Reserved in Public but Extravagant in Domestic Circles: Fashion Photography from 1913 onward by Portrait Studio Merkelbach[1]

Abstract

The rise of fashion photography in the early twentieth century is currently receiving greater museum attention through an increasing number of exhibitions and catalogues. However, there is much that can be added to academic thinking and writing concerning this chapter of the history of photography. Recent research on the chic twentieth-century Portrait Studio Merkelbach in Amsterdam is an interesting case in this context. Its location on the floor immediately above the fashion house Hirsch & Cie – in its day a fashion sensation in the Dutch capital – brings one to the conclusion that Merkelbach profited from a flourishing practice of commercial fashion photography. Recent research into the newly digitized Merkelbach archives, as well as into Merkelbach’s vintage prints preserved in the collections of Leiden University, the Theater Institute and the Rijksmuseum in Amsterdam, and elsewhere, reveals an entirely different situation. At the same time, this research indicates that the historiography of fashion photography, in addition to visual communication in the public realm e.g. advertising in shopping windows and printed magazines, should as well include another theme: photographs that depict women presenting themselves in various clothes and outfits, taken specifically for private use and circulated among family and friends.

Article

Upstairs neighbor of an Amsterdam fashion house

Studio Merkelbach was initially a portrait studio, founded by Jacob Merkelbach in 1913 and continued by his daughter Mies Merkelbach as late as 1969.[2] Merkelbach was a leading studio in the Low Countries, renowned for its high quality staging, lighting and printing techniques, but also because Merkelbach himself profiled his work in pictorialist circles. In addition, he included his portraits in salons held both in the Netherlands and abroad. Finally, Merkelbach’s was a chic studio situated in the very heart of Amsterdam, receiving the patronage of the international beau monde that happened to be passing through the Dutch capital and wished to have their portraits taken, including members of the upper and even royal classes.

This article is aimed to report on this research, based on the notion that Studio Merkelbach developed a flourishing practice of fashion photography as well. Earlier publications have pointed out that there are at least a few fashion photographs taken by Merkelbach that still exist.[3]

Additionally, the photo studio was located in the very same building as the fashion house Hirsch & Cie: an upper-class fashion house that in its heyday was a real sensation in fashion-conscious Holland when the studio opened its doors on the floor directly above it.[4] (Figs. 1, 2) That Merkelbach would have developed a flourishing commercial practice of fashion photography with its successful downstairs neighbour seems quite plausible. Foreign photo studios in other European capitals, such as that of Madame d’Ora in Vienna, were doing so.[5] Jacob Merkelbach is certain to have known of examples of photo studios such as Madame d’Ora’s. In his younger years, he had been to Vienna, among other places, to learn his trade as a photographer. Moreover, his photography and manner of working reveal technical and stylistic similarities with those encountered at Madame d’Ora’s studio.[6] He must have seen the fashion photography of other photo studios in the magazines being circulated. Other circumstances stimulated this as well: women started to dress themselves more as individuals, according to their own taste and fashion, with lifestyle magazines to assist them in making choices as well emerging in those days.[7]

|

Fig. 1. Studio Merkelbach, Interior of fashion house Hirsch & Cie, Amsterdam, 1929, glass negative, Amsterdam City Archives, inv. no. MBCH00001000577. |

|

Fig. 2. Studio Merkelbach, Interior of fashion house Hirsch & Cie, Amsterdam, 1929, glass negative, Amsterdam City Archives, inv. no. MBCH00001000578. |

The recent digitization by the Amsterdam City Archives of tens of thousands of Merkelbach’s glass negatives, the digital matching of negatives to the studio’s administration, the online publication of an image base with the images and additional crowdsourcing in the years preceding this publication, revealed a treasure of new information on the practice of Studio Merkelbach.[8] The study of this archive in combination with researching collection prints and the relevant years of early popular Dutch fashion and life style magazines, however, have brought about a surprisingly different situation. Not only had there been little collaboration between Merkelbach and Hirsch & Cie, but in the administration and printed magazines, there was also very little work of his found that fits within the classical definition of fashion photography, i.e. photography that sells fashion.[9] Instead, another interesting type of fashion photography turned out to be hiding in Merkelbach’s archive: photography commissioned by private individuals for their own use, in which the portrayed persons – women in every case – dress up and present themselves in their various outfits, sometimes very extravagantly. This photography – circulated in private circles and not used to sell fashion – is certain to have had its own effect in terms of visually communicating fashion codes. I believe that it would be a good idea to include this type of photography in the definition of fashion photography as well.

As early as 1882, the fashion house Hirsch & Cie opened its doors on the Leidseplein in Amsterdam. It created a sensation. It was here that Dutch women of the upper classes – those who were able to permit themselves such extravagance – could be measured up for the latest Parisian haute couture, in a setting that was very ‘un-Dutch’, where they were treated with égard and addressed in the French language.[10] (Figs. 1, 2) In the very year of the fashion house’s opening, the national newspaper Algemeen Handelsblad announced to Hirsch’s competitors, who until then had largely offered German fashions, ‘Your reign is over! All that you have offered in the way of silk goods, velours and plush cashmeres, mantles and robes, furs and sorties has been overshadowed by the luxury and splendor of Amsterdam’s Maison Hirsch & Cie. Henceforth our women can experience in person the persuasiveness of the quality of the fabrics, the élégance and good taste of the clothing, coming from the original sources in Lyon and Paris.’[11]

Hirsch surprised the Dutch public time after time with innovations in the field of fashion. With the opening of its new building in 1912, it became the first fashion house in The Netherlands to introduce fashion shows featuring live models.[12] While some of the newspapers responded jubilantly, others were as yet unaccustomed to such an exotic phenomenon. Het Leven, for instance, wrote, ‘We have now seen them in Amsterdam too. […] Models strutting gracefully, chicly, affectedly, with studied precision…. in silence among the ranks of the ladies and gentlemen commenting upon and expressing their admiration, understanding nothing of what they hear, but still nevertheless wearing an “I-could-care-less-about-your-cackling” expression on their thickly powdered faces.’[13]

Fashion photographs for public use: the illustrated press

Judging on the basis of the lavish visual communication surrounding fashion that we know today, it appears that circumstances were perfect for Merkelbach to establish a flourishing practice in fashion photography. In addition to being located above the most trendy fashion house of his time, there were other favorable circumstances. The illustrated press was experiencing a major upsurge during this period. From the end of the nineteenth to the beginning of the twentieth century, there was a significant increase in both the size of press runs and the diversity of magazines for the general public.[14] Women were enjoying increased prosperity – this was true not only for the elite, but also for other layers of society.[15] The phenomenon of factory-made clothing was expanding.[16] Women were entering the stage of public life more frequently and were gaining distinction in a variety of social roles. All of these circumstances encouraged a consciousness of fashion experienced by a larger number of women. It likewise stimulated women to take a more conscious stance when purchasing fashion in order to distinguish themselves from others. In response to the greater supply of Parisian fashion, the ‘Netherlands Association for the Improvement of Women’s Apparel’ began promoting a critical attitude in 1899 in opposition to the ‘straitjacket’ of Parisian fashion – this was to be understood in a rather literal sense, as one of their main targets was the tight-laced corset – in favor of ‘reform’ clothing coming out of Germany. The audience for fashion photography grew. In July 1913, Het Leven published photos of the latest French fashions – which, true to tradition, had been launched at the horse races at Chantilly – under the title ‘The New Parisian Women’s Fashion’. In the following issue, the magazine’s editors noted ‘the desire expressed by our readers to have us devote a bit more, or a bit more often, attention to such subjects.’[17]

