Digital Appropriation as Photographic Practice and Theory

Extract

The appropriated images presented in the exhibition From Here On (Arles, 2011) offer theorists many issues to elaborate. This essay juxtaposes several of these images to arguments from the history of photography theory, especially those which intend to define an aspect of this medium through referring to appropriation in one way or another. Most key works still relate to photography’s goal of visually appropriating the world through supporting or critically interrogating this aim. It is especially the availability, changeability and deformation of the digital imagery used, and the appropriated particular viewpoints of observation cameras that could be called ‘new’. Moreover, the continuously changing avalanche of images on the internet stimulated the reflection on dynamic processes of appropriation. The interactivity of the internet is, however, replaced by the working process of analogue art photography: images selected from a quantity of latent material, were printed and presented on walls, although the final products are less important than the processes of appropriation.

‘Now, we’re a species of editors. We all recycle, clip and cut, remix and upload. We can make images do anything. All we need is an eye, a brain, a camera, a phone, a laptop, a scanner, a point of view. And when we’re not editing, we’re making. […] We have an internet full of inspiration: the profound, the beautiful, the disturbing, the ridiculous, the trivial, the vernacular and the intimate. […] It changes our sense of what it means to make. […] Things will be different from here on…[1]

The manifesto formulated by the curators of the exhibition From Here On, presented in Arles in 2011, seems to function as an instruction – almost a warning – for the visitors: you should not perceive the images presented in the exhibition as you used to do; do not search for high quality photography, but realize that these images become interesting only by asking questions such as ‘what is it that I am actually looking at?’ (figs. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6 ,7, 8). The text of the manifesto does not contain the word photograph, but it is clear that all the images in the exhibition are related to photography in one way or another. The manifesto particularly invites reflection on how to deal with the load of images we are continuously confronted with on the internet, and the differences between ‘taking’, ‘making’, and ‘appropriating’ images (photographs). Consequently, the appropriated images presented might have disappointed connoisseurs of photography, but they offer photography theorists multiple issues to elaborate on. Most scholars, however, will not agree on the main statement in the manifesto, suggesting that ‘things will be different from here on’. We can find quite similar tendencies in the visual arts of the twentieth century, called ‘ready-mades’ or ‘appropriation art’. In the essay that accompanies the manifesto in the catalogue From Here On, Clément Chéroux confirms that the images in the exhibition can be considered as a development of those trends, but what makes them different would be the role played by the internet: ‘a phenomenon comparable to the advent of running water and gas in big cities in the nineteenth century. We all know just how thoroughly those amenities altered people’s way of life in terms of everyday comfort and hygiene – and now, right in our homes, we have an image-tap that is refashioning our visual habits just as radically.[2]

The internet ‘image-tap’ not only offers us an avalanche, but also a great multiplicity of images. Most of them can be identified either as vernacular images or professional records meant for commercial use.[3] Only a small percentage could be called art photography or documentary photography. Most overviews of the history of photography suggest that the majority of photographs belong to the latter categories. Theorists such as Geoffrey Batchen have stressed that we should reconsider the history of photography through considering what has always been excluded from photography’s history: ordinary photographs that constitute the vast majority of photographs made.[4] This preponderance is increasing in the digital era; surfing on the internet makes us clearly aware of that disproportion, also to be found in the kinds of appropriated images discussed in this essay.

This essay does not intend to position the ‘From Here On images’ in the history of modern art or photography. Far more interesting, in my opinion, is to juxtapose these images to some arguments from the history of photography theory, especially those arguments which aim to define an aspect of the medium photography through referring to appropriation in one way or another. The goal of this strategy is to clarify what is already existing practice in photography with regard to appropriation, and what might be called quite ‘new’ in the images under discussion. The images selected for my argument are divided into three categories: ‘appropriating images from observation and recording systems’, ‘appropriating iconic images’ and ‘appropriating the world’. Finally, I will address the influence of digitization and the use of the internet on the current revival of appropriation strategies.

