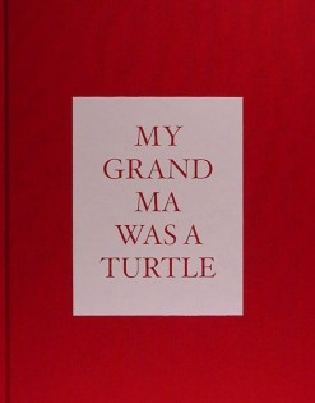

Cuny Janssen: My Grandma was a Turtle, in Female Power, Museum voor Modernde Kunst Arnhem, 2013

Opening in March 2013, the exhibition named Female Power takes place at the Museum of Modern Art in Arnhem (Museum voor Moderne Kunst Arnhem – MMKA). The works of twenty-two female artists, of different backgrounds, nationalities, races, interests and purposes, are framed within the themes of matriarchy, utopia and spirituality. The exhibition displays all kinds of media: photography, sculpture, performances, video and painting. What unites all contributions is an interrogation of stereotypes, norms, and established orders, and the production of new knowledge and new narratives by those that do not entirely fit the normative Western, white, middle-class, masculine artistic practice.

In this review, I will focus on the work of Cuny Janssen, a Dutch photographer who positions herself at the crossroads of sociology, history and anthropology. Indeed, her artwork is related to the main aspects of the Female Power exhibition: removing stereotypes and challenging patriarchy and its way of knowledge production. In the MMKA, Janssen presents her project, My Grandma was a Turtle (2008). For this project Janssen went to Oklahoma in order to portray children from a clan of the Delaware Indians named Turtles, descendants of Native American clans that have been raised as other American children. However, the children have also been educated about their own particular history and culture. Portraying these children, Janssen traced the similarities between American Indians and their peers, the descendants of American colonists. The project stems from Janssen’s curiosity to “see just how much of the children’s Indian ancestry would be visible” [1]. Yet rather than visiting Indian reserves, as many photographers did before her, she steered clear of representations of Indians as “evil blood-thirsty primitives, unworthy of owning land” [Janssen, 2010], with the aim of counteracting the old Indian stereotypes.

Janssen’s project expresses a need to document the people and the world. Drawing upon Edward Steichen’s exhibition Family of Man (1955), Cuny is fascinated by the fact that all people are somehow different and yet similar at the same time. Indeed, when Steichen curated this exhibition, setting up the work of 203 photographers at the Museum of Modern Art in New York, his intention was to see, through photography, the universality of human experience. Moreover, Family of Man attempted to draw up a “mankind’s portrait”, where disparity and likeness in human experience come to the fore through the documentary aspect of photography [Rouillé, 2005]. Janssen attempts to record this paradox in her photographic portraits, as she states in her talk:

“I am convinced that all people are essentially the same, whether rich or poor, intelligent or simple. The amazing paradox, however, is that each person is also unique. Every person is formed by different life experiences and each creates his or her own mix of human generalities. Ultimately, it is phenomenal to discover the individual in each person – valuable, dignified and authentic.” [2]

What do you see when you look at me?

In her work, Janssen searches for uniformity. The portraits are mostly generally framed closely, revealing the details of the children’s features. The images are clear and clean; nothing distracts the viewer from the facial expression. Ethnic markers such as dark and long hair, dark eyes, and brown skin, alternate with blond hair and blue eyes. Familiar stereotypes fail us here. The portraits are regularly juxtaposed with pictures of the surroundings, showing primarily nature: fields, rocks, lush grasses, rivers, or lakes.

Janssen’s approach to her photographic practice is characterised by a need to look at the face of a younger generation as a sign of the future. Her work reminds us that past, present and future cannot be grasped in one photographic shot; nor can the subjects’ identity be represented. In her Cyborg Manifesto, Donna Haraway observes that the body/face is the bearer of meanings sustained through cultural, historic and scientific discourses. Consequently, by searching for physical signs of the Indians’ past in children’s faces and not finding them, Janssen deconstructs the importance that we bestow on ethnic origin, and consequently, physical discrimination. Native Americans – commonly associated with adjectives such as “wild”, “primitive”, “barbarian”– have been viewed in mainstream opinion as equivalent to alcohol addiction and unemployment problems. By erasing common cultural beliefs and clichés placed upon these “Others”, she allows space for the process of re-interpretation on the part of the spectator. Janssen relates her artwork to the German notion of “hineininterpretierung”, which means interpreting, giving or putting a meaning into something after-the-event, and producing an unintended meaning, which most of the time suits one’s own thinking. The photographer retains the information regarding each child, withholding names, tribes, and locations. Only in the book My Grandma Was A Turtle is this information provided. As such, Janssen’s work can be linked to what Roland Barthes looked for in photographs, notably in his Camera Lucida: to make visible what it is not. [Sentilles, 2010]: p. 508]

At the same time, each image constitutes the presence of an absence, making us aware that images of contemporary Indians cannot be read without remembering the old clichés. The way in which we depict others, the way we expect them to be, and the way we look at each other can never be objective: photography always entails taking a position, whether consciously or not.

Matriarchy and other stories

The title of the project refers to one of the three clans belonging to the Delaware Tribe: the Turtles, the Turkey and the Wolf. The clans are determined by matrilineal descent, which means that children are considered as belonging to their maternal grandmother’s clan. In this sense, Janssen’s photographs fall within the main goals of the Female Power exhibition: to show narratives countering patriarchal histories and highlighting alternative, matriarchal ways of remembering and preserving. The children belong to one of the three clans following the clan of their grandmothers: the link between children and their ancestors is highlighted via their clan’s name. However, this particular aspect of the Native American clans is not obvious or made totally visible within her portraits in the exhibition. It can only be understood by the spectator, once he/she has read the captions on the exhibition walls.

Janssen’s photographs are strategically positioned to highlight their connection to other works in the exhibition. For example, Mathilde ter Heijne constantly refers to stories of the “Others” in her artwork. Indeed, for Female Power, she built a replica of a house, named Export Matriarchy, which belonged to the matrilineal Mosuo community in China, and symbolized the Chinese social order. On the other side of the wall, Nina Poppe’s photographs depict the Ama, a Japanese community of women who dive to depths of up to 30 meters. The works of these artists interfere with each other, and likewise bring matrilineal power and generational patterns to the fore. Indeed, Poppe examines at the generational gap between the descendants of the Ama – young Japanese girls who do not wish to follow in their grandmothers’ and mothers’ diving practice – whereas Janssen transposes the pride and diversity of the descendants of Native Americans matrilineal clans into her portraits. All three artworks attest to the need of showing “forgotten” or misrepresented narratives, based on the emphasis of female empowerment practices and societies in which descent is traced through women. They all respond to and reinforce one another in the art space.

Cuny Janssen’s photographs are representative of the whole Female Power exhibition; her pictures tell the story of “minorities” as a counterpoint to patriarchal knowledge-construction [Bracke & Puig de la Bellacasa, 2009]. All of the artworks in the Female Power exhibition promote a new way of looking at the “self”, the body, the “Others”, and what we can learn from them. Differences are valued and alternative experiences are made visible. Thus, these artistic productions work as ‘visual’ mediators between the stories of the “Others” and the museum’s visitors. Other works in the exhibition touch upon various meanings and subjects, ranging from spirituality to ageism or racism, through subjectivity or utopia. The Female Power exhibition should be attended by visitors with an open mind, i.e. those who are able to let the art works shift their “normative” world and common beliefs. The Female Power exhibition reminds the visitor that society is culturally constructed and that artistic creativity is one of the tools to look at it differently.

Since March, the exhibition has drawn an ever-increasing number of visitors. Following the numerous reviews written in newspapers and magazines, it seems that Female Power has had a positive effect on spectators and journalists alike. The Volkskrant has described the impact of the exhibition in compelling terms: “Kunst die beroert en verbijstert“[3]. [Faasen, 2013] Moreover, the Volkskrant’s review – just as the other articles published on Female Power – contributes to the event’s overall visibility

CV

Clémence Girard did her MA degree in The Gender Programme at the Faculty of the Humanities at Utrecht University.↑

Notes

1. Lecture by Cuny Janssen] at CCA, California College of the Arts, San Francisco, November 16, 2011↑

2. ibid↑

3. Art that stirs and astound. ↑

Bibliography

Bracke Sarah & Puig de la Bellacasa Maria, “The arena of knowledge: Antigone and feminist standpoint theory”, in: Rosemarie Buikema and Iris van der Tuin (eds.), Doing Gender in Media, Art and Culture, New York: Routledge, 2009, pp. 39-53

Cuny Janssen, lecture at CCA, California College of the Arts, San Francisco, November 16, 2011. Link: http://www.cunyjanssen.nl/

Fox Keller, Evelyn & Grontowski, Christine R., “The mind’s eye”, in: S. Harding and M. Hintikka (eds.), Discovering Reality (Norwell: Kluwer Academic Publishers 1983), pp. 207-225

Faasen Jennifer, “Sterke vrouwen in power-expo” in de Volkskrant, 15 March 2013

Janssen Cuny, My Grandma Was a Turtle, Snoeck: Heule , 2010

Michael Halley, Review of Camera Lucida by Roland Barthes in Argo Sum in Diacritics , Vol. 12, No. 4, Winter, 1982

Mickeal S. Roth, Photographic Ambivalence and Historical Consciousness, in History and Theory, Theme Issue 48 (December 2009), pp. 82-94, Wesleyan University 2009 ISSN: 0018-2656

Ponzanesi, Sandra in Rosemarie & Van der Tuin, Iris (eds.), Gender in Media Art and Culture, Routledge: London, 2009

Rouillé André, La photographie: Entre document et art contemporain, Gallimard: Paris, 2005

Sentilles Sarah, The Photograph as Mystery: Theological Language and Ethical Looking in Roland Barthes’s Camera Lucida, Journal of Religion, October 1, 2010