Here Comes the Sun. Digital Springtime for a Collection in Hibernation

Abstract

The Belgian Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage (KIK-IRPA) is a scientific institute responsible for the documentation, study and conservation of cultural heritage. The backbone of its activities is partially defined by its historic photo collection, of which 4% had never been catalogued until recently. Officially non-existent, over time these photographs had become as ghosts in the collection. Facing a high degree of disassociation, a specific methodology in order to retrieve essential metadata (e.g. author, subject, etc.) was developed. Using traditional approaches such as comparative studies, looking at the photographic documents as primary material sources, and using new digital technologies and (internet) tools, it was possible to reinstate these images not only in the photo library of KIK-IRPA, but also as cultural heritage in the digital world and beyond. Following a hibernation of more than a half-century, a bright future now awaits these once forgotten photographs.

Article

Introduction

The Belgian Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage (KIK-IRPA) is a scientific institute responsible for the documentation, study and conservation of Belgian cultural heritage. The backbone of the institute’s activities is partially defined by its photo collection. A collection assessment of these photographs has revealed that approximately 4% have never been catalogued or identified. Officially non-existent, over time these supports had virtually become ghosts in the collection, about which little or nothing was known. What did these photographs depict? To whom did they belong? How did they end up in the collection storage area? Why were they never catalogued? But more importantly, how are to we answer these questions when a century has passed since these images were created? In other words, how do we transform our so-called ‘phantom’ photographs into images that are clearly visible in the digital realm?

The photo library of the Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage: ‘The nation’s visual memory’[1]

The creation of KIK-IRPA dates back to the 1930s at the Belgian Royal Art and History Museum (KMKG-MRAH), when Paul Coremans (1908-1965), a PhD professor in chemistry and an advocate of Belgian cultural heritage, was named head of the Service of Belgian Documentation and created the Physics and Chemistry Research Laboratory. It was not until 1957 that the institute, which became independent in 1948, received its current name.[2] One of its most important tools is a collection of more than 950,000 photographs. Over the years, this photographic library has gradually expanded in size and still continues to grow. One of the main sources of these photographs is closely linked to the context of the two world wars. KIK-IRPA was able to recover 10,000 photographs reflecting the cultural heritage of Belgium, which were originally commissioned by the German military command during the First World War and taken in the German-occupied territories. Coremans himself headed an emergency effort to inventory the nation’s heritage that was continued for the entire duration of the Second World War, resulting in the production of 160,000 photographs.[3] The collection has also grown through purchases or donations made by institutions and private photographers, photographic surveys conducted by Belgian museums, as well as a photographic inventory of works of art preserved in Belgian religious buildings that was initiated in 1968. At present, the photo library’s expansion is based primarily on photographs taken during restoration treatments conducted at KIK-IRPA, as well as frequent photographic inventories carried out within the context of art historical research. These photographic archives – with KIK-IRPA simultaneously preserving both the original capture medium and a printed version for consultation – serve as an irreplaceable visual inventory as well as an extraordinary tool in the study, promotion and protection of the nation’s heritage.[4]

Photography as a research tool

During the nineteenth century, influenced by scientific and technological innovations, there was a growing perceived need to document the world as objectively as possible.[5] The utopian idea of creating a ‘neutral’ image was met by the development of photography, which was seemingly able to simply register without adding any subjective interpretations.[6] One of the first initiatives to use photography for the documentation of heritage in a systematic manner dates back to 1845 at the Minutoli Institute of Liegnitz, only six years after the daguerreotype had been introduced to the world.[7] The best-known early example of photography as a tool in the study of heritage is perhaps the Mission Héliographique, commissioned by the French Commission des Monuments Historiques in 1851. By the mid-1850s, photography was an established instrument of knowledge transfer.[8] As a result, the medium fell victim to an imposed pictorial language, where systematic viewpoints (for example, a frontal view in combination with side views taken from imposed angles of 45°), a neutral illumination, and an extreme depth of field and sharpness were the rule.[9] Very soon, photography was being used in art historical research as a tool to create a visual thesaurus of monuments, artefacts and events. This concept has influenced our vision of art, history, and society ever since.[10]

A collection of ‘A’-nonymous photographs

Apart from images that serve primarily to document heritage in a strict sense, KIK-IRPA’s photo library also has many photographs that capture events and immortalize individuals. These are classified as ‘photo reports’.[11] This type of photography makes up the bulk of an unidentified collection of negatives that was recently rediscovered during a re-inventory of the photographic storage area. (Figs. 1 and 2) The collection, called ‘A’ for ‘anonymous’, attracted particular attention when an extensive digitization project was set up in 2013. At this time, this small collection of about 1600 estimated supports, consisting of camera originals – negatives on glass plates and nitrate films – and a few scrapbooks with a number of positive prints on paper, was thought to date back to the institute’s early beginnings. Moreover, the supports’ precarious state required immediate conservation and digitization in order to safeguard the images for the future. In addition, the relatively modest size of this collection, when compared to others, provided an opportunity to test our digitization methodology, such as the setting up of the equipment and the practical organization of the work between team members. It also involved an estimation of the time it would take to carry out the complete procedure, from the conditioning and repackaging of the historical supports to the entering of their descriptions into our database. Finally, the complete lack of context-related metadata concerning these photographs provided us with an exciting research challenge.

Towards a new future in the digital era

At the time the collection was first discovered, it was facing several risks: almost all of the supports were displaying one or more signs of decay, while the housing materials were found to be unsuitable for ensuring their long-term preservation. Most of the glass plates displayed a high degree of silver mirroring, as well as many forms of mechanical damage (scratches, encrusted dust, fingerprints, etc.) resulting from improper care in the past. The nitrate films demanded an immediate intervention, as the supports were already exhibiting signs of nitrate degradation, a highly destructive process. In addition to discoloration and extreme brittleness, most of these roll films were curled up completely.[12] Stabilizing the condition of the negatives was thus essential before digitization could take place.

The first step in the conservation process entailed cleaning. The glass plates were carefully removed from their old enclosures and submitted to a condition assessment, followed by an initial dry cleaning. Dust, residual mycelium and cardboard fragments from the boxes were then removed using a museum vacuum cleaner and soft Japanese brushes. Next, the glass surface of the plates was given a wet cleaning,[13] which allowed for the removal of mouldy stains, greasy fingerprints and other sticky substances. Finally, both the glass side and the emulsion layer – which could not be submitted to any wet treatment – were dry cleaned again. The nitrate films were only dry cleaned using a soft, anti-static, lint-free cloth to remove stains from the non-emulsion side of the negative.[14]

After cleaning, the supports were reconditioned in PAT-certified[15] paper enclosures. Fragile or cracked glass supports were inserted into four flap enclosures reinforced with museum cardboard. The nitrate films were housed in buffered paper sleeves. In cases of severe curling, they were rolled onto a paper cylinder with paper interleaves; this packaging was subsequently held in place using a neutral cotton string.[16] Once wrapped in their new enclosures, the negatives were assigned an official inventory number, at last acknowledging their existence within the institute’s collection.

To establish the technical standards, it was decided that digitization should be used to create so-called ‘preservation masters’,[17] i.e. digital copies of the originals,[18] whilst minimizing the risk of damage to the historic supports. As such, we opted to use a digital SLR to recapture the originals with the aid of a digital sensor, after which the image was post-processed using Adobe Lightroom and Photoshop. (Fig. 3) During these treatments, the negatives were converted into a positive image, the contrast restored, and the most obvious visual damages retouched. This allowed us to revalorize the images.[19]

A second digital youth for the collection’s ‘oldies’

Many photo libraries in research institutions have undergone significant changes in the management of their collections. In most cases, these photo collections were originally conceived as working tools, i.e. as visual research aides. As a result, during the course of the second half of the twentieth century, many of the historic supports in these collections were considered out-dated: black-and-white photographs were replaced by full colour versions, and by the beginning of the twenty-first century, most researchers preferred digital images.

If, by the 2000s, digitization made it possible for historically evolved image collections to be accessible online, today the very act of digitizing a photographic support opens up a whole new range of possibilities that greatly surpasses a mere glimpse of the image content.[20] Nowadays, the process is aimed at reproducing the historic support while at the same time respecting its material qualities, such as its mounting, the presence of annotations, etc. In most historical photo libraries, photographs were viewed as mere representations of the objects to be studied, with the latter forming the basis of the image’s description. Digitization allows us to identify and recreate several sub-collections that have been built up in the collection over the years and to research them as independent entities. This often provides us with a very different perspective of how these photographs were created in the first place as well as the context in which they originated.

Moreover, digitization allows the researcher to engage in a visual relationship with the photographs that is entirely new. High-resolution technologies make it possible to discover new details whilst zooming. Additionally, high quality digitization enables a view of the photograph in a new format, without being held back by the technical restrictions of enlargers, analogue printing media, etc. The digitization process can therefore mean a second life for historic collections, where supports once deemed old and no longer useful are bestowed a new functional significance.

Developing a method when looking for needles in a haystack

The biggest risk of loss – more so than the processes of degradation – was posed by disassociation. With nothing known about the photographs in this regard, the collection was essentially already lost. How could we recover what had once gone missing? Notwithstanding our conservation and digitization efforts, the first step in achieving their true restoration would entail the identification of these images’ content, the context in which they were created (author, date and place), as well as their provenance. In the case of a work of sculpture, its physical manifestation immediately establishes its existence. By contrast, an unidentified photograph – for which the material manifestation is viewed as inferior to the content[21] – is doomed for all eternity. In order to reinstate these historically significant supports as part of the collection, a proper description and identification of the image in BALaT, KIK-IRPA’s online database[22], was thus essential. In the current digital era, such metadata[23] are even essential to the very existence of a collection on the Internet. Without a basic description of the author or a keyword describing even a minimum of its content, a digitized image, no matter how beautifully composed, might just as well be dark data.

Archaeological excavations in the repository

A first strategy in recovering this information was to revert to the context of rediscovery. Here the collection was used as a material source in establishing the origin of an image. Looking at the material aspects of the photographs – e.g. their enclosures, as well as ancillary discoveries such as paper scribbles and annotations – information concerning the context of their making as well as the content could be retrieved.

The glass supports of the collection could be identified as gelatin dry glass plates: the negatives had a grey or black image colour and an evenly applied emulsion on a smooth, thin support. Their even sizes indicated that they were machine-made. This process was first described by Richard Leach Maddox (1816-1902) in 1871.[24] Introduced on the European commercial market in 1879 by Wratten & Wainwright in London, this element allowed us to date the collection between the 1880s and ca. 1925, the period in which these supports were produced.[25] Another kind of support was recognized as 4.5×6 cm, 6×6 cm and 9×12 cm nitrate cellulose roll films, a type of film that was produced from 1889 and commercialized by Kodak.

The fact that the supports were also preserved in the original enclosures of the glass plates allowed us to determine various data concerning the context of their creation. Each packaging states the production place and manufacturer of the negatives. For example, the 9×12 cm plates were almost entirely produced by the companies Antoine Lumière & ses fils (1892-1911) and Dr. Carl Schleussner in Frankfurt am Main (1860-1962). Other identified manufacturers are E. Graffe & J. Jougla, located in Perreux (1882-1911) and the company Joh. Sachs & Co, Aelteste Trocken-Platten-Fabrik in Berlin (established in 1883).[26] The 13×18 cm plates were produced by the company Nys & Cie from Courtrai, active between 1882 and 1910.[27] The name and place of the shop in Brussels where the photographer purchased his supplies could also be traced.[28] On several of the boxes, paper advertisements for the two last universal expositions[29] had been glued. Furthermore, written additions such as dates and place names, provided a first step in determining the date and the subject of the plates.[30] Some of the negatives were separated from each other by paper scraps, such as train timetables, letters and handwritten sheets. Particularly this last element provided a significant amount of information regarding the subjects of the images.[31] The elements described above provided us with an initial terminus post quem in establishing the date when the collection originated: the end of the nineteenth/beginning of the twentieth century.

Context provides meaning!

Based on the information derived from using the supports as a primary source, it was possible to re-establish the larger context in which the photographs were created. Several comparisons could be made with contemporary photographers and the collection could be positioned within the bigger historical picture (of photography). A comparison of the annotations on the boxes – citing places and specific events – with other sources also provided a definitive identification of the image content.

Although many locations in Belgium could easily be traced, such as views of Antwerp and Brussels, the identification of smaller cities and villages seemed infeasible at first. The most important material sources found within the context of the collection were ten brown-paper notebooks containing several positive prints that partially matched with the negatives. Some of the captions mentioned the exact date and place (for example, 15 juin 1902 Ferme de Stockel), making it also possible to identify pictures taken from a different vantage point (for instance E048920[32]).[33]

Looking at the collection as a whole, instead of image by image, allowed us to link several photographs, thus causing a chain reaction in their identification. For example, the photographer made several series during walkabouts and excursions. In one specific series, the first picture could be located near the Palace of Justice in Brussels. (Fig. 4) A number of the photographs show the city of Halle appearing in the background (E048179 shows the church of Saint Martin). Reconstructing this excursion, it became possible to locate and identify images along the Brussels-Charleroi Canal (E048176, E048180) that might otherwise have essentially been viewed as banal.

Comparing past and present

A similar comparative approach using the image content as a terminus post and ante quem enabled the identification and dating of the photographs. For instance, the clothing fashion observed in (group) portraits, as well as the location of specific buildings, works of art and monuments, made it possible to further specify the period identified. One example is a photograph showing the Sablon Church in Brussels in the background that was taken before the neo-gothic changes to the southern transept portal were introduced – a transformation that took place in 1908.[34] (Fig. 5) Furthermore, the west portal of the Augustine convent church is still visible on several photographs of the city centre. (Fig. 6) This building was situated on the Place De Brouckère until 1893, after which the church was demolished and the facade transported and reused in the building of the Saint Trinity Church in Ixelles (Brussels).[35]

|

Fig. 5. Emile-Henri t’Serstevens, The Church of Notre-Dame du Sablon in Brussels, 1890-1908. Glass plate, 9×12 cm. Brussels: Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage. © KIK-IRPA, Brussels, E048346. |

Visual comparisons with historic and contemporary sources are perhaps the most efficient method in describing and identifying the image content. Since the beginning of the twentieth century, postcards were printed for tourism.[36] Many of them have been digitized during the past years and are now accessible online.[37] Two photographs show a villa that remained unidentified until the same building appeared on a postcard: the Villa Genicot in Auderghem. (Fig. 7) (E048463) This building was named after its owner, mayor Jules Genicot (1852-1929), a figure who also seems to appear on a photo taken during a procession on the Boulevard du Souverain (E048973).

|

Fig. 7. Emile-Henri t’Serstevens, Parade in Auderghem, 1907-1911. Glass plate, 9×12 cm. Brussels: Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage. © KIK-IRPA, Brussels, E048968. |

Modern-day technologies and the large-scale online access to photographic collections facilitate such an approach. For example, the BALaT database made it possible to search in KIK-IRPA’s photo library by location. When the location of a photograph was successfully identified, the database often displayed more examples of the same city, providing a first clue in the identification of other – at this point still undetermined – places. The online mobile mapping service Google Street View also proved its usefulness: additional information allowing a more specific localization in, for example, parks and (small) streets was now possible.