The action of the traditional photographer is called ‘taking a photograph’. The authors of the manifesto seem to prefer the term ‘making images’ for their practice, but if we define ‘taking’ as ‘making your own’ or ‘appropriate’, and ‘making’ as a creative process starting from scratch, the verb ‘taking images’ seems to be more correct in this case than ‘making’ them. Even the phrase ‘taking photographs’ might be suitable, although the authors – like some other theorists – prefer the term digital imagery to digital photography.[5] In the volume with the intriguing title Where is the Photograph? (2003) that deals with recent changes in appearances of photographs, a preference appears for the term ‘the photographic’ rather than ‘photography’. That term was already part of debates in the 1920s and 1930s, but its definition changed through time. In his contribution to the 2003 volume, Olivier Richon explains that the photographic nowadays entails a position calling into question the status of origins and originality in terms of what is pictured and who pictures it. The adjective photographic means ‘of’ or ‘relating to’ photography. An adjective can participate in the description of an object; by making a noun out of the adjective, the dependence of the object has been solved. As a result, Richon claims that ‘the photographic’ suggests an activity and a process rather than referring to objects that belong to a specific discipline.[6] This definition of ‘the photographic’ appears to be applicable to the works discussed. William J. Mitchell’s definition of digital photography as a medium that privileges fragmentation, indeterminacy, and heterogeneity, and that emphasizes process or performance rather than the finished object comes close to Richon’s characterizing of ‘the photographic’, and is therefore also applicable to most of the key works, but certainly not, in my opinion, to digital photography in general.[7]

As a general introduction to reflections on appropriation in theoretical debates on photography, I will mention several views. Already in the late nineteenth century some texts on photography suggested that a photograph claims something of its referent by means of its recording. The famous French photographer Félix Nadar, for instance, mentioned that his friend Honoré de Balzac had an intense fear of being photographed. According to Balzac’s theory, every time someone had his photograph taken, one of the spectral layers was removed from the body and transferred to the photograph. Repeated exposures would entail the unavoidable loss of subsequent ghostly layers, that is, the very essence of life.[8] Most literal, however, is Susan Sontag’s statement in her frequently quoted book On Photography (1977): ‘To photograph is to appropriate the thing photographed. It means putting oneself into a certain relation to the world that feels like knowledge – and, therefore, like power.[9] Fred Ritchin added to that quote in his 2009 book After Photography that ‘in the digital realm, where each image is a malleable mosaic, the distance is magnified. The photograph, no longer automatically a recording mechanism, is not as able to “appropriate the thing photographed” as much as to simulate it. […] What is appropriated is often someone’s else’s photograph, one of several postmodern strategies to which the digital lends itself.’[10]

Several texts on the functions of photographs discuss the consequences of appropriation by a particular genre. A well-known example is Rosalind Krauss’s comparison of Timothy O’Sullivan’s photograph Tufa Domes, Pyramid Lake, Nevada (1868) – later praised for its mysterious, silent beauty – with its lithographic copy produced for the publication of Clarence King’s Systematic Geology in 1878. In order for the image to function within the discourse of empirical science, the ordinary elements of topographical description had to be restored. Nowadays we tend to assess this image as visual banality.[11] How much the meaning and aim of a photograph can vary as a result of changing contexts becomes particularly clear in Veronica Hekking’s discussion of the multiple appropriations of Chas Gerretsen’s photo portrait of Augusto Pinochet.[12] In the From Here On exhibition the visitors are confronted with images which are withdrawn from their function on the internet and presented in the context of an exhibition. The images that will be discussed in the second category were even part of another context before they were uploaded on the internet.

