Archival, Vernacular and Multi-reproduced Images: Photography in the Work of Jef Geys

Abstract

From his debut in 1958 onwards, Belgian artist Jef Geys (b. 1939) worked with photography. This makes him an absolute pioneer within the Belgian art world—immediately followed by Jacques Charlier and Marcel Broodthaers, who from their debut in the early 1960s also made photo-based art. Throughout Geys’s multimedia practice photography takes a prominent place: not only in the number of works that involve photographs but also in the establishment of his archive, which is a fundamental component of his work. In addition, what makes Jef Geys an interesting case is that his idiosyncratic oeuvre spans the whole period in which photography became an autonomous medium within the domain of contemporary art in Belgium—a state that was finally achieved in the early 1990s. This article provides a first selective overview of Geys’s photo-based work and shows how his specific use of the medium corresponds with the basic principles on which his oeuvre is built.

From his debut in 1958 onwards, Belgian artist Jef Geys (b. 1934) worked with photography. This makes him an absolute pioneer within the Belgian art world – immediately followed by Jacques Charlier and Marcel Broodthaers, who from their debut in the early 1960s also made photo-based art.[1] Through their particular use of photography, among other media, their work of the 1960s and 1970s aligned with the international contemporary artistic movement of Conceptual art. During the past decade, several scholars writing on photography have argued that the use and presentation of photography within Conceptual art has been vital in the process of photography entering the domain of the visual arts. Similar conclusions are found in writings by David Campany, Douglas Fogle, T. J. Demos, Diarmuid Costello and Margaret Iversen, and Hilde Van Gelder and Helen Westgeest.[2] In-depth investigation into/of the use of photography by Belgian artists shows that also in Belgium the artistic ‘emancipation’ of photography starts with Conceptual art practices, like those of Geys, Charlier and Broodthaers.[3]

Throughout Geys’s multimedia practice photography takes a prominent place: not only in the number of works that involve photographs but also in the establishment of his archive, which is a fundamental component of his work. In addition, what makes Jef Geys an interesting case is that his idiosyncratic oeuvre spans the whole period in which photography became an autonomous medium within the domain of contemporary art in Belgium – a state that was finally achieved in the early 1990s, when, for example, the work of documentary photographer Carl De Keyzer had entered the Museum of Contemporary Art in Ghent. Converging with the Belgian history of photography’s artistic ‘emancipation process,’ his oeuvre starts with a conceptual use of photography and later develops into a more pictorial, large-scale application of the medium that would become the dominant model in the 1980s and 1990s. Moreover, Geys’s engagement with the vernacular and his primary and continuous attempt to reconcile art and everyday life are general characteristics of the photo-based work made by Belgian artists within this period and might be drawn back to the strong local tradition of Surrealism. For, certainly the Brussels Surrealist group led by Paul Nougé and René Magritte intended to create connections between art and real life.[4] This article provides a first selective overview of Geys’s photo-based work and shows how his specific use of the medium corresponds with the basic principles on which his oeuvre is built.

Geys’s Archival Practice

The book entitled, Jef Geys. Al de zwart-wit foto’s tot 1998 (Jef Geys: All the Black-and-White Photographs until 1998) demonstrates the prominent position the medium photography occupies within Jef Geys’s oeuvre. In 1998, Geys published this five-centimetre thick book that contains 500 pages of photographs that are reproduced in a random order in the form of contact prints. According to the artist, he made roughly 40,000 photographs between approximately 1958 (from his time at the Academy) and 1998.[5] Between pages 1 and 500, a wide range of subjects are presented, including family members, friends, animals (horses, cows, cats, dogs), a bodybuilder, ‘classical’ as well as pornographic nudes, old (family) pictures, magazine covers, students, flowers, wood-paths, seed-bags, castles, churches, farms, row houses, domestic, museum and class interiors (fig. 1), buildings under construction, shadows of architectural elements or human figures, election posters, art works made by Geys as well as by other artists, catalogues and magazines in which his work is published, musicians playing a concert, cars, record covers, close-ups of body parts, a harbour, kermis races, trucks and television screens.

This publication was conceived as an artist’s book: apart from the title, there is neither text explaining the aim of the book nor interpretations of the pictures. Also lacking are the captions, customary in photobooks. In the end, it simply forms a huge collection of miscellaneous photographs that have an amateurish look; the photos are often over-exposed or under-exposed, and the subjects are often extremely banal. The photographs, taken all together, could be considered as one (still ongoing) inventory of the artist’s life. Four years after the publication of Jef Geys. Al de zwart-wit foto’s tot 1998, Geys presented the film Dag en Nacht en Dag en… (Day and Night and Day and…) at Documenta 11 in Kassel. The ‘film’ includes a 36 hours projection of a compilation of thousands of photographs from his archive. As retrospective works the book and the film show in general terms what photography does, what photography is: a means to inventory (one’s life), to grasp the now and to preserve, to record, to collect, to document (the past; everything he can or wants, seemingly without selection). At the same time it illustrates the importance of photography – the ultimate medium to represent the vernacular (banal or sentimental subjects; ordinary people and their ordinary habits and activities) as well as the ultimate vernacular medium (the medium of the amateur picture maker) – in Geys’s artistic practice, which concentrates on the connection between art and everyday life. The vernacular quality of photography actually goes to the heart of Geys’s oeuvre.

Geys’s archival practice is evident not only in his gigantic photo archive but also in his inventory of all the works he has created since his debut in 1958. The inventory, arranged chronologically, lists of the following information for each work: ‘subject’ (the title of the work), ‘nature’ (the material(s), plus sometimes the dimensions of the work), ‘year’ and ‘number’ (the number of copies, varying from 1 to ‘unlimited’). Geys’s inventory was published, for example, in the catalogue of the group exhibition Aktuele Kunst in België, Inzicht/Overzicht, Overzicht/Inzicht (Museum voor Hedendaagse Kunst, Ghent, 1979). The inventory replaced the classical short bio of the artist at the end of the catalogue and shows how many works up to 1979 Geys had realized entirely or partly by means of the photographic medium. In no less than seventy-five of the 180 works in the list, photography – and photocopy, which Geys also considers as a form of photography – is mentioned as a material used, next to other materials including painting, drawing, fibreboard, wood, steal, stickers, fabric, and paste.[6] Special emphasis is laid on the period 1966 to 1972 – a time frame that contains sixty-five photographic works. Geys, therefore, is one of the first artists in Belgium who intensively used photography.

In conjunction with the inventory, Geys created a true ‘documentation centre’ in which he files all kinds of information in the form of press cuttings, pictures, notes, letters, documents, books, catalogues and videos. These files function as ‘raw material’ on which he had already based an artwork or in which he could draw from in the future to initiate a work of art. Items from the archive are thus used and reused to create new works. Through his exploitation of the archival function of photography since the 1960s, Geys’s practice aligns with that of other, more internationally known artists of his generation, such as Robert Smithson, Hans Haacke, Gerhard Richter, Bernd and Hilla Becher, and the Belgian Marcel Broodthaers.

Since 1969, the so-called Kempens Informatieblad – a regional newspaper taken over by the artist – has accompanied every one of Geys’s exhibitions. To the present day, the use of the Kempens Informatieblad is a substitute for an exhibition catalogue and is offered (almost) for free – it serves as a reaction against the undemocratic prices of art books.[7] Each issue of the Kempens Informatieblad includes various data (often photographs) drawn from his archive, which give the visitor supplementary information about the exhibited works of art and their origins. Since the Kempens Informatieblad is directly related to the exhibition for which it was conceived, but does not necessarily includes the exhibited works, it can also be considered as an important element within the exhibition.[8] The conception of a catalogue that functions as the exhibition evokes the pioneering initiatives of the New York curator and art dealer Seth Siegelaub. Famous examples are the Xeroxbook from 1968, which was an exhibition in the form of a book, and January 5-31, 1969, the 1969 group exhibition of the work of Robert Barry, Douglas Huebler, Joseph Kosuth and Lawrence Weiner in which ‘the exhibition was the guide to the catalog’ and not the other way around.[9]

Geys’s didactic sensitivity, which the Kempens Informatieblad demonstrates, followed from his daily activity as a teacher of visual arts at a primary school in Balen, a job he practiced from 1960 until 1989. This professional activity intertwined completely with his activities as an artist. Through his connections with the art world, for example, he was able to bring real art works from the collection of the museum of contemporary art in Ghent into the classroom. Conversely, pictures of his pupils, for instance, formed the basic material for his work Lapin Rose Robe Bleu (see below). The close connection between Geys’s teaching, his documentation centre, his artistic oeuvre and the Kempens Informatieblad is crucial to understand his artistic practice, for these elements indicate the close relationship he wanted to establish between art and everyday reality. Through his multifaceted activities – as a ‘multimedia artist’ and as a teacher – he attempted to blur the boundaries between the social, the political and the aesthetic. He essentially wanted – and still wants – the difference between high and low art to be indistinct.[10] And, as the following examples will show, the medium of photography proves to be an ideal ‘conductor’ to realize this.

The First Photo-based Works

The involvement of photography in Geys’s works began toward the end of the 1950s and the beginning of the 1960s.[11] Inventory numbers 2, 3, 4, 5 and 6, dating from 1958-1962, mention ‘photo + story on tape.’ This combination of materials is also found in inventory numbers 29, 30, 31, 33, 34 and 35, which report ‘tape, drawing + photo.’ The photographs in the earliest works are pictures from his youth, to which he added a story, recorded on tape. According to the artist, the story tells his (traumatic) memory related to what is seen in the picture.[12] These very early works involve already the main features of Geys’s oeuvre: the blurring between his private life and his activities as an artist, the use of archival material such as family pictures, and the combination of different media, including photography and text, which are in relation to each other.

The mingling of life and art and of artistic media – as seen in the first works – is also present in one of the artist’s best known projects, entitled Seed-bags. Every year since 1963 to the present, Geys artistically renders a seed-bag of flowers or vegetables. He realizes them on two formats – a small format (ca. 18 x 24 cm) on canvas and a larger format (90 x 135 cm) with enamel paint on panel – and presents them with the Dutch and Latin names of the plant and the year the painting was made.[13] He started this project because of the frustration he felt when he realized that the picture of the flowers or vegetables pictured on the cover of the bag did not resemble the plants that had grown from the seeds of the bag; there was a disconnection between the represented and the real.[14] The hyperrealist paintings, based on photographs, allude to the gap between reality and representation. Here, Geys aimed to expose the ‘make-believe world,’ with which photography always has been involved.[15]

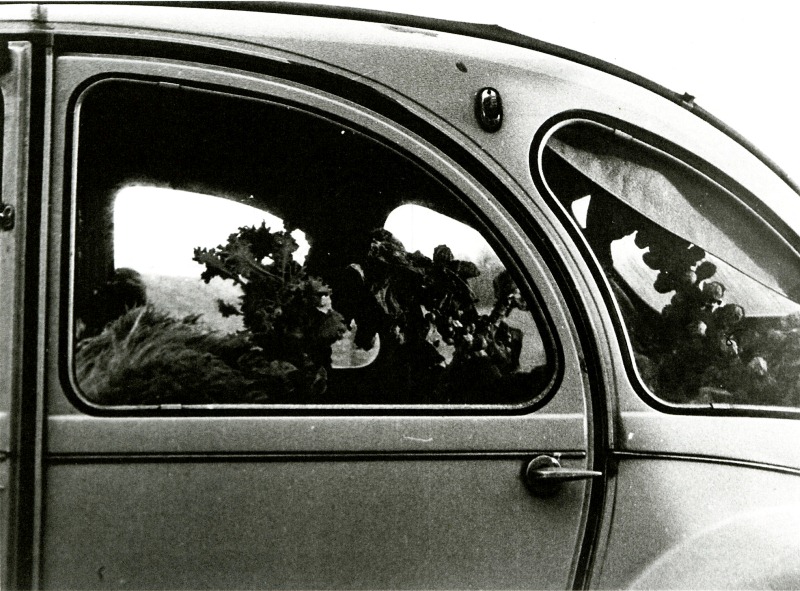

Geys’s interest in the relationship between nature and the human being also comes to the fore in other works. Around 1967, he wanted to capture the entire process from ploughing the ground and sowing, to fertilizing and harvesting. In an interview conducted by Herman De Coninck for the magazine Humo, Geys explained his intentions as follows: ‘I thought [that] it should be finished with Minimal art and that only one thing of sense was left: to work in your garden, to turn over the ground, to cultivate your own cabbages without DDT and so on: that is important.’[16] He thus started to experiment in his garden and documented it – by means of photography – as an artistic project. During the whole process, he added ‘sentimental acts’ in order to connect the artistic/natural with a human element. For instance, he wept as he burnt old letters and memories from his youth and then used the ashes as fertilizer.[17] With the products he harvested, he made his so-called ‘edible art.’ With the corn, for example, he baked bread in the form of a heart. The breads, together with home-grown cabbages and sprouts, were ‘exhibited’ in 1968 in Galerie Kontakt in Antwerp. For the occasion, the gallery was transformed into a shop that offered Geys’s edible art for sale.[18] After the exhibition, Geys placed the sprouts in the backseat of his Citroën 2CV ‘with the intention of letting them see the “hinterland”’ during a driving trip through Belgium (Fig. 2).[19] After the ‘tour,’ he planted them in an open landscape and then watched the reactions of the people living in the neighbourhood. For example, most of the people came to collect the cabbages that had been grown in the ground, but left the ones that had been grown in a refuse dump.[20] Shortly thereafter, on the occasion of a sculpture exhibition organized by Karel Geirlandt, Geys planted cabbages in the Ghent Zuid Park.[21]

|

Fig. 2. Jef Geys, Cabbages in car, c. 1968. Black-and-white photograph, published in e.g. Kempens Informatieblad, Speciale Editie Biennale Venetië, 2009, p. 11. © Jef Geys |

During the making of this work photography played a rather secondary role: as a means to merely document each step of the project. Through the photographs, however, the work could enter his archive and, as such, his oeuvre. In addition, when Geys showed the pictures later in exhibitions and recorded them in his Kempens Informatieblad, it is clear that he considered the photographs of the project to be art. Photography increasingly proved to be the suitable medium for Geys to realize work that is related to daily life and his immediate surroundings.

The Vernacular

The first major work in which photography played a prominent role from the start, is a work about a young cyclist, created in 1968-1969. It consists of a sequence of framed documents (typed letters, cuttings and an address book) and black-and-white photographs that were glued onto fibreboard and cardboard (Fig. 3). The story goes as follows: War Jonckers, a bartender at ‘Bar 900’ and a friend of Geys, had a 15-year-old son, Roger, who appeared to be good at cycling. It was also during this same time that the famous cyclist, Eddy Merckx, was a rising star and served as an example for many young Belgian boys such as Roger. Geys became the guardian of Roger and coached him by his partaking in kermis races. In return, he asked Roger to describe his experiences that Geys would write down. Geys then sent these descriptions to certain people he knew in the art world who were listed in the address book included in the work. During the summer, Geys travelled to the south of France to follow Merckx in the Tour de France. He then reported back to Roger by means of letters and photographs about Merckx’s cycling techniques and day-to-day living habits. Strikingly, Geys began his letters to Roger with the salutation ‘Dear Jef,’ as if it had been Roger who wrote the letters to him.[22] The identities of Geys and the boy gradually intermingled. According to Geys, the aim of the project was ‘to come as close as possible to the boy, trying to capture the phenomenon as accurate and complete as possible.’[23] Therefore, he carefully wrote down his and the boy’s experiences. ‘I was not interested in the background, the corruption within cycling,’ he said, ‘I was interested in what happens with the little one, where it all begins, how and when you could proceed to shoot, for, at a certain moment, we all shoot, so to speak.’[24] In the 1971 interview conducted by Flor Bex, Geys said: ‘I wanted to examine what was going on in the mind of that boy, what the influences from his family circle meant, etc. So, day after day I followed him. Every Sunday we drove to a race. I regularly sent messages about the boy to a number of randomly chosen addresses. The aim was to fully infiltrate myself into a situation in order to understand it and then communicate about the whole purpose to an audience.’[25]

In one of the documents of the work, Roger (alias Geys) indeed introduces himself, talks about cycling and promises the reader he will report about his performances. The content of the letter also implies the great expectations regarding Roger’s career as a cyclist, especially by his father. In addition, Roger’s membership card of the Belgian cycling federation is shown, next to a whole set of reportage photographs in which we see the following images: the boy training in the kitchen (Fig. 4); the father and his friends at a cycling race; a discussion of cycling strategies at the kitchen table; a mayor speaking to the riders at the start of a race; the Mercedes of the boy’s father; the boy taking his bike; and Geys massaging him. As a sort of grand finale, a photo in poster format is added, which was taken by Geys at the Vélodrome de Vincennes at the moment that Eddy Merckx won the Tour de France in 1969; yet, neither the famous Belgian cyclist, nor any other cyclists are seen in the picture. The backs of three cycling fans actually obstruct the view of the winning moment. The viewer then realizes that the boy is also never actually depicted in the other photographs as a participant in a race. Moreover, the press cuttings reveal that Roger never won a race but always ended as one of the latest. The cycling adventure of Roger Jonckers, who had to deal with a lot of pressure, particularly by his father, seems to have ended in a failure. By means of photographs and written documents, Geys ultimately offered an account of a young man who was talked into starting a career as an amateur cyclist, which ended in a personal fiasco.[26]

The cyclist work shows Geys’s distinct interest in the human condition and illustrates once more his particular attention to the relation between art and everyday life. He carefully approached his subject with a sense of philanthropy and irony at the same time. He elevated the common and gave value to the banal by bringing it into the museum; the common world and the art world intermingled. In this work the notion of the vernacular – as regards subject matter (the popular realm of amateur cycling) as well as the execution of the work in rather ‘poor’ materials – is clearly present. Therefore, the work completely aligns with what Jeff Wall called the ‘amateurization’ within conceptual photography.[27] In addition, the work can be interpreted as a parody of photojournalism – another characteristic of photoconceptualism as described by Wall.[28] Geys used the classical elements of photojournalism – photographs and text – for a topic – cycle racing – that certainly in Belgium is a common subject in the papers. At the same time, however, he parodied the genre by introducing vernacular elements, such as amateurish, ‘bad’ photographs in which the subject is often obscured, and highly subjective texts, such as letters in which he also plays with authorship. Just like other conceptual artists, including Robert Smithson (the example Wall gives), Geys adopts this strategy to raise social issues – in this case, the pressure that is exerted on young people and the social being in general to come up to parental/societal expectations.

A Photographic Retrospective at the KMKSA

Proceeding from his preoccupation with the connection of art and everyday life, Jef Geys always had an ambiguous relationship towards the art institute. A striking example of this is his proposal to blow up the Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten in Antwerp (KMSKA) at the end of his solo exhibition held there in 1971. In a letter to the Minister of Culture from November 1970, which was published later in the catalog Ooidonk 78, Geys described his plans about the explosion of the KMSKA as follows: ‘Departing from the idea that every society, authority, institution, organization, person, etc. includes the seeds of its own destruction, the first and most important task of every society, authority, etc. in my opinion is to recognize, isolate and neutralize these seeds. The most efficient way to achieve all this then seems to me to systematically, scientifically and deliberately set about the problem. […] So I would like to start a project, which, if executed, would result in the destruction of the Museum voor Schone Kunsten.’[29] Furthermore, he asked for the Minister of Culture’s cooperation to get the approval of the management and staff of the KMSKA as well as the participation of the fire brigade, the Engineering Corps and the Poudreries Réunies (a gunpowder factory) of Balen.

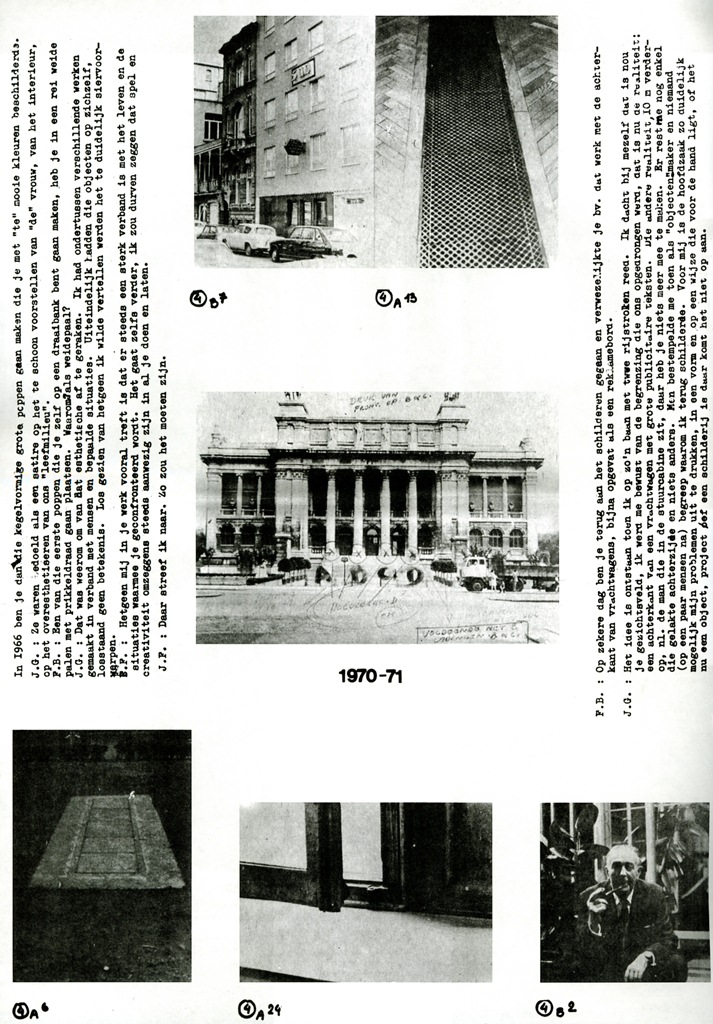

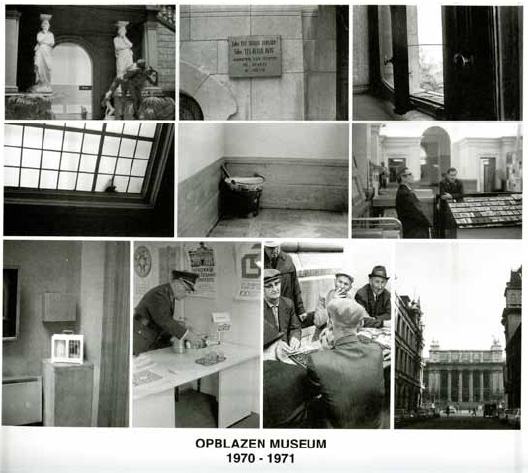

Of course, Geys’s request was not granted. Instead, the museum decided to send four hundred and fifty letters to Belgian artists asking their opinion about the project; their reactions would then be displayed in Geys’s exhibition.[30] In the museum galleries, Geys exhibited a selection of items from his archive, including pictures from his youth and a number of documents about the recent miners’ strike at Vieille Montagne in Balen.[31] In fact, the show was a photo exhibition, since Geys exclusively showed his work by means of photographic documents (Fig. 5). According to Geys ‘although [he] then had been making art for about twelve years, [he] did not feel it to be the right moment to show finished products, but [he] did want to show images of the works he had made so far.’[32] Through this decision of only displaying reproductions of his works instead of real works, Geys distracted the viewer’s attention from the original, and – according to Walter Benjamin’s argument – stripped the works from their aura.[33] As will be explored later in this text, the reproducibility of photography will be one of the main reasons for Geys to use the medium. Next to the photographs that represent earlier works, the exhibition also included interior shots of the museum, which were made during the preparation of his plan to blow up the museum, and showed details of the glass roof, buckets with sand for fire safety, and other ‘weak spots’ of the museum infrastructure (cf. Fig. 1).[34]

|

Fig. 6. Jef Geys, Opblazen Museum 1970-1971, some pictures of the 1970 project, republished by Galerie Micheline Szwajcer in 2004. © Jef Geys |

Geys also focused on the human figure in that environment. For instance, there were pictures of attendants chatting at a sales stand with postcards, and an image of the security officer of the ICC who was permitted to uncork a champagne bottle at 4 pm every day and serve it to the visitors of the museum (Fig. 5– 6).[35] In the accompanying Kempens Informatieblad, a list of all the exhibited works, illustrated by photographs, was included, next to the text of an interview with the artist conducted by Flor Bex (Fig. 7). In this interview, Geys described his exhibition as a ‘manifestation,’ and explained that he continuously supplemented the exhibition with new works, in order to demonstrate that he did not consider the museum, art and reality as three separate, static domains.[36]

There is something paradoxical about the fact that Geys exhibited his works in the museum that he had earlier proposed to blow up. Geys argued that protest could only be concretized from inside the system.[37] In the end, the artist remarked that his proposal was taken too literally. In the conversation with Bex in 1971, he stated: ‘People cling to the word “blow up.” That is wrong. It is an attack on the structures, on the fact that, for example, the budget for culture of 1970 has only been voted now, that the Belgian museums have been in a sacred isolation for such a long time, that organizing exhibitions still is a system within a system, etc. Denouncing all of this is “blowing up the museum,” I felt the necessity to put my finger on the sore spot, on these obsolete structures, on the wretchedness of the current state and the entire socio-cultural order. […] To me it was a reaction to everything that was thwarting me in the present society and keeping me from what I actually wanted to be.’[38]

Geys’s perception of the museum and the way in which he makes that visible within his work, shows an affinity to the work of Broodthaers, who installed his Musée d’Art Moderne: Département des Aigles in the wake of May 1968 and the subsequent occupation of the Palais des Beaux-Arts in Brussels. Both artists intended that their near-contemporary ‘manifestations’ – Broodthaers founded a fictive museum outside the official art institutions in 1968, while Geys proposed the explosion of the museum in 1970 – would create a better sociological structure of the museum as an institution. Both works originated in a time when Belgium lacked serious platforms for contemporary art. Unlike Broodthaers, however, Geys stated that his proposal to blow up the museum was a strictly personal reaction against the abuses in the museum world, which had nothing to do with the contestations from 1968.[39]

When asked about his relationship to Broodthaers, Geys responded that he is ‘a country-boy from Balen,’ and, by contrast, sees Broodthaers as ‘someone from the city, directed towards Paris.’[40] He added that, contrary to his own intentions, ‘Broodthaers’ Musée d’Art Moderne was purely meant as an artistic intervention.’[41] By this statement, Geys pointed to a fundamental difference that he sees between his approach and that of Broodthaers. According to him, Broodthaers exclusively circulated in the art world, whereas he tries to unify the art world and real life, to consider it as one world. In this way, his position is similar to that of Jacques Charlier, who also combined his artistic activities with a regular job (at the Service Technique Provincial in Liège), and also operated from the periphery – Liège in the 1960s was quite remote from the avant-garde scene.

Photography’s Reproducibility

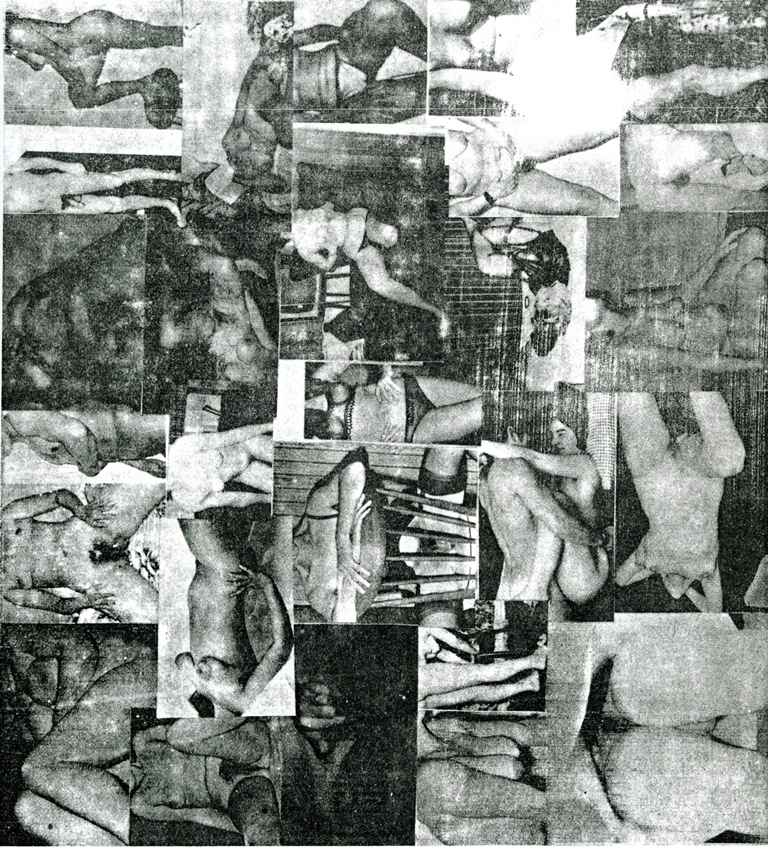

Only one year after causing a stir by proposing to explode the museum of Antwerp, Geys created another ‘museological’ sensation when the Van Abbemuseum in Eindhoven refused to exhibit his work entitled Juridisch aspect van emoties (Juridical Aspect of Emotions). Geys created the work for the exhibition Derde Triënnale der Zuidelijke Nederlanden in 1972. It consisted of two collages, the one with pornographic photos, the other with want ads from Dutch sex magazines. Through this material, Geys questioned the general supposition that in the Netherlands after the Provo movement ‘everything’ was accepted whereas in Belgium ‘nothing’ was allowed. The artist wanted to examine the emotional reactions and the limits of tolerance for both Dutchmen and Belgians, respectively, with regard to offensive images.[42] In the catalogue, Geys explained that the aim of the work was an awakening of the spectator to the shifting of societal norms, through which images were experienced and judged.[43] Jean Leering, director of Van Abbe, was forbidden to show Geys’s work by the mayor of Eindhoven, who argued that the project had more to do with psychology, sociology and sex than with art.[44]

|

Fig. 8. Jef Geys, Juridisch aspect van emoties (fragment), 1972. Print of collage of photographs, cut from magazines. © Jef Geys |

Another place to show the work was the Antwerp ICC – then one of the few forums for contemporary art in Belgium. Like Leering, ICC curator Flor Bex backed the project of Geys. Nevertheless, the Belgian policymaker also believed that showing the offensive material was problematic. In response, Geys decided to create a new version of the controversial photo collages. This new work consisted of seven prints of the same image (Fig. 8). The prints reflected the process of printing, in which the first prints show a clear, unambiguous image, while the last pints present an almost illegible, blank image. The last six prints were hung in reverse order, exposing the viewer to a series of increasingly legible images. The visitor then had to go to the info desk, at which point a signature was required by the viewer in order for him to obtain the seventh, most explicit image (for this purpose, Geys printed 300 copies). Next to the prints the ICC exhibition also included the correspondence and newspaper articles about the issues that surrounded the project in Eindhoven.[45]

Geys’s point of departure for the works for Van Abbe and ICC was not to smuggle pornography by any means into and out of the museum. The artist’s objective was to reveal the function of images in society and to explore the transformation of meaning in which images are subjected through time.[46] To achieve that aim, he wanted to elicit a reaction from as many people as possible about the meaning of the images on display at a given moment. Therefore, the images had to fulfil three conditions. First, they had to be able to evoke an emotional or at least powerful reaction from the viewer. Second, the photos needed a subject matter that was general enough to be meaningful for as many people as possible. Third, the images required a subject that was vulnerable to not only individual opinion but also to collective judgment.[47] To meet these requirements, Geys chose explicit images from porn magazines. This work shows once again Jef Geys’s distinct orientation towards vernacular (photographic) genres, in which he finds tools to affect the viewer. The work is an examination of the impact of photographic images; the medium used for this is vernacular photography; and the method to carry out the examination is photography’s reproducibility. For, it is through the multiple photographic reproduction that the viewer is exposed first to a fairly abstract, and therefore innocent (version of the) image, and eventually to a sharp, detailed, and therefore offensive (version of the) image.

|

Fig. 9. Jef Geys, Geel, rood, blauw enz…, 1979. Poster (930 x 620 mm), 20 photographs (180 x 240 mm each), 3 spotlights. Collection S.M.A.K. Ghent. © Jef Geys |

Another work in which Geys experimented with photography’s capacity to easily reproduce, is Geel, rood, blauw enz… (Yellow, Red, Blue etc…), created in 1979 (Fig. 9). It includes a large format poster with the portrait of a young woman and a baby. The work also involves twenty smaller pictures, presented in a frame. They are printed alternately in a more clear or vague way. The pictures that are the clearest represent the same mother-and-child portrait as in the poster; the others, that are printed more vaguely, show other images of women. The whole sequence is illuminated by three spotlights: one yellow, one red and one blue spot, referring to Barnett Newman’s famous Who’s Afraid of Red, Yellow and Blue?.[48] Geys deliberately used coloured light from spotlights instead of paint since a light projection is more fleeting than paint. The artist wanted to create an ‘anti-painting,’ in which the materials are less physically present than in a real painting such as Newman’s work.

In the catalogue of the Inzicht/Overzicht exhibition (1979), Geys wrote about the work: ‘The intention is to produce a work that has a purely aesthetical appearance with a symbolic content and which is in opposition to fashion. […] It is a story about death and being born. It is bullshit, presumptuous and literary. It is gradually freeing slyness out of a picture and replacing it in a series with a mother-in-law and a child. It is about women, children, mothers, daughters, girlfriends, friends and feelings.’[49] The large picture is in fact a found image, made by Douven—a ‘factory’, situated in Leopoldsburg, Geys’s hometown, which from right after World War II until the 1970s mass-produced oil paintings next to framed photographs and reproductions.[50] To the world-wide distributed image Geys added photographs, made by himself. Pictures of women he knew (his mother, girlfriends) alternate with further reproductions of the poster image and thus become equally universal.

Geys again played with the affective impact of one of the archetypes of vernacular photography: the picture of a mother with her baby. He explained in an interview that the pictures represent ‘emotional traps.’[51] According to the artist, the biggest ‘trap’ into which you can fall, is the mother and child. This is the reason why this motif is printed clearly and presented in a larger format than the other images in Geel, rood, blauw enz….

Although Geys wanted to create an ‘anti-painting,’ through the classic theme of mother and child, the use of frames, hung on the wall at eye level, and the red, yellow and blue spots, the installation holds pictorial references. This moves the work away from the conceptual art of the 1970s and orients it toward the art of the 1980s that has more theatrical, sometimes kitschy characteristics and in which the photographic tableau form breaks through.

|

Fig. 10. Jef Geys, Lapin Rose Robe Bleu, 1987. Prints of collage of photographs. Collection FRAC Nord-Pas de Calais. © Jef Geys |

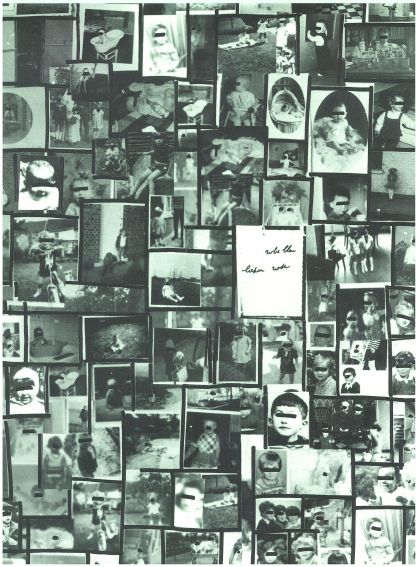

Unlike many artists who worked with photography in the 1960s and 1970s, Geys, in the 1980s, would not exchange his photographic practice for an exclusive focus on painting or sculpture but continued to use photography within his multimedia art. One example is the work, Lapin Rose Robe Bleu (1987; Fig. 10). The work was shown for the first time at the exhibition, Leo Copers, Thierry De Cordier, Jef Geys, Bernd Lohaus, Danny Matthys, Philip Van Isacker, Marthe Wéry at ELAC in Lyon in 1988. It consists of collages of black-and-white pictures of children that are printed on several sheets of paper. The sheets of paper are glued to the wall like wallpaper. The pictures are baby portraits of Geys’s former students, which Geys had kept in a box. On the back of the photographs he had written the name of the person in the picture. One of the photographs, however, did not bear a name but instead showed the inscription ‘lapin rose robe bleu [sic].’ A photographer, who had to colour the black-and-white picture, must have written the indicative inscription as a mnemonic.[52]

Jef Geys censored the photographs by crossing out the eyes of the portrayed children with a permanent marker. Consequently, the children are unrecognizable and without identity. Moreover, the monumentality of the wall, covered by countless small pictures, enhances the effect of anonymity. When the artist sold the work to Frac Nord-Pas de Calais, he did so on condition that when the work was to be shown somewhere, at least twenty pictures of local children had to be sent to the artist, who would make a collage of it, make the portrayed children unrecognizable, and then provide Frac Nord-Pas de Calais with additional prints including these new pictures. Through this method, Geys connects his artwork, which originated from pictures of his own environment, with the environment of the place where it is exhibited, and as such he creates a link between the art world and the everyday reality.

In Juridisch aspect van emoties, Geel, rood, blauw, enz… and Lapin Rose Robe Bleu Geys examines the impact of images through photography’s reproducibility. Universal images – of sex, of a mother and her child, and of schoolchildren, respectively – are shown in a repetitive way, through which their impact seems to increase and reduce at the same time. On the one hand, repetition has an indoctrinating, strengthening effect, but on the other, it also weakens (the impact/content of) the image. Correspondent with what Walter Benjamin in his classical essays, ‘The Work of Art in the Age of its Technological Reproducibility’ (1936) and ‘Little History of Photography’ (1931), initiated on the topic of reproducibility versus notions such as originality, authenticity and aura, the use of photographic reproductions is also a method for Geys to avoid the creation of ‘auratic’ unique artworks – a strategy that fits within his attempt to clear away the distinction between the art world and everyday life.[53]

Conclusion

The analysis of Geys’s photo-based work shows that his use of photography is based on three main features of the medium: its function as archival material, its vernacular qualities, and its reproducibility. In some of the works one of these characteristics might be manifestly present – as is suggested by the three sections within this article – but in fact they are all intertwined in each of the works discussed. The collection of images in each work is drawn from the artist’s archive or forms a new ‘subarchive’ in his oeuvre; the archival use of photography almost implies the application of photographic reproductions; the notion of the vernacular is present on a technical level (through the use of ‘poor’ materials and amateur pictures) as well as on a thematic level (subjects such as the amateur cyclist, the museum attendant, porn, family pictures of mothers and children).

Geys’s work is clearly embedded in the local: local people are often his subjects, a local newspaper is the primary medium to communicate about his work, and for a long time the local language, Dutch, was the only language he used. This might be an explanation for the fact that only from the early 1990s Geys received definite international recognition. Nevertheless, through the notion of the vernacular, the archival use of photography and the concept of reproduction – which can all be understood as strategies to reconnect art with everyday reality – Geys aligns with the use of photography within the international (post-)conceptual art scene, with reference figures such as Ed Ruscha, Robert Smithson, John Baldessari and Douglas Huebler. Let this case study of a body of works that is created in the periphery of the art world thus be a meaningful addition to the canonical history of art.

CV

Liesbeth Decan is an art historian. In 2011 she defended her Ph.D., entitled Conceptual, Surrealist, Pictorial: Photo-based Art in Belgium (1960s-early 1990s), at the KU Leuven. Since 2003 she teaches about the history and theory of photography at LUCA School of Arts – Campus Sint-Lukas Brussels. ↑

Notes

1. For a discussion of the photo-based work of Jacques Charlier and Marcel Broodthaers, see: Decan [forthcoming in 2013]. This article, which examines the work of Jef Geys, is a supplementary case study to the latter, forthcoming publication, which addresses the general history of photography being used by Belgian artists from the 1960s until the early 1990s. ↑

2. Campany 2003, pp. 11-45; Fogle 2003, pp. 9-19; Demos 2006, pp. 6-10; Costello and Iversen 2010, pp. 1-11; Van Gelder and Westgeest 2011, pp. 14-63.↑

3. Decan [forthcoming in 2013].↑

4. For a discussion of the ongoing influence of Surrealism on photo-based art in Belgium between the early 1960s and early 1990s, see also: Decan [forthcoming in 2013].↑

5. The oldest pictures in the book date from the 1950s, as confirmed by the artist in an interview with the author (Balen, 15 February 2010). In a second interview, Jef Geys explained that the 6 x 6 inch contact prints date from that earliest period (Balen, 14 June 2010). ↑

6. Jef Geys considers the photocopy as a form of photography based on its capacity to make ‘images’ through the reproduction of texts or pictures. (Interview with Jef Geys, Balen, 15 February 2010.)↑

7. Interview with Jef Geys, Balen, 15 February 2010. As early as the early 1960s, before owning the Kempens Informatieblad, Geys published items in it. According to the artist’s testimony, he started to accompany his exhibitions with the Kempens Informatieblad from 1969 onwards. These early issues, however, are lost. The oldest, still existing, dates from 1971. (Interview with Jef Geys, Balen, 14 June 2010.)↑

8. Deblauwe 2003 ↑

9. Seth Siegelaub: Exhibitions, Catalogues, Books & Projects, Interviews, Articles & Reviews,’ Stichting Egress Foundation, http://egressfoundation.net/egress/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=64&Itemid=310 (Accessed on March 23, 2010). ↑

10. Brayer 1992, pp. 3-4. ↑

11. According to Geys’s inventory, the very first work even dates from 1947, when Geys was only 13 years old. However, the artist only made his actual artistic debut in 1958, at the age of 24. ↑

12. Interview with Jef Geys, Balen, 14 June 2010; Bex 1971, z.p.↑

13. From 2007 onwards Geys also created the large format paintings on canvas. ↑

15. Interview with Jef Geys, Balen, 15 February 2010.↑

16. De Coninck 1972, p. 30. The original quote reads: ‘[…] vond ik dat ‘t maar eens gedaan moest wezen met die hele minimal art, en dat er maar één zinnig ding overbleef: in je tuin gaan werken, de grond omspitten, eigen kolen kweken zonder DDT en zo: dát is belangrijk.’↑

21. Bex 1971: z.p; Geys 2009, p. 9. ↑

22. Interview with Jef Geys, Balen, 15 February 2010. Since 2000, the letters to Roger are kept in the collection of SMAK, Ghent. ↑

23. De Coninck 1972, p. 30. The original quote reads: ‘[…] ik tracht hem zo dicht mogelijk te benaderen, tracht de realiteit van dat fenomeen zo akkuraat en zo totaal mogelijk vast te leggen.’↑

24. Ibidem. The original quote reads: ‘Mij interesseren b.v. niet de achtergronden, de korruptie in de wielersport, mij interesseert wat er met die kleine gebeurt, waar ‘t allemaal begint, hoe en wanneer je tot spuiten zou kunnen komen, want op zeker ogenblik spuiten we allemaal bij wijze van spreken.’↑

25. Bex 1971, z.p. The original quote reads: ‘Ik heb willen nagaan wat er allemaal omging in het brein van die jongen, wat de invloeden van zijn familiekring betekenden enz. Dag na dag heb ik hem dus gevolgd. Elke zondag reden wij samen naar een koers. Aan een deel op goed geluk gekozen adressen zond ik regelmatig berichten over die jongen. Dit alles om ergens weer volledig in te dringen om het te kunnen begrijpen en daarna te kunnen mededelen aan de mensen: dat was het hele opzet.’↑

26. As a sequel to this work, Geys sent a box to the Biennial of Madrid in 1969, an art event in which the theme was sports for that year. In the box, the artist laid out a variety of forms in Dutch and Spanish with information about his cyclist, Roger. The box was placed next to two vessels, in which people could then deposit their opinion. The artist also expressed his wish that an inhabitant from Madrid would correspond regularly with his cyclist. These letters and photos would then be displayed on-site. However, the box was never opened and instead was sent back to the artist, its content having not been exhibited. Since then, the box is part of the installation. Bex 1971, z.p.; De Coninck 1972, p. 30; Braet 1989, p. 130.↑

29. Geys 1978 [1970], p. 101. The original quote reads: ‘Vertrekkend van de idee dat in elke maatschappij, instantie, instelling, ordening, person, enz. de kiem van eigen vernietiging aanwezig is, heeft m.i. elke maatschappij, instantie, enz. als eerste en belangrijkste taak deze kiem te onderkennen, te isoleren en te neutraliseren. Welnu, de meest efficiënte wijze om dit alles te verwezenlijken, lijk[t] mij het probleem planmatig, wetenschappelijk en met voorbedachten rade aan te vatten. […] Ik zou dus een project willen op touw zetten dat, indien het werd uitgevoerd, de vernietiging van het Museum voor Schone Kunsten voor gevolg zou hebben.’↑

31. Lambrecht 2004, p. 20; Pas 2005, p. 97. ↑

32. Interview with Jef Geys, Balen, 15 February 2010.↑

33. Benjamin 2008 [1936], pp. 19-55; Benjamin 2008 [1931], pp. 274-298.↑

34. Interview with Jef Geys, Balen, 15 February 2010.↑

35. Lambrecht 2004, p. 20.↑

36. Ibidem.↑

37. Bex 1971, z.p; Kaizer 1990, p. 456. ↑

38. Bex 1971, z.p. The original quote reads: ‘[…] de mensen klampen zich nu vast aan het woord “opblazen”. Dat mag niet. Het is een aanval op de strukturen [sic], op het feit dat bv. de begroting cultuur 1970 nu pas gestemd is, dat de Belgische musea al zo lang in een geheiligde afzondering blijven staan, dat het inrichten van tentoonstellingen nog steeds een systeem blijft in het systeem enz… Dit alles aan de kaak stellen is “het museum doen ontploffen”. Ik voelde de noodzaak de vinger op de wonde te leggen, op deze verouderde strukturen [sic], op het lamlendige van de huidige toestand en van gans het maatschappelijk-cultureel bestel. […] Voor mij was het een reactie op al hetgeen mij dwars zit in de huidige samenleving en mij belet te zijn wat ik eigenlijk wil zijn.’↑

39. Interview with Jef Geys, Balen, 14 June 2010. ↑

40. Interview with Jef Geys, Balen, 15 February 2010.↑

41. Ibidem.↑

42. Ibidem.↑

43. Derde Triënnale der Zuidelijke Nederlanden (1972), z.p. ↑

44. Pas 2005, p. 116. Also see this publication by Johan Pas for a more extensive account of the matter.↑

45. Ibidem. ↑

46. Interview with Jef Geys, Balen, 15 February 2010.↑

47. Letter written by Jef Geys, dated 13 October 1972, published on the occasion of Geys’s second exhibition in the Van Abbe Museum in 2005: Kempens Informatieblad, Speciale editie Eindhoven (2005). ↑

48. Interview with Jef Geys, Balen, 15 February 2010. ↑

49. Inzicht / Overzicht. Overzicht / Inzicht. Aktuele Kunst in België (1979), p. 61.↑

50. Wynants 2011, pp. 3-5. ↑

51. Interview with Jef Geys, Balen, 14 June 2010.↑

52. Ibidem.↑

53. Benjamin 2008 [1936], pp. 19-55; Benjamin 2008 [1931], pp. 274-298.↑

References

Walter Benjamin 2008, ‘The Work of Art in the Age of its Technological Reproducibility’ (1936), in: Michael W. Jennings, Brigid Doherty, and Thomas Y. Levin (eds.), The Work of Art in the Age of its Technological Reproducibility, and Other Writings on Media, Cambridge, Mass./London, pp. 19-55.

Walter Benjamin 2008, ‘Little History of Photography’ (1931), in: Michael W. Jennings, Brigid Doherty, and Thomas Y. Levin (eds.), The Work of Art in the Age of its Technological Reproducibility, and Other Writings on Media, Cambridge, Mass./London, pp. 274-298.

Florent Bex 1971, ‘Uit een vraaggesprek – Florent Bex – Jef Geys,’ Kempens Informatieblad. Speciale editie Balen, March 27, z.p.

Jan Braet 1989, ‘Het zaad van Balen,’ Knack, June 22, p. 130.

Marie-Ange Brayer 1992, ‘De kleine identiteiten,’ Jef Geys. Paleis voor Schone Kunsten Brussel. Palais des Beaux-Arts Bruxelles, Visie, vol. XI, Zedelgem, pp. 3-4.

David Campany 2003, ‘Survey,’ in: David Campany (ed.), Art and Photography, London-New York, pp. 11-45.

Diarmuid Costello and Margaret Iversen 2010, ‘Introduction: Photography After Conceptual Art,’ in: Diarmuid Costello and Margaret Iversen (eds), Photography After Conceptual Art, Malden-Oxford-Chichester, pp. 1-11.

Derde Triënnale der Zuidelijke Nederlanden, exh. cat., Eindhoven: Stedelijk Van Abbemuseum, 1972.

Dirk Deblauwe 2003, ‘Jef Geys. Vragen uit Balen,’ Rekto:Verso, 2, November-December. (http://www.rektoverso.be, accessed on October 6, 2011)

Liesbeth Decan [forthcoming in 2013], Conceptual, Surrealist, Pictorial: Photo-based Art in Belgium (1960s-early 1990s), Lieven Gevaert Series, Leuven.

De Coninck, Herman, ‘Humo sprak met Jef Geys,’ Humo, 1972, pp. 27-30.

T. J. Demos 2006, ‘The Ends of Photography,’ Vitamin Ph: New Perspectives in Photography, London-New York, pp. 6-10.

Douglas Fogle 2003, ‘The Last Picture Show,’ in: Douglas Fogle (ed.), The Last Picture Show: Artists Using Photography 1960-1982, exh. cat., Minneapolis: Walker Art Center – Los Angeles: UCLA Hammer Museum, pp. 9-19.

Jef Geys 1978, ‘Letter to the Minister of Dutch Culture’ (November 11, 1970), in: Ooidonk 78, exh. cat., 101.

Jef Geys 2009, Kempens Informatieblad. Speciale editie Biennale Venetië,.

Jef Geys 2005, Kempens Informatieblad. Speciale editie Eindhoven.

Franz W. Kaizer 1990, ‘Jef Geys: n° 250,’ L’art en Belgique. Flandre et Wallonie au XXe siècle. Un point de vue, exh. cat., Paris: Musée d’Art Moderne de la Ville de Paris, p. 456.

Inzicht / Overzicht. Overzicht / Inzicht. Aktuele Kunst in België 1979, exh. cat., Ghent: Museum van Hedendaagse Kunst.

Luk Lambrecht 2004, ‘Een wereldkunstenaar uit Balen,’ De Morgen, April 8, p. 20.

Johan Pas 2005, Beeldenstorm in een spiegelzaal. Het ICC en de actuele kunst 1970-1990, Leuven.

‘Seth Siegelaub: Exhibitions, Catalogues, Books & Projects, Interviews, Articles & Reviews,’ Stichting Egress Foundation, http://egressfoundation.net/egress/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&id=64&Itemid=310 (accessed March 23, 2010).

Hilde Van Gelder and Helen Westgeest 2011, Photography Theory in Historical Perspective, Malden-Oxford-Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, pp. 14-63.

Jeff Wall 1995, ‘“Marks of Indifference”: Aspects of Photography in, or as, Conceptual Art,’ in: Ann Goldstein and Anne Rorimer (eds.), Reconsidering the Object of Art: 1965-1975, Los Angeles/Cambridge (Mass.), pp. 247-267.

Griet Wynants 2011, ‘Exhibition’, in: Press file of the exhibition Martin Douven, Leopoldsburg, Jef Geys, Antwerp, pp. 3-5.