Early Advertising Photography in Belgium and the Netherlands: a Preliminary Overview

Abstract

A whole class of photographs, including some of the most inventive imagery of the nineteenth century, was thrown away almost as soon as it was created. Advertising photography, although recognized from the beginnings of the medium as a potential revenue-earner by many professional photographers, was little regarded at the time and taken for granted by the business community that commissioned the work. Consequently, very little has survived, except for some trade and auction catalogues illustrated with photographs. Despite the paucity of original artefacts, a preliminary overview is attempted, by means of examples drawn from a wide range of products and services and in a variety of formats (from small insert cards to full-plate display prints). These examples are of Dutch or Belgian origin, whenever readily at hand, and are otherwise drawn from neighbouring countries. Photographers applied some of their most imaginative designs to advertise their own goods and services. The origins of the fascinating relationship between commerce and its reproducible image, from simple visual statements to complex branding, are worthy of further research.

An historiographic enigma

‘The feeble beginnings of whatever afterwards becomes great or eminent are interesting to mankind.’[1] Thus the foremost musicologist of his era, Charles Burney, opening his four-volume history of music with a defence of the historian’s method. The same might well be said about the unheralded beginnings of advertising photography, which at first sight seems to have emerged, somewhat feebly, in the nineteenth century to the general indifference of contemporary commentators, archivists and librarians. When Robert Sobieszek, the then Director of Photographic Collections at George Eastman House, published his groundbreaking study The Art of Persuasion: A History of Advertising Photography in 1988, he was clearly hampered by the absence of extensive archival material – no substantive holdings of advertising photography predating the 1920s were at hand and whatever primary artefacts or secondary texts he could locate were few and far between. In a two-hundred page book, the first eighty years are covered in 14 pages,[2] and the author was able to restate as fact the commonplace belief that ‘photography played only a minor role in advertising for nearly a century after its invention.’[3] Of course Sobieszek was writing in an era before search engines made the location of embedded literature or the obscurest of references mere child’s play, and before internet auctions sites such as e-bay acted as aggregators for all manner of collectibles.

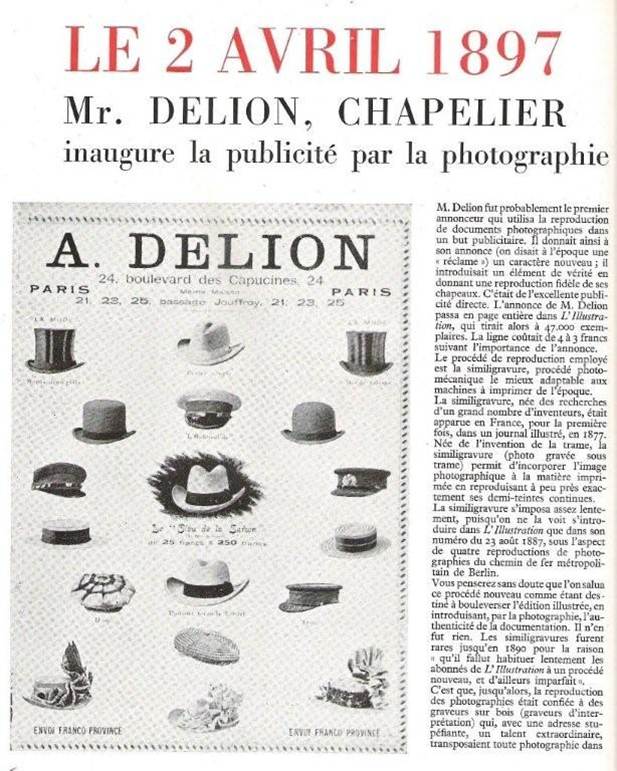

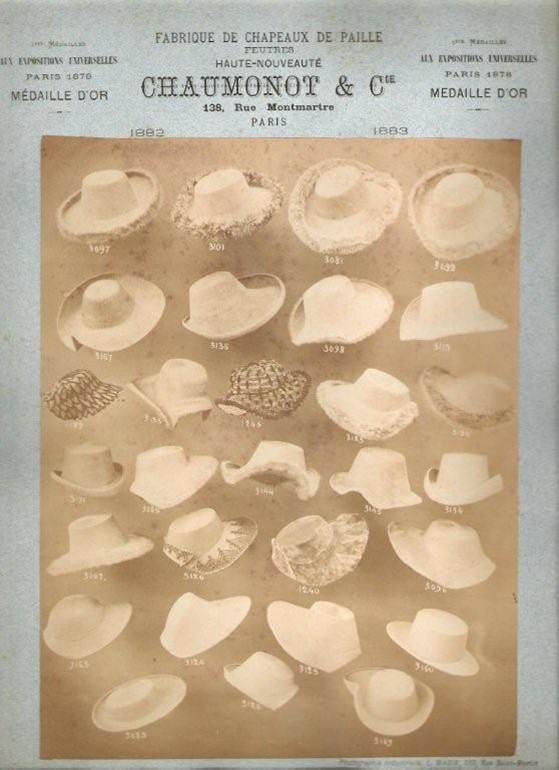

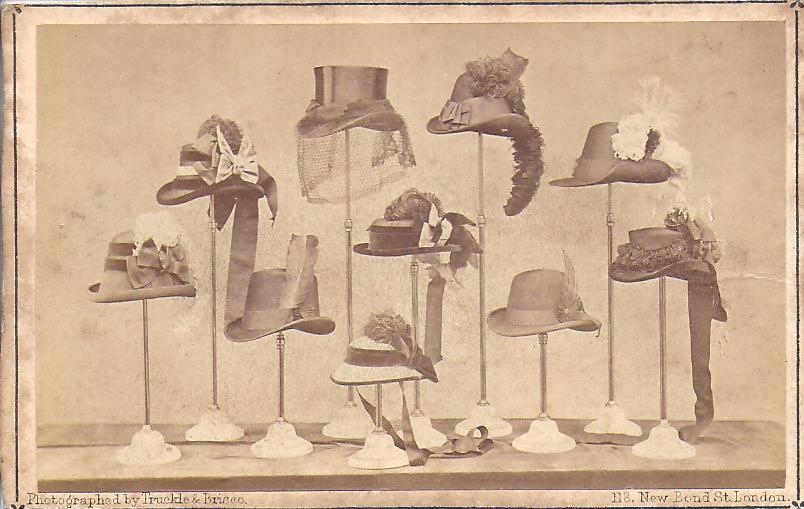

The lack of historical perspective generally marks twentieth-century accounts of advertising photography like the grin of the Cheshire cat in Alice in Wonderland, the disappearance of which prompts Alice to remark that she has often seen a cat without a grin but never a grin without a cat. A standard French study, La photographie publicitaire by Lorelle and Langelaan, published in 1949, is typical. The authors date the birth of advertising photography very precisely – to the day, in fact, when a Parisian hatter gave (according to the authors) ‘a new character…an element of truth to his hats’[4] in the weekly publication L’Illustration (fig. 1). It may have been the first full-page advertisement in halftone in that particular periodical, but this hardly constituted a novelty in any broader sense. Fourteen years before, you could have admired a similar fine display of straw hats, also in Paris (fig. 2). Or, winding back the clock another decade or so, a London milliner of the 1870s brought together a collective show of ladies’ headwear on stands, offering, on the verso, to send ‘sample hats…on approval to any part of the United Kingdom’ (fig. 3). Iconographically, the biblical assertion that there is nothing new under the sun rings loud and clear.

|

Fig. 1: ‘On 2 April 1897, Mr Delion, a hatmaker, inaugurates advertising by photography.’ Lorelle and Langelaan 1949, p. 6. |

|

Fig. 2: L. Marix, Paris, Chaumonot & Cie, Fabrique de chapeaux de paille. Albumen print, full plate, 1882-1883. Private collection. |

|

Fig. 3: Truckle & Brisco, London, Items by an unidentified milliner, ca. 1872. Albumen print, carte-de-visite. Private collection. |

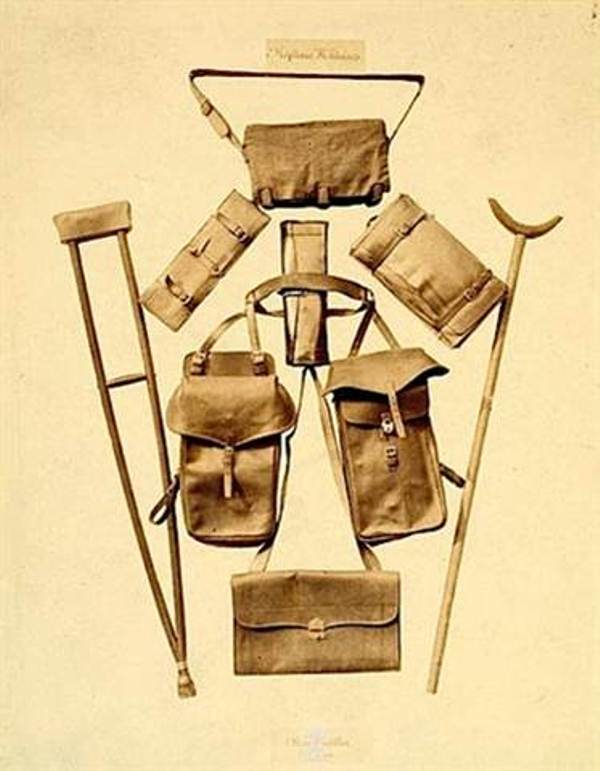

Now, when we look into public holdings of photographic imagery put together in the twentieth century, there does appear to be a marked reluctance to give early advertising its due. Too frequently an otherwise well catalogued entry (date, process, size, source accurately stated) will omit the purpose of the image concerned, thereby depriving the image of its original context and rendering it impossible to undertake a keyword search using ‘advert’, for instance. This is not to belittle the work of modern-day curators or question their integrity. So many items enter museums divorced from the context of their making, so that curators often have an uphill task to reconstruct the original meaning of a work or set of images. This decontextualisation of many museum-based artefacts may on occasion be reinforced by another phenomenon, a readiness to leave the mercantile purpose of much photography implicit rather than spelling it out. This blind spot was certainly prevalent in the nineteenth century when the medium was striving to win its artistic spurs in the face of considerable snobbish resistance. In 1861, Alfred Briquet contributed two large frames of prints to the French Photographic Society’s fourth exhibition.[5] Most of the prints featured military equipment, artfully arranged like this army surgeon’s kit (fig. 4). The catalogue fails to offer the essential information that the series was commissioned by the manufacturer Alexis Godillot, official supplier to the army under Emperor Napoleon III. It would be left to visitors to the exhibition to make the link for themselves. Only in the bound album is the salient characteristic of the series made explicit, thanks to a photographic title page displaying a broad sample of Godillot’s equipment and uniforms. Advertising photography thus shared the marginal status accorded to much graphic output which was not avowedly artistic in intent.

|

Fig. 4: Alfred Briquet, Paris, Military equipment manufactured by Alexis Godillot. Albumen print, full plate, 1861. Private collection. |

The avid researcher needs to burrow deep into collections away from the mainstream of photo-history to get some idea of the type and range of photographs in nineteenth-century advertising. This is because long before they were collected as photographs, they were being collected as examples of ephemera, aptly defined as the ‘minor transient documents of everyday life.’[6] The British Library in London houses some 5000 items from the Evanion collection, acquired in 1895.[7] Assembled as ephemera, the collection includes many flyers and handbills that once circulated in enormous quantities through the streets of large cities, wherever the arteries of commerce flowed most vigorously, including a dozen or so examples from the field of photography. Amongst the collection’s glories are chromolithographic posters and handbills produced for the various entertainments staged in music halls, theatres and other places of public entertainment. These include a poster or show card produced for fixed display outside the Grecian Theatre, well-known in 1870s London for the production of melodramas, incorporating four mounted albumen prints featuring scenes from the play Hand & Glove.[8] A manuscript inscription helpfully informs us that the broadside was produced for a performance on Saturday, June 20, 1874. This public use of photography was by no means new; it had attracted the attention of The Photographic News, one of the very first specialist magazines published for British practitioners, back in 1859. An anonymous commentator observed: ‘It is not an unusual thing to meet, in the course of one’s perambulations, with photography as an advertising medium. It seems to be an especial resort now of showmen and theatrical characters.’[9] He goes on to compare favourably the reception given to the new medium with traditional processes: ‘We have made inquiries as to the result of these photographic advertisements, and we are informed that they much surpass the old method of advertising by lithographs, which, however well executed, left only the impression on the public mind of an ideal; whereas, by having photographs taken, they see the real[…].’ And what was good for London, probably held true in Paris, Brussels, Amsterdam and other European urban centres. However, faced with a lack of specialist secondary literature or contemporary commentary, only the fortuitous survival of original artefacts would assist in resolving this historiographic enigma.

Definitions, taxonomy and classification

There are other, more subtle reasons why much early advertising photography has until now slipped beyond academic scrutiny. First, there is the matter of labeling, of the naming of the act. For us the term ‘advertising photography’ seems self-evident. In its narrowest sense, advertising is the act of drawing public attention to a product, service or need with a view to persuasion, usually for facilitating a potential commercial transaction. Photography is therefore a support or medium of choice by which to draw attention and persuade. But before there was any specialization, the professional photographer was a jack-of-all-trades. Advertising photography, not granted the dignity of separate status, often occupied an undefined space between genres, with all the attendant ambiguities for posterity’s understanding of it. In fact, lack of definition seems to have led automatically to neglect, so that the genre failed to partake in the virtually universal tendency to collect and hoard.

In fact, advertising photography enjoyed a steady if unspectacular existence over the course of the last third of the nineteenth century. Practitioners were known as commercial or industrial or business photographers, thereby distinguishing them from the general run of studio and portrait photographers, although the two fields could often overlap, as this back mark attests (fig. 5). Even the use of photography as advertising matter in magazines or serial publications was nothing new. Whether transformed into lithograph or wood engraving or, less frequently, mounted directly, photography had a long history in the press (fig. 6). This example, from a display album aimed at the Belgian tourist trade, is a lucky survival. Other, similar advertisements may well appeared in the press but were just as likely to be disposed of, since advertising sections were usually discarded when the issues were bound up in annual volumes, and therefore few examples survive.

|

Fig. 5: J. Jacob, Chaumont, verso of portrait image. Lithographic text, carte-de-visite, c. 1875. Private collection. |

Second, if advertising photography was innovative in combining a behaviourally-based process with a new reproductive medium, it often remained an awkward phenomenon to classify. The Belgian patent literature tended to overlook it, while English patent literature ‘class 98 – photography’ is silent on the matter of advertising. But the picture is different if we refer to ‘class 3 – advertising and displaying’. Starting in 1855 and over the course of the following 50 years, some 100 patents cover uses of photography in advertising.[10] Very few, it is true, relate to the nature or categories of advertising photography per se. As a genre, it appears to be considered pretty much a commonplace and therefore not subject to patent protection. So the great majority of relevant patents for invention concern the display of pictorial or pictorial statements, including but not exclusively for photography.

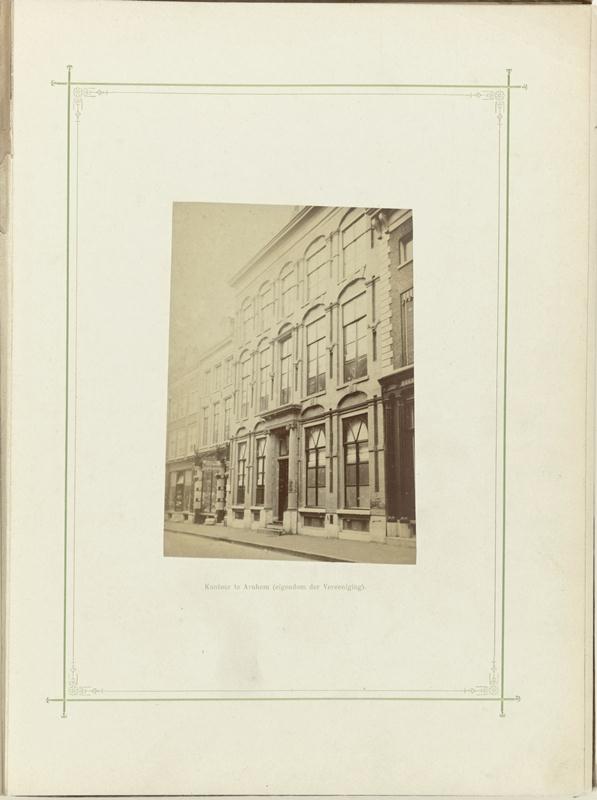

Finally, the near invisibility of early advertising photography is linked to an ambiguity of purpose in the very act of picture-taking, blurring the boundaries between the private and the public spheres. How should we read this portrait (fig. 7)? It may be a private shot to record participation in a festival procession or party, but it could well have had a broader, more commercial purpose and been disseminated accordingly. A neutral and rather banal architectural view requires knowledge of the context for the viewer to appreciate its true purpose as part of a promotional publication marking a financial institution’s silver jubilee (fig. 8). The overlapping of genres was taken for granted in early photography, when there was no pronounced stylistic difference between an image made with a view to marketing or for private purposes only. The accompanying graph presents this ambiguity of status in schematic form.

|

Fig. 7: Photo Viennoise, Blankenberghe, Woman wearing ribbons advertising the newspaper Le Petit Bleu, Brussels, ca. 1900. Print on printing-out paper, elongated cabinet format. Private collection. |

An early attempt at classification was provided in a lecture given in Manchester, the British hub of the industrial revolution, in 1856. The Reverend W.J. Read, in a paper presented to the Manchester Photographic Society, sub-divides what he calls ‘the Commercial applications’ into three categories: ‘a) the illustration of Works in Progress, b) depicting Machinery and c) Finished Wares’. In the latter category, he presents the example of ‘some Coachmakers, and Birmingham and Sheffield manufacturers, [who] have begun to employ [photography] to shew [sic] what are the works they turn out, using them instead of the often ill drawn perspectives which fill so many advertising sheets.’[11]

New ways of showing and selling

Around this time, when infinitely reproducible paper photography was finally imposing itself over the one-off Daguerreotype, the general as well as the specialist photographic press contains occasional references to the use of photography as an advertising medium. This was a first wave of recognition that advertising photography had the potential to become a major source of business for professional photographers, particularly in major urban areas. Gilbert Radoux, a French political exile, set up the first photographic printing works in Brussels in 1857. He foresaw that the future of photographic printing lay in appealing to and satisfying the needs of commerce: ‘Bronzes, jewellery, ceramics, fabrics and ivories, depend more or less on photography which alone can give a faithful and precise reproduction to scale. This is an advantage over drawing and engraving, which can only give a rough likeness. The main industrial firms in the capital have already applied to Mr Radoux; photographic samples of their finest wares are of an inestimable advantage, and ease considerably commercial transactions.’[12] No corroborative evidence of the article’s statements is forthcoming, since trade albums and literature were not deemed worthy of preserving and were therefore not covered by legal deposit provisions. We must take it on trust that Belgian manufacturers and traders used Radoux’s skills to advertise their wares.

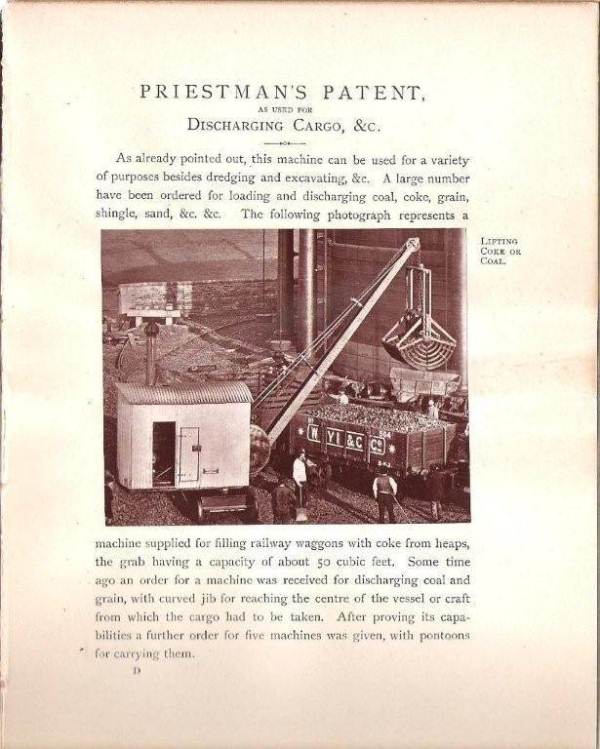

Once the novelty of photographs in advertising had worn off, by the mid-1860s, secondary sources tend to dry up. It was not until the very end of the nineteenth century that the specialist press would again take systematic notice of advertising photography. References in the intervening decades tended to be of a purely utilitarian nature. Thus, as soon as photomechanical printing had gained a foothold in the 1870s, rival firms of printers competed to attract business clients. Typically, the Woodbury Permanent Photographic Printing Company, London, asserted: ‘The value of photographic prints in trade catalogues is becoming well known and appreciated, picturing, as they do, every detail in a way unattainable by any other mode of production.’[13] The firm then lists work done and available for viewing in their offices – furniture, textile fabrics, engineering models, buildings, ceramics, metal work. However, like last year’s telephone book or mail-order catalogue, the trade catalogues of yore were destined to lead a brief and much thumbed existence before being unceremoniously dumped. None are listed in collections of the British Library; the example shown here, from a private collection, elsewhere appears in the holdings of a single UK public institution, the University of Glasgow (fig 9).

|

Fig. 9: Unidentified photographer, one of 15 prints in: Priestman Brothers, The Priestman dredger, excavator, and elevator, Hull/London 1882. Woodburytype, 84 x 104 mm. Private collection. |

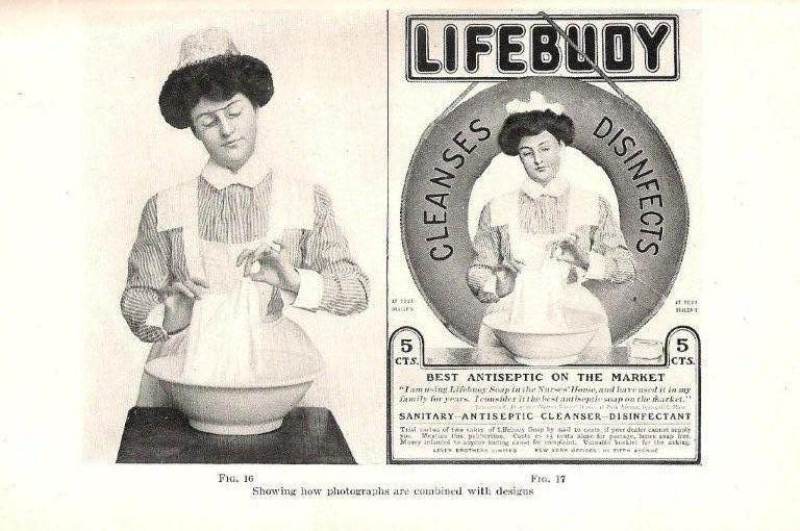

The mercantile spirit which reigned in the northern United States of America led to advertising photography first being systematically set out and formulated there towards the turn of the twentieth century. The earliest text books appeared there, such as Photography in Advertising by Joseph A. Adams, published in the ‘Photo-Miniature’ series in 1904 (Adams, 1904). The appeal had broadened beyond the professional community, and amateurs were encouraged to create work which could be supplied to advertising agencies. The gradual change in visibility of the genre was due to a confluence of innovations which can be read in these examples drawn from Adams’ work (fig. 10): first, the half-tone revolution, which was helping to disseminate more visual-based advertising of all sorts than ever (and not just photography), especially through the medium of large circulation magazines; second, the rise of the graphic artist to frame and enhance photographic imagery (although the term “graphic design” was only coined in 1922); and third, the growth in branding of mass-market consumer goods, so that ‘the photograph enters into every well-considered scheme of publicity.’[14]

|

Fig. 10: ‘Showing how photographs are combined with designs’. Adams 1904, facing p. 156. Private collection. |

Product and image types and spread

I have been tracking and collating examples of pre-1914 advertising photography on the web for the past ten years, and have been able to build up a database of over 2000 entries. Although the following observations are of a general import, they apply equally to production from the Low Countries. The leading categories are for consumer goods: medical and health supplies, clothing, and food and drink collectively account for over one quarter of all entries. Health-giving hair-tonic, dirt-defying soap, exotic oil for curing deafness, complexion soap for bonny babies, indicate the range of imagery deployed to entice female consumers in particular. The snake-oil merchants were not averse to exploiting the retouched image, as in these before-and-after portraits for skin cream (fig. 11). From the mid-1870s, they support a very early campaign with multinational ramifications, as the advertising matter exists in Spanish as well as in this French version.

|

Fig. 11: Unidentified photographer, Maison Candès et Cie, lait antéphélique, Paris, ca. 1875. Woodburytypes with two-tone lithographic background and text, 83 x 61 mm each. Private collection. |

Moving on to clothing, the proud shopkeeper in front of his storefront is a common trope in early advertising, suitable for appealing to a local clientele. The latest fashions could be instantly disseminated throughout the country, and in a composite form proper to photography, in this case with a humorous presentation of headgear for the crowned heads of Europe (fig. 12). One particularity of nineteenth-century advertising photography is the widespread use of dolls and stuffed animals. The Brussels-based César Mitkiewitz produced this particularly well-posed image of a stuffed monkey as cook to advertise a local producer of stoves and flues (fig. 13) in the late 1860s.

|

Fig. 12: Unidentified photographer, Les Chapeaux Basile, Brussels, artwork signed Kossuth, ca. 1905. Halftone print, postcard. Private collection. |

|

Fig. 13: César Mitkiewitz & Cie, Brussels, Delaroche, fabricant de coffres-forts…poëles et cheminées, ca. 1868. Albumen print, carte-de-visite. Private collection. |

|

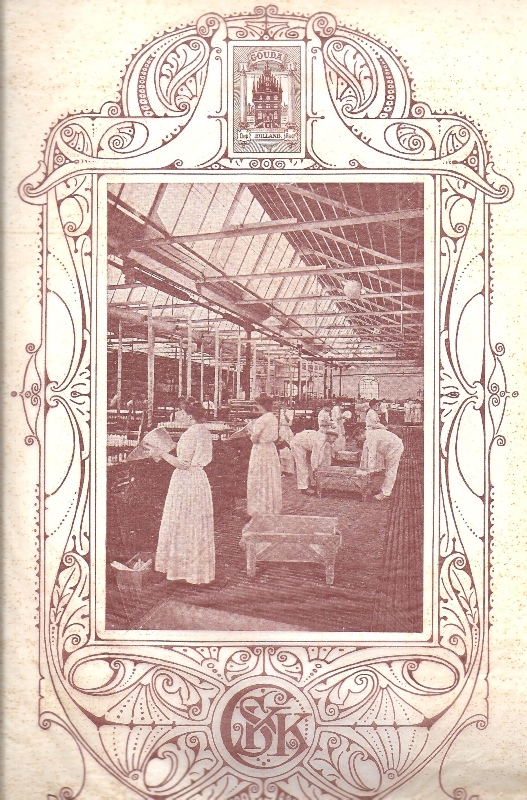

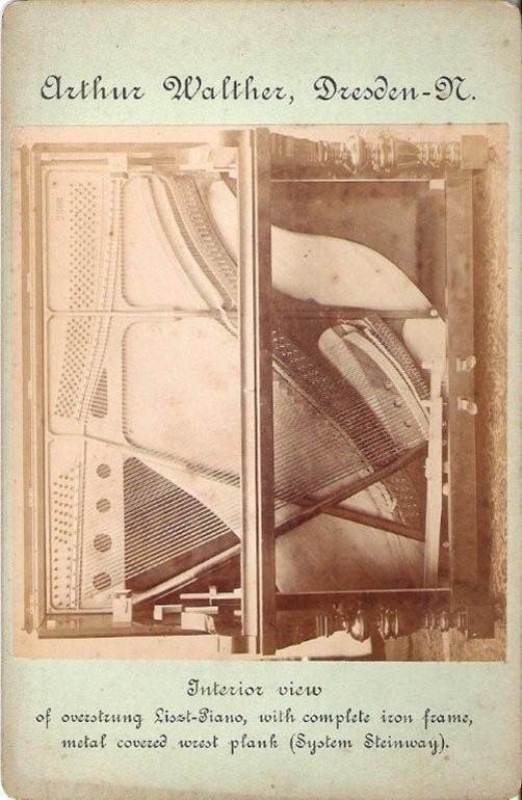

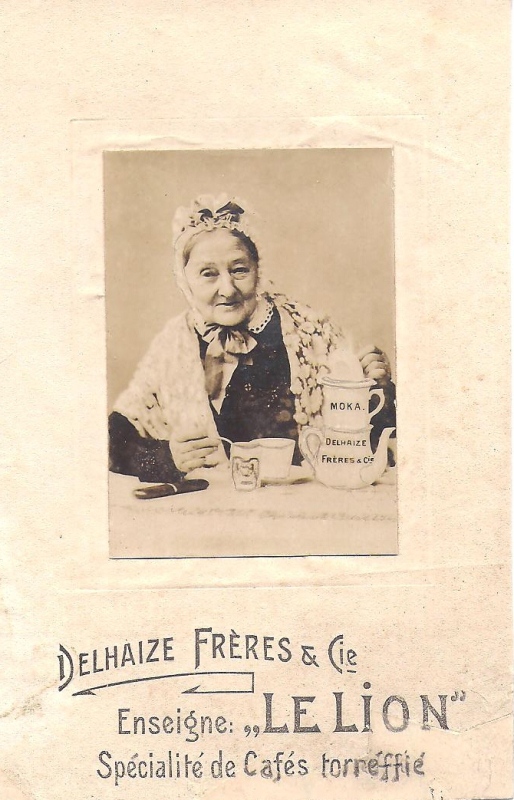

Fig. 14: Unidentified photographer, Arthur Walther, Dresden-N. Interior view of overstrung Liszt-Piano, ca. 1890. Albumen print, cabinet. Private collection. |

The direct use of an unadorned object in a spare studio setting was common and might seem overly naive to our media-saturated eyes. But more sophisticated use of photography was frequent if not universal, such as this imaginative view of the innards of a Steinway piano (fig. 14). Dutch consumer producers were amongst the first to go in for consistent branding via the use of photography. Many types of comestible were marketed with insert cards, otherwise known as weggevertjes (literally ‘give-aways’) or plaatjes (‘little pictures’). ‘Human interest’ or ‘atmosphere advertising’ was often cited by early commentators as an element to be included in publicity campaigns. Thus, many photography-based campaigns, rather than featuring the goods and services they were selling, made a frank appeal with winsome children, sometimes hand-coloured for greater impact (fig. 15). For another campaign, also involving a young girl, the photographer used his own full-plate camera as one of several studio props (fig. 16). In contrast, a rare Belgian image for coffee appears less sophisticated and more literal in its presentation (fig. 17). One further step in marketing consisted of issuing albums to house the insert cards. One Dutch cheese manufacturer interspersed leaves for the insert cards with views of the manufacturing process aimed to demonstrate the modernity and efficiency of factory food processing (fig. 18).

|

Fig. 15: Unidentified photographer, Kraepelien & Holm’s Tamarinde-Bonbons, ca. 1910. Hand-coloured bromide print, insert card. Private collection. |

|

Fig. 16: Unidentified photographer, “Grootes”, cocoa and chocolate, Westzaan, c. 1910. Bromide print, insert card. Private collection. |

|

Fig. 17: Unidentified photographer, Delhaize Frères & Cie, spécialité de cafés torrifiés, [Brussels], c. 1910. Albumen print, insert card. Private collection. |

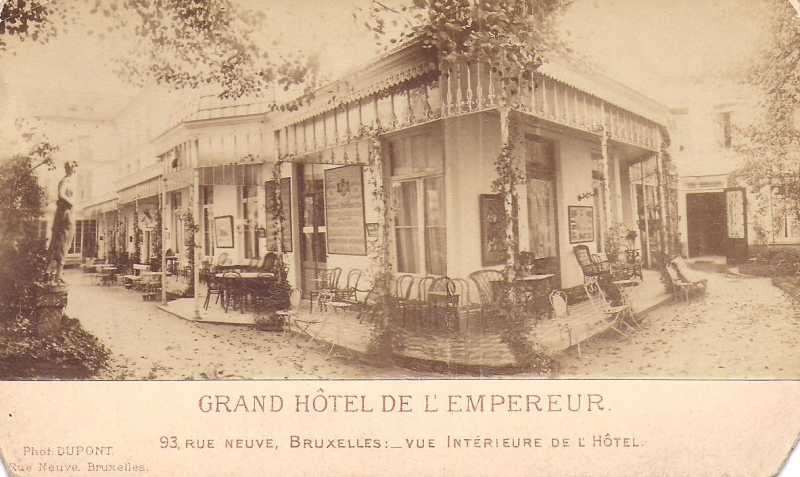

Other significant categories of goods and services comprise architecture and construction, and hotels and tourism (fig. 19). Also present in significant numbers are department stores, machine tools, furniture and horse-drawn vehicles. In the light of Belgium’s entering the period of industrial development earlier than its continental neighbours, a number of trade catalogues were issued there in the field of railway locomotion (fig. 20) and military equipment (fig. 21), in common with Britain and the United States similarly in the throes of the industrial revolution.

|

Fig. 19: Dupont, Grand Hôtel de l’Empereur, Brussels, c. 1890. Albumen print, cabinet. Private collection. |

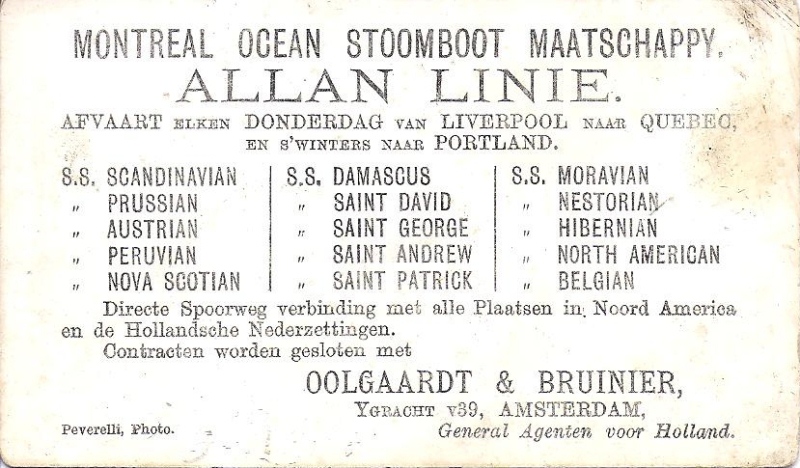

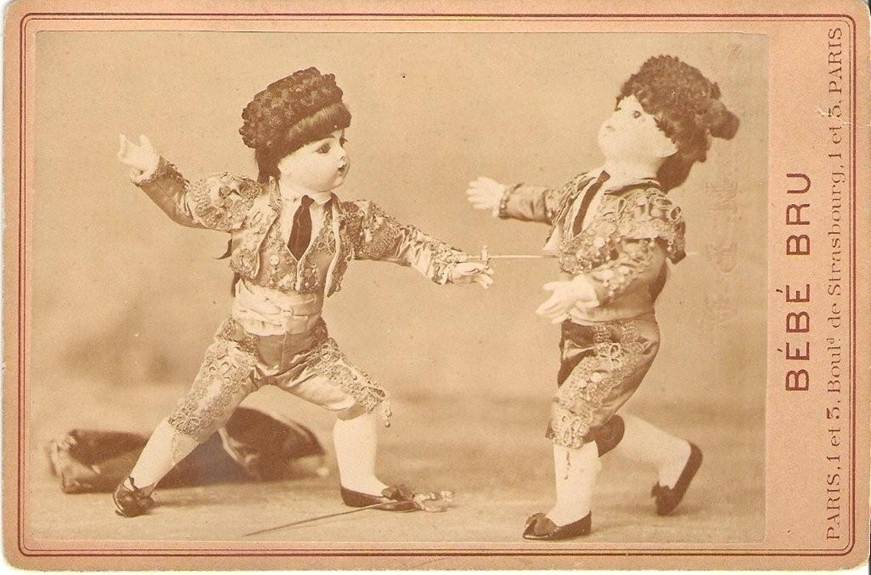

Concerning the geographical spread in the database that I am creating, in all of the categories surveyed, with the exception of hotels, American goods and services form the majority, and usually outnumber items from Europe and elsewhere in a proportion of 2:1. Statistically, I doubt that this is a simple result of source bias, arising from the current item locations. Already in the nineteenth century, the greater role of advertising in the United States was recognized, as this 1874 citation indicates: ‘In such a go-ahead nation as the United States, it is only natural that advertising should be a very important feature of its business arrangements.’[15] In retrospect, it makes academic sense to count photography among the advanced marketing and promotion techniques which so impressed non-Americans of that era. There are a couple of exceptions which prove the rule. Among Dutch and other European shipping lines, the use of cartes-de-visite giving details of vessels and schedules was common (fig.22a, 22b). In France, Bébé Bru was the Barbie doll of the late nineteenth century. Just as Ken got caught up in the space race and became an astronaut in 1960s America, so Bébé Bru donned a matador’s cape when the fashion for all things Spanish swept Paris (fig. 23).

|

Fig. 22a: Peverelli, Oolgaardt & Bruiner, Amsterdam, Montreal Ocean Stoomboot Maatschappÿ, Allan Linie, c. 1880. Albumen print, carte-de-visite. Private collection. |

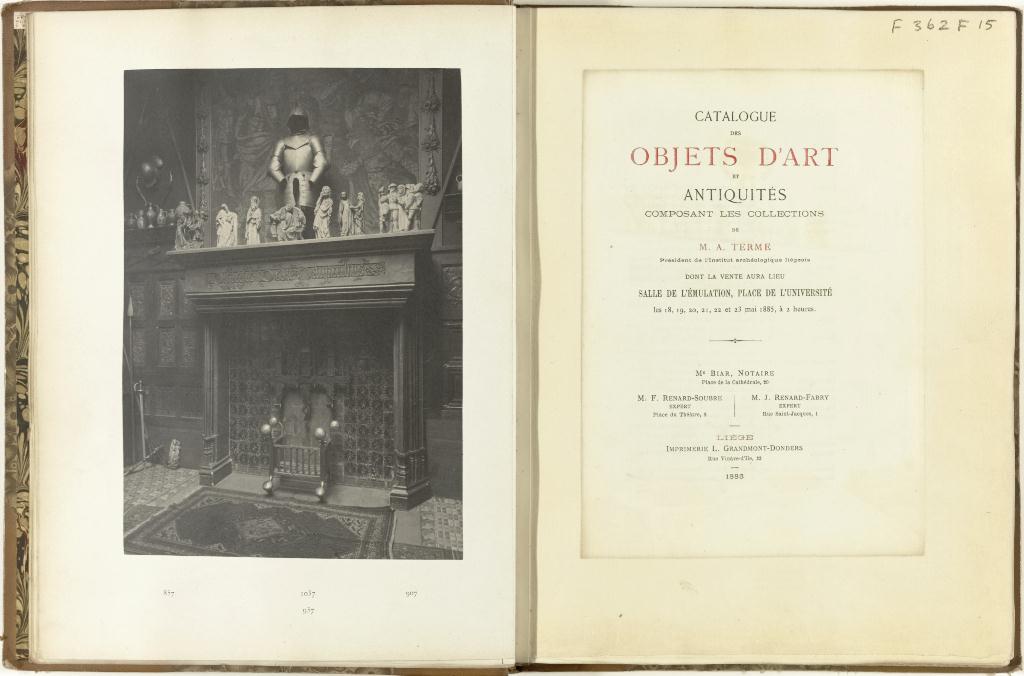

In the matter of formats, portability was the essential characteristic for advertising consumer goods. The standard photographic size of carte-de-visite and (in the United States but not Europe) the stereograph were spread evenly from the mid-1860s until the end of the century. The cabinet card, on the other hand, is virtually exclusive to the 1880s and 1890s, principally used to advertise medical supplies and clothing. The verso of the print would generally contain text extolling the virtues of the featured products. In the first decade of the twentieth century, both carte and cabinet cede precedence to postcards, which may be bromide-based (‘real photo’) or photomechanical. Two other formats were also frequently used. The photographically illustrated trade catalogue was used mainly for industrial rather than consumer goods, such as the railway locomotives shown above at figure 20. A large proportion of Belgian auction catalogues were also issued in photographically illustrated editions to serve a market that was particularly advanced in the fields of fine-arts and antiques (fig. 24). Finally full-plate and larger display boards were frequently used to present machine tools in operation or complex machinery displayed at trade exhibitions and agricultural fairs.

Photographers’ self-reflection and projection

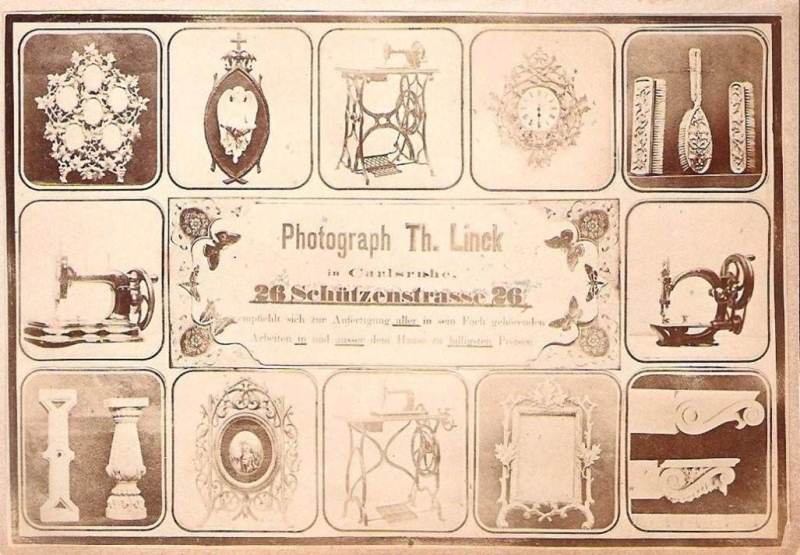

The photographic industry professionalized during the nineteenth century to meet – and sometimes to create – the demand for advertising. The first recognizable advertising agencies in the field were what were called ‘space jobbers’, such as Edward Trust, operating out of Philadelphia in the 1870s. The self-styled ‘originator and general manager’ of the United States Cabinet Photo-Advertising Company published and disseminated stock images carrying advertising matter from multiple customers in a single locality. He used the same method for a different format under the appellation U.S. Stereo View Advertising Co. This was a similar technique to that employed by Cummings’ Patents in Edinburgh, Scotland, in the 1890s but was not current in the Low Countries before the First World War. It was more common in Europe for individual professional photographers to set themselves up as specialists in advertising. How widespread this practice was can be gauged from this carte by Thomas Linck soliciting custom from regional Karlsruhe in Germany, a town of scarcely 80,000 inhabitants in 1890 (fig. 25).

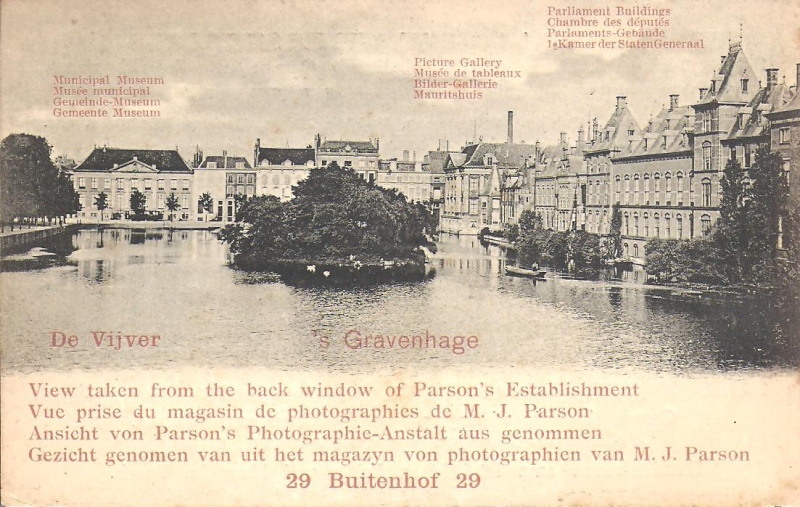

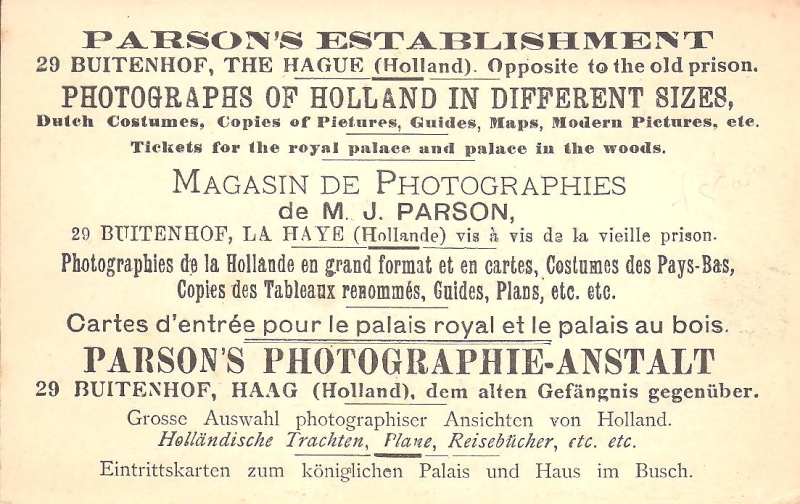

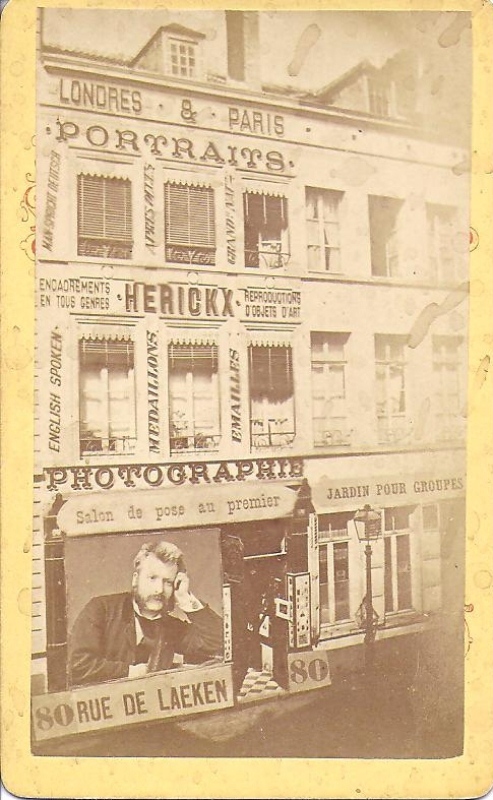

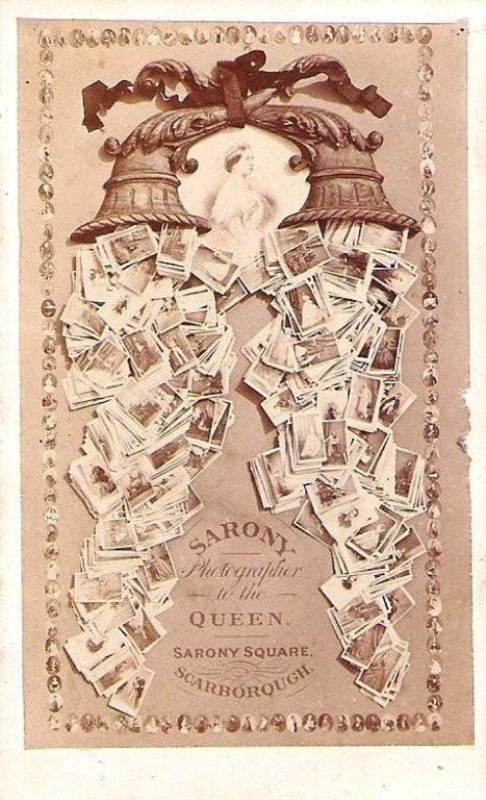

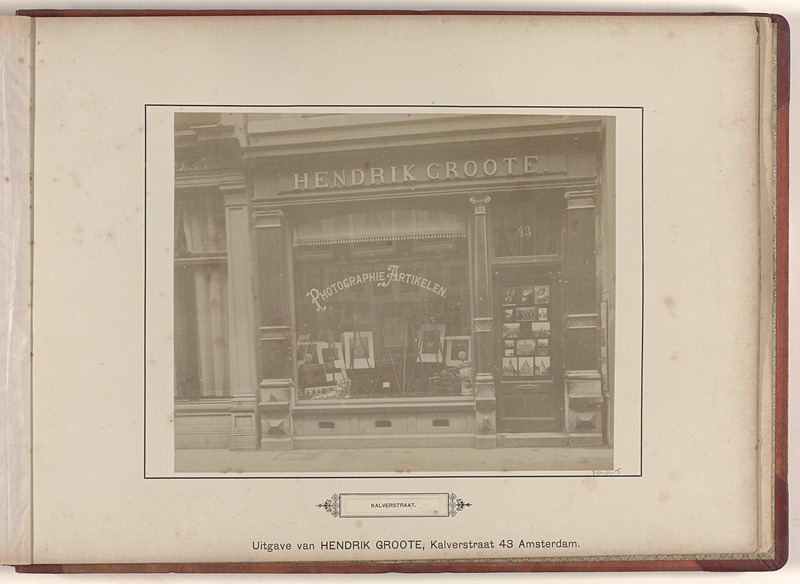

Around the turn of the century, when the standard transmission format of the cabinet card had transmuted into the postcard so as to travel more lightly, a whole sub-industry of suppliers sprung up (fig. 26a). For every sober and factual sales pitch, like this one by Parsons in The Hague (fig. 26b), there were others communicating in a visual style both more creative and equally suited to the requirements of marketing. In fact, photographers were often at their most imaginative when advertising their own products and services. Freed from the constraints of having to please paying clients, they could give free rein to their imagination. Where photographers’ self-advertising excelled was in the skillful use of composite imagery and collage. Elaborate compositions demonstrated the range of a studio’s output or indicated the studio address in ludic style (fig. 27). Alternatively, a photographer could project imagery as metaphor: the portraitist Sarony creates a cornucopia of cartes, releasing a shower of portraits, with Queen Victoria at the social apex of the English society he depicted (fig. 28). In contrast, those photographers wishing to project sobriety could always fall back on the trope of a shop window presenting a range of goods for sale (fig. 29).

Conclusions

The period surveyed by this article ends around 1920. The spirit of modernism, not as antithetical to commercial considerations as the previously paramount Pictorialist movement, embraced advertising photography in ways to formulate a new aesthetic. Whereas dramatic lighting, clever retouching, combination printing, complex staging, even soft focus, were shared techniques long before twentieth century advertising photography appropriated them, the market embraced them as never before in the decade following the First World War. American historiography has adopted the year 1922 as ushering in the new era of photographic advertising on the basis of statistical importance and professional organization; that year saw an exclusively photographic exhibition organized by the Art Directors Club of New York.[16] After the trauma of the First World War and the ensuing Depression, Europe had a lower penetration of photographic advertising than the United States. Furthermore, the persistence of local and artisanal-based economic structures probably held back the branding and mass marketing that underpinned much of photographic advertising from now on. Nevertheless, advertising photography reached a critical mass in the Low Counties during the 1920s, typified by Piet Zwart’s impressive series and beautifully designed catalogue for the Nederlandsche Kabel Fabriek in 1927-28.[17]

In retrospect, this article has attempted to demonstrate the broad and eclectic reach of early photographic advertising, when a fledgling technology began its long transformation into a powerful tool for industry and commerce. Literalness and interpretation could go hand-in-hand, as the pioneers created a new visual vocabulary and paved the way for the advent of mass marketing at the dawn of the twentieth century.

There is much we do not yet know about the first eighty years of photographic advertising, the scope of individual campaigns, the number and calibre of photographers active in the field, the reception and impact of photographic advertisements. What I have tried to establish is that it was a relevant and vibrant field, worthy of judgment on its own terms and not through the lens of twentieth century orthodoxy. Gerry Badger summed up why the old assumptions about taxonomy and genre no longer hold: ‘The parallels between the 19th century and today go beyond staging and manipulation. Then photography was too new to be confined by definitions of what it could or couldn’t be. It was anything that photographers wanted it to be, from high art to low commerce. In the 20th century, definitions and distinctions grew up, confining photography’s erratic genius into tightly controlled channels. In the 21st century, the rigid division of photography into categories like fashion, advertising, art or documentary, have collapsed. Once again, photography is anything that photography wants to be.’[18] Early advertising photography, the historiographic enigma and a long neglected corner of our visual heritage, is now ripe for re-assessment.

CV

Steven F. Joseph is an independent scholar, based in Brussels and Paris. He researches and publishes on the subject of early photography in Belgium, and on photography applied to book illustration in the nineteenth century. He is currently building up a database of primary and secondary materials documenting the emergence of photography in advertising on a world-wide basis before 1914. Steven Joseph is a member of the editorial board of Depth of Field.↑

Notes

1. Burney 1776, p. 11.↑

2. Sobieszek 1988, chapter ‘Beginnings 1865-1921’, pp. 16-29, includes 6 figures and 9 plates.↑

3. Sobieszek 1988, p. 16.↑

4. Lorelle and Langelaan 1949, p. 6.↑

5. Catalogue de la quatrième exposition de la Société française de photographie, Paris 1861, p. 13, entries 307-8.↑

6. Rickards, Maurice, Collecting Printed Ephemera, Oxford 1988, p. 7.↑

7. http://www.bl.uk/onlinegallery/onlineex/evancoll/ (accessed November 2012)↑

8. http://www.bl.uk/catalogues/evanion/Record.aspx?EvanID=024-000000336&ImageIndex=0 (accessed 29 November 2012)↑

9. ‘Miscellaneous. Photography as an Advertising Medium’, The Photographic News, vol. 2, 18 March 1859, p. 22.↑

10. Patent Office, Patents for inventions : abridgements of specifications. Class 3, advertising and displaying, 1855-1866, London 1903 et ff.↑

12. ‘Imprimerie photographique de Radoux’, Uylenspiegel, vol. 2, 7 June 1857, p. 8.↑

13. Advertisement appearing of the front inner cover of individual issues of Street Life in London, London 1877-1878, preserved with original fascicle wrappers intact in Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam, call number F 351 C 9.↑

14. Adams 1904, p. 130.↑

15. Sampson 1874, p. 556.↑

16. Sobieszek 1988, pp. 30-1.↑

17. http://www.nederlandsfotomuseum.nl/component/option,com_nfm_collection/sub,result/method,theme/Itemid,153/id,1013/lang,nl/ (accessed on 29 November 2012) ↑

18. Badger 2007, p. 200.↑

References

Joseph H. Adams 1904, ‘Photography in Advertising’, The Photo-Miniature, n° 63, June, pp. 129-171.

Gerry Badger 2007, The Genius of Photography: how photography has changed our lives, London.

Charles Burney 1776 (reprinted 2010), A General History of Music, London, vol. 1.

Margaret Denny 2008, ‘Advertising Uses of Photography’, in: John Hannavy (ed.), Encyclopedia of Nineteenth-Century Photography, New York/London, vol. 1, pp. 9-12.

Colin Harding 2005, ‘Advertising of Photographic Products’, in: Robin Lenman (ed.), The Oxford Companion to the Photograph, Oxford/New York, pp. 4-5.

Heinz K. Henisch 1994, and Bridget A. Henisch, ‘Advertising and Publicity’, in: The Photographic Experience 1839-1914. Images and Attitudes. University Park, PA, pp. 228-65.

Patricia Johnston 2005, ‘Advertising Photography’, in: Robin Lenman (ed.), The Oxford Companion to the Photograph, Oxford/New York, pp. 5-7.

Lucien Lorelle and Donald Langelaan 1949, La Photographie publicitaire, Paris.

Elizabeth Anne McCauley 1994, Industrial Madness. Commercial Photography in Paris, 1848-1871, New Haven/London.

Michael Pritchard 2008, ‘Advertising of Photographic Products’, in: John Hannavy (ed.), Encyclopedia of Nineteenth-Century Photography, New York/London, vol. 1, pp. 8-9.

Rev. W.J. Read 1856, ‘On the Applications of Photography’, Photographic Notes, vol. 1, 15 October, pp. 201-4.

Henry Sampson 1874, A History of Advertising from the Earliest Times, London.

Robert A. Sobieszek 1988, The Art of Persuasion: A History of Advertising Photography, New York.

Erich Stenger 1938, ‘Werbephotographie’, in: Die Photographie in Kultur und Wirtschaft, Leipzig (reprint 1992), pp. 97-8.