Ritchin observes a relationship between how we deal with images nowadays and the great quantity of images we are confronted with. The manifesto also relates the appropriation of images to the abundance of available images: ‘We have an internet full of inspiration […] It changes our sense of what it means to make.’ In 2009, on the basis of available figures, Ritchin predicted that by the year 2010 it is expected that we will be producing half-a-trillion photographs annually.[13] Whether that number is correct, and whether we already exceded that number in 2012, will not bother many of us: the number is already too huge to imagine.[14] Most of the images will not be saved: digital images not only can be produced more easily and faster than analogue ones, they can also be thrown away more easily by pressing a button. According to John Tagg the acceleration in the circulation of images already started in the 1880s with the introduction of the half-tone plate: the problem of printing images immediately alongside words, and in response to daily changing events was solved. Not only had the availability of images increased (and with it the possibility to easily ‘appropriate’ them), but ‘the era of throwaway images had begun’ too.[15] We may wonder if most of the images presented in the exhibition would have disappeared if they would not have been appropriated (‘rescued’ or ‘recycled’) by the artists. Probably most beholders would not worry if the kinds of internet images used by these artists will be deleted from the digital highway, because the images themselves are not highly significant or meaningful; only through isolating the appropriated images from the context of the internet, by printing, enlarging or adapting them, and presenting them in the contemplative ambiance of an art exhibition, are interesting reflections provoked.

Appropriating images from observational and archival systems

Already in the 1870s several photographers were considered to be collectors of unknown places. For instance Carleton Watkins and Timothy O’Sullivan were asked to ‘bring under control’ – almost to ‘appropriate’ – the quite inaccessible Western USA for the American government and its citizens by means of visual knowledge. Complementary to the cartographers, the photographers were visually mapping unknown places. Archives containing photographs increased in the late nineteenth century and twentieth century, as Allan Sekula emphasizes in his reflection on images in archives.[16]Archiving our living space expanded immensely through the Google Street View system. In 2007 Google launched Street View, intending to map and document every street in the USA. Cars drove every street and recorded them by means of nine cameras mounted on their roofs. The standard height of the cameras at 8.2 feet provides a point of view which is higher than ‘eye level’. That causes the impression that we are not walking or driving by car through the streets but are floating across cities eight feet high above the streets (fig. 1).

|

Fig. 1. Doug Rickard, #82.948842, Detroit, MI. 2009, 2010, from series A New American Picture © Doug Rickard |

Doug Rickard (1968) works in the footsteps of the geographer-photographers and street photographers from both the nineteenth and twentieth century. He admires their work, but had to conclude that most of these photographs leave out images of the parts of the USA that Americans are not proud of.[17] Rather than travelling to those places to record them, Rickard stayed at home and used Google Street View as vehicle for his series of street photography (fig. 1).

Rickard appropriated the images, but are these Internet images free from authorship or are they owned by Google? It is rumoured that Google is accusing Rickard of illegal appropriation of these images. Google, however, appropriated the images of houses from their owners and portraits of people on the streets without asking them for permission. I will not delve into this aspect of appropriation, but the complexity of the copyright issue, the often mentioned comparison of the internet to archives, and Rickard’s reference to Walker Evans[18] made me think of an observation by Allan Sekula in ‘The Body and the Archive’: ‘Evans’s book sequences, especially in his 1938 American Photographs, can be read as attempts to counterpose the ‘poetic’ structure of the sequence to the model of the archive. Evans began the book with a prefatory note reclaiming his photographs from the various archival repositories which held copyright to or authority over his pictures.[19]

Next to legal aspects of appropriation, Rickard, GSV, and Evans had to deal with ethical aspects of appropriating the visual appearances of their models without asking for permission. With regard to recording people in public spaces, in her 1988 essay ‘Access and Consent in Public Photography’ Lisa Henderson advised photographers on how to proceed, assuming that most photographers want to avoid appearing sneaky or suspicious. Especially regarding the kinds of places Rickard is interested in, Henderson argues that when it is apparent that race or economic status is different from the established community’s, when the photographer arrives as a mechanically equipped observer, prepared to leave with recorded images that probably does not reflect the community’s sense of itself and which, most likely, its members will never see, the relationship between photographer and the recorