Going Native: Besnyö’s Zeelandish Girl and the Contact Zone of Dutch Photography

Abstract

This paper introduces the concept of contact zone, as coined by Mary Louise Pratt, to explore the photographic representation of the supposed traditional Dutch population in the first half of the twentieth century. Startingpoint is a picture of a young girl that Eva Besnyö took in the village of Westkapelle in the southern province of Zeeland and published as part of a reportage in an illustrated magazine in 1940. The paper suggests that more attention should be devoted to the contacts between photographers and their models as part of the history of Dutch photography.

Article

‘When we went out to photograph some characteristic types we were initially – completely as expected – greeted with considerable suspicion.’[1] Thus writes ethnographer and photographer Jac. Gazenbeek in his contribution to the folklore photobook De Nederlandse Volkskarakters in 1938. It is a typical situation. A strange photographer meets with resistance from the people he wishes to photograph. How was this confrontation resolved?

While researching the pictorial representation of Dutch peasants in traditional attire in the periodicals and illustrated books of the Interbellum, it appeared to me how little we know about the actual conditions of the photo shoots. How did the contact between photographer and ‘local population’ develop and how can we determine what happened in the ‘contact zone’ between photographer and model? By contact zone or meeting place, I mean the social space where physical contact and cultural exchange, negotiation and struggle, took place. It is the interface where efforts to discover the Other, the Self, and possibly a feeling of communitas – the feeling of unity and connection – could be summoned.[2] The concept of a contact zone directs our attention to the social relations – including power inequality, reciprocity and negotiation – that not only determine the actual photo shoot, but also inform our interpretation of the images. Mary Louise Pratt (travel stories), James Clifford (museums) and Nicolas Thomas (photography) have introduced the concept of a contact zone and the type of questions it elicits in the study of cultural production.[3] To illustrate the kinds of questions such a perspective raises and to encourage research, I will discuss how a portrait of a girl from the province of Zeeland by Eva Besnyö comments upon the photographic practices of her contemporaries.

The photographic moment

The photographer Eva Besnyö was born in Budapest, Hungary in 1910. In 1930, she worked in Berlin, but with the rise of Hitler she decided to move to the Netherlands. There she became part of a progressive art scene centred around the family of John Fernhout, the photographer and cameraman to whom she was married. John’s mother, Charley Toorop, was a distinguished painter closely connected to numerous artists, architects and writers such as Gerrit Rietveld, Piet Mondrian and Joris Ivens. In her photography of architecture, landscapes and cityscapes, Besnyö followed the stylistic conventions of the New Photography.Yet she also went out to capture the body and face of the locals of the fishing villages and rural communities, by which she appears to prolong the topoi of the pictorialist tradition, albeit along the lines of the new conventions of style. In the years wedged between the two world wars, many more photographers on assignment ventured to capture the authentic Dutch people for posterity. Included in their photographic projects was a certain sentiment of mourning and longing for a way of life that had once existed (or so it was thought), and which, by its disappearance, had deprived the nation of a vital essence. Thus, as Besnyö put it at the time: ‘I have a special affection for [the Zeeland region of] Walcheren. Because of the kind of people who live there. I like the Walcheren farmer very much.’ Besnyö engaged in a great deal of photography on Walcheren, which was hardly surprising for someone with in-laws that had been visiting the villages of Domburg and Westkapelle regularly for years.[4]

In August 1939, Eva Besnyö photographed a girl from the village of Westkapelle, in the process of changing into traditional Zeelandish attire. After a series of images on choosing the clothing and getting dressed, Besnyö took a number of photos of her model in the open air and indoors with, what appeared to be, her family sitting at the dinner table. The photo reportage was published in the illustrated magazine Wij. Ons werk-ons leven (fig. 1) to display the local rite of passage that dressing up entailed. In 1941, three of the images would be printed in a book on traditional attire, Erfenis van eeuwen, published by the Arbeiderspers (which, by this time, had already been taken over by the German occupier).

|

Fig. 1 ‘En dan… op Paasvisite’, Wij. Ons werk-ons leven 8, 1940, pp. 18-19. Leiden University Library. |

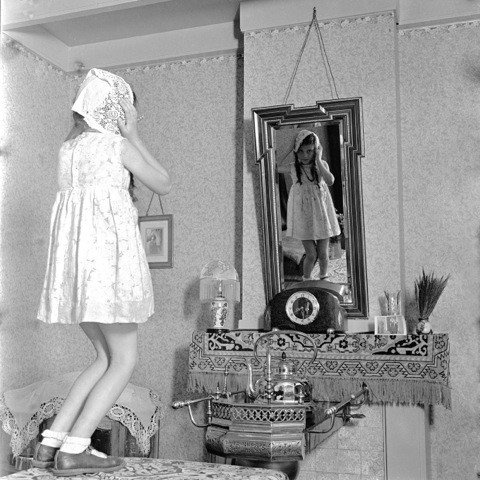

The reportage dealt with the regional dress and attire being worn and/or abandoned in Zeeland, a theme that had preoccupied folklorists as early as the 1880s.[5] Besnyö followed in the footsteps of numerous photographers that had travelled to Zeeland to photograph the attire ‘before it is too late’; yet she gave this somewhat worn-out theme of salvage photography a completely new twist.[6] This accounts in particular for one photograph (fig. 2).[7] In it we see a girl in a white dress, reflected in a mirror as she adjusts her undercap. This is the only piece of clothing on the girl’s body representative of the chaste Zeelandish attire. The girl is standing on top of the living room table in order to see herself – and using the mirror, she is also looking at us.[8] The unusual pose and the depiction of someone adjusting their clothing give the photo an intimacy that is absent in the majority of the staged photos featuring individuals or groups in traditional dress. It is as if we are observing, from a hidden position, how the girl fantasizes about growing up. But the photo is more layered than this. It depicts the place of traditional attire in growing up and in what it means to be a Zeelandish woman. The two photographs on either side of the mirror give particular expression to this latter aspect of the image. On the mantelpiece, there is a small double portrait of children in traditional attire, posing in a doorway; to the left of the mirror is a second portrait of an elderly woman in traditional dress, also taken in the open air. These photographs give the impression of, on the one hand, the significance of traditional attire’s continued usage from one generation to the next, and on the other hand, a commentary on photographic visualization in itself: does the girl take her inspiration from outsiders’ open-air photos, or from tradition itself?

|

Fig. 2 Eva Besnyö, Zeelandish Girl in front of Mirror, Westkapelle 1939. Negative, 6 x 6 cm. Amsterdam, Maria Austria Instituut, inv. no. KK.195. |

In displaying the dressed female figure of Walcheren, the reportage followed a cherished pictorial tradition. Rather amusing is the awkward way in which the girl holds the cap on her head, as well as the possibly unintentional similarity between the ‘headdress’ and the other objects in the room that have been embellished with small rugs: the chimney, the dinner table and a smaller table. At the risk of overinterpretation, it seems to me that this strengthens the artificiality of the act of ‘dressing up’, using the cap as a fetish.[9]

The picture, however, is not only about the display of traditional attire, but also about looking at someone and returning the gaze. Although voyeurism is the photographer’s conditio sine qua non, it took Eva Besnyö some time before she was ready to photograph people. In Hungary, she mainly took pictures of individuals sleeping: ‘I preferred taking photographs when I could do so undisturbed. At that time, I was too shy to impose on people.’ Besnyö stated that her ideal was ‘to be invisible, or to have a camera built into my belly, so that no one could see I was taking pictures. There are people who can work unnoticed, but I am not deft enough.’ She wanted her models to forget the presence of the camera. Even in private, ‘at home’ with Charley Toorop, Besnyö dared not to use her camera to capture the many artists who frequented the house of Toorop in the village of Bergen. After the war, it turned out that Besnyö had never shot a single portrait of Gerrit Rietveld (who was responsible for refurbishing Toorop’s house, and one of the first people in the Netherlands to praise her photography).[10] Besnyö frequently took pictures of family members and close friends, but her early photographs also reveal a certain timidity. Little is known about the circumstances in which she took her folklore portraits in the Netherlands and Hungary. She would have been granted access to her models, such as the cheese carriers of Alkmaar (whom had been painted by Toorop before) or the Volendam fishermen, either through payment or close personal relationships. The famous photo of a gypsy boy with a cello, taken early in her career, features a shot of her subject viewed from behind. Besnyö used this perspective on purpose – the cello and the long road that the boy has yet to travel are clearly visible. Although other photos of the boy and his combo exist, it is not clear whether he was aware of the moment in which he was to be memorialized photographically.

But what then is ‘the photographic moment’? If we look at a picture of our grandmother at age 24, what do we see captured there? Our grandmother back in the day? A primeval image of the woman her grandchildren can still recognize? The true Zeelandish girl or the authentic fisherman’s wife? A model posing? These were the kinds of questions that Siegfried Kracauer asked in his short essay on photography of 1927. What was ‘really’ captured was the moment the woman stood in front of the lens: ‘it was this aspect and not the grandmother that was eternalized.’[11] Besnyö has truly captured this aspect of the photographic moment in her photography of the Zeelandish girl in front of the mirror. The picture makes us aware of the presence of the photographer and the spectator as voyeurs, but it also reveals the exhibitionistic features of photography.

The attitude of Besnyö, combining timidity with a kind of voyeuristic photography, refers to a crucial aspect of photography in the contact zone. The presence of the photographer reveals his intervention in a cultural setting defined as undisturbed: the photographer not only observes, he intrudes.The intervention of the ethnographer or folklorist – and in our case, the photographer – is a recurring but unsolvable problem. It is condensed into the oxymoron of ‘participant observation’ applied by ethnographers that were sent out into the field beginning in the 1920s.[12] Is it possible or desirable to do both – participate and observe – simultaneously? The same issue was also found in folklore studies. Jos Schrijnen, the first professor of folklore in the Netherlands and the author of the first handbook on this topic, wrote in a direct reaction to the continual filming and photographing of folkloric practices carried out by his non-academic colleague D.J. van der Ven: ‘Finally, one more thing: if one wants to get closer to folklore, then one should go in person. But if one wants to capture a piece of folklore, then one should do so unnoticed (…) do not make a show of filming it.’[13] So, venture out into ‘the field’, but do so as inconspicuously as possible.The recurring conundrum is evident in the barely concealed annoyance of the photographer Nico de Haas, one of the forerunners of New Photography in the Netherlands and someone as well involved in folklore photography. Voicing disapproval, De Haas remembers that when ‘the last West-Frisian wedding’ was announced, the local council made a great song and dance, issuing invitations to photographers and folklorists. On the day itself, a grand decor made of palm trees had been erected to shield the multitude of photographers from view, ranging from amateur to professional, from ‘simple box’ to ‘8mm film camera’. In one photograph, as De Haas observed, we see a man dressed in full Frisian attire taking photos of the photographers. While De Haas noted all of this with distaste, for us this reciprocal photography is extremely interesting. In De Haas’ view, there were photographers, models and spectators: these categories were not to be confused.

The photographer observes and captures. He wants his models to look in his direction, or alternatively, to turn away from him. In achieving the poses he desires from his models, the ability of the photographer to control the photographic situation is tested: there is a power relationship inherent in photography, and the photographer does not always have the upper hand. The Flemish writer and photographer Stijn Streuvels, author of the photo book Land en leven van Vlaanderen (1926), experienced a difficult time getting his models to pose. At home, his ‘desire to direct [his children until they cried]’ was uncontrollable, but in the wider world, he was too shy and too wellknown. Wishing to portray an old woman, he gave up after a few failed attempts: ‘[h]er eyes remain averted’. For another photograph, ‘Young Cow Herds’, the young models, sadly, ‘kept looking in the lens.’[14] He was never satisfied. Once more, we see the oxymoron of participant observation: being present for the task, but being perceived as absent. The photographer wished to capture authenticity within an artificial context. The ‘model’ should be himself, should radiate authentic emotions, and in this way, especially in folklore photography, reveal his true self–but (at the same time) he should do so by ‘posing’. According to Merriam Webster, the verb ‘to pose’ means ‘to affect an attitude or character usually to deceive or impress’. In this respect, the picture of the Zeelandish girl is double-edged: it shows the authentic posture of a young girl in front of the mirror, and also reveals the process of posing on the photographer’s behalf. It is the photo shoot that has been turned into a spectacle for us. This is further reinforced by the returning gaze of the young girl. The function of the mirror is crucial. The onlooker and the photographer are both addressed by the returning gaze of the girl. The picture constructs the contact zone of photographer and model and invites the spectator to join.

Taking pictures as a transaction

The social and political status of photography changed with the introduction of hand cameras at the turn of the century. The amateur photographer made his appearance with cameras that required neither ample technical abilities nor elaborate equipment. Snapshot photography – in Dutch the eponym kiekje dates from this period – transformed our understanding of privacy in the public sphere. Photographer and writer Bill Jay has written on ‘the aggressive photographer’ as a new cultural figure that emerged with the invention of the photographique instantané, when ‘for the first time people could be photographed surreptitiously.’[15] The ‘aggressive photographer’ became a stock figure in fiction and cinematography.

The figure of the aggressive photographer directs our attention to an important caesura in the social history of photography, but unfortunately, it does present the relationship between photographer and model as one-dimensional. It underestimates the structural interdependence between photographer and model and fails to recognize common practices of exchange and transaction. Besnyö’s photo session in Westkapelle must have been achieved in such a transactional setting.

The girl in the reportage was Betje Louwerse, a butcher’s daughter visiting the Huijbregtse couple previously painted by Charley Toorop. Usually, the photographed models in this type of folklore publication remain anonymous. The model represents the collective. The photo is used as an embodied symbol of a city, region or nation; hence, neither the model’s name nor her existence as an individual was relevant to the way the photo was employed. The inclusion of such characteristics would even have distorted the significance attributed to the photo. It sometimes remains unclear whether the photographers working within this genre of folklore photography were even aware of their models’ names. In Besnyö’s reportage in Wij. Ons werk-ons leven, the girl had been named and thus given an identity, but this was not the case in the book on traditional attire, Erfenis van eeuwen, in which three of the pictures also appeared.

Walking through the local museum in 2011, a blogger from Walcheren recognized her great-uncle in Besnyö’s photo of the family seated at the dinner table. In the picture we see the family members with Betje Louwerse,who paid them a visit. The original daughter of the family (i.e. the daughter of the blogger’s great-uncle), now eighty years old, told the blogger that the photo session had made little impression on the family. The painting by Charley Toorop, however, had made a lasting negative impact because, in this painting, one of the mother’s eyes remained hidden.[16] The photo featuring Betje Louwerse, Janis and Adriana Huijbregtse and their daughter at the table, now has a place in the image database of Cultuurbehoud Westkapelle, which mentions both Eva Besnyö as the photographer as well as the names of the models. With other photographers, website credits are largely absent, indicating a reversal of power from the time of its first publication.The picture of the family at the dinner table is also part of the exhibition of the local museum (fig. 3).

|

Fig. 3 Exhibition view showing a photograph of the Huijbregtse Family by Eva Besnyö, Polderhuis, Westkapelle, 2014. Snapshot made by the author. |

These notes impinge upon our understanding of the photo shoot. We can infer the existence of rapport, of an already-existing intimate relationship between photographer and models as a prerequisite for the photo shoot. In this instance, Charley Toorop might have been the intermediary. Or, should we take the possibility of a financial transaction into account? In both instances, the favourable conditions existing in the village were crucial. Westkapelle belonged to a line of hospitable villages, places where meetings between photographers and inhabitants were regular and sometimes even routine. Artists established themselves for prolonged periods in some villages, such as the fishing townsof Katwijk, Volendam, Veere and Domburg, as well as the forest and moor villages of Hattem, Nunspeet and Laren. Westkapelle, Zoutelande and Domburg on Walcheren also enjoyed fluctuating popularity. [17] Other villages were more difficult and shunned by photographers.

Bunschoten-Spakenburg and Staphorst were interesting for their traditional attire, but taking photos in these locations was so fraught with difficulty that it was hardly enjoyable for the photographers. Staphorst was particularly infamous. When, on a Sunday morning in 1937, two women from Nijmegen took out their cameras in the village, the local youth protested. ‘Without the benefit of due process’, ‘a number of Staphorst youths seized them and threw them in a ditch’. In defence of the perpetrators, the paper mentioned that the village, ‘when emerging from Sunday morning worship’, found itself besieged by ‘at least fifty, and probably more, tourist photographers’. On Walcheren, too, the Sunday service was a popular photographic theme. In Staphorst, this popular photographic event resulted in the town council’s inclusion of a declaration in its bylaws ‘that it is forbidden to photograph anyone on or near the public road.’[18] Photographer W.F. van Heemskerck Düker succeeded in photographing the villagers of Staphorst thanks to his amicable contact with the painter Stien Eelsingh, who lived in the village. Eelsingh was a photographer’s daughter and wife and was therefore familiar with Van Heemskerck Düker’s trade. These connections ‘allowed [Van Heemskerck Düker] to take photographs in Staphorst, as long as he did not produce picture postcards of his work.’ It was his breach of this agreement that resulted in the photographer losing his privileges. He posted his photos ‘in the windows’, meaning that the images were sold in shops as picture postcards. Van Heemskerck Düker was no longer welcome in the village.[19] Elsewhere, the conversion of photos into picture postcards was common practice.

Every photographer has to deal with transcultural and transactional processes in his or her contacts with models. In addition to the strategies both parties intend to pursue, each will also bring expectations about the other’s typical behaviour into the meeting place. In the case of the photography of folklore and traditional attire, such circumstances are evident in the recurring issue of whether or not models should be financial compensated in exchange for their inclusion in portraits. The photographers appear to have held the opinion that a desired model’s refusal to be photographed was to be respected. At the same time, they disapproved of local inhabitants that offered to pose as a model in exchange for money: an arrangement that they assumed would turn authentic traditional village society into the object of a cheap gawking game.

Especially the Zuiderzee village Volendam, and to a lesser extent Arnemuiden in Zeeland, were frequently denounced for degrading themselves in this way. The ‘Volendam business’ became a concept and an abomination.[20] In Zeeland, Arnemuiden was almost as infamous as Volendam. Because of their poverty, the women there ‘tried to make a little extra on Thursdays, when there were many tourists about, going to town with their beautifully decked-out children to make some money having their pictures taken. The practice constituted veiled mendicancy, and was therefore prohibited, but it happened on a large scale. People called it going for “monnie”’.[21] This latter information is highly interesting, as it alludes to the local strategies of dealing with photographers. In this case, the photo can only be taken after the model exerts some effort in communicating about the desired transaction, while the photographer tries to avoid the financial remuneration.

The photographer’s annoyance with models ‘begging’ for money or a photo can be interpreted as the wish to maintain his authority in what seems to have been a mutual negotiation between photographer and model. Yet the matter of money was controversial in another way. It emphasised the status of the photographer as modern homo economicus.[22] This situation corresponds with the photographers’/folklorists’ annoyance over their models’acts of mimesis: by asking for money, villagers were behaving like modern photographers or tourists, while their very ‘otherness’ should lie in their aloofness from the modern economy. In short, the meaning of the demand for money was paradoxical. To the photographer, this sort of commodification obstructed the desired communitas with traditional countrymen since the latters transactional attitude revealed a rather modern habitus. The folklorist and photographer Jac. Gazenbeek, whose confrontation with unwilling locals served as the introduction to this article, included an anecdote about how the desired communitas wih a traditional representative of the nation was eventually established. As soon as the locals heard ‘that we were born in the region, the situation changed’:‘A smile slid over the face of the farmer’s wife, while she, suddenly talkative, chattered: “You’re pulling my leg, aren’t you? Then you must be this or that guy’s boy? But kid, that means I know your mother.”’Following the villagers’ initial suspicion, the atmosphere quickly thawed in the meeting place: ‘“Sit yourself down and have a cup of coffee. Plenty of time to draw the master, he’s not running away…”’[23] Not only did they speak in dialect; the participants also understood each other as members of the same social networks. Hence, ‘Plenty of time to draw the master.’

The Innocence/Culpability of the Camera

With Eva Besnyö’s picture of Betje Louwerse as my guide, I have suggested a few directions for uncovering the transactions of photographer and model in Dutch Interbellum folklore photography. Before the war, photographers went in search of the authentic inhabitants of the Netherlands, with both old – pictorialist – and new photographic conventions of style in their toolbox. In the contact zone – an artists’ village, a market or a farmyard – the photographers met with these authentic Netherlanders. And what happened next?

‘It is not justa matter of being in the street with that thing hanging around your neck and checking to see whether something is happening. It is going on a hunt… clicking a stranger in the face. But that will always be delicate, you’d better not talk about it.’[24] Photography, as presented in the words of the post-war photographer Ed van der Elsken, is a complex endeavour almost treading on a terrain that is taboo. Van der Elsken’s choice of words suggests movement,—photographer and model travel around to actually meet each other—but also a certain intensity on the part of the photographer. It is the image of the photographer as aggressor, as Bill Jay puts it.Yet I feel this is insufficiently accurate in describing the interdependent relationships that could develop, even if for only a few minutes or seconds.

Besnyö’s picture of a Zeelandish girl in front of the mirror yields a number of directional narratives about the way in which (portrait) photos were produced. Indeed, just like Van der Elsken, his colleagues did use the metaphor of the ‘hunting ground’ and, furthermore,did stress the importance of looking and observing. The photographer acts as ‘the seeing man’, such as he is described in the literature on the so-called non-conquering explorers: the man – according to custom, it is a man, although this was not always true in practice –exercises power through his all-seeing eye and explanatory pen – he watches and names, but professes his further innocence and aloofness. Besnyö’s picture of Betje in front of the mirror engages in this theme of innocuously looking and being observed. The use of the mirror, of course, inadvertently recalls the use of mirrors in the Arnolfini Portrait by Jan van Eyck and in Velasquez’s painting Las Meninas– and even more so Michel Foucault’s analysis of this latter painting. Closer to home, we might refer to the use of mirrors in the Berlin and Amsterdam self-portraits by Besnyö. In the particular case of the gaze via the mirror, Besnyö’s Zeelandish girl presents the spectator with an imaginative diagonal that is characteristic of Besnyö’s photography. But as I would argue, it also draws our attention to the (visual and social) relationships between the model, photographer and spectator.

A recurring feature of folklore photography was the photographer’s production of a limited series of images of ‘regional types’, ‘locals in traditional attire’ or ‘the fatherland.’ Specific choices that were made concerning a limited number of available locations and motifs were quite possibly specified by the client. Furthermore, we may assume that the significance of the photographic image underwent a transformation after the photo was taken. A villager known by name became a photographed type, to be used in different media, in various combinations with other photos and with different captions. Most rhetoric about the innocence of portrait photography revolves around the practices of representation in colonial situations, but in general, the comparison with the colonies is probably unjust, as it involves a different balance of power. Nevertheless, because of the transactional aspects that play a part both in capturing the model on film, as well as the model’s inability to exercise any influence over the use of the photo in which he or she appears, we can draw some parallels between the Dutch and colonial situations. In the latter, the power relationship between outsiders and the country’s ‘indigenous’ population is certain to have played a part in the transaction. Eva Besnyö’s picture and the photo shoot belong to this genre, but also present us with a reflection on the processes involved with ‘going native’ and watching the ‘natives’ from outside. In her reportage, Besnyö photographed the importance of attire as an identity marker and a rite of passage in the local community, as an admission ticket to enter an indigenous family, as well as an indispensable device to blend in with the local landscape. The picture hinges on the articulation of collective and personal identity that the wearing of traditional attire implies. The picture furthermore comments upon two common ways of looking at photography; as the result of a transaction or as the result of an affective rapport. As a double-edged sword, Besnyö’s picture exemplifies the concept of dressing up culture: its thin, often indefinite, boundaries between the public and private sphere, and between authentic local culture and a posing ‘culture’ for outsiders.[25]

CV

Remco Ensel (1965) teaches history at the Radboud University Nijmegen and is affiliated with the NIOD Institute of War-, Holocaust- and Genocide Studies. In 2015, his monograph on photography and nationalism in the first part of the 20th century (De Nederlander in beeld. Fotografie en Nationalisme tussen 1920 en 1945, 2014) will appear in an English translation. Earlier publications include a monograph on representations of white-collar life in literary and visual culture (Alleen tijdens kantooruren. Kleine cultuurgeschiedenis van het kantoorleven, 2009), and the article ‘Dutch Face-ism. Portrait Photography and Völkisch Nationalism in the Netherlands’. Fascism. Journal of Comparative Fascist Studies 2,1: pp.18-40.↑

Notes

1. Gazenbeek 1938, p. 119.↑

2. Turner 1974, p. 169.↑

3. Pratt 1991, pp. 33-40: ‘I use this term to refer to social spaces where cultures meet, clash, and grapple with each other, often in contexts of highly asymmetrical relations of power, such as colonialism, slavery, or their aftermaths as they are lived out in many parts of the world today.’ See Clifford 1993; Thomas 1994; Mitchell 1988.↑

4. ‘Zeeuwsche vrouwen’, Het Vaderland,12 August 1940; the reference to the N.R.C. comes from Vlissingsche Courant, 4 November 1940.↑

5. A similar intervention, yet in reverse, can be attributed to a video that caused some uproar in 2004. Paul de Nooijer and Menno de Nooijer created a ‘Stripshow 1850’ for the Zeeuws Museum. In the video, we see a young man and a young woman undress to show the layers of traditional attire: See YouTube: http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=p690WNukbOQ (Accessed on 1 May 2014).↑

6. On the ‘(false) sense of urgency’ implied in salvage photography see Croft 2002, p. 20.↑

7. Signature: MAI EB KK 195.↑

8. See Besnyö, De Vries and & Louwerse 1990.↑

9. This has been captured in the photograph Shopping Bag by Hendrik Kerstens (2008), which shows a young woman with a plastic shopping bag as a headcap from Zeeland on her head.↑

10. ‘Rietveld over Eva Besnyö’, De Tijd, 27 November 1933.↑

12. DeWalt, K.M. and B.R. DeWalt 2011, Participant Observation: A Guide for Fieldworkers. Lanham, MD.↑

13. Schrijnen 1930, pp. 23-4.↑

14. Coppens, Van Deuren and Thomas 1994, pp. 41-43; Ensel 2009.↑

15. Jay 1984; Philips 2010.↑

16. Besnyö, De Vries and Louwerse 1990; Blog http://lupineke.blogspot.nl (Accessed on 1 May 2014) (‘Eva Besnyö in Westkapelle-deel 1, II, 17 April and 25 April, 2012)↑

17. See Bodt 2004 and Krul 2007.↑

18. ‘Fotografeeren zonder toestemming verboden te Staphorst’ (‘Men schrijft aan het Alg. Handelsblad’ from Zwolle, 24 November 1937), Eigen Volk, IX, 1937, p. 280.↑

19. NFA HDK: documentation folder Heemskerck Düker: interview with Mrs Atie van Heemskerck Düker, 8 January 1999 [interviewer Flip Bool] and interview with Mrs Atie van Heemskerck Düker-Bakker, 31 January 1997 (I corrected the orthography of the name ‘Eelsing’ in the quote).↑

20. Roodenburg 2002, p. 177.↑

21. De Bree and Van Ham 1975, referencing photo 58. ↑

22. The term homo economicus harks back to classical economics and liberalism from Adam Smith, John Stuart Mill to Vilfredo Pareto.↑

23. See on Gazenbeek: http://www.gazenbeekstichting.nl/ (Accessed on 1 May 2014).↑

24. In the words of Ed van der Elsken, froman interview with Ingeborg Leijerzapf in Barents 1979, p. 124.↑

25. See for an astonishing present-day example of ‘dressing up culture’ and the relationship between photographer and model the short documentary Framing the Other by Ilja Kok and Wilma Timmers (2011).↑

References

Barents, E. 1979, ‘De G.K.f.-fotografen’, in: E. Barents (ed.), Fotografie in Nederland, 1940-1975. ’s Gravenhage, pp. 16-90.

Beckers, M. and E. Moortgat 2012, Eva Besnyö 1910-2003. Budapest-Berlin-Amsterdam. Berlijn.

Bennekom, J. van 1993, ‘Met een boodschappentas loopt Eva Besnyö alles voorbij’, Trouw, 18 November 1993.

Besnyö, E., J. de Vries and J. Louwerse 1990, Eva Besnyö. Zeeland toen. Middelburg.

Bodt, S. de 2004, Schildersdorpen in Nederland. Warnsveld.

Bree, J. de and J. van Ham 1975, Walcherse klederdrachten. Middelburg.

Clifford, J. 1975, Routes: Travel and translation in the late twentieth century. Cambridge, MA.

Coppens, J., K. van Deuren and P. Thomas 1994, Stijn Streuvels. Fotograaf. Gent.

Croft, B.L. 2002, ‘Laying ghosts to rest’, in: E. Hight and G.D. Simpson (eds.), Colonialist Photography:Imag(in)ing race and place. London/New York, pp. 20-29.

DeWalt, K.M. and B.R. DeWalt 2011, Participant Observation: A Guide for Fieldworkers. Lanham.

Diepraam, W. 1993, Een beeld van Eva Besnyö. Amsterdam.

Ensel, R. 2009, ‘Lunkgaten. Stijn Streuvels als geheugenfotograaf,’, in: T. Sintobin, M. de Smedt, J. de Smet and H. Vandevoorde (eds.), Voor altijd onder de ogen: Streuvels en de beeldende kunsten. Stijn Streuvelsgenootschap Jaarboek 14, pp. 90-105.

Foucault,M. 1971, The Order of Things: An archaeology of the human sciences. New York.

Gazenbeek, J. 1938, ‘De Veluwenaars,’ in: A. de Vries and P.J. Meertens (eds.), De Nederlandse Volkskarakters. Nijkerk, pp.105-122.

Jay, B. 1984, ‘The photographer as aggressor. When photographer became a moral act.’, in: D. Featherstone (ed.), Observations. Essays on documentary photography. Carmel, CA, pp. 7-23.

Kracauer, S. and T.Y. Levin 1993, ‘Photography’, Critical Inquiry 19, 3, pp. 421-436. Original: ‘Die Photographie’, FrankfurterZeitung, 28 October 1927.

Krul, W. 2007, ‘Oorsprong, eenvoud en natuur. De bloeitijd van de kunstenaarskolonies, 1860-1910’, BMGN 112, 4, pp. 564-584.

Mitchell, T. 1988, Colonising Egypt. Berkeley, CA.

Philips, S.S. (ed.) 2010, Exposed. Voyeurism, surveillance and the camera. London.

Pratt, M.L. 1991, ‘Arts of the Contact Zone’, Profession 91, pp. 33-40.

Roodenburg, H. 2002, ‘Making an Island in Time: Dutch Folklore Studies, Painting, Tourism, and Craniometry around 1900’, Journal of Folklore Research 39, 2-3, pp. 173-199.

Ruiter, T. de 2007, Eva Besnyö. Leiden.

Ruiter, T. de and C. de Swaan 1982, Eva Besnyö: ’n Halve eeuw werk. Amsterdam.

Schrijnen, J. 1930, Nederlandsche Volkskunde. Zutphen.

Thomas, N. 1994, Colonialism’s Culture: Anthropology, travel and government. Princeton, NJ.