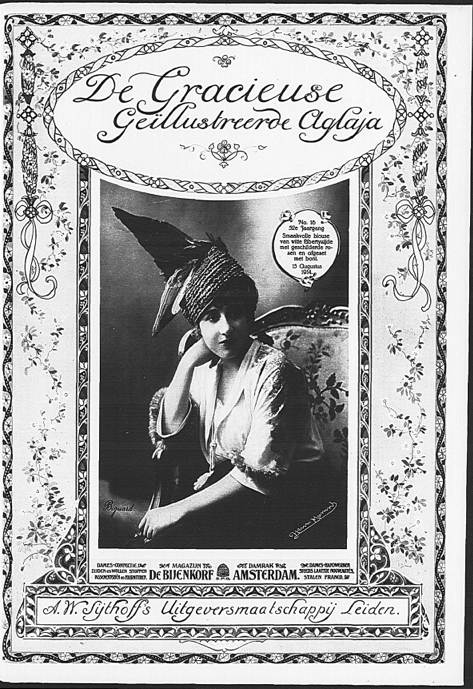

For many years, fashion drawing continued to dominate publications such as De Gracieuse. Geïllustreerde Aglaja, an important Dutch fashion and handicraft magazine for fashion-conscious women.[18] (Fig. 3) It was not until the first decade of the twentieth century that fashion photos began to appear on the covers of this magazine; even then, they were rarely found on its inside pages. In 1913 and 1914, photography was featured on the cover of De Gracieuse with even greater frequency, and by 1915, fashion photographs had elbowed out fashion drawings on the cover altogether. At this time, such fashion photos generally originated from outside the Netherlands – particularly Paris, e.g. the Talbot Studio and the studio of Henri Manuel.[19] (Fig. 4) Although photography was used to embellish De Gracieuse‘s covers, drawings remained in vogue when it came to depicting fashion on its inside pages. Photographs did appear on its pages for advertising other items, such as elastic stockings or ‘Weck’s preserves’.[20] In 1916, De Gracieuse features a series of advertisements in which Hirsch promotes his fashion wear by incorporating photographs of ‘new models of feather boas’, ‘Modern ruches and jabots’, and ‘Ornamental accessories’. These images reflect a kind of ‘useful photography’ that Merkelbach also produced. Haute couture, however, was not advertised yet with photography: Hirsch and other fashion houses continued to prefer drawings. [21] (Fig. 5) This was entirely in keeping with the custom of fashion houses such as Hirsch, Gerzon, and Metz, which all still worked with fashion drawings in their catalogues.[22]

|

Fig. 3. Artist unknown, Fashion drawing on the cover of Dutch fashion magazine De Gracieuse, 51 (1 July 1913) 13, p. 1. |

|

Fig. 4. Henri Manuel (Paris), fashion photograph on the cover of Dutch fashion magazine De Gracieuse, 52 (15 August 1914) 16, p. 1. |

|

Fig. 5. Advertisement with fashion drawings of fashion house Hirsch & Cie, Amsterdam, in Dutch newspaper Algemeen Handelsblad, 22 February 1938. |

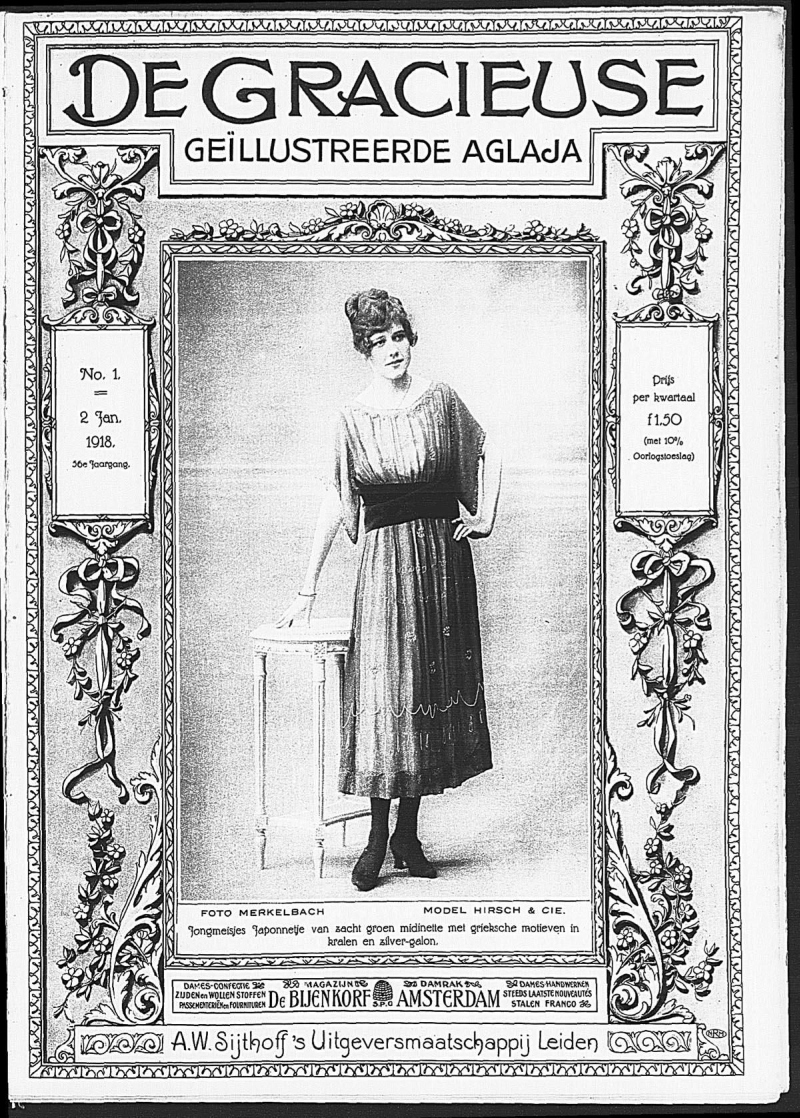

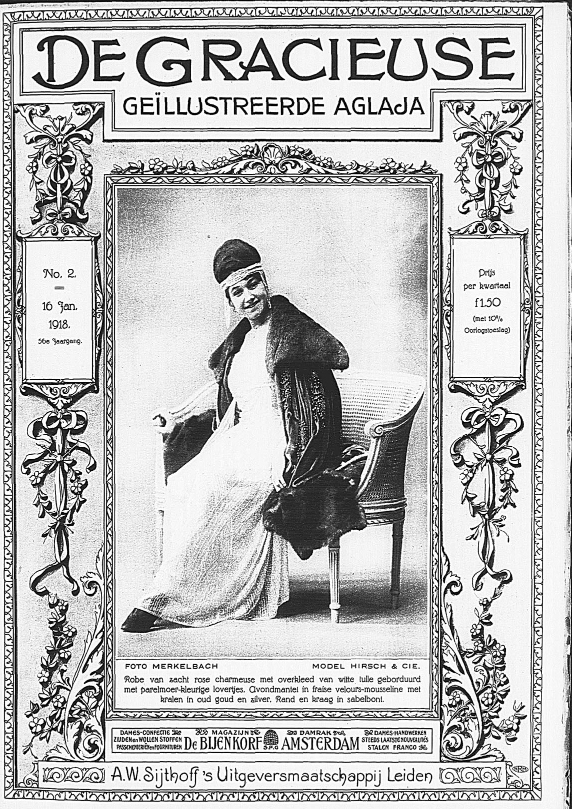

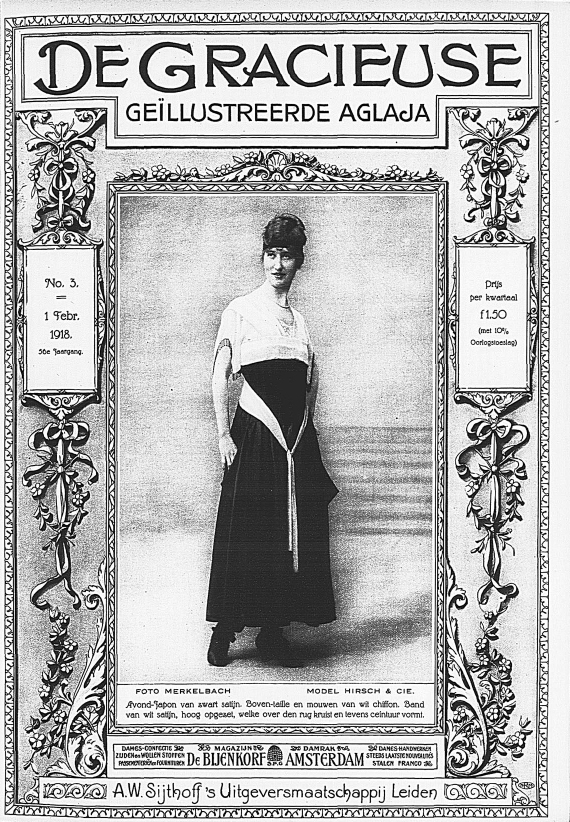

On those occasions when Hirsch did provide fashion photos for De Gracieuse , it was by no means a given that Merkelbach was the photographer. According to his account books of April 1915, Hirsch had already been a client of Jacob Merkelbach for two years. But when – in that very same month – photos of Hirsch & Cie’s fashion wear appeared for the first time in two successive issues of De Gracieuse, they were not taken by Merkelbach, but instead by the Amsterdam photographer Bernard Eilers.[23] It was not until the final year of World War I (1918) that the apparently obvious triangle of ‘Hirsch – Merkelbach – illustrated media’ finally seemed to take off. (Figs. 6, 7, 8) In January and February of this year, a fashion photograph taken by Merkelbach appeared on the cover of De Gracieuse that featured one of Hirsch’s models. [24] This collaboration, however, was soon over. Merkelbach’s following fashion photo was commissioned by the Gerzon fashion house, which appeared on the 1 May 1918 cover of De Gracieuse.[25] (Fig. 9)

|

Fig. 6. Fashion photograph by Studio Merkelbach, on the cover of De Gracieuse, 56 (2 January 1918) 1, p. 1. |

|

Fig. 7. Fashion photograph by Studio Merkelbach, on the cover of De Gracieuse, 56 (16 January 1918) 2, p. 1. |

|

Fig. 8. Fashion photograph by Studio Merkelbach, on the cover of De Gracieuse, 56 (1 February 1918) 3, p. 1. |

Fashion photography was also scarce in other Dutch mass circulation magazines, and when fashion photos did appear, they generally came from foreign photo studios, especially from Paris, Berlin and Vienna. Merkelbach, it seems, had no more success at breaking through this foreign ‘hegemony’ than any other Dutch photographer. Apart from the example of Bernard Eilers mentioned above, the names of other Dutch studios, e.g. photo studio Rembrandt in The Hague, appear only a handful of times.[26]

In the same period, the women’s magazine De vrouw en haar huis also covered women’s fashion and as well employed photography to do so – but likewise appears to have turned to someone other than Merkelbach. De vrouw en haar huis was oriented more towards the socially conscious woman versus the chic and extravagant De Gracieuse. Amidst its articles on topics such as women writers, women with interesting societal roles, the conditions in orphanages, and instructions for knitting balaclava for the soldiers in the trenches, De vrouw en haar huis also devoted attention to fashion. As opposed to the Parisian nouveautés in De Gracieuse, it frequently depicted decorative motifs from various countries as an art form through which Dutch women could express themselves.[27] While it is true that many of the fashion photos featured in De vrouw en haar huis were published anonymously, Merkelbach’s role appears to have been limited solely to that of a portraitist, as demonstrated by the portrait of Alida Wilhelmina Franciska van Korlaar-Van Dam, a Dutch author.[28]

In Panorama and Het Leven, one also encounters fashion photos published anonymously, with Merkelbach appearing to be a portraitist. In both of these magazines, however, there are no fashion photos that can be directly attributed to him by name. In the bookkeeping of Studio Merkelbach, the magazine Het Leven is stated as a client in the years 1917 through 1922. Fashion photos produced for Het Leven from 1917 and 1919 that we encounter in the negative archive, however, are nowhere to be found the printed magazine. It would appear that the editors rejected them. Notwithstanding, a portrait of the journalist J.H. Rössing in Het Leven Merkelbach is explicitly identified as ‘our portrait contributor’.[29] For its time, the magazine Panorama was extensively illustrated, as well in the area of fashion. It included a regular feature with fashion photos, which, it should be noted, were always published without any credit to the photographer. The first issue of Panorama ran a rather extensive article about Studio Merkelbach, with eight photos in total. Two of the photos were portraits of fashionably dressed actresses.[30] Outside its promotion as a portrait studio, nowhere do we encounter Merkelbach as a fashion photographer.

Fashion photographs for shop windows: indecent exposure?

Could fashion houses possibly have used photographs in their storefront windows in the same large formats that were employed by Merkelbach – varying from 24 x 18 cm to 50 x 40 cm – in order to give the passer-by a more vivid impression of their clothing on display? Merkelbach himself placed photos in his shop window on the Leidseplein to promote his portrait practice.[31] A photograph by Bernard Eilers from around 1921 shows a framed image in a Hirsch display window. Unfortunately, it cannot be determined whether this is a drawing, print or photo. If photographs were used in such a manner in storefront windows, they were certainly not portraits of random members of Hirsch & Cie’s clientele. It was regarded as unseemly for a lady of social standing to model and promote clothing publicly. ‘For that, there were artist’s models and […] girls off the street,’ as Mies Merkelbach explained, who, incidentally, did not share the same opinion herself.[32] This was the case not only in The Netherlands, but in the second decade of the previous century as well in Paris and New York, where the model Lillian Farly experienced the same sentiment.[33] Furthermore, some shopkeepers at the time were known to regularly place photos of customers in their shop windows that were seriously in arrears. This was one additional reason why private individuals would not have wished to be exposed in this context.[34]

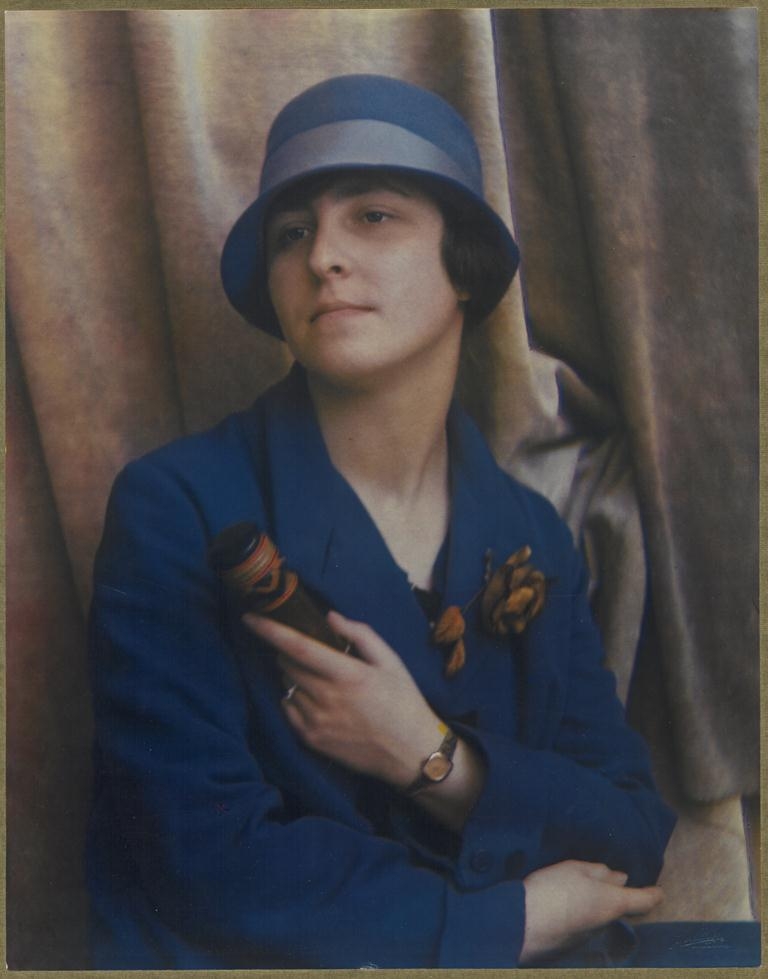

Merkelbach avoided objections to ‘indecent exposure’ of this nature on the part of private individuals, in part by working with professional live mannequins employed by Hirsch & Cie. From the year that that he first opened his photo studio, we find records of a ‘Miss’ Barends from Hirsch clothing posing for photos.[35] Beginning in the 1920s, Merkelbach regularly worked together with Aletta (or ‘Letty’) van Wijk, as seen in photos from 1924. (Figs. 10, 11) With Miss Barends, one can see how the compositions, image construction with backgrounds, and scenic props are all derived from the static formulas of portrait painting.[36] The model’s turned pose – in other cases with the hips slightly bent and arms raised in order to show off the body most favorably – can be traced back to those found in fashion drawing.[37] In a number of studies with Letty van Wijk, in which Merkelbach approaches the model more closely by depicting her half-length, it would appear he arrives at a formula that is more free and intimate. Here the distinction with portrait studies becomes incredibly thin. Moreover, Letty’s transparent clothing raises the issue of whether these photos were also intended for public consumption. (Fig. 12)

|

Fig. 10. Studio Merkelbach, Letty van Wijk, 1924, Jos-Pé colour process, 25,4 x 21,9 cm, Leiden University Library, inv. no. PK-F-61.1022. |

|

Fig. 11. Studio Merkelbach, Letty van Wijk, 1924, carbon print, 60,0 x 49,4 cm, Leiden University Library, inv. no. PK-F-71.280. |

|

Fig. 12. Studio Merkelbach, Letty van Wijk, 1924, glass negative, Amsterdam City Archives, inv. no. 010164020741. |

In addition to professional models, we also find actresses posing in Merkelbach’s fashion photos. The performance aspect of their profession allowed the public display of such fashion photos. In general, the theatre world was an important factor in the dissemination of fashion images. Inspired by the Parisian situation, Hirsch adopted the custom of introducing new fashion into the theatre: actors and actresses appeared in costumes originating from the fashion house.[38] Portraits of actors and actresses in this clothing were distributed for PR purposes among their fans as individual photos in cabinet card format.[39] With Merkelbach, we find only the faintest trace of such a practice: for one photo of Mrs Brandes in a theatrical costume, the Merkelbach archive includes the annotation ‘6 postcards’.[40] Merkelbach, however, generally worked in larger sizes.

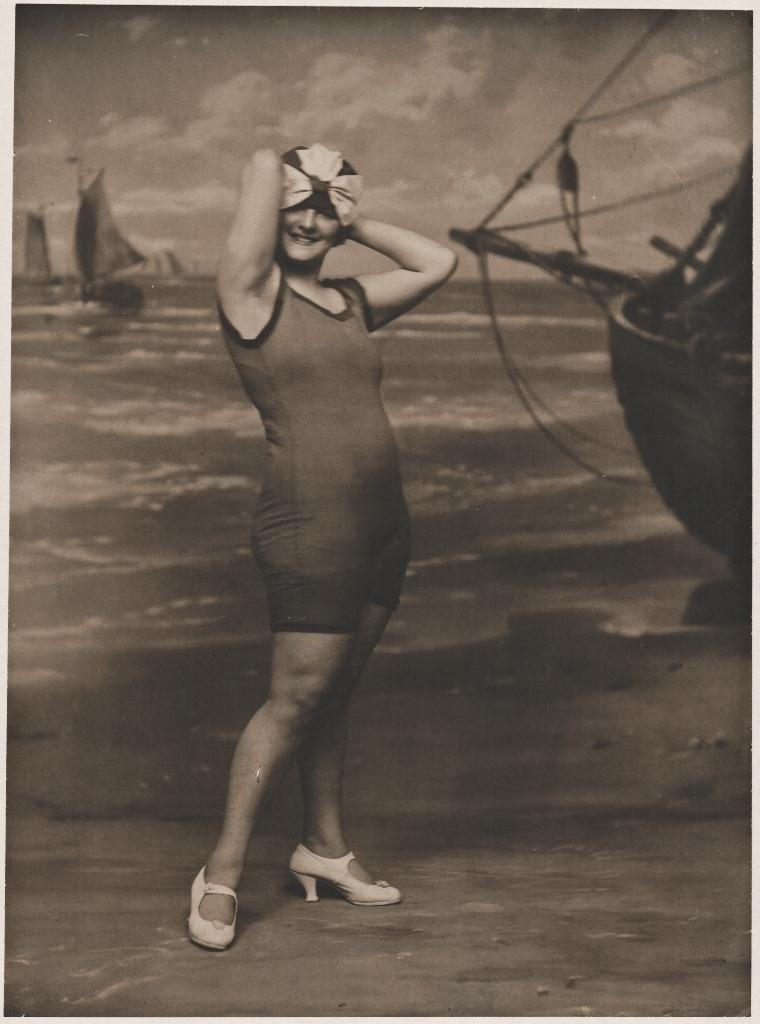

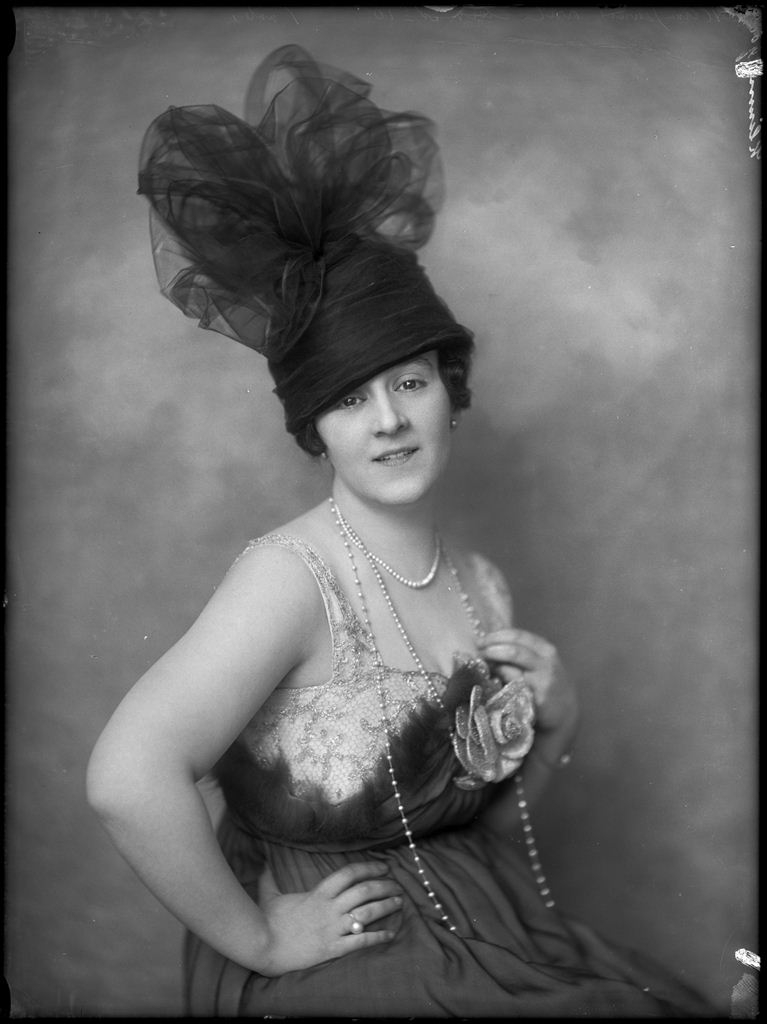

Photos of actors and actresses in fashionable clothing were also published in magazines like Cinema en Theater and Het Tooneel. Both magazines also devoted pages exclusively to fashion, as Cinema en Theater did in 1921, when it commissioned Studio Merkelbach to produce photos of swimwear.[41] (Fig. 13) This latter periodical also ordered photographs of the actresses Mientje Gosschalk and Greta Gijswijt from Merkelbach in clothing from Hirsch & Cie. The actress and singer Lola Cornero appears in dozens of Merkelbach’s photos. (Fig. 14) According to Merkelbach’s business records, she herself was the one to have the photographs commissioned. The question then arises: would she have handled her own public relations this actively? It appears that she wanted to have herself depicted in a more modern setting, against a stark white background, with a tunic over her dress, reminiscent of the Wiener Werkstätte.

Apparently, Merkelbach himself did not think it was improper for women to model clothing. Photos of his daughters Jo and Mies in fashionable clothing were shown in his display window on the street side of the Hirsch Building. (Fig. 15) After 1924, Mies was continually at her father’s studio, as she worked for him as a retoucher. Over the years, she also assumed the role of a model with a great deal of verve on hundreds of occasions. For instance, in photos from around 1924, we see Mies posing in a luxurious fur , a beautiful blue raincoat, a glamorous evening dress, and various fashionable hats. (Fig. 16) Just as in his portraits of Letty van Wijk from the same period, in the portraits of Mies, the photographer experimented with greater intimacy by depicting her half- length. In the case of Letty van Wijk, this led to an erotic undertone, while the portraits of Mies taken in the same manner bear witness to a father’s affection. The older man appears to have been very satisfied with one particular photo of Mies in a hat and wearing a light colored evening gown with a fur piece wrapped around the shoulders. (Fig. 17) He printed this portrait in various forms and formats, including a costly and time-consuming carbon print with the dimensions 40 by 50 centimeters.[42] He submitted it to an exhibition, and as the label on the back indicates, the photo graced a photo salon held in Bandung, a city in the Dutch East Indies, in 1925. In addition to these in-house projects, Mies also posed for a number of advertising commissions, which would continue to be a staple of Merkelbach’s practice from the 1920s onwards. We see her, for instance, appearing in fashion photos for the Delana fashion stores in Amsterdam, and in photos taken for the Amsterdam goldsmith Reggers, in which she poses with jewelry.

|

Fig. 15. Studio Merkelbach, Jo and Mies Merkelbach, between 1919 and 1929, carbon print, 52,4 x 44,7 cm, Leiden University Library, inv. no. PK-F-61.1019. |

Stylistic change over the years

In these photos, but also in Merkelbach’s fashion photography in which other models posed – such as those commissioned by the couturière Kruysveldt-de Mare – over the course of the years we see a more modern vision appear. (Fig. 18) It is no longer portrait painting or fashion drawing of the past that serve as the primary source of inspiration, but more modern forms of portrait and fashion photography that were reaching the Netherlands from abroad, and which were also being adopted by Merkelbach’s Dutch competitors, including Godfried de Groot.[43]

|

Fig. 18. Studio Merkelbach, according to administration: Kruysveldt – de Mare, 1937, glass negative, Amsterdam City Archives, inv. no. 010164033396. |

As the years passed, backgrounds that were more abstract in form, suggesting beams of light or movement, began to appear in Studio Merkelbach’s fashion photos. These are also reminiscent of foreign examples with more modernistic forms of fashion photography, e.g. such as produced by Edward Steichen. With the artificial light that Merkelbach began to employ in the 1930s, he – like other photographers – introduced a more dramatic use of contrast and shadow effects. Hirsch & Cie remained a client, albeit with less frequency. In a series on corsets, done on commission for Hirsch, one can see how Studio Merkelbach’s style evolved. The composition and use of light are inspired by modernism in photography. The body in the corset is treated as a sculptural form, with the artificial light creating a surprising effect as well as solid contrasts between the light and dark areas. The diagonals and curves of the shadows on the female body define the composition. A comparison of the photo of a women’s suit dating from the years of World War II with earlier photos, such as those of Miss Barends or Mrs Blöch, reveals a world of difference. (Fig. 19) The practical styling of the suit and the natural hairstyle demonstrate the degree to which fashion had changed; the sober background and the backlighting that creates the graphic effects betray the influence of New Photography. The only visual reminder of bygone days when the photo studio was richly decorated with tapestries is the carpet on which the model stands. (Fig. 20)

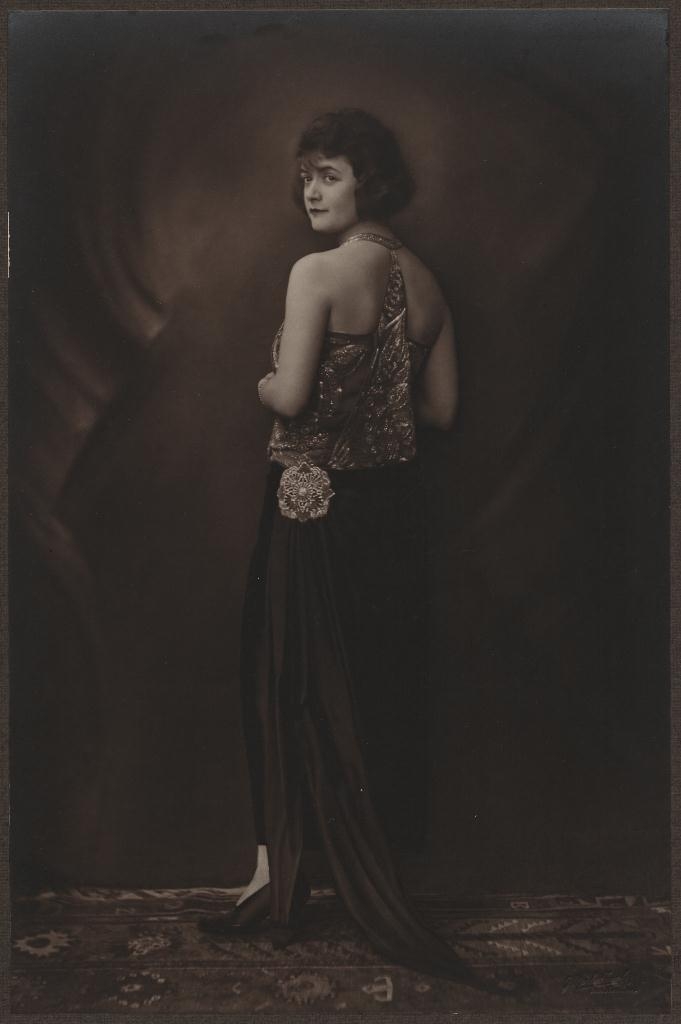

Fashion photographs for private use: a display of outfits

Considering Merkelbach’s archive and the early lifestyle magazines in assessing Studio Merkelbach’s production, the answer to the question of whether he ever developed his fashion photography to a level of intensity comparable to that of Studio Madame d’Ora – thereby taking advantage of being located so close to Hirsch & Cie – is a resounding ‘no’. In fact, there seems to have been little collaboration between the photo studio and its neighboring fashion house. Furthermore, there is very little fashion photography by Merkelbach found in Dutch magazines. At the same time, research into the archive of Studio Merkelbach reveals an abundance of a different kind of photographic communication with regards to fashion: the private portrait in which (primarily) women dress up and model their clothing. (Figs. 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27) Based on the rich visual communication of fashion photography in the twenty-first century, we are inclined to think of fashion photography primarily as a form of photography that is published and distributed in the public domain by the illustrated press. However, the accepted 1978 Hall-Duncan definition of fashion photography – photography produced to display or sell clothing or accessories – as well includes photography made for and distributed within the private domain.[44] It is in this realm that Studio Merkelbach did work that is both interesting and relevant to the history of fashion photography in the Netherlands.

In this context, the distinction between a fashion photo – a photo in which the display of the clothing is the main concern – and a portrait photo – a photo in which the identity of the person depicted is primary – is a question of emphasis and nuance.[45] Anyone sitting for a portrait is allowing himself or herself to be recorded for posterity in clothing that says something about his or her identity. This has been the case throughout the ages, and applies as much to historical painting as to photography. There are photographs, however, in which the attire is given the leading role. Take the magnificent afternoon dress of Mrs Blöch, from Amsterdam’s chic Vossiusstraat. She displays her wealth through the opulence of her gown. The beautiful afternoon dress worn by Mrs Thora van Loon-Egidius, a prominent resident of Amsterdam contributes to the visualization of her social standing and refined taste. (Fig. 21) In these portraits, one’s attention shifts from the face to the striking clothing, which makes up a great deal of the photograph. The women have apparently chosen quite consciously to have themselves depicted full-length. Mrs Marks likewise has her portrait done in three-quarter length wearing stunning clothing, with a photograph of a fashionable woman in the background, as if in an attempt to emphasize her own fashionableness.

|

Fig. 21. Studio Merkelbach, Mrs Thora van Loon-Egidius (1865-1945), Keizersgracht, Amsterdam, 1914, glass negative, Amsterdam City Archives, inv. no. 010164019800. |

The mysterious Mrs Klimm is an interesting case. In eight photos (as indicated by the negative numbers) that were taken in one session, Mrs Klimm dresses in a wide array of outfits. (Figs. 22, 23) She is an extravagant feast for the eyes, particularly when compared with the photos taken by Jacob Merkelbach that appeared in 1918 on the covers of De Gracieuse. The cover of this lady’s fashion magazine might perhaps appear as a top location, allowing one to excel at that moment in fashion photography. In reality, however, photos that were relatively respectable and static, shot in the tradition of portrait art and fashion drawing, were still considered more suitable.[46] (Fig. 6) According to Merkelbach’s business records, Mrs Klimm was staying at the exclusive Amstel Hotel. Apparently, there were more of these enterprising women who came to Amsterdam for longer or shorter periods at this time.

|

Fig. 22. Studio Merkelbach, Mrs Klimm (Amstel Hotel/Luijkenstraat 41, Jan/Weteringschans 13, Amsterdam), 1917, glass negative, Amsterdam City Archives, inv. no. 010164018860. |

|

Fig. 23. Studio Merkelbach, Mrs Klimm (Amstel Hotel/Luijkenstraat 41, Jan/Weteringschans 13, Amsterdam), 1917, glass negative, Amsterdam City Archives, inv. no. 010164018861. |

Mrs Sutterlui, for instance, settled in Amsterdam after the World War I.[47] (Fig. 24) Just as the actress Lola Cornero, and Mrs Klimm, she had herself photographed in all sorts of clothing and poses during various photo sessions. Mrs Brandes also had herself photographed in a variety of ways: close-up, smiling into the camera, in profile, full-length, and in extravagant theatrical costumes in which she appears to be performing a role in a play. (Figs. 25, 26) She gives the impression that she was very much in control of her own self-image. The women visibly enjoyed these photo shoots. It makes one wonder how things actually went in the studio: would they have shared their pleasure with Jacob Merkelbach? Or would he have accepted the feminine displays with a sigh? In any case, the playful fantasies of these women appears to have inspired Merkelbach to diverge slightly from the somewhat stiff compositions employed by him in other contexts during this same period.

|

Fig. 24. Studio Merkelbach, Mrs Sutterlui, 1923, gelatin silver print, 22,9 x 15,0 cm, Leiden University Library, inv. no. PK-F-69.525. |

|

Fig. 25. Studio Merkelbach, Mevrouw Brandes, 1919, glass negative, Amsterdam City Archives, inv. no. 010164019511. |

|

Fig. 26. Studio Merkelbach, [Woman in evening dress; Mrs Brandes], 1913, gelatin silver print, 22,8 x 12,5 cm, Leiden University Library, inv. no. PK-F-69.507. |

|

Fig. 27. Studio Merkelbach, [Portrait of an unknown woman], between 1919 and 1929, Jos-Pé colour process, 27,6 x 21,7 cm, Leiden University Library, inv. no. PK-F-61.1026. |

Merkelbach’s location above Hirsch raises the question of whether these women paid visits to the top floor to have their portraits taken, immediately after having purchased their new attire. The answer to this question is apparently no. This has to do with the way in which Hirsch sold and delivered couture. After a woman had chosen and ordered an item of clothing, she was expected to return several times for fittings. When the tailor-made result was ready, it was delivered to the customer’s home by a representative of Hirsch – even if it involved a trip to the provinces.[48] In all likelihood, women would have made a separate trip to have their portraits taken at the photo studio, selecting in advance the appropriate pieces of clothing to take with them to the studio, in order to dress up and pose in various manners following their arrival.

Conclusion

When Jacob Merkelbach began his photo studio, all ingredients for a flourishing practice in the field of fashion photography for print media appear to have been present. He occupied premises on a floor above the luxurious fashion palace of Hirsch & Cie; the illustrated press was experiencing an upsurge; women were entering public life; a larger number of women were starting to purchase fashion, and that in a more conscious manner. Research into Studio Merkelbach’s archive and a number of women’s and life style magazines published in the Netherlands from the 1910s through the early 1920s, however, reveals that photographic assignments commissioned by fashion houses or magazine publishers and intended for public consumption were rare in Merkelbach’s practice. The studio’s archive instead draws our attention to portraits in which women – sometimes involving elaborate photo sessions – are seen modelling their clothing in front of the camera and attired in various ways, apparently according to their own personal dictate. These photographs were commissioned privately and intended for viewing in private circles. When considered alongside photography published solely on a commercial basis in the public realm, they can be interpreted as an intriguing new facet to be included in discussions of fashion photography,

CV

Maartje van den Heuvel is art historian, curator of photography at Leiden University Library’s Special Collections, and PhD researcher in art history at Leiden University.↑

Notes

1. This article emerged in the framework of the exhibition Studio Merkelbach : Portraits 1913 -1969 in the Amsterdam City Archives, 13 September 2013 through 5 January 2014 and overlaps with Maartje van den Heuvel/Anneke van Veen, ‘Le bonheur des dames. Fotostudio Merkelbach en de mode’, in: Veen 2013, pp. 115-155. A special thanks to Anneke van Veen, Madelief Hohé and Annelies Kooijman for their input to this article.↑

3. Hegeman/Leijerzapf 1985 mentioned the publication by Dutch fashion magazine De Gracieuse.↑

4. Grijpma 1999.↑

5. See Faber 1983.↑

6. Hegeman/Leijerzapf 1985. The retouching and finishing in paper folders of Merkelbach’s photographs in de photo collection of Leiden University shows similarities to photographs by Studio Madame d’Ora in the collection of the Albertina, for example – as observed during a working visit to the Albertina photo collection, 19 February 2013. ↑

7. For women and their changing clothing behaviour in the Netherlands, see Leeuw, 1991. For the rise of the Dutch lifestyle and the fashion-illustrated press, see Delft 2006 and Delhaye 2008. Bommel 2012 writes on the rise of fashion photography in the Netherlands. ↑

8. The archive is said to have once been comprised of around 150.000 negatives. Currently, in the Amsterdam City Archives, 36.000 negatives remain; Veen 2013, p. 293, note 82.↑

9. Hall-Duncan 1978, p. 9.↑

10. Weijl 1966, 3. Until the beginning of the twentieth century, the pursuit of, and certainly the purchasing and wearing, of fashion was something reserved for the elite. Dekker et al. 2007, pp. 78-88.↑

11. Nijenhuis/Meij 2002, p. 91.↑

12. Dekker 2007, p. 85.↑

13. Het Leven, 7 (26 November 1912), p. 1526. Other magazines received even more enthusiastic responses; see for instance the citation from De Wereld in Dekker et al. 2007, p. 85.↑

14. Delft et al. 2006, pp. 8-9.↑

15. As is described for the British situation in Aish 1992, p. 12. For the rise of the ready-made clothing industry in The Netherlands, including the Gerzon company, which was also a client of Studio Merkelbach, in connection with the rising prosperity, see Dercon 1980, particularly p. 6 and 18.↑

16. Dercon 1980, pp. 13 ff.↑

17. Het Leven, 8 (8 July 1913) 28, p. 889.↑

18. De Gracieuse appeared from 1862 to 1936. The magazine has been digitized and is accessible through the Geheugen van Nederland website: http://www.geheugenvannederland.nl/?/nl/collecties/modetijdschrift_de_gracieuse.↑

19. For instance, in the years 1913/1914 photos increasingly appeared on the cover of De Gracieuse, instead of fashion drawings. Beginning in 1914, they are accompanied by a credit to the photographer, from which it appears that these are foreign photographs, for example from Talbot and Henri Manuel in Paris.↑

20. Stephen Joseph writes on this, what he calls ‘direct use of an unadorned object in a spare studio setting’, see the paragraph ‘Product and image types and spread’ in Joseph 2012. ↑

21. De Gracieuse, 54 (1 March 1916) 5, 54 (15 March 1916) 6 and 54 (15 April 1916) 8, always p. 2.↑

22. Dekker 2007, pp. 4, 10-13, 16, 19, 22, 29, and others.↑

23. De Gracieuse, 53 (1 April 1915) 7 and 53 (15 April 1915) 8. After 1913, Hirsch is identified as the client in the business records of Studio Merkelbach.↑

24. Covers of De Gracieuse, 56 (2 January 1918) 1, 56 (16 January 1918) 2, 56 (1 February 1918) 3, 56 (16 February 1918) 4. One contributing circumstance was also that the First World War stopped the supply of fashion photos from Germany and France.↑

25. De Gracieuse, 56 (1 May 1918) 9, cover.↑

26. Regarding Eilers, see note 14. Studio Rembrandt is noted with a photo on the cover of De Gracieuse, 56 (15 May 1918) 10.↑

27. See for instance ‘Iets over de Zweedsche Huisvlijt’, 8 (1914) p. 358-362 and ‘Eenvoudige kleding’, De vrouw en haar huis, 9 (1 August 1914) 4, pp. 128-129.↑

28. Merkelbach was explicitly credited as photographer with this portrait. De vrouw en haar huis, 12 (October 1917) 6, p. 181.↑

29. Het Leven, 12 (6 Feb. 1917) 6, p. 193.↑

30. Panorama, 1 (2 July, 1913) 1, p. 11.↑

32. Anon., ‘”Kunstfotografie”. Merkelbach. Uit de goede, oude tijd’, Het Parool, 25 May 1963.↑

33. Hall-Duncan 1978, p. 9.↑

35. The name Barends (either as Miss or A.C. Barends) as a client appears a number of times in the Merkelbach business records, followed by ‘(Hirsch & Cie)’. Knoop indicates that this means that Barends was a member of the staff at Hirsch. E-mail by Knoop to the author, 18 June 2013.↑

36. Ewing argues that the first fashion photos are nothing more than photos that were made as studio portraits of actors. Ewing 1991, p. 10.↑

37. Faber emphasizes that, before 1920, the role of fashion photos was chiefly as replacements for the old fashion drawings. Faber 1983, p. 27.↑

38. Knoop 2011, p. 54.↑

39. Knoop 2011, p. 58.↑

40. Note on the negative sleeve of image 010164019152, now in the Amsterdam City Archives.↑

41. According to information in the business records of Studio Merkelbach, in 1921 the magazine Cinema en Theater commissioned photographs showing swimwear; see information with 010164005041, 010164005042, 010164019938, MER_192.↑

42. The carbon print was a laborious photographic procedure, which was primarily popular in art circles because of the unusual texture and permanence of the print.↑

43. Documents from Atelier Merkelbach suggest that the photo studio of Godfried de Groot was regarded as a competitor, whose name was not to be mentioned; documentation Merkelbach, Photo Collection, University Library, Leiden. Rooseboom also notes the competition between Atelier Merkelbach and the studio of Godfried de Groot. Rooseboom 1993, paragraph ‘Beschouwing’.↑

44.Hall-Duncan 1978, p. 9.↑

45. For a description of the nuances distinguishing a fashion photo from a portrait photo, see also Faber 1983, p. 27.↑

46. In 1918, a photo by Merkelbach appeared on the cover of five issues of De Gracieuse: issues 1, 2, 3, 4 and 9, of 2 and 16 January, 1and 16 February and 1 May, 1918, respectively.↑

47. Rijksmuseum Amsterdam, RP-F-F03932 verso. According to the Merkelbach administration files, the Sutterlui ladies lived at the address Van Eeghenstraat 57 in Amsterdam, which according to the Amsterdam immigrant status, housed the two Belgian women Marguerite van Becelaere (Ruddervoorde 1890) and Leonie Marie Louise Leopoldine Kempeneers (St. Truiden 1888). Veen 2013, p. 295, note 45.↑

48. Dekker 2007, p. 93.↑

References

Aish, Caroline, Katrina Rolley 1992, Fashion in photographs 1900-1920, London.

Bommel, Irma van 2012, ‘Modefotografie in Nederland’, Kostuum 2012. Jaaruitgave van de Nederlandse Vereniging voor Kostuum, Kant, Mode en Streekdracht, s.l..

Dekker, Annemarie den et al. 2007, Modepaleizen in Amsterdam 1880-1960, Bussum/Amsterdam.

Delft, Marieke van et al. (eds.) 2006, Magazine! 150 jaar Nederlandse publiekstijdschriften, Zwolle/The Hague.

Delhaye, Christine 2008, Door consumptie tot individu. Modebladen in Nederland, 1880-1914, Amsterdam.

Dercon, Chris and Henk Overduin 1980, Mode voor iedereen. Confectie 1880-1980, The Hague.

Faber, Monika 1983, Madame d’Ora, Wien-Paris, Portraits aus Kunst und Gesellschaft 1907-1957, Vienna/Munich.

Grijpma, Dieuwke 1999, Kleren voor de elite : Nederlandse couturiers en hun klanten 1882-2000, Amsterdam.

Hall-Duncan, Nancy et al. 1978, The History of Fashion Photography, New York.

Hegeman, Hedi and Ingeborg Th. Leijerzapf, ‘Atelier J. Merkelbach’ 1985, Geschiedenis van de Nederlandse fotografie: in monografieën en thema-artikelen, 2 (September 1985) 3, online version http://journal.depthoffield.eu/vol02/nr03/f05nl/en

Hohé, Madelief and Georgette Koning 2010, Voici Paris. Haute Couture, Zwolle.

Joseph, Steven F. 2012, ‘Early Advertising Photography in Belgium and the Netherlands: a Preliminary Overview’, Depth of Field, 3 (December 2012) 1, http://journal.depthoffield.eu/vol03/nr01/a04/en

Knoop, Femke 2011, Veranderd werd alléén… de tijd. Modehuis Hirsch & Cie, Amsterdam (1882-1940), Groningen (master thesis Rijksuniversiteit Groningen).

Leeuw, Kitty de 1991, Kleding in Nederland 1813-1920. Van een traditioneel bepaald kleedpatroon naar een begin van modern kleedgedrag, Hilversum.

Miellet, Roger 2000, Winkelen in weelde. Warenhuizen in West-Europa 1860-2000, Zutphen.

Nijenhuis, Hans ten and Ietse Meij 2002, Isaac Israëls. Mannequins en mode, Wijk en Aalburg.

Pouillard, Veronique 2000, Hirsch & Cie Bruxelles, 1869-1962, Brussels.

Rooseboom, Hans 1993, ‘Godfried de Groot’, Geschiedenis van de Nederlandse fotografie: in monografieën en thema-artikelen, 10 (October 1993) 22, online version http://journal.depthoffield.eu/vol10/nr22/f01nl/en

Teunissen, José et al. 2006, Mode in Nederland, Arnhem.

Veen, Anneke van (ed.) 2013, Fotostudio Merkelbach. Portretten 1913-1969, The Hague.

Weijl, Ivo, Notes prepared from the memories of Mr Kahn, 1966, unpublished typescript, Amsterdam City Archives.