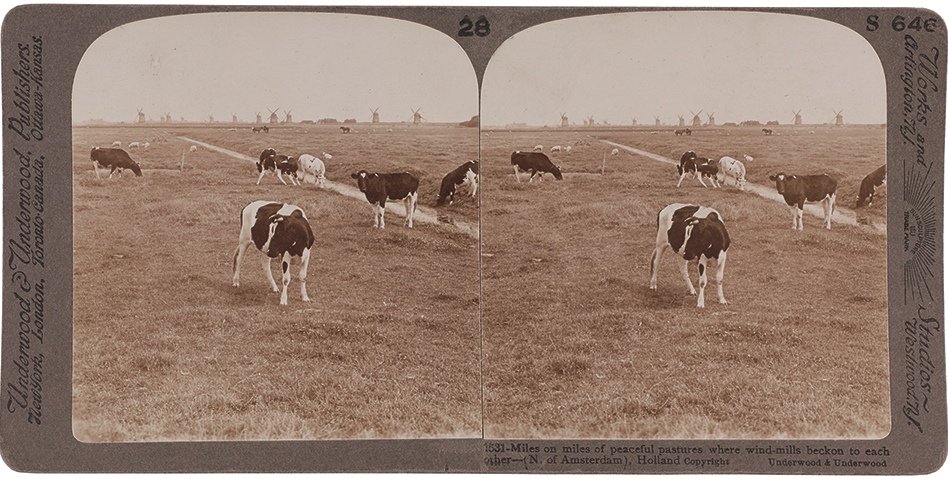

A series of stereoscopic photographs about Holland from 1905 by the Canadian/American firm Underwood & Underwood shows that, shortly after the turn of the century, meadows, cows, farmers, the fisherman’s life, and genre pictures depicting daily life in the country had also become part of the touristic image of the Netherlands [ill. 10] The influence of painting of the Hague School can likewise be demonstrated here. Some of the verso sides of these stereo photographs mention the book Dutch Life in Town and Country by P.M. Hough, which appeared just a few years before in 1901. It seems as if the photographer who visited the Netherlands in 1905 might have carried it in his hand luggage.[46] Hough wrote about the painters of the Hague School, but only after having mentioned that ‘the art of a country is ever in unity with the character of the people’. He also added: ‘If this is true of all countries, it is nowhere so visibly true as in Holland.’[47] Hough describes the beach views by Jacob Maris, the cow-filled meadows by Willem Maris, the grey, misty landscapes by Matthijs Maris, sea views by Hendrik Willem Mesdag, and the life of fishermen and women by Jozef Israëls.[48] He praises the painting of that day by writing that ‘Dutch art was never more virile, more original, more self-conscious than today, when it is represented by a band of men whose genius and enthusiasm recall the great names of the past’.[49] The references to Hough’s book found on the stereoscopic cards verify that this was the inspiration that directed the photographer’s choices with regards to subject matter and composition. They also make it clear to the person viewing these stereoscopic cards that painters of the Hague School had depicted the Netherlands – and what Hough had interpreted as being ‘typically Dutch’ – was what defined the manner in which the images were to be interpreted and understood.

Landscape in Dutch pictorialism

Particularly after 1900, Dutch pictorialists also adopted the artistic approach to the Dutch landscape in photography. In terms of content and style, the painting of the Hague School was their most important source of inspiration.[50] Photographic reproductions of paintings were readily available, for example, through their distribution by the company Goupil & Cie.[51] The Haarlem-based photographer Adriaan Boer made his living primarily from portrait photography. In his spare time, however, he also made genre-like paintings: Boer’s heath landscape with a flock of sheep is highly reminiscent of the Hague School. [ill. 11] Henri Berssenbrugge, who as well made his living chiefly from commissions for portraiture, photographed farmers’ life in the southern province of North Brabant, where he lived from 1901 to 1906.[52] These photographs not only provided an elaborate documentation of rural life, but they were also related to the image of the Dutch countryside as portrayed by the Hague School.[53] [ill. 12] That Berssenbrugge’s rural landscapes also fit the tourists’ image of the Netherlands, is illustrated by the fact that several of his images also appeared in the form of picture postcards. [ill. 13] Berend Zweers – as well mainly a portrait photographer – is known to have photographed the dunes near Haarlem in his spare time. [ill. 14] The Amsterdam=based Bernard Eilers – who earned his income from portrait photography, but also from making art reproductions, including paintings in the Rijksmuseum – photographed picturesque polder landscapes that featured dramatic cloud-filled skies in the vicinity of Amsterdam.[54] [ill. 15]

|

[ill.11] Adriaan Boer, Towards the fold, 1905, photogravure, 15,5 x 22 cm, Nationaal Archives (Spaarnestad Collection), The Hague, inv. no. SFA003010582. |

|

[ill.12] Henri Berssenbrugge, Field Labour, 1902, direct carbon print, 16,3 x 11,0 cm, Leiden University Library, inv. no. PK-F-53.306. |

|

[ill.13] Henri Berssenbrugge, Untitled [landscape with mills], s.a. [1930’s], postcard with gelatin silver print, Leiden University Library, inv. no. PK-F-B.2676 |

|

[ill.14] Berend Zweers, Untitled [dunes near Haarlem], 1905-1910, carbon print, 19,5 x 29,9 cm, Leiden University Library, inv. no. PK-F-G.502. |

|

[ill.15] Bernard Eilers, Towpath near the Schinkel, Amsterdam, 1907, bromoil print, 27,8 x 39,4 cm, Leiden University Library, inv. no. PK-F-06.047 |

Remarkably, the Dutch pictorialists created an image of the Netherlands that was barely modern and almost nostalgic. Man’s intervention in the landscape was depicted by Underwood & Underwood, while trains were included in the painter Paul Gabriël’s painting Il vient de loin (ca. 1887) as well as Alfred Stieglitz’s famous photograph The Hand of Man (1902). The new harbour works at Enkhuizen on the IJsselmeer were painted by Mesdag between 1885 and 1886. The Dutch pictorialists, by contrast, stayed far away from these kinds of modern elements in the Dutch landscape in the years after 1900.[55] Perhaps it was precisely this nostalgia that motivated the modernist New Photography movement’s resolute rejection of the pictorialists’ motif of the rural landscape during the Interbellum. Well into the twentieth century – even as late as the 1990s – the landscape would remain an unpopular subject in Dutch photography.[56]

Nature photography

In addition to the topographic, engineering and pictorialist photographers, after 1900 there also emerged the new ‘nature photographers’, who began to explore the Dutch landscape with their cameras. Among them, Richard Tepe was a remarkable figure, who specialized in photographing the flora and fauna of the Netherlands. [ill. 16] From an art historical point of view, Tepe was a solitary individual who maintained a substantial distance between himself and the Dutch art scene. From the perspective of photographic history, however, Tepe is significant because he wrote about the skills and techniques required for nature photography. One such example is his booklet De jacht met de camera (‘The Hunt with the Camera’) from 1909. Tepe’s writings would later become highly popular among a broad audience of amateur photographers.[57] The importance of Tepe’s photography lies in the fact that it provided the Dutch nature movement, as well as the work of its most outspoken spokesman, Jac. P. Thijsse, with a visual material. In other words, Tepe gave the nature movement a ‘face’: his vast oeuvre visualized the consciousness of the importance of nature and nature conservation in the Dutch landscape.[58] In some of Tepe’s photographs, the influence of the Hague School’s representation of the Dutch landscape is to be observed: there where man’s presence and scenes of rural life are depicted. In such cases, Tepe’s images of the humble Dutchman, who lives in harmony with nature, resemble paintings from the Hague School.

Amateur photography

With the arrival of portable box cameras and industrial photographic papers at the end of the nineteenth century, photography became both less labour-intensive and less costly. As a result, it came within the reach of a broader public. The new phenomenon of the ‘snapshot’ became a means to document experiences in one’s own environment, especially during peak moments in life and leisure. Nineteenth-century amateur photography, as passed down to us via family archives and photo albums, reflects the trips and holidays of ordinary people in the Dutch countryside. They quite frequently resemble an image that relates to the landscapes of the Hague School. People recreate in the same dunes that Mesdag once painted. Snapshots taken on the beach show well how the beach tourism of those days – with bare skin hidden away from view by an abundance of clothing, protective deck chairs and concealed bathing carriages – intermingled with the fishing boats. They also reflect the fishing activity of the day, which the Hague School had previously established as a visual theme. Children playing – wearing children’s fashion that was typical of the times – seem as if they had stepped right out of a painting by Jozef Israëls. [ill. 17] In amateur photography, one observes a charm of the Dutch landscape similar to that which was elevated into art by the Hague School. Moreover, it becomes evident that, via nachleben, these artworks had found their way into popular photography, e.g. touristic photography, essentially becoming part of the collective visual memory.

The Hague School, photography and the contemporary landscape

Recently, a photography commission granted by a coalition of Dutch nature organizations, which included Natuurmonumenten and Vogelbescherming (national associations for nature and bird conservation), also made use of the Hague School’s portrayal of the Dutch landscape.. In the highly malleable and manipulable Dutch landscape, discussions are always about how the land can be shaped and re-designed further. In the midst of climate change and rising seawater levels, nature organizations are pleading for solutions that are more nature-friendl, as opposed to robust, rock-solid alternatives, such as the building of large-scale water works and monumental seawalls. In centuries past, the latter approaches were most favoured, Today, however, they prove to have significant negative ecological effects on the environment. Photographer Loek van Vliet was commissioned to photograph four landscapes re-shaped by natural means in such a manner that the similarities with historical landscape painting becomes more evident. Visitors as well as inhabitants recognize these as landscapes that are more typically Dutch. They therefore appreciate them and ‘connect’ with them more readily. The raising up of a part of the south-western Dutch coast by damming up sand now protects this region from the destructive power of the rising sea level. As a result, however, this measure also provides an area full of nourishment for migratory birds. Van Vliet photographed this area following the example of the painting Beach with Shellfish Gatherers (1891) by Jan Hendrik Weissenbruch. [figs. 18, 19] As such, the painting of the Hague School – as re-interpreted by photography – today provides nature organizations with a visual, art historical argument in discussions concerning the redesigning of the Dutch landscape.[59] Such events clearly illustrate just how powerful and persistent the Hague School’s image of the Netherlands remains to this day.

CV

Maartje van den Heuvel is an art historian and curator of photography at the Special Collections of Leiden University Library. She is currently working on her PhD in art history at Leiden University.↑

Notes

1. Cosgrove and Daniels 1988.↑

2. Mitchell 1994, p. 1 ↑

3. Wells 2011 and 2012.↑

4. Wells 2011, p. 22-23.↑

5. Taylor 1994.↑

6. See also Frits Gierstberg, ‘Photography and Landscape in the Netherlands of the Nineteenth Century’, in: Bool 2007, pp. 192-198.↑

7. Goudbeek 2013, p. 11.↑

8. See the special issue on travel photography of Kunstschrift 2008.↑

9. Anneke van Veen makes this connection in Veen 2010, p. 37.↑

10. John Taylor made this comparison. ‘In its ideal form, touring is like dreaming’, he wrote in his book A Dream of England. Taylor 1994, p. 2.↑

11. Also Boom comes to this conclusion regarding touristic photography, in Boom 2012 under the heading ‘The Dutch Tradition’. See also Veen 2010, p. 35.↑

12. The photographs are part of the sub-collection of the Zeeland Association of Sciences in the Zeeland regional archive. See Goudbeek 2013, pp. 10-13.↑

13. This book appeared in 1908 as a commemorative book of the ANWB (see [note 25]), but contained photography that had been produced previously. Doornmalen 2013, p. 4.↑

14. Ibidem. ANWB is literally the abbreviation of ‘Algemene Nederlandse Wielrijdersbond’, meaning ‘General Dutch Cyclists’ Association’, but it became known for its research and service to all tourers, especially automobilists. ↑

15. Boom, Mattie, ‘Moderne Landschaft. Die Ingenieur-fotografie und das Bild der Niederlande’, in: Reynaerdts 2008, pp. 69-97.↑

16. Not until late in the twentieth century was engineering photography rediscovered and appreciated anew for its artistic and aesthetic qualities, which were in turn subsequently adopted by photographers and applied in general photography at this time. See Heuvel 2008. ↑

17. Bool/Veen, 1993.↑

18. Deserving special mention are a number of photographs by Eduard Asser from the 1850s, today preserved in the collection of the Rijksmuseum, such as inv. nos. RP-F-AB12280-J and RP-F-AB12279-Q. At first glance, these images remind us of the views of windmills by Jacob Maris or Paul Gabriël. However, these images may not be considered landscape photographs: the landscapes around the windmills play too marginal of a role, while Asser’s other photographs bear witness to a fascination primarily oriented towards country houses, castles and other buildings – not landscape. See Bool/Boom 1998, p. 10. ↑

19. For a discussion of these ‘Tentoonstellingen van Photographie en Heliographie’ and complete lists of exhibited works, see Boom 1997.↑

21. Ibidem, p. 1.↑

22. Ibidem, pp. 2-3, in the on-line article under the heading ‘Beschouwing’/’Discussion’.↑

23. Willink 2012. ↑

25. Gombrich 1966, p. ; Adams 1994, p. 35; Schama 1995, p. ↑

26. Adams 1994, pp. 38-39; Reynaerts 2008, pp. 55-57.↑

27. The information on photography and the Barbizon School is based on Sarah Kennel, ‘An Infinite Museum. Photography in the Forest of Fontainebleau’, in: Jones 2008, pp. 152-167 and illustrations on pp. 74-80 and 112-123.↑

28. The painter Théodore Rousseau, for example, described them elaborately in a letter to Jean-François Millet. Ibidem, p. 163.↑

29. See also Mattie Boom, ‘Moderne Landschaft. Die Ingenieur-fotografie und das Bild der Niederlande’, in: Reynaerdts 2008, p. 77.↑

30. Heijbroek 1975, p. 14.↑

31. Veen 1993, p. 29; Heijbroek 1975. ↑

32. ‘[Ik wil mijn] modellen en landschapjes uitvinden. Ze bestaan niet in de natuur’. Letter from Thijs Maris to A. Plasschaert, 15 May 1905, here quoted from Heijbroek 1975, p. 17.↑

33. Letter from Thijs Maris to W.J.G. van Meurs, 25 September 1907, here quoted from Heijbroek 1975, pp. 14-16, 29.↑

34. Well-known photographic archives of nineteenth-century Dutch painters are those of Willem Witsen and George H. Breitner. Witsen, in particular, portrayed people from his immediate surroundings via photographs, but he did not use his photographs as models for his paintings. Breitner, by contrast, did incorporate the artistic effects of photography in his portraits and Amsterdam street scenes. Neither of the two painters presented their photographs as final artistic results. ↑

36. See Daum 2006 [2005], in which Ingeborg Th. Leijerzapf writes about Pictorialism in the Netherlands; Ingeborg Th. Leijerzapf, ‘Moment, temperament and Atmosphere as Core Concepts, 1889-1925’ ,in: Bool 2007, pp. 103-145; Nordström 2008.↑

37. See Heuvel 2010, p. 14ff. For an explanation of the photographic techniques the pictorialists used, see ibidem pp. 151-152; Bool 2007, pp. 565-568; Dijk 2011. ↑

38. For example, by the important founder of Pictorialism, Henry Peach Robinson, in the key work The Pictorial Effect in Photography from 1868. Robinson about Rembrandt, see Robinson 1893 [1868], p. 109. The influential American magazine for artistic photography Camera Work discusses a portrait by Rembrandt in no. 3 of July 1903. See Heuvel 2010.↑

39. Boom 2012, under the heading ‘Pictorialism in photography’.↑

40. Leijerzapf in Bool 2007, p. 120.↑

41. Ibidem. ↑

42. Boom 2012, under the heading ‘Pictorialism in photography’.↑

43. Boom 2009, p. 91.↑

44. Boom 2012, under the heading ‘Pictorialism in photography’.↑

45. See Heuvel 2010 and Boom 2012 under the heading ‘Successors’.↑

46. Inhabitants of Zeeland, for example, are divided into the ‘dark’ and ‘light’ types, and the latter – with blond hair and blue eyes – is referred to with the description ‘of no particular beauty’. Hough 1901, chapter VIII ‘The Peasant at Home’, p. 77. ↑

47. Hough 1901, p. 165.↑

48. Ibidem, pp. 166-167.↑

49. With this, he refers to painters of the Golden Age, whom he briefly mentions in the passage before. Ibidem, chapter XV ‘Art and Letters’, especially pp. 165-166.↑

50. Although the art of the seventeenth century – ever so dominant and frequently cited in popular art – as well remained influential. See Heuvel 2010 for a more elaborate discussion of the nachleben of the nineteenth-century painting but also of the seventeenth-century painting in Dutch Pictorialism.↑

51. See remark by Boom in Boom 2012, note 13 of that article.↑

52. See Leijerzapf 2001 and Heuvel 2010, pp. 24-47. ↑

53. Nieuwenhuijzen 1976. Hundreds of glass negatives and prints of the North Brabant country life by Berssenbrugge are part of the North Brabant regional archives in Tilburg. ↑

54. Bool/Veen 2003, pp. 166-168.↑

55. One such exception was Bernard Eilers, who as an art photographer approached the Stedelijk Museum with ‘atmospheric’ photographs of building sites and activities in the Dutch capital. See a series of 1908 on a building site with pile drivers adjacent to the Amsterdam Central Station in the collection of the Amsterdam City Archives. Other pictorialists, like Berssenbrugge, will shift to more modern elements in the landscape. In their case, however, this coincides with a total transition to another, more modernist form of photography. ↑

56. The 1989 exhibition Hollandse taferelen/Dutch Scenes, with photography by Hans Aarsman, in the Amsterdam Stedelijk Museum marked a turn, after which the theme of landscape was again widely addressed. See Heuvel 2008.↑

57. Kuhlmann 2007, p. 20. ↑

58. He worked for popular publications concerning nature in the Netherlands, such as those of Natuurmonumenten. A photograph of a nest of spoonbills on the Naardermeer, comparable to the one shown here, was printed on the cover of the first issue of the Dutch nature magazine Buiten, 1(1907)1, p. 1. See Kuhlmann 2007.↑

59. Smallenburg 2014, pp. 10-11.↑

References

Adams, Ann Jensen, ‘Competing Communities in the “Great Bog of Europe”. Identity and Seventeenth-Century Dutch Landscape Painting’, in: Mitchell 1994, pp. 35-76

Amade, Pia and Ingeborg Leijerzapf, Willem Witsen, Geschiedenis van de Nederlandse fotografie, 5 (March 1988) 8, see also Depth of Field, http://journal.depthoffield.eu/vol05/nr08/f02nl/en (Accessed on 16 December 2014 ).

Berger, Wout, When I Open my Eyes, Salzburg (Fotohof) 2012.

Bool, Flip et. al. (ed.), text by Anneke van Veen, Pieter Oosterhuis [1816-1885], Amsterdam (Fragment) 1993.

Bool, Flip et. al. (ed.), text by Mattie Boom, Eduard Isaac Asser [1809-1894], Amsterdam (Focus) 1998.

Bool, Flip et. al. (ed.), text by Anneke van Veen, Bernard F. Eilers 1878-1951, Haarlem (Focus) 2003.

Bool, Flip et. al. (ed.), Nieuwe geschiedenis van de fotografie in Nederland: Dutch eyes, Zwolle (Waanders) 2007.

Boom, Mattie, ‘De Amsterdamse fotografietentoonstellingen van 1855, 1858 en 1860’, Geschiedenis van de Nederlandse fotografie, 14 (April 1997) 28, see also Depth of Field, http://journal.depthoffield.eu/vol14/nr28/f05nl/en (Accessed on 15 December 2014).

Boom, Mattie, ‘Moderne Landschaft. Die Ingenieursfotografie und das Bild der Niederlande’, in: Reynaerdts 2008, p. 69-97.

Boom, Mattie, ‘Heavy metal beats “greyer sky”. Interpretations of The Netherlands by foreign photographers 1890-1930’, Depth of Field, 3 (December 2012) 1, http://journal.depthoffield.eu/vol03/nr01/a03/en (Accessed on 15 December 2014).

Cosgrove, Denis and Stephen Daniels, The iconography of landscape: essays on the symbolic representation, design and use of past environments, Cambridge (Cambridge University Press) 1988.

Daum, Patrick et. al., Impressionist Camera: Pictorial Photography in Europe, London/New York (Merrell Publishers) 2006 [translation of La Photographie pictorialiste en Europe, 1888-1918, Rennes (Le Point du Jour/Musée des Beaux Arts) 2005].

Dijk, Jan van and Ingeborg Leijerzapf, Handboek herkennen fotografische en fotomechanische procedés: historische en moderne procedés en digitale afdruktechnieken, Leiden (Primavera) 2011.

Dijke, Frouke van et. al., Holland op z’n mooist. Op pad met de Haagse School, Zwolle/Dordrecht/Den Haag (WBooks/Dordrechts Museum/Gemeentemuseum Den Haag) 2015.

Doornmalen, Sil van, ‘Arcadisch Nederland. De jubileumuitgave Ons eigen land van de Algemene Nederlandse Wielrijders Bond in 1908′, Fotografisch geheugen (special about the landscape), 78 (Spring 2013), pp. 4-7.

Gombrich, Ernst, ‘The Renaissance Theory of Art and the Rise of Landscape’, in: Norm and Form, Studies in the Art of the Renaissance Landscape, London (Phaidon), 1966, pp. 107-121.

Goudbeek, Roosanne, ‘Bruggen en buitens. Verkenning van het Zeeuwse landschap door Carl Wilhelm Bauer’, Fotografisch geheugen (special about the landscape), 78 (Spring 2013), pp. 10-13.

Heijbroek, J.F., ‘Matthijs Maris en het “Souvenir d’Amsterdam”‘, Amstelodamum. Maandblad voor de kennis van Amsterdam, 62 (January/February 1975), pp. 14-18.

Heuvel, Maartje van den and Tracy Metz, Nature as Artifice. New Dutch Landscape in Photography and Video Art, Rotterdam (NAi Uitgevers) 2008.

Heuvel, Maartje van den et. al., In atmosferisch licht: picturalisme in de Nederlandse fotografie, 1890-1925 = In atmospheric light: pictorialism in Dutch photography, 1890-1925, Amsterdam (Rembrandthuis) 2010.

Hooghe, Alain d’, Rond het symbolisme. Fotografie en schilderkunst in de 19e eeuw, Antwerp/Brussels (Mercatorfonds/Paleis voor Schone Kunsten) 2004.

Hough, P.M., Dutch Life in Town and Country, London (George Newnes Ltd) 1901.

Jones, Kimberley (ed.), In the Forest of Fontainebleau. Painters and Photographers from Corot to Monet, exhibition catalogue Washington (National Gallery of Art), 2008.

Kuhlmann, Christiane, Richard Tepe: Photography of Nature in the Netherlands 1900-1940, Amsterdam (Rijksmuseum/Nieuw Amsterdam) 2007.

Kunstschrift (special about early travel photography), 52 (October/November 2008) 5.

Leijerzapf, Ingeborg Th. and Harm Botman, Henri Berssenbrugge passie – energie – fotografie, Zutphen (Walburg Pers) 2001.

Mitchell, W.J.T., ‘Introduction’ and ‘Imperial Landscape’, in: W.J.T. Mitchell (ed.), Landscape and Power, Chicago and London (The Chicago University Press) 1994, pp. 1-4, 5-34.

Nieuwenhuijzen, Kees, Henri Berssenbrugge. Straat- en landleven 1900-1930, Amsterdam (Van Gennep) 1976.

Nordström, Alison et. al., Truthbeauty. Pictorialism and the Photograph as Art, 1845-1945, Vancouver (Vancouver Art Gallery/Douglas & McIntryre), 2008.

Reynaerdts, Jenny and Joachim Kaak, Der weite Blick – Landschaften der Haager Schule aus dem Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam/Munich/Ostfildern (Rijksmuseum/Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen/Hatje Cantz) 2008.

Robinson, H.P., Pictorial Effect In Photography: Being Hints On Composition And Chiaroscuro For Photographers, London (Piper & Carter) 1893 [1869].

Shama, Simon, Landscape and Memory, London (Harper Collins Publishers), 1995.

Smallenburg, Sandra, ‘Schilderend met licht oude meesters achterna’, NRC Handelsblad, 20 August 2014, rubric ‘Het Grote Verhaal’, pp. 10-11.

Taylor, John, A dream of England. Landscape, photography and the tourist’s imagination, Manchester/New York (Manchester University Press) 1994.

Veen, Anneke van, ‘Munnich & Ermerins’, Geschiedenis van de Nederlandse fotografie, 15 (September 1998) 30, see also Depth of Field, http://journal.depthoffield.eu/vol15/nr30/f03nl/en (Accessed on 16 December 2014).

Veen, Anneke van, De eerste foto’s van Amsterdam 1845-1875, Amsterdam (Stadsarchief Amsterdam) 2010.

Wells, Liz, Land Matters. Landscape Photography, Culture and Identity, London/New York (I.B. Tauris) 2011.

Wells, Liz, Sense of Place. European Landscape Photography, Brussels/Veurne (Bozarbooks/Hannibal) 2012.

Willink, Joost, Reis naar het noodlot: het Afrikaanse avontuur van Alexine Tinne (1835-1869), Amsterdam (Amsterdam University Press) 2012.