Nonetheless, these methods also have their limits. Over the past century, cities have changed: new buildings have been constructed, older houses demolished and replaced by modern ones. A good example of such an urban transformation can be observed in Antwerp. The statue on the Teniersplaats, made by Joseph-Jacques Ducaju (1823-1891), was installed in 1867.[38] While the sculpture remained unchanged, the surrounding buildings changed significantly. (Fig. 8) Likewise in Oostende: the coastline underwent similar drastic changes. Although the photo taken from the Casino-Kursaal could easily be identified with the aid of an old postcard, Google Street View nowadays presents us with a completely different view. (Fig. 9) Whereas most important historic landmarks of big cities are still visible today, in the case of (small) villages, such reference elements are often lacking. Therefore, other methods are required to identify these sights. Even so, such an attempt – especially given the Internet’s user-friendliness – entails some risk. Often there are many similarities between images that are not necessarily linked. As a result, it is easy to be misled by these visual matches. A critical attitude, with more than one set of eyes and discussions with other experts, is thus indispensable.

À l’œuvre on connait l’artisan: looking for clues in finding the photographer

This verse by Jean de la Fontaine (1621-1695) inspired the methodology applied in identifying the collection’s author. The complete absence of data with respect to the photographer obliged us consider the collection as the primary source – both visual and material – in our search for information. It quickly became evident that we were dealing with a diverse collection of images: landscapes, portraits of humans and animals, events, family life, snapshots, carefully staged shots, etc. Topic-wise, a striking resemblance with what we commonly know as amateur collections, e.g. family albums, was observed. It became obvious that we were dealing with a collection that was not the product of any professional activity, but the legacy of an amateur photographer. Professional photographers worked in studios and had a standardized way of capturing, for example, architecture or people.[39]

Analysing each image individually as well as looking at the collection as a whole enabled us to recognize the environment in which the photographer carried out his activity. Relatively quickly, it became clear that our author belonged to both the intellectual and economic upper-middle class. Impressive and comfortable homes (E049028), refined coiffures and elegant clothing, upper-class sports activities such as tennis (E048100) and croquet (E048949), regular excursions around the country (fig. 10) and abroad (E049263), all attest to a certain level of financial comfort. Indeed, the very practice of photography – at this time still mainly done on glass plates – required a certain financial investment, as the shooting and processing materials were relatively expensive, while the execution of the medium demanded specific knowledge and skills. Besides professionals, the medium was therefore limited to the moneyed upper class who were privileged enough to afford such an expensive hobby.

|

Fig. 10. Emile-Henri t’Serstevens, On the Beach of Knokke, ca. 1900. Glass plate, 9×12 cm. Brussels: Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage. © KIK-IRPA, Brussels, E048075. |

Just as any family album gives us an idea of an entire family, including the photographer, the same applied to this collection. Likewise, the self-portrait is a recurring theme in the work of many photographers with artistic aspirations, whether amateur or an established artist. Two clues helped us in identifying the photographer. Firstly, one of the earliest photographs is a studio portrait of a young photographer posing proudly next to his camera. (Fig. 11) Secondly, given that the entire collection – including images that were less successful – had been preserved, it was possible to observe changes in the composition of group and family pictures. In each of the examples, we saw the appearance of a small moustached man (E048425, E048423) who bore a striking resemblance to the person in the aforementioned studio portrait. We were consequently able to conclude that this was the main author, who on several occasions lent out his camera to another individual in order to become part of the visual souvenir he was creating. This other person, in most cases, is a curvaceous dark-haired lady, presumably his wife. On occasion, a third person stepped in to photograph the couple (E048280). Looking at these photographs, it is interesting to remark that we are able to observe the couple in the process of ageing, as well as their personal history: weddings of family members and friends, pets growing up – the couple had at least six dogs, which they apparently viewed as their surrogate children – and new furry friends. All in all, almost thirty years in the life of the collection’s authors can be recreated by looking at these images!

|

Fig. 11. Anonymous, Portrait of the Photographer Emile-Henri t’Serstevens, 1890-1892. Glass plate, 18×13 cm. Brussels: Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage. © KIK-IRPA, Brussels, A144531. |

The quest for a name

Despite the amount of information extracted from the photographs and their visual identification, the fact remained that the authors were still formally unknown. Fortunately, the photographer left us – whether intentionally or not – with some clues that helped lead to his identification. Among the scraps of paper that were used as protective interleafs to separate the negatives, two letters are of great interest. The first is a standard invitation sent out by the festival committee of Nouvel Uccle to the president of an unspecified company for the ‘Grand Festival Sunday’ that was held on August 31, 1890. The letter is signed by both the president and the secretary of the festival committee: Paul De Fre[40] and E. t’Serstevens fils. The second piece of interesting correspondence is a fragment of a handwritten letter dated May 1, 1892 addressed to E. t’Serstevens residing at 99 avenue Brugmann, from the periodical Le Peuple, l’Echo du peuple, published by the socialist union in Brussels. This correspondence found amongst the negatives led us to believe that ‘E. t’Serstevens’ might perhaps be the name we were seeking. A recent publication on the genealogy of the family t’Serstevens, one of the oldest families of the Brussels region, allowed a definitive identification of some of the protagonists found in our photographs.[41] What is more, one of the negatives in the collection directly matched one of the illustrations used in this book. Based on this information, it was possible to formally identify the photographer as Emile-Henri t’Serstevens (1868-1933). Having obtained a PhD in Law at the University of Brussels (Université Libre de Bruxelles), t’Serstevens held the profession of notary in Saint-Gilles (Brussels)[42] between 1901 and 1929, a field in which he succeeded his father.[43] Being the illegitimate son of Ignace François Emile t’Serstevens (1834-1908) and Marie Therese Doperé (1841-1873), Emile-Henri was not recognized by his father until 1875. This was the year in which his father Ignace married Julienne Verdier (1858-1946), with whom he had five children: Romain (1876-1947), Georges (1878-?), Gaston (1880-1919), Lucile (1882-1842) and Albert (1885-1974), who was to become a prolific novel writer. The whole family is beautifully portrayed by t’Serstevens between 1890 and 1892 (A144530).

As a photographer, t’Serstevens became a full member of the Belgian Association of Photography (Association belge de photographie – ABP) in 1895.[44] His admission to the association was recommended by two of its prominent members, the photographers Marcel Vanderkindere (1865-1941) and Charles Puttemans (1850-1933). After 1896, t’Serstevens is no longer mentioned in the member list of the association, which led us to believe that he left the association as an active member in this year.[45] Nonetheless, the year 1896 seemed to be the year in which he enjoyed his membership the most. He participated in one of the association’s meetings on March 11, during which he presented his lauded photographs.[46] In addition, he also attended the general meeting later that year on August 12. His work was furthermore exhibited at the second photographic art exhibition organized by the ABP in Brussels from 4 to 9 April 1896.[47]

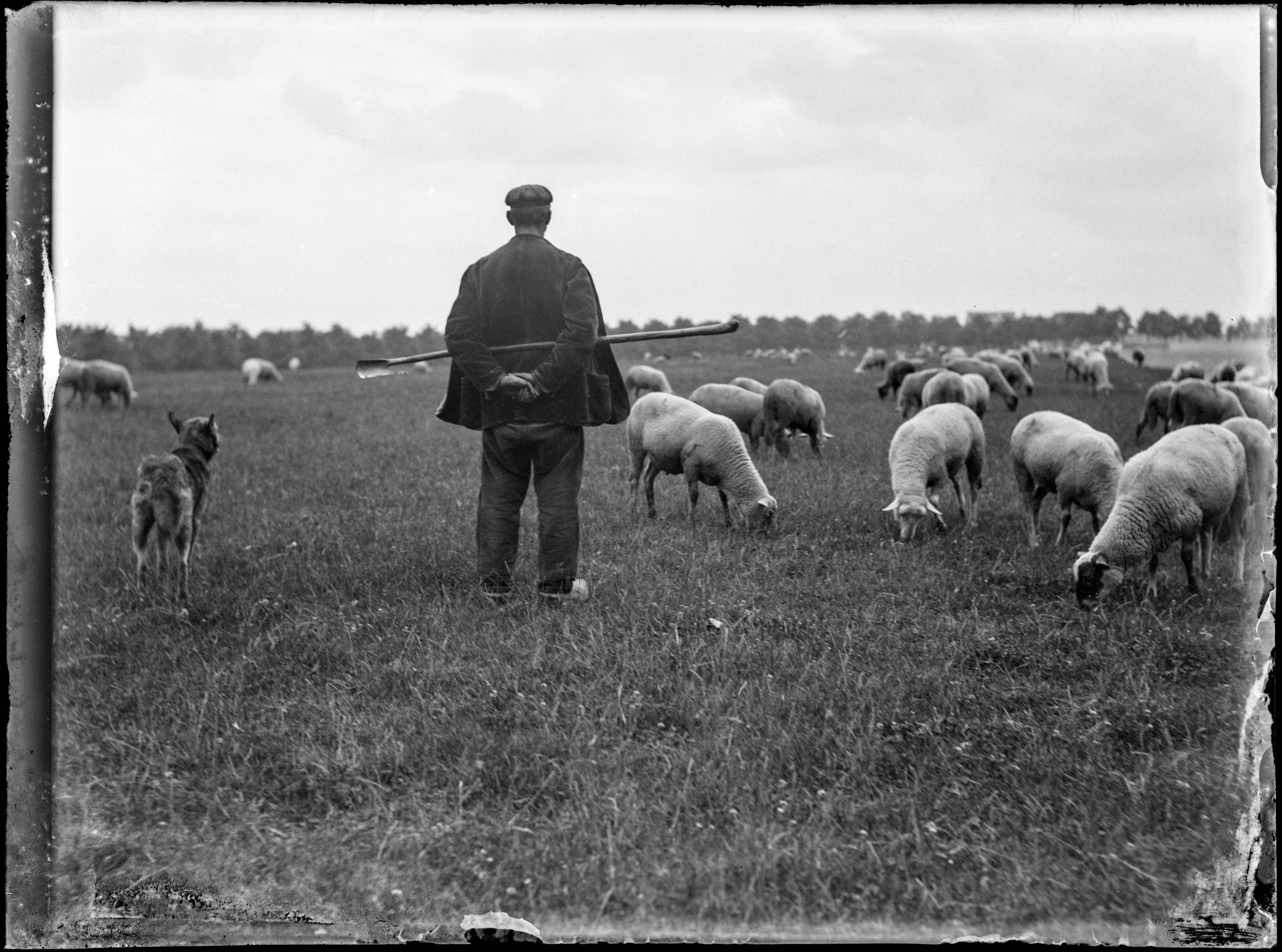

Although he was an effective member of the ABP, the fact remains that the photographs of t’Serstevens appear to deviate from the pictorialist language that was typical for the ABP, whose chief mission was to establish photography as a fine art by imitating the pictorial effects of painting.[48] While some correlations can be observed in the work of t’Serstevens and that of other Belgian pictorialists and the members of the ABP, e.g. his choice of subject (views of the countryside around Brussels, fields, etc.),[49] the way in which he treated his images – without any retouching – is different. For instance, compare At Sunset (1901), a photograph by his contemporary Léonard Misonne (1870-1949), one of the exponents of pictorial photography in Belgium, with a photograph displaying the same theme of a shepherd and sheep. (Fig. 12) The fact that t’Serstevens preferred a purer form of photography using only the medium’s own pictorial qualities, might have encouraged him to leave the ABP in 1897. Or perhaps he was excluded – if so, for what reason? Nevertheless, it is impossible to ascertain the reason(s) for his departure. Whatever the case may be, t’Serstevens went on to exhibit his photographs in 1904 and 1905.[50]

|

Fig. 12. Emile-Henri t’Serstevens, Sheep and Shepherd, 1890-1933. Glass plate, 9×12 cm. Brussels: Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage. © KIK-IRPA, Brussels, E048666. |

Besides landscape and cityscapes, t’Serstevens focused chiefly on portrait photography. Our research now enabled us to identify the people he immortalized on the light-sensitive surface of his glass plates. Among them, his wife Marie Dastot (1870-1943), who was herself active as a photographer, as her admission to the ABP as an associate member in 1896 suggests.[51] With most of t’Serstevens’ portraits, we could therefore assume that she is the other photographer. Also, we observed that she often assisted her husband in the handling of the family’s pets, which were used as models on occasion.

Re-establishing the author’s existence in the photo library

By the time the cataloguing of the collection was nearly completed, we realized that other pictures of t’Serstevens (about 400) had already been digitized and described. Unfortunately, they were not attributed to t’Serstevens, but instead to the name ‘Bommer’ – an indication that in previous times KIK-IRPA did not possess correct information regarding authorship. How did this erroneous information end up being linked to the photographs, and why were 75% of the supports never fully inventoried? What is the explanation for this encoding error, and especially, the undocumented division of the original collection? Dating the images before 1930 suggests that the collection was first acquired by the KMKG-MRAH, before being transferred, together with the photo library, to the ACL in 1948. Originally, the collection contained ca. 2000 negatives and was divided into two parts, with one part judged to be of interest to the photo library, and the remaining part simply put up for deselection.[52] Fortunately, these supports remained preserved and were also moved together with the rest of the collection to KIK-IRPA’s current building in 1962. While the 400 ‘lucky’ negatives were conserved in good condition, the other 1600 remained in hibernation. Immediately following their selection, a positive print of each of the 400 negatives that had made it into the collection was mounted on cardboard. On this mount, some basic information related to the image’s location and a date of origin was annotated.[53] By this time, the link with t’Serstevens had apparently already been lost, as the image’s provenance was annotated as ‘collection-verzameling Bommer’ – referring probably to Jules Bommer (1872-1950), the former curator at KMKG-MRAH, who also volunteered at the Service of the Belgian Documentation after his retirement in 1937. This could lead us to assume that the collection originally belonged to Bommer, or that t’Serstevens (or his family) asked Bommer to transfer the negatives to the KMKG-MRAH. All the same, when the analogue catalogue of the photo library entered the digital realm in the 1990s, Bommer was, as we now know, wrongly identified as the author of the images made by t’Serstevens and his wife.

For more than a half-century these two collections led separate lives, with the largest part – 1600 negatives – abandoned as orphans. Thanks to our research, we were able to reconnect these orphaned works with the proper metadata and to re-establish the correct author for the entire collection of 2,000 images. Undoubtedly, a further in-depth study of the collection ensemble will allow us to fill in other gaps in the metadata. Likewise, such a broadly oriented approach is certain to change our current idea of the style and quality of t’Serstevens photographic oeuvre. From an academic viewpoint, this emblematic case illustrates the highly problematic consequences when an undocumented division of a collection ensemble occurs. In this case, the portraits provide the clues for the photographer’s identification and a more accurate dating of, for example, city views and landscapes by using the ages of the portrayed as terminus post and ante quem.

A look into the photographer’s mind

Just as with paintings, photographs can be submitted to a formal analysis where the composition, the use of colour and contrast are discussed. Although photography initially adopted its pictorial language from the other two-dimensional arts, it also provided the author of the image with some technical tools that were unique. Although photography was seen as a simple reproduction of reality in its early stages, registering what fell within the picture frame still required a specific talent and attested to the unique vision of the photographer. Sharpness, contrast, the use of light and depth of field as well played an important role in determining the visual qualities of an image.

The style of the images and the choice of subject matter therefore provide us with insight into the author’s personality. The collection can roughly be divided into two sets: spontaneous pictures and photographs resulting from a true reflection on the part of the artist, e.g. the staging of the composition and the use of light. These two subsets are not tied to any one specific subject or type of photography. For example, so-called ‘snapshots’ as well as carefully orchestrated photographs can both be found among the portraits.

One photograph, which can best be described as a group portrait in a wood or park, shows four people standing along a path during the winter. (Fig. 13) Each person portrayed poses in a unique and elegant manner. The use of the portrait format, the appearance of the slender canes, top hats, and the leafless trees, all lend a strong vertical momentum to the image. Similarly, in another picture, the composition of the group is inspired by the natural forms of the landscape (E048341). The series, roughly entitled as en file indienne, meaning ‘positioned in a single row’, is also an illustration of the photographer’s meticulous reflection when arranging the image’s surface. In his search to find a strong visual composition, the photographer asked his models to vary their position slightly during the shoot. In the collection we found many examples of images that serve as evidence confirming that the photographer dedicated a substantial amount of time to create the desired images in fulfilment of his vision. The fact that he often used up entire packages of negatives for only one shooting session – despite the high cost of the glass plates – indicates that he maintained a high degree of perfection. (Fig. 14)

|

Fig. 13. Emile-Henri t’Serstevens, Group Portrait in a Wood, 1890-1900. Glass plate, 18×13 cm. Brussels: Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage. © KIK-IRPA, Brussels, A144463. |

Other images are defined by his chosen point of view, a determining factor in the composition. In Portrait de Romain t’Serstevens au Bois de la Cambre (A144509), the point of focus is the decisive factor in the arrangement of the image. t’Serstevens, after carefully choosing the background – a low-lying area and a sort of cave – used the outlines of the surroundings to give the scenery a ghostly appearance.

Certainly, the clever use of backlight best illustrates his artistic approach, such as in La forêt de Soignes (E048661), where the sunlight passing through the leaves renders the light almost tangible. While the blurred leaves and branches give the composition a dreamlike quality, the sharpness of the ground takes us back to reality and invites us to follow the path. In Coucher de soleil sur la mer du Nord (E048658), the people are photographed entirely in backlight. They are reduced to mere anonymous black silhouettes, thus creating a strong and timeless image. When composing his images, t’Serstevens paid significant attention to both the composition and the use of atmospheric light effects. The fact that he photographed the sunset numerous times affirms both his artistic aspiration and his ties with pictorial photography in terms of his choice of subject matter. (Fig. 15)

|

Fig. 15. Emile-Henri t’Serstevens, A Pond in Watermael-Boitsfort, 1890-1933. Glass plate, 9×12 cm. Brussels: Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage. © KIK-IRPA, Brussels, E048378. |

Unlike the work of the exponents of Pictorialism, however, most of his photographs reveal a great spontaneity. (Fig. 16) City views, mainly composed according to the horizontal landscape format, are often taken from a dynamic angle and occasionally from a worm’s eye view (E048493). The monumental static character of city architecture interested him only mildly, as opposed to his immediate urban environment (E048504). Furthermore, in most of his portraits – which are closely framed – the model does not look directly into the camera (E048874, A144613). Moreover, the person portrayed does not pose in a formal manner: instead, a natural and spontaneous posture and expression is preferred (E048531). Even when the location of each model is organised and planned, as in some group portraits, then their expression remains very personal, natural and spontaneous. (Fig. 17) Quite often, the setting and positioning of the model contradicts the traditional rules of composition in official portrait photography that have been acknowledged since Disderi.[54]

|

Fig. 16. Emile-Henri t’Serstevens, Family Portrait, 1890-1933. Glass plate, 9×12 cm. Brussels: Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage. © KIK-IRPA, Brussels, E048277. |

|

Fig. 17. Emile-Henri t’Serstevens, Group Portrait on the Tennis Court, ca. 1910. Glass plate, 9×12 cm. Brussels: Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage. © KIK-IRPA, Brussels, E048740. |

‘Ceux qui veulent sortir de cette pétrification doivent enfreindre le code dominant. Assis à califourchon sur une chaise, les pieds appuyés sur une table, assis en tailleur sur une colonne, portraiturés de dos, ils tentent d’échapper à l’uniformisation pour se réapproprier leur image, redéfinir leur identité.’[55]

Especially t’Serstevens’ group portraits often display a unique sense of humour and originality (E048937, E049710, E048565 and E049154).

To conclude this analysis, two observations are essential. Firstly, the prevalence of animals in t’Serstevens’ work is significant. Animal photography poses a technical and artistic challenge, as the success of the photo shoot greatly depends on the models’ cooperation (E048158, E048419). Secondly, t’Serstevens was not afraid to capture people in motion, using either a plate camera with glass negatives or a hand-held box camera with easy-to-use roll film. (Fig. 18) (E048751, E048334, E048991)

|

Fig. 18. Emile-Henri t’Serstevens, Boulevard des Capucines in Paris, 1890-1933. Glass plate, 9×12 cm. Brussels: Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage. © KIK-IRPA, Brussels, E049070. |

It is clear that t’Serstevens possessed an artistic vision that he wished to express. His membership in the ABP, whose main goal was to emancipate photography as a fine art, attests to the view that he saw himself as a true photographer and an artist. Although amateur photography has often – especially during the second half of the twentieth century – been considered to be of a mediocre, even inferior quality that was unworthy of the label ‘art’, the pictorial language of photography was in fact liberated by those who practiced it in this manner. It was the amateur photographers, unbound by any convention, who dared to experiment with the new angles and daring compositions that would ultimately establish photography as a unique form of art.

Many of these amateurs, whose focus was first and foremost directed towards documenting their own personal life, have been acknowledged for their artistic qualities. One example is the work of the French photographer Jacques Henri Lartigue (1894-1986). Like t’Serstevens, Lartigue was a bourgeois whose comfortable lifestyle allowed him to freely experiment with the medium. Although t’Serstevens turned to photography much earlier, there are some striking resemblances in the two men’s work. Despite his obvious artistic motivations, t’Serstevens’ photographs were originally selected because of their research value for the study of heritage. While the photo library’s chief purpose was, and still is, to create a collection of documentary and standardized photographs, an appreciation for the artistic qualities of these works is by no means the exception in the history of photography. Perhaps the best-known example is the work of Eugene Atget (1857-1927).[56] In the case of t’Serstevens, we can state that the circle is now complete, as he is finally recognized as a photographer.

An unintended glimpse into the life of other members of the Brussels bourgeoisie

Emile-Henri t’Serstevens immortalised his friends’ and relatives’ offspring, events, excursions, etc. In doing so, he provided us with an image of the daily life of the Brussels bourgeoisie between 1890 and 1920 that was unintended. Besides his wife and other members of the t’Serstevens family, we can also identify several other members of the photographer’s reputable circle of friends, including the composer Joseph Jongen (1873-1953) and the violinist Emile Chaumont (1878-1942).[57] Multiple photographs show a picture of t’Serstevens sitting in front of a harmonium,[58] which, thanks to the link with Joseph Jongen, could be identified as the Mazet Art-Harmonium that was used by the Scala Musicae of Brussels during several concerts from 1909 on.[59] The organ was the property of t’Serstevens, who, in this light, can be seen as a patron of the musical arts. That t’Serstevens and Jongen were good friends is also affirmed by Jongen’s organ composition Trois pieces pour Harmonium, which he ‘dedicated to his friend t’Serstevens in 1909’.[60] t’Serstevens was ‘prominent in musical circles’.[61] He is also likely to have had good contacts with composer and violinist Eugène Ysaÿe (1858-1931),[62] whom he photographed together with his wife, Louise Bourdau (1868-1965).[63]

Several pictures of painters, musicians, actors, and even comedians illustrate that t’Serstevens was a well-known figure in artistic circles. For example, the collection also provides us with some behind-the-scenes pictures of an amateur theatre company, the Jonge Toneelliefhebbers, active between 1880 and 1963.[64] A group picture (A144527) dating between 1890 and 1910 allows us to identify this troupe, whose motto was ‘Geen Rijker Kroon dan Eigen Schoon’ – which can be translated as ‘One is never better served than by himself’ – as can be read on the headpiece of one of its members. Several images documenting the creation of the decors perfectly illustrate the company’s idea of autonomy. For example, one picture (E048573) reveals the design process of the scenery: dioramas were made and pictures served as an inspiration for the decor. Another picture gives us a glimpse of the designs’ execution in actual size (E048843).

In addition to photographs of public figures that are unofficial and until recently unknown, it is clear that the photographs taken by t’Serstevens provide us with an inadvertent glimpse of everyday life at the turn of the century for the most fortunate members of Belgian society. He shows us luxurious interiors, champagne tastings, fashion, excursions to the coast and travels abroad. As such, he provides us with an uncensored image of the Brussels upper class. His images are therefore also a unique testimony of life in that era and can also be used for purposes other than the inevitable study of Belgian heritage.

A collection to remember

The t’Serstevens Collection provided the opportunity to establish a methodology in researching photographic collections with a high degree of disassociation. With the current transition from analogue to digital, as well was the rising interest in historic photographic collections, there are undoubtedly many such collections as yet to be discovered. Being confronted with similar collections, a step-by-step methodological approach is essential in maintaining an overview. Equally indispensable is the perception of the photograph as a material source, as this will help to identify some initial clues with respect to dating the pictures. Our research has proven that, even in cases were very little or no metadata is present, modern technologies and tools can help to restore collections of this sort to their status as cultural heritage, both in the digital world and beyond.

Similarly, this case study illustrates the importance of respecting collection ensembles as unique composites: it was only through observing the ensemble as a whole that essential metadata and contextual information could be retrieved. Notwithstanding the long time span since the disassociation, only now has it become possible, thanks to the current technological developments of digitization, to (re-) valorise the photographs. Today, this almost entirely forgotten collection indeed has a bright future.[65]

Bibliography

Exhibition catalogues

Album de la deuxième exposition d’art photographique à Bruxelles 1896, exh. cat. Brussels, Association belge de Photographie.

L’effort, cercle d’art photographique. Ve salon 1905, exh. cat. Brussels, Galerie Boute.

Troisième exposition d’art photographique 1896, exh. cat. Paris, Photo-Club de Paris. Available online: http://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/btv1b84583711/f3.zoom (accessed 10 December 2014).

Websites

Alamanachs du commerce et de l’Industrie de Bruxelles, http://www.bruxelles.be/artdet.cfm?id=6332&PAGEID=5070&startrow=31 (accessed 10 December 2014).

Belgian Art Links and Tools (BALaT), http://balat.kikirpa.be/search_photo.php (accessed 10 December 2014).

Delcampe International sprl, http://www.delcampe.net (accessed 10 December 2014).

Eugène Ysaÿe, http://ysaye.kbr.be/ (accessed 10 December 2014).

The Photographic Repertory, Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage, http://www.kikirpa.be/EN/105/335/Mobilier+des+sanctuaires.htm (accessed 10 December 2014).

CV

Hilke Arijs studied Audiovisual Techniques and obtained a Master’s degree in Art Sciences and Archaeology at the Vrije Universiteit Brussel (VUB). She has been working for the Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage (KIK-IRPA) since 2007, where she has coordinated several conservation and digitization campaigns and is responsible for the collection of photographic materials. Since 2008, she has been specializing in the preventive conservation of photographic, audio-visual and digital collections. She is a frequent speaker at international conferences and also actively teaches on this subject through ICCROM-courses, among others. Furthermore, she has been a member of several expert committees on digital preservation since 2012.↑

Elodie De Zutter graduated as Master in Art History and Archaeology specialized in museology and the conservation of moveable heritage in 2012 at the Université Libre de Bruxelles (ULB). Flemish painting of the XVth century has since been her main research topic. In 2012-2013, she worked as intern in the Documentation Department at KIK-IRPA thanks to a grant from the Inbev Baillet-Latour Funds, and subsequently as a teaching and research assistant for the courses on medieval art at the ULB. She currently works as an art historian in the digitization team of KIK-IRPA, where she has been specializing in the digitization and scientific research of historic photographic collections.↑

Jeroen Reyniers is an art historian and graduated as Advanced Master in Medieval and Renaissance Studies in 2013 (KU Leuven). Since January 2014, he has been involved in a digitization project at KIK-IRPA. Furthermore, he is junior researcher at the Illuminare-Centre for the Study of Medieval Art-KU Leuven, where he coordinates the relic shrine of Saint Odilia (Kerniel-Belgium) research project. His research topics and interests are focused primarily on thirteenth century panel painting, the Flemish Primitives and Belgian photography.↑

Notes

1. Ceulemans 2005, p. 65.↑

2. On the creation of KIK-IRPA, see: Masschelein-Kleiner 2000.↑

3. Piron 2012.↑

4. About KIK-IRPA’s photo library, see: Ceulemans 2005, pp. 65-70; Claes 2009 and Claes 2006, p. 18.↑

5. Van Goethem 1999, p. 21.↑

6. Arijs 2010, p. 139.↑

7. Alexander 1983, p. 166.↑

8. Loydreau 1857, p. 10.↑

9. Perego 1998.↑

10. Recht 2003, p. 6.↑

11. For more information about this type of photograph, see: Claes 2005. ↑

12. The extreme curling of the films is the result of the film composition. The earliest roll films did not possess an anti-halo or anti-curl layer (an extra layer of gelatin). As a result, these films have a high tendency to curl. This element also allowed us to date these films, as the anti-curl layer was only introduced after 1903.↑

13. A solution (1/99) of de-ionized or demineralized water and a wetting agent was used during a first application. Once the surface was clean, pure demineralized water was used to ‘rinse’ the surface so that there would be no residual wetting agent left.↑

14. The emulsion side was judged to be too fragile and susceptible to scratching for us to perform a direct cleaning method.↑

15. The PAT (Photographic Activity Test) is an international standard test (ISO18916) for evaluating the long-term innocuousness of photo-storage and display products. ↑

16. We chose not to flatten the supports, as this treatment is very labour-intensive and, in many cases, the supports tend to relapse into their curled-up state. ↑

17. The following requirements were established for the digital files: uncompressed TIFF v6.0. fileformat, 16 bit, ECIRGB colour space and a minimum of 350 ppi.↑

18. During the digitization process, the Flemish CEST-guidelines for the digitization of photographic supports were implemented.↑

19. With regards to the discussion of performing retouching treatments on digital images, see: Arijs 2012, p. 116.↑

20. Arijs 2012, p. 112.↑

21. Given the fact that in most documentary collections photographs were seen as mere reproducible carriers of image content, unidentifiable photographs were useless within such a viewpoint. Nowadays, however – and fortunately – more attention is paid to the material aspects of a photograph, acknowledging that each photograph is a unique piece.↑

22. To access the BALaT database: http://balat.kikirpa.be/search_photo.php . ↑

23. The Dublin Core Schema is the standard in order to make information retrievable online and uses 15 element sets (Title, Creator, Subject, Description, Publisher, Contributor, Date, Type, Format, Identifier, Source, Language, Relation, Coverage, Rights).↑

24. Valverde 2004, p. 15. ↑

25. Lavédrine 2008, p. 254. ↑

26. In 1883, they opened a filial in Görlitz, in 1888 in Brussels, and in 1888/89 in Melbourne. The organization in Berlin was located at 8 Johanniter-Strasse.↑

27. In the journal L’effort, the advertisement mentions that they were located in Boulevard du midi 9 and 20. See: L’effort, cercle d’art photographique. Ve salon, p. 7.↑

28. For example: ‘Fournitures Gles Pour la Photographie- Laboratoire à la disposition des clients, Téléphone 114, J. Marynen, 39 Montagne aux herbes Potagères, and ‘Maison Rodolphe’.↑

29. Two different advertisements are observed: 1) Exposition universelles Paris 1889-1900 Grands prix 2) Grands prix-Paris-1889-1900 hors concours, (membre du jury) St.-Louis (U.S.) 1904.For an interesting overview of these exhibitions, see: Bacha Myriam (2005).↑

30. In one specific case, the series of several group portraits could be dated thanks to the annotation groupes 1908 on the box.↑

31. The description ‘station Uccle Stalle’ made it possible to identify this cliché (A144469), but also the other example that was made at the same time, but which had been separated and placed in another box (A144548).↑

32. This combination of a letter and six numbers refers to the official negative number, which can be used to consult the image in the BALaT database.↑

33. Comparing the image content of several negatives with a captioned photograph – Auderghem (ferme des trois fontaines) – this building, which was initially impossible to locate, was identified as the Château de Trois-Fontaines or Dry Borren. The building, situated in the forest of Soignes close to the Rouge Cloître abbey in Auderghem, has its roots in the thirteenth century and stayed partly afloat. See: Maes 1976, pp. 3-5 and 29-33.↑

34. De Clercq 2004, pp. 50-2 and Meyfroots 2004, pp. 66-7.↑

36. Dietvorst 2001, pp. 23-5.↑

37. An example of an online platform for examining and buying postcards is: http://www.delcampe.net ↑

38. Van Ruyssevelt 2001, pp. 74-5.↑

39. Leenaerts 2012, pp. 1-2.↑

40. This person was perhaps a relative of the mayor of Uccle, Louis De Fré, who held this function until 1880.↑

41. De Fossa 2013.↑

42. His office was located at 82 Avenue de la Toison d’Or until 1909, after which it moved to Avenue Berckmans 122. See: Alamanachs du commerce et de l’Industrie de Bruxelles.↑

43. For his work as notary, Emile-Henri was awarded the title of chevalier de l’ordre de Léopold on July 20 1926. The study of Emile-Henri t’Serstevens in the archives of this order was conducted by Christelle Créteur, whose work we wish to acknowledge. ↑

44. Emile-Henri t’Serstevens is mentioned in the Directory of Photographers in Belgium 1839-1905 as a member of the ABP in 1896: Joseph et al. 1997, p. 374. Additionally, we tracked down his admission as early as 1895: s.n. 1895, p. 30. ↑

45. According to the Directory of Photographers in Belgium 1839-1905, another t’Serstevens belonged to the ABP between 1893 and 1905: Joseph et al. 1997, p. 374. He was selected to exhibit his photographs at the third exhibition of the Photo-Club de Paris in May 1896. See: Forestier 1896, p. 506 and the list of participants at the end of the exhibition catalogue. Troisième exposition d’art photographique (1896). About Gaston t’Serstevens (1861-1909), see: De Fossa 2013, pp. 302-5.↑

47. Album de la deuxième exposition d’art photographique à Bruxelles (1896). ↑

48. Bunnell 1994.↑

49. Berghmans 2010, p. 257.↑

50. Joseph et al. 1997, p. 374.↑

52. Those not selected: portraits, less standardized architectural photographs, multiple exposures, animals, etc.↑

53. These cartons were stamped with the annotation ‘Musées royaux du Cinquantenaire. Service photographique’, which indicates that the photographs entered the collection before the creation of ACL in 1948.↑

54. André Adolphe Eugène Disdéri (1819-1889), a Parisian photographer, developed the ‘carte-de-visite’ or ‘portrait-card’ format, which enjoyed an unprecedented success in the late 1850s.↑

55. Sagne 1994, p. 112. ↑

56. Nesbit 1994.↑

57. For a photograph of both musicians, see: Whiteley 1997, p. 21.↑

58. Images E048261, E048264 and E048267.↑

59. Whiteley 1997, p. 28. ↑

60. Whiteley 1997, pp. 161-62, 198. It was performed for the first time on 1-2 March 1909 in the Scola Musicae, 90 rue Gallait in Schaerbeek (Brussels). For the music score, with t’Serstevens name on the title: http://imslp.org/imglnks/usimg/f/f2/IMSLP284044-PMLP396590-Jongen__Joseph__3_Pi__ces_pour_harmonium.pdf (accessed 10 December 2014).↑

61. Quote from: Whiteley 1997, p. 240.↑

62. Ysaÿe was a renowned musician who gave Elisabeth queen of Belgium (1876-1965) instruction in playing the violin. Benoît-Jeannin 1989, p. 206 and De Jonge 2007, pp. 97-8. In 1937 she would introduce the first international competition of classical music: the Eugène Ysaÿe Competition. In 1951, this competition, originally conceived to promote the violin, would also be open to piano, and its name was changed into the Queen Elisabeth Music Competition, which still exists. S.n. 2001, pp. 1-7. For more about Eugène Ysaÿe, see the website created by the Royal Library of Belgium: http://ysaye.kbr.be/ . ↑

63. Images A144601, A144602 and A144603.↑

64. Quintens 1993, p. 95.↑

65. The authors would like to express their gratitude to the following persons for their help, advice and corrections: Christina Ceulemans, Christina Currie, and Erik Buelinckx. ↑

Publications

S.n. 1895, Bulletin de l’Association belge de photographie, vol. 22, no. 7, Brussels.

S.n. 1896, Bulletin de l’Association belge de photographie, vol. 23, no. 4, Brussels.

S.n. 1993, Le patrimoine monumental de la Belgique. Bruxelles, vol. 1B, pentagone E-M, Liège.

S.n. 2001, The Queen Elisabeth Competition of Belgium, 50 years of music theory/Le Concours Reine Elisabeth de Belgique, 50 ans d’histoire/De Koningin Elisabethwedstrijd van België, een halve eeuw muziekgeschiedenis, Brussels.

Edward P. Alexander 1983, Museum Masters: their Museums and their Influence, London.

Hilke Arijs 2012, ‘Documentaire foto’s en digitalisatie. Een blik op wat ooit onzichtbaar was’, in: Marjan Buyle (ed.), Het onzichtbare restaureren / Restaurer l’invisible, Proceedings of the BRK-APROA annual conference, Brussels 17-18 November 2011, Brussels, pp. 111-20.

Hilke Arijs 2010, ‘La photographie au service du patrimoine artistique’, in: Emmanuel Bodart et al. (eds.), Namur à l’heure allemande, 1914-1918: la vie des Namurois sous l’occupation, Namur, pp. 139-52.

Myriam Bacha 2005, Les expositions universelles à Paris de 1855 à 1937, Paris.

Maxime Benoît-Jeannin 1989, Ysaye. Le dernier Romantique ou le Sacre du Violin, Brussels.

Tamara Berghmans 2010, ‘Creating a Museum of Photography (1896): The collection Pictorialist Photographs of the Royal Museums of Art and History in Brussels’, in: Johan Swinnen et al. (eds.), The Weight of Photography. Photography History Theory and Criticism. Introductory Readings, Brussels, pp. 251-73.

Peter Bunnell 1994, ‘Pour une photographie moderne. Renouvellements du pictorialisme’, in: Michel Frizot (ed.), Nouvelle histoire de la photographie, Paris, pp. 310-27.

Christina Ceulemans 2005, ‘La photothèque de l’IRPA, un outil merveilleux pour tous les Belges’, in: Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage (ed.), Dynastie & Photographie, Brussels, pp. 65-70.

Marie-Christine Claes 2009, ‘Les fonds 1914-1918 dans la photothèque de l’Institut royal du Patrimoine artistique’, La France et la Belgique occupées (1914-1918). Regards croisés, Cahiers de l’IRHiS 7, pp. 8-13.

Marie-Christine Claes 2006, Les négatifs allemands de l’IRPA, 1917-1918, Brussels. Available online: http://www.kikirpa.be/uploads/files/ClichesAllemands.pdf (accessed 10 December 2014).

Marie-Christine Claes 2005, ‘Les « reportages » : un fonds méconnu de la photothèque de l’IRPA’, in: Royal Institute for Cultural Heritage (ed.), Dynastie & Photographie, Brussels, pp. 83-110.

Lode De Clercq 2004, ‘Représentations de l’église du XVe au XXe siècle et données historiques’, in: Direction des Monuments et des Sites (ed.), L’église Notre-Dame du Sablon, Brussels, pp. 50-2.

Christophe De Fossa 2013, La famille t’Serstevens. Une lignée d’orfèvres et d’imprimeurs bruxellois. Recueil de l’Office généalogique et héraldique de Belgique 66, Brussels.

Ralf De Jonge 2007, Koningin Elisabeth. Zwierige vorstin in woelige tijden, Antwerp.

Adrianus Gerardus Jozef Dietvorst 2001, Het toeristisch landschap tussen illusie en werkelijkheid, afscheidsrede, Wageningen, pp. 23-5. Available online: http://edepot.wur.nl/234684 (accessed 10 December 2014).

E. Forestier 1896, ‘Chronique. Exposition du Photo-Club de Paris’, Bulletin de l’Association belge de photographie, vol. 23, no. 7, pp. 500-6.

Steven F. Joseph et al. 1997, Directory of Photographers in Belgium 1839-1905, 2 vols., Antwerp/Rotterdam.

Bertrand Lavédrine 2008, (re)Connaître et conserver les photographies anciennes, Paris.

Danielle Leenaerts 2012, ‘Fotografische voorstellingen van Brussel rond de vorige eeuwwisseling (19e-20e eeuw): van documentatie tot artistieke expressie’, Brussels Studies 57, pp. 1-11. Available online: http://www.brusselsstudies.be/medias/publications/BruS57NL.pdf (accessed 10 December 2014).

Édouard Loydreau 1857, De la Photographie appliquée à l’Archéologie, Beaune.

A. Maes 1976, Trois-Fontaines. Une maison de chasse ducale en forêt de Soignes, Brussels.

Liliane Masschelein-Kleiner 2000, ‘Les cinquante ans de l’IRPA. Vijftig jaar KIK’, Bulletin de l’Institut royal du Patrimoine artistique 27, pp. 15-103.

Griet Meyfroots 2004, ‘La commission royale des monuments et la restauration de l’église aux XIXe et XXe siècles’, in: Direction des Monuments et des Sites (ed.), L’église Notre-Dame du Sablon, Brussels, pp. 58-69.

Molly Nesbit 1994, ‘Le photographe et l’histoire. Eugène Atget’, in: Michel Frizot (ed.), Nouvelle histoire de la photographie, Paris, pp. 398-409.

Elvire Perego 1998, ‘La ville-machine. Architecture et industrie’, in: Michel Frizot (ed.), Nouvelle histoire de la photographie, Paris, pp. 196-216.

Christophe Piron 2012, ‘Le rôle des services photographiques et du laboratoire des Musées royaux d’Art et d’Histoire dans la sauvegarde du patrimoine artistique belge durant la seconde guerre mondiale. Les raisons d’un succès, la genèse d’un institut’, Bulletin de l’Institut royal du Patrimoine artistique 33, pp. 257-87.

Patricia Quintens 1993, Toneel en Theaterleven te Brussel na 1830, Brussels.

Roland Recht 2003, ‘Histoire de l’art et photographie’, Revue de l’Art, vol. 141, no. 3, pp. 5-8.

Jean Sagne 1994, ‘Portraits en tout genre. L’atelier du photographe’, in: Michel Frizot (ed.), Nouvelle histoire de la photographie, Paris, pp. 102-22.

Maria Fernanda Valverde 2004, Photographic Negatives: Nature and Evolution of Processes, New York. Available online: https://www.imagepermanenceinstitute.org/webfm_send/302 (accessed 10 December 2014).

Herman Van Goethem 1999, Fotografie en realisme in de 19de eeuw. Antwerpen de oudste foto’s, 1847-1880, Antwerp.

Antoon Van Ruyssevelt 2001, Stadsbeelden Antwerpen anno 2001. Een gids-inventaris van de beelden en de monumenten, Antwerp.

John Scott Whiteley 1997, Joseph Jongen and His Organ Music, New York.