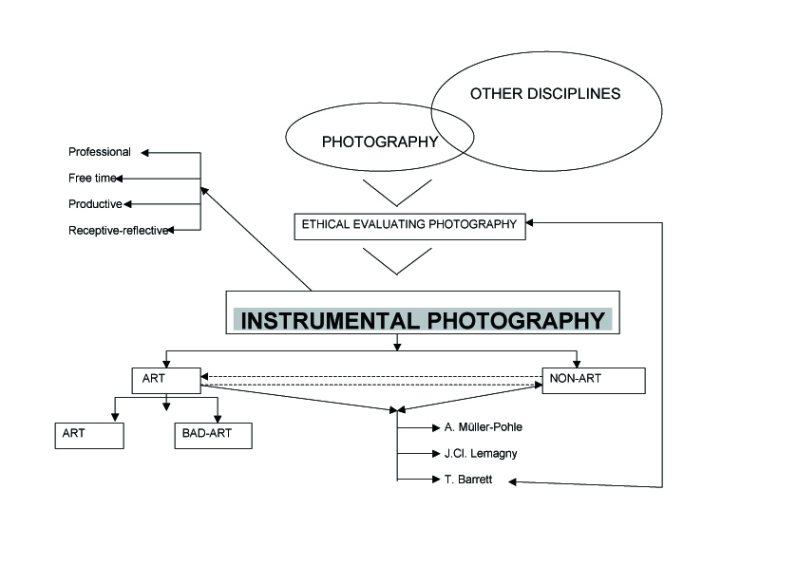

Instrumental Photography. The Use of the Medium Photography to Stimulate Empowerment

Abstract

There is no such thing as true photography. This paper aims at defining that kind of photography that is capable of stimulating emancipatory processes, empowerment and well-being. This sort of photography focuses not only on the actual act of photographing, but mainly on the process itself. Due to its specific characteristics, its reference to reality and its paradox, it is a powerful medium that allows alternative communication and storytelling. It is used as an instrument for education and socialization, i.e. for purposes other than its intrinsic one. I have therefore coined the term ‘instrumental photography’.

As a photographer, I apply instrumental photography to different target groups. All over the world, other photographers are doing the same. They all share the experience that images can indeed be used as tools for alternative communication. Words are regarded with greater distrust, while images are perceived as less threatening.

It was only in the last decennia of the previous century that sociologists, psychologists and philosophers provided instrumental photography with a theoretical basis that legitimizes the use of photography in an instrumental way. This new manner of thinking resulted in analysis models in which instrumental photography can be classified. As a conclusion, I designed a new model in which instrumental photography has been made the central theme in order to stimulate another way of thinking about photography.

Essay

Instrumental use of photography

Since 1997, I have been developing various photo projects for art education organizations such as De Veerman and Canon Cultuurcel, in which participants are encouraged to reflect upon themselves and society and to discuss these matters. My main point of interest here is the output of the process, rather than the images themselves. I notice that the participants gain more self-confidence, that they talk more easily about their family or dreams, and that they feel taken seriously. In my photo studio as well, I often experience that a good portrait gives self-confidence and that the process of being photographed – even before seeing the final result – produces a positive feeling.

One can distinguish between photography in which the end product is primary (such as an advertising photo, an art photo or a wedding photo) and photography in which the process is emphasized. In this paper, I am focusing on the latter. It is my aim to denominate and position this kind of photography in relation to other photographic practices. Can this kind of photography stimulate awareness and empowerment? To which category does it belong and how can it be classified? I call this kind of photography ‘instrumental photography’, analogous to the distinction between instrumental and intrinsic effects made in a number of investigations into the effect of cultural and art education.[1] I believe this is an important thing to consider. When a medium, in this case photography, pursues intrinsic goals, then we are talking about the medium itself. By this I am referring to the acquisition of knowledge and insight into the history of photography; reflections upon photography; the stimulation of an aesthetic perception in order to assess the quality of the context’s function; or the process of taking photographs oneself and learning to master the technical side of doing this. When you approach a medium instrumentally, things are different. One is then more concerned about personality or education (the self-image and emotional well-being); social education or socialization (social skills and interests, attitudes and value patterns); the influence on other fields of study, the cognitive skills (problem solving, intelligence factors, concentration). During photography workshops, participants are able to gain insight on a variety of topics, e.g. how to photograph or learning about famous photographers and various movements in the history of photography. Because the medium photography itself is the focus, these are intrinsic effects. When it comes to personal and social education, the medium is used as an awakening process. Several current cases can help in clarifying this.

Literacy through photography

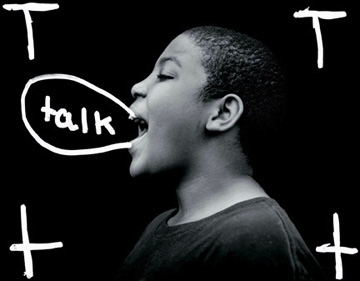

Wendy Ewald (b. 1951) is a photographer and professor at Duke University (Durham, North Carolina). In the late sixties, she started combining her documentary photography with workshops for children and young people, primarily in locations where they were living in primitive situations and facing exclusion and poverty. She gave her target group tasks related to their environment, such as taking a self-portrait or a photograph of their family or village. By allowing these children to photograph their own situation, by having them explain why they chose to photograph something (or why they chose not to), they were given a certain authority. By operating the camera themselves, they were being taken seriously, which in turn stimulated their self-esteem. Afterwards, these photographs were exhibited with the children presented as the author, i.e. someone who has something to tell and to show. In 1990, Ewald developed the method Literacy Through Photography, designed to use photography as a means of improving literacy. (fig. 1) Using captions, legends and notes, children learn about reading and writing, and even visual literacy. As they become increasingly familiar with the camera, they are encouraged to imagine and talk about subjects that are more abstract, such as dreams and feelings. This can act as a stimulus for their self-confidence: ‘For most children, especially those who seem to be without a secure place in their classrooms, learning photography can be helpful in building self-esteem and self-confidence. Making photographs and writing about them offers a safe haven where kids can describe the realities of their lives, deal with some of their pressing problems, and articulate their hopes and fears.’[2]

Transformation from pain to power

In addition to Wendy Ewald, we also have – on the opposite side of the world – the Indian photographer Achinto Bhadra. In 2007, Bhadra (b. 1959) photographed 126 girls for the project Another me, transformation from pain to power. Together with Harleen Walia, he worked for several months at the Sneha Girls Shelter, a centre for abused and abandoned girls. Walia, a coordinator with Sanlaap, the NGO that had founded the shelter, recorded the testimonies of 126 girls and women between the ages of eight and twenty-five. She as well guided them through the process of telling their own personal story. As each of the girls spoke about their past, they were also asked to process it by thinking about a fictitious character, an ‘alter ego’, that they would like to be or become. In doing so, they were able to develop a fictional personage to embody exactly what they wished to express or address. Their pain, anger, hope and expectations were ventilated through this ‘other-me’. The girls dealt with their trauma by talking about it with their peers and being photographed as this other version of themselves.[3] ‘For a moment, each felt the power within herself. And today, that brief transformation remains an inner source of confidence and strength.’ The result is a powerful series of beautiful coloured photographs, in which the girls convert their pain and anger into hope and strength. Once again, we observe that it is the whole process, rather than the actual photographs, which achieves this transformation. In other words, the photographic medium has been used as a means of improving the subjects’ self-empowerment. When asked the question of whether the photographs contributed effectively to these girls’ empowerment, the photographer responded: ‘Photography is just a medium. It was the process that gave them a new life.’[4]

Reconstructing history

Rich Wiles (b. 1974) as well teaches photography to young people. In 2005, this British photographer travelled for the first time to Palestine in order to cover the life in the refugee camps. But Palestine is not his country. It was not his aim to produce (photographic) stories about the Palestinians, but rather to help them tell their own story – and especially the young people. Wiles guided them in the visualization of their dreams and nightmares, their hopes for a world of freedom, equality and justice. They learned about the rights of the child and were asked to make photographs representing this theme. The pictures, together with the personal testimonies, were exhibited in the camp. Through the sponsorship of the British Consulate, the Pontifical Mission, and the Belgian Development Aid, they were published and disseminated around the world. Wiles: ‘Together we believed photography could play an important role alongside other forms of creative expression used in the center to address issues of marginalization, empowerment and self-expression. Photography offers Palestine’s children a vehicle for expressing their thoughts and their situation to the outside world without the necessity of the artists themselves needing to travel.’[5]

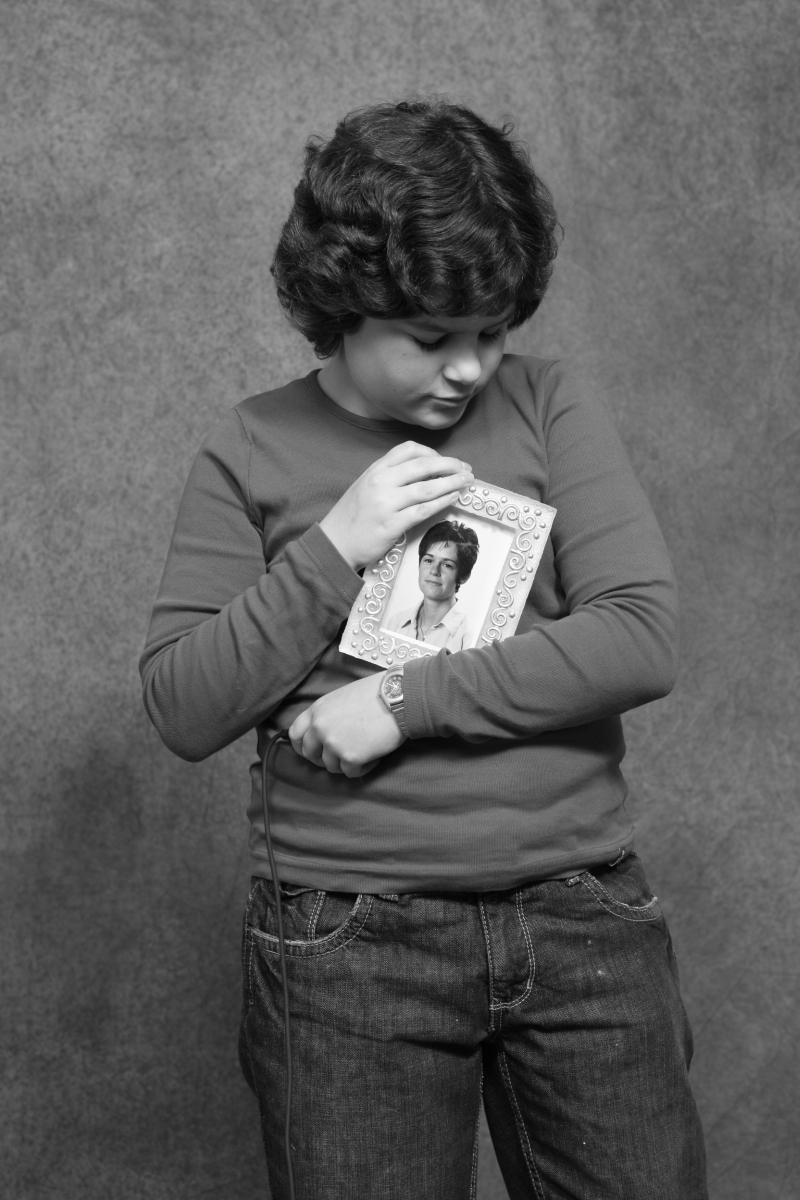

In the Dreams of Home project (2007), Palestinian children were asked to interview their grandparents about the war in 1948, at which time they were expelled from their homes and surroundings.[6] (fig. 2) Under the guidance of international volunteers, they went into the areas where their grandparents were born and they took photographs. By doing this young, Palestinian refugees were given an opportunity to reconstruct their past and as well as a personal and collective memory.

|

Fig. 2.Rich Wiles, Muftah al-Awda (Key to return), Palestine 2007. ‘I dream about being granted the Right of Return to our original villages which were occupied by Israel in 1948.’ Rich Wiles. |

Wendy Ewald, Achinto Bhadra and Rich Wiles are all photographers who, besides taking photographs themselves, use the medium to enhance emancipatory processes and to empower participants in their photo projects. In many cases, the personal history of the participants, e.g. Rich Wiles with the children at the Lajee refugee camp, is reconstructed or problematized.

Identity and empowerment

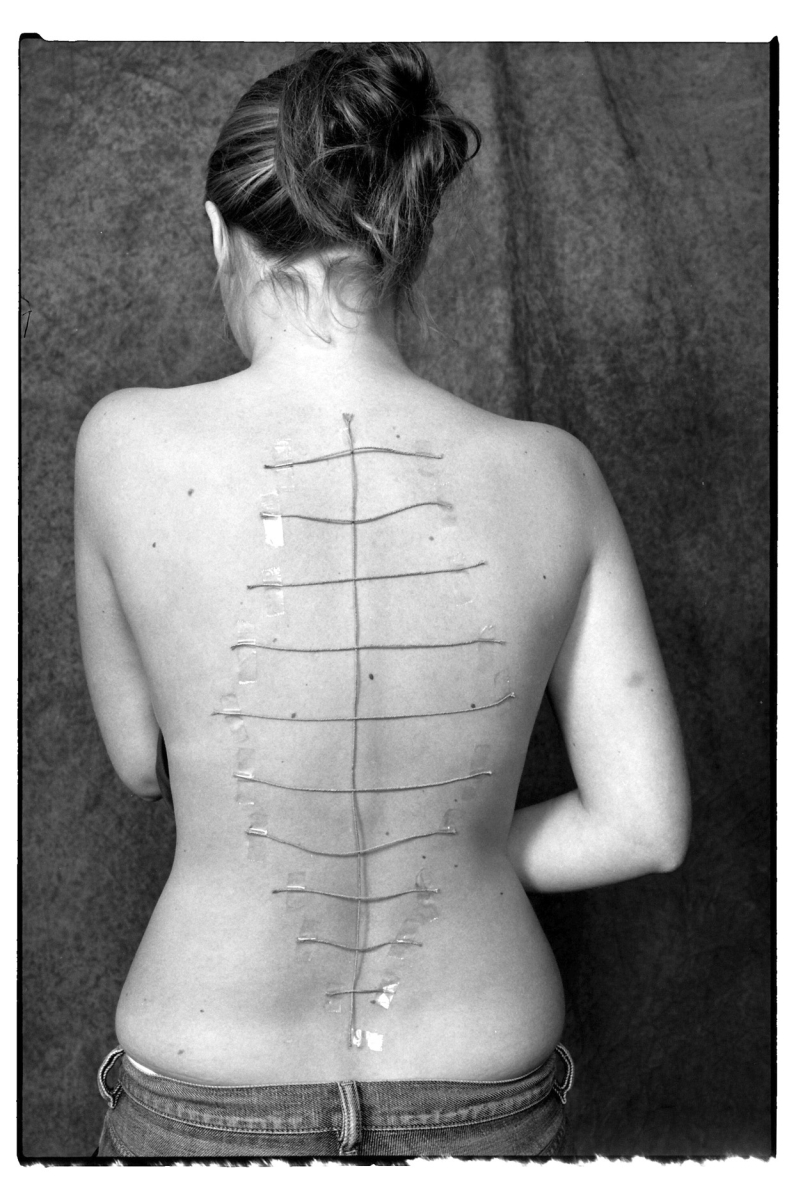

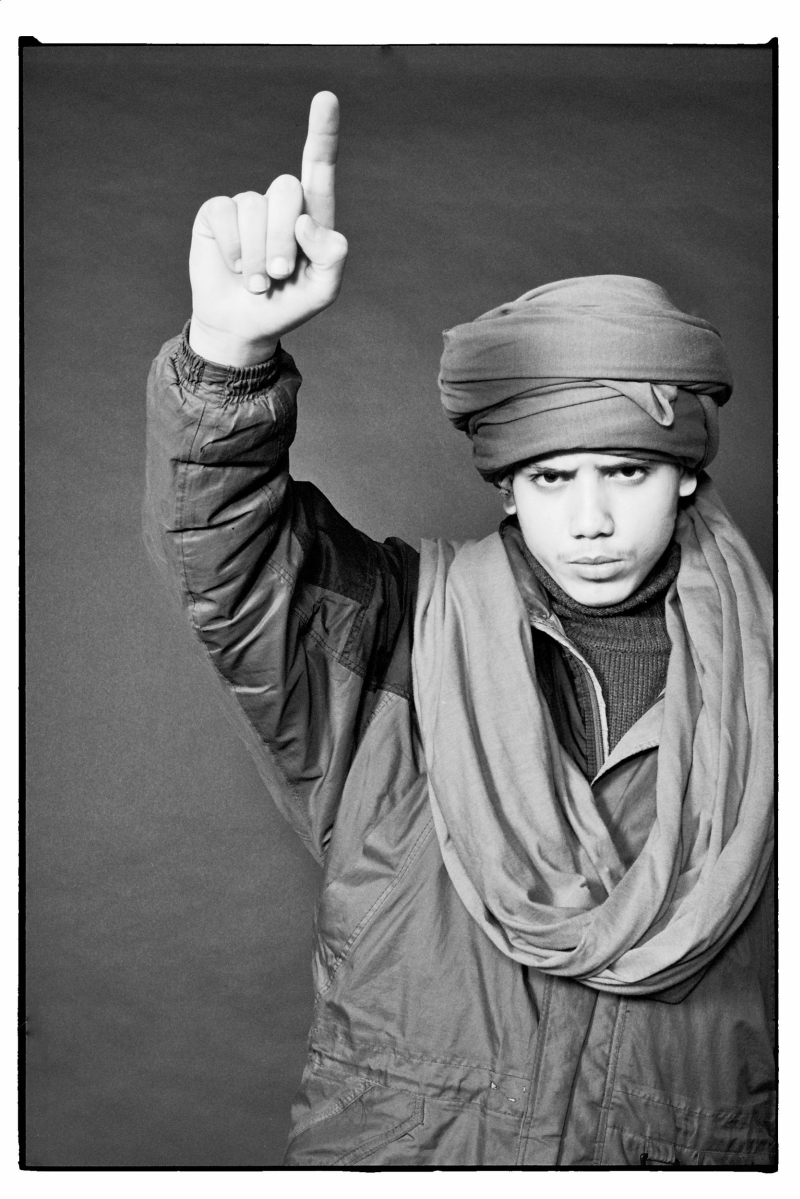

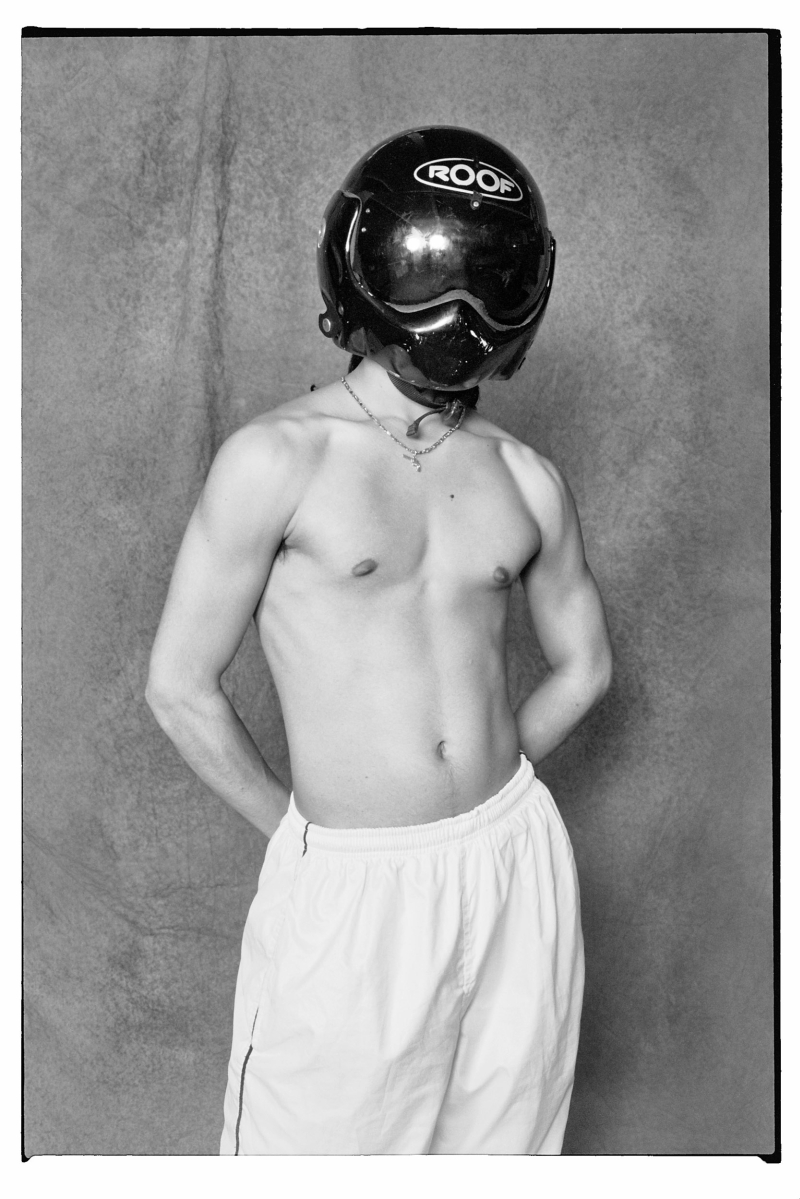

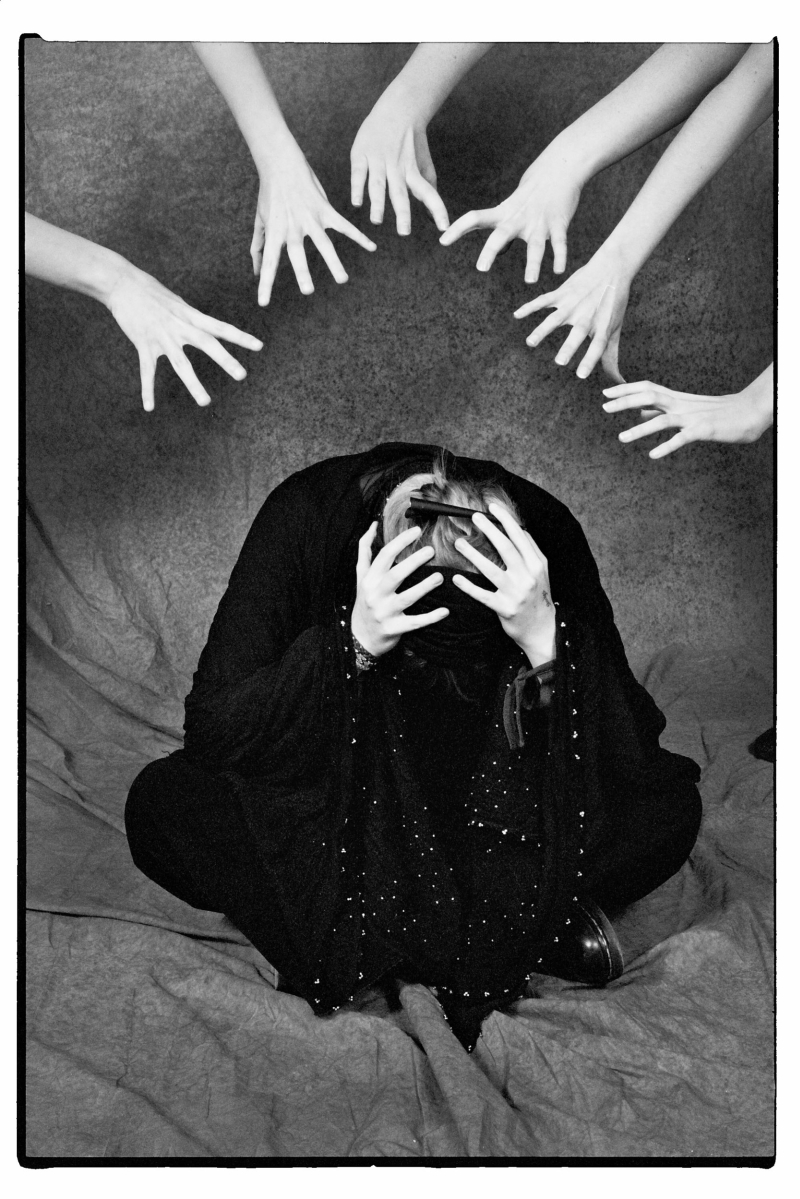

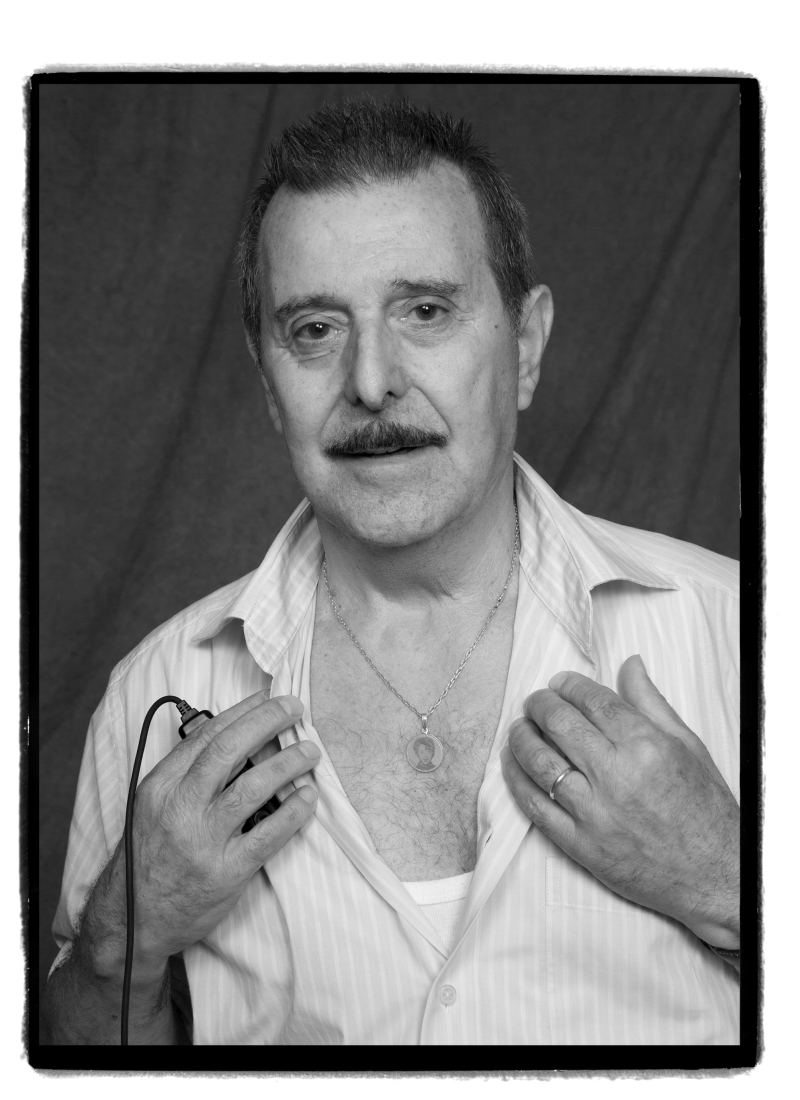

I myself have organized photo workshops on ‘identity and empowerment’ for different target groups such as disabled people, cancer patients (figs. 3, 4 and 5), immigrant youths (figs. 6 and 7), women of varying ages (fig. 8), adolescents (fig. 9) and parents of children that were killed in traffic accidents (fig. 10). Focusing on a specific target group allows one to delve more deeply into it. The participants undergo the same experience and feel more at ease and better understood by the group. They are companions, as it were. In every workshop, I could see that this had a positive effect on the participants, instilling confidence and bringing satisfaction.

|

Fig. 4. Hilde Braet, Scars, from Portrait=Self-portrait!?, Ado weekend Children’s Cancer Fund, Brugge 2003. Hilde Braet. |

|

Fig. 6. Hilde Braet, Who am I?, from Kids Pur Sang, De Veerman Project, Antwerp 2003. Hilde Braet. |

|

Fig. 7. Hilde Braet, Who am I?, from Kunst en Techniek (Art and Technics), Canon Culture Unit – Ministry of Education, Ghent Institute for Technical Education, Ghent 2007. Hilde Braet. |

|

Fig. 9. Hilde Braet, Bullying, from Kunst als protest [Art as Protest], Onze-Lieve-Vrouwecollege, Halle 2005. Hilde Braet. |

|

Fig. 10. Hilde Braet, Paul with photo of his dead child around his neck, from Jezelf voor en door de lens [Yourself in front of and through the lens], Ghent 2011. Hilde Braet. |

In my 2010 master’s thesis, I investigated two projects in detail: one project that concerned middle-aged women and a second involving adolescents suffering from cancer.[7] Within the framework of this paper, the findings about how instrumental photography works are most significant. We concluded that working with photographs is a powerful means of communicating in a different way. Although the initial impetus is playful, challenging, and at times difficult, it is likewise experienced as being less menacing than when compared to conventional approaches to conversation. Again, working with images stimulates conversation. The various ways in which a photograph can be interpreted gives one a freedom that – especially in the case of the young patients with cancer – must certainly seem light to bear when compared to jargon used by therapists, educators, doctors or parents. Both the youths and the women dared to expose their vulnerability, experiencing this as a victory and a sense of being understood. As the psychologist the counselled the photo workshop observed: ‘This process of surpassing yourself, showing something of yourself, telling something to another in a way that does not involve words […] is so powerful.’[8]

Photography and therapy

There are pictures everywhere and everyone has a camera to take them. You press the button and the image appears. This is the reason why working with pictures is easily accessible and everyone can do it. For many people, it is a tool to express themselves in a way that is less complicated than words. Pictures refer directly to a reality that can be given significance. This significance is not contained in the image itself, but instead constructed through denotation and connotation, which lead to a subjective interpretation. The medium’s singularity is also applied in therapeutic photography. Psychologist and art therapist Judy Weiser, who is the founder and director of the PhotoTherapy Centre in Vancouver and considered to be an authority on the emotional meaning of photographs, defines ‘Therapeutic Photography’ as photographs of individuals taken by and for themselves in non-therapeutic settings for the purpose of their own personal growth and insight.[9] Therapeutic Photography is to be distinguished from ‘PhotoTherapy’, which she defines as photography used by therapists, i.e. trained mental health professionals, as part of their formal psychotherapeutic process.

From 1983 to 1992, Rosy Martin (b. 1946) and Jo Spence (1934-1992) analysed the concept of ‘identity’ by taking self-portraits and photographing the course of Spence’s disease process. In 1982, Spence was diagnosed with breast cancer. From that time forward, she took self-portraits, often in cooperation with Martin, portraying her battle with her illness. She tried to make explicit the social construction of identities with the drama of daily life. Photographic images form our sense and our feeling of reality. The tension between the various truths or contradictions implied by a picture is productive in the therapeutic process. It becomes clear that ‘the truth’ is a construction and that ‘identity’ is fragmented by these various truths. The ‘perfect self’ as a given and unalterable thing is non-existent. The ‘self’ is a process in itself.

Martin and Spence made self-portraits and browsed through their family albums. Most family albums show the same events: they belong to different individuals but still resemble each other. They do not tell us about the life of the individual himself, but reflect what was considered the social norms and values and important moments in a given period. The traditional family album does not tell us the whole story. It is also the construction of a desired reality as well as a fragmentary reproduction of what is and should be, steered by the habits of the society in which one lives. The pictures from the family album are often commonplace, but because they are emotionally charged, we cannot do without them.[10] Martin and Spence drew attention to events that were not worth including in the family album, such as pictures of disease, death and daily tasks. They created an alternative family album, showed censured aspects of life, and shaped another sense of reality that contrasted with the predominant visual culture. Seeing less flattering pictures and accepting them as a part of life can have a healing effect. In this manner, they also reconstructed their personal history and criticized vexing social issues, such as the objectification of the patient and the stereotyping of lesbian women.[11] Becoming the subject of your own life – and not the object – gives empowerment to those who are constructed and stereotyped based on their sexuality, disability, age, gender, race, and class.

Positioning of instrumental photography

Instrumental photography falls outside the canon of the current (photographic) history. It has little to do with art. How it technically came about is not what is most important. Instrumental photography is rather focusing on the use and reception of images. It flourishes in different contexts. The ‘why’ of photographing is something that is equally as important as the technical ins and outs. The function of pictures is not neglected: as such, we think about the relation of the picture to both the client and the maker, the observer, and the time and place where it is produced and shown. In order to receive its proper recognition and appreciation, it is important to find a suitable category or to find an adjusted system of classification. A system of classification implies a new way of looking at reality.

Development of instrumental photography

Has there always been attention for photography of this nature? In its rather brief existence, photography has undergone a great deal of alteration. In the beginning, artists and academic researchers focused mainly on the question whether photography should be considered an art or a science. Particularly the end product and the technological process were seen as most important. It was not until the close of the previous century that attention was paid to the awakening process that working with images can induce. Pierre Bourdieu (1930-2002) studied photography starting from a totally different discipline: sociology.[12] He referred to the importance of family pictures and family albums as a ‘unifying factor’ and an ‘integration rite’. ‘Normal’ pictures are important as a social support and to reconstruct an identity, whether at the individual or national level. These normal pictures, which have no pretensions of being art, are called ‘vernacular photography’. They were also important for the philosopher Roland Barthes (1915-1980) as an object of memory and as a testimony of what no longer is but what once was.[13] The psychological influence of (photographic) images was also taken into account by the psychologist Rudolf Arnheim (1904-2007).[14] Through the influence of the philosopher Vilém Flusser (1920-1991) as well, (photographic) images were seen increasingly as a means of communication.[15] Semiotics, discourse theory and reception investigation became important fields of study. More emphasis was placed on active processes of signification through photographic images. Attention was also paid to the veracity and authenticity of the medium. Photography indeed refers directly to reality. In the last few decades of the twentieth century, the question of whether photography is art was no longer the most relevant. Photography is simply different from traditional art disciplines: such comparisons detract from its uniqueness. As a consequence of this shift in mentality, photo analysis models were developed by which instrumental photography could be classified.

Analysis models of the photographic image

These new approaches to photography became the impetus for new typologies, which, because they were indications rather than strict classifications, were referred to as photo analysis models.

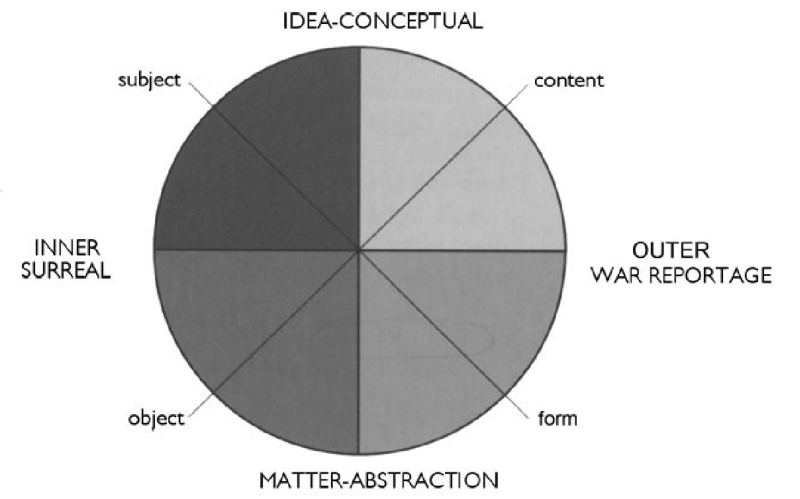

In 1981, Jean-Claude Lemagny (b. 1931), curator of the photographic collection of France’s national library Bibliothèque nationale de Paris from 1968 to 1996, developed a classification system which he published in La Photographie: Tendances Récentes. [16] His model, which is called ‘Lemagny’s clock’, can be applied to various aspects of instrumental photography (fig. 11). It consists of four segments, with each divided into specific areas of interest, enabling one to classify and label photographic content. He distinguishes between distinct categories arranged in clockwise order:

-

reportage: comprising the narrative of both classic as well as more extreme forms of reportage, e.g. war reportage;

-

an expressionistic approach;

-

form and matter, abstraction;

-

the inner and the surreal;

-

conceptual photography: photography as a theory about itself and the exploration of its own limitations.

Lemagny states that this classification is not intended as a dogmatic approach to photography, but rather a starting point for discussion. A single photograph can fit into several categories. Just as a clock has two hands, the same photograph can refer to multiple categories. [17]

What place does instrumental photography have in this model? It is not possible to select one segment, because all depends upon the accent and the intention of the photo(grapher).

When the narrative and the expressive are important, this type of photography can be placed between the hours of 3 and 6 on the right-hand side of the clock. As the expressive form becomes more predominant, this type of photography moves closer to 6 o’clock. If instrumental photography deals with the inner world, around the 9 o’clock mark is a more suitable location. Lemagny frequently focuses on photography that explores the possibilities and limitations of photography. However, he fails to consider photography that is used to criticize systems or persons and that enables changes in certain situations.

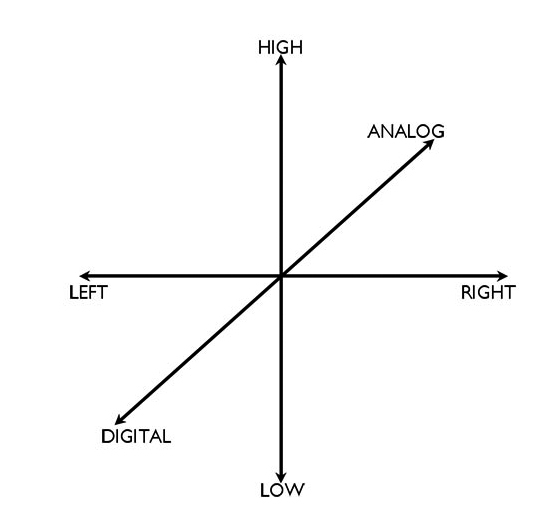

In ‘The Photographic Dimension’ (1993), Andreas Müller-Pohle (b. 1951) addresses instrumental photography in his model. He distinguishes between three current trends in contemporary photography: an aesthetic trend, a technological trend and a political trend. The aesthetic trend considers the struggle between ‘high’ and ‘low’ images, between ‘art’ and ‘non-art’, between ‘elitist’ and ‘folk’, between the Art world (with a capital ‘A’) and the socio-artistic world. The technological trend covers the contrast between analogue and digital images. The political trend discusses the opposition between right- and left-wing images. It is possible to visualize this model using a three-dimensional coordinate system. The aesthetic tendency (low to high) is shown on the vertical axis; the political tendency (left to right), on the horizontal axis; and the technological tendency (digital to analogue) on the diagonal axis (fig. 12).

Instrumental photography aims at strengthening awareness and change processes. But which changes? What is the standard? What is good, what is evil? In the Müller-Pohle model, instrumental photography is clearly situated on the left of the political axis. The critical questioning of existing conditions (political, social, personal) is a progressive act, designed to break the ‘status quo’ of entrenched opinions. It involves constant reflection on so-called ‘natural’ situations. This is a left-wing attitude. The aesthetic quality of instrumental photography is not the most important criterion. It can produce both ‘high’ and ‘low’ images and therefore balances on both sides of the vertical axis of The Photographic Dimension. Whether instrumental photography is now becoming analogue or digital is irrelevant, as it is the genesis of the photograph that prevails, just as the effects on the individual and their environment.

In Müller-Pohle’s approach, there is also a new element: the ‘staging’ function. Every photograph, even the simplest, involves an intervention: the way the light is captured, the way its backdrop is created, the specific way it is produced. He distinguishes between six ways of staging: the staging of the object (the choice of what is photographed and how), the staging of the subject (the photographer photographing himself), the staging of the apparatus (the camera is used in an unusual manner), the staging of light (which light helps create the image and in what way does it affect it), the staging of the image itself (the further development of existing image material) and the staging of the context (the meaning is influenced by the place where the photographs are presented).

When his model is applied to the examples discussed, in particular to the photos created under the guidance of Wendy Ewald, it can be concluded that these photos are stagings of the object, the subject and the context: staging of the object, because her target group thought about the way they wanted to portray themselves and their environment; staging of the subject, because the photos are the result of her mediation-manipulation; staging of the image, because she scratches texts on the negatives or combines them with autobiographical texts written by the children; staging of the context, because the photos are shown in galleries as well as in the rural communities of her participants. Consequently, one can apply the Müller-Pohle model to position instrumental photography, though the niche in which it belongs is not yet defined.

A place in the world of photography

Terry Barrett (b. 1945), author of Criticizing Photographs. An Introduction to Understanding Photographs (1990), organizes photos around the four major activities of criticism: description, interpretation, evaluation and theorization. This in turn prompts four basic questions: what is it, what is it about, how good is it, and is it art? In the latest edition of his book, Barrett has added a fifth question: is it right?[18] Is it fair, just, good, legitimate or right? Can photographs have a moral component? These are important questions, which lead us to one of his six categories, namely ‘ethically evaluative photography’. The other categories are: descriptive photographs, explanatory photographs, interpretive photographs, aesthetically evaluative photographs and theoretical photographs. Just as with Lemagny, Barrett indicates that photographs can belong to several categories at the same time. He also states that his model is aimed at feeding the debate, without being in any way dogmatic. He not only attaches importance to subject and form, but also to the function of photographs. This places the photograph in the context of its relation to the client, the maker, and the viewer, as well as the time and place where it was produced and shown.[19]

Barrett provides a solid theoretical basis for seeking the potential ethical aspects of photography – and instrumental photography – that are inextricably linked to ethics. Whoever is committed to change is also committed to ethics. Indeed, according to which criteria should these processes be initiated? How can we find out what is good and what is not? What can be shown and what cannot? What are the standards and values with which we can act? These are life-defining questions. This is where photography that aims to induce emancipatory processes, education and socialization belongs. So far, Barrett is the only critic to have developed a photo analysis model in which ethics holds a significant place. Since instrumental photography prompts ethical reflections, it belongs to the category of ‘ethically evaluative photography’.

A new angle

Instrumental photography falls outside the canon of conventional (photo) history. The enclosed model I have designed offers a new perspective, departing from the notion of instrumental photography as a part of ‘ethically evaluative photography’, a category from Barrett’s photo analysis model (fig. 13). Instrumental photography can be ‘Art’, but it does not have to be. If instrumental photography belongs to the Art category, it can either be ‘Art’ or ‘Non-Art’, depending on the prevailing quality criteria as determined by critics. It is possible for instrumental photography as Non-Art to turn into Art, as a result of changing contextual influences. By the same reasoning, Art can indeed become Non-Art. Instrumental photography as Art and Non-Art can be further analyzed in the models provided by Müller-Pohle, Lemagny and Barrett. Instrumental photography may also be approached from other angles. It can be practiced by anyone who works with photography on a professional level (a photographer, lecturer in visual culture, etc.) or an autodidact who uses the medium in a leisure environment. It may be a case where photographs are actually taken (productive), but the images can also be used to initiate discussions (receptive-reflective). There may be some overlapping between these areas. For example, a photographer may lead work seminars as a volunteer, where both the meaning of photographs is discussed and photographs are taken.

Conclusion

Until the end of the twentieth century, photography used as a means of promoting empowerment, emancipatory processes and well-being was rarely mentioned. Throughout the relatively short existence of this medium, more emphasis has been placed on the technology and on whether or not it is to be considered as art. As we enter the twenty-first century, photography has increasingly opened up to other disciplines and is no longer studied exclusively in the art sciences as part of (art) history. The importance of the photographic image is situated in a broad social context. It is studied from a sociological, philosophical, (cultural) historical, agogic, ethical, technological, psychological, feminist, multicultural, neo-colonial, and homosexual perspective. It is also approached from the contextual use of the medium, thereby contributing to the definition of its meaning. As the uniqueness and versatility of the medium are gradually more valorised, it goes without saying that its approach should be interdisciplinary. As a result, questions relating to art or science are no longer essential. Instrumental photography is an expression of this. It can fit into various segments of contemporary photo analysis models and is always concerned with ethics. It can also be approached as the core of contemporary photography, possessing a subjective and/or socially engaged message, as well as a large- or small-scale communication medium. In this way, instrumental photography takes its place alongside other photographic practices.

CV

Hilde Braet is Qualified European Photographer and Master in Cultural Sciences (Visual Culture). In 2011 she was awarded the Max van der Kamp Scriptieprijs for her master thesis Aspects of Ethical Photography. Research into the Possibilities of the Medium Photography to Contribute to Emancipatory Processes, Empowerment and Well-Being. She is author of De kracht van een foto (2012); Ontbloot, Erotische Vernaculaire Fotografie (2012); and of Zelf(in)Beeld (2010). A selection of her articles are ‘De kracht van fotografie’, Cultuur+Educatie, 11 (2011) 32, pp. 10-27; and ‘Zelf(in)Beeld’, Magazine de Geus, 42 (2010) 9, pp. 32-35. She was curator of the exhibitions Met het oog op Boon (Hof van Ryhove, Ghent 2012); Ontbloot, Erotische Vernaculaire Fotografie (Lakenmetershuis, Ghent 2012); and Zelf(in)Beeld (Geuzenhuis, Ghent 2010). ↑

Notes

1. John Harland (Harland 2008) as well as Folkert Haanstra (cited by Stuivenberg and Van der Goot 2006) outline the instrumental and intrinsic effects for cultural and art education. Harland is freelance researcher and director at LC Research Associates. He was previously the head of the Northern Office in York of the National Foundation for Educational Research. Haanstra is a professor of art education at the Amsterdam School of the Arts and holds the special chair for Cultural Education and Cultural Participation at Utrecht University.↑

2. Ewald and Lightfoot 2001, p. 135.↑

3. For the pictures see: http://www.anotherme.org/about.htm ↑

4. Bhadra cited by The Guide Team 2010.↑

5. Wiles 2008, p. 2.↑

6. Wiles 2007.↑

7. Braet 2010.↑

8. Braet 2011, p. 25. ↑

9. See Weiser’s website: http://www.phototherapy-centre.com ↑

10. Batchen 2008, p. 27.↑

11. Martin and Spence 2003, p. 405.↑

12. Bourdieu 2007.↑

13. Barthes 1980.↑

14. Arnheim 1974.↑

15. Flusser 2007.↑

16. La Photographie: Tendances Récentes, Paris 1981; actualised: La Photographie: Tendances des Années 1950-1980, Paris 2002. In this work Lemagny proposes an ordering of the principal trends in photography.↑

17. Swinnen 1992, pp. 260-280.↑

18. Barrett 2006, p. IX. It is interesting to compare the first edition of 1990 with that of 2006 (which I used as a reference). Not only is the latest edition enriched with numerous (colour) reproductions, but its content is also more extensive and deals much more with ethics.↑

19. Barrett 2006, p. 208.↑

References

ARNHEIM, Rudolf, Art and Visual Perception: A Psychology of the Creative Eye, Berkeley/ Los Angeles/London 1974.

ARNHEIM, Rudolf, ‘On the Nature of Photography’, Critical Inquiry, 1 (September 1974) 1, pp. 149-161.

BARRETT, Terry, Criticizing Photographs: An Introduction to Understanding Images, Mountain View 1990.

BARRETT, Terry, Criticizing Photographs: An Introduction to Understanding Images, New York 2006.

BARTHES, Roland, La Chambre Claire: Note sur la Photographie, Paris 1980.

BATCHEN, Geoffrey, Each Wild Idea: Writing, Photography, History, Cambridge/ London 2002 [2001].

BATCHEN, Geoffrey, ‘Les snapshots: l’histoire de l’art et le tournant ethnographique’, Etudes Photographiques, (October 2008) 22, pp. 5-38.

BHADRA, Achinto, ‘Achinto Bhadra’, in: Christian Lacroix (ed.), Christian Lacroix et Ses Invités, Arles 2008, pp. 50-53.

BOURDIEU, Pierre, ‘Culte de l’unité et différences cultivées’, in: Pierre Bourdieu, Un Art Moyen. Essai sur les Usages Sociaux de la Photographie, Paris 2007 [1965], pp. 31-106.

BRAET, Hilde, Aspecten van ethische fotografie. Onderzoek naar de mogelijkheden van het medium fotografie om een bijdrage te leveren aan emancipatorische processen, weerbaarheid en welbevinden, unpublished master thesis Cultural Studies, Vrije Universiteit Brussel, Brussels 2010.

BRAET, Hilde, De kracht van een foto, Antwerp/Apeldoorn 2012.

BRAET, Hilde, ‘De kracht van een foto’, Cultuur+Educatie, 11 (2011) 32, pp. 10-27.

DUBOIS, Philippe, L’Acte Photographique et Autres Essais, Brussels 1990 [1983].

EWALD, Wendy and Alexandra Lightfoot, I Wanna Take Me a Picture: Teaching Photography and Writing to Children, Boston 2001.

EWALD, Wendy, The Best Part of Me: Children Talk About Their Bodies in Pictures and Words, New York/Boston 2002.

FLUSSER, Vilém, Een filosofie van de fotografie, Utrecht 2007 [1983].

HARLAND, John, ‘Voorstellen voor een evenwichtige kunsteducatiemodel’, in: M. van Hoorn (ed.), Gewenste en bereikte leereffecten van kunsteducatie, Utrecht 2008, pp. 12-54.

McCAULEY, Anne, ‘Arago, l’invention de la photographie et le politique’, Etudes Photographiques, (May 1997) 2. http://etudesphotographiques.revues.org/index125.html, (Accessed on 21 April 2010)

MARTIN, Rosy and Jo Spence, ‘Photo-therapy, Psychic Realism as a Healing Art?’, in: Liz Wells (ed.), The Photography Reader, London/New York 2003 [1988].

MÜLLER-POHLE, Andreas, ‘The Photographic Dimension’, European Photography, (1993) 53. http://www.muellerpohle.net/texts/essays/ampthephotographicdimension.html (Accessed on 2 May 2010)

STUIVENBERG, Richard and Anna van der Goot, Interview with Folkert Haanstra: ‘Kunstdisciplines zijn leerbare symbooltalen’, 20 December 2006.http://www.dirkmonsma.nl/dirkmonsma/cms/cms_module/index.php?obj_id=450 (Accessed on 1 May 2010)

SWINNEN, Johan, De paradox van de fotografie: een kritische geschiedenis, Antwerp 1992.

SWINNEN, Johan, De lichte kamer. De onverborgen fotografie, Antwerp/Apeldoorn 2005.

THE GUIDE TEAM, ‘Project Phoenix’, MID-DAY, 8 March 2010. http://www.mid-day.com/articles/project-phoenix/74348 Accessed on 19 November 2014)

WEISER, Judy, PhotoTherapy Techniques: Exploring the Secrets of Personal Snapshots and Family Albums, Vancouver 1999 [1993].

WILES, Rich, Dreams of Home, Lajee Center 2007.

WILES, Rich, Our Eyes: Photography by the Children and New Generation of Lajee Center, Lajee Center 2008.

WILES, Rich, Behind the Wall: Life, Love, and Struggle in Palestine, Washington 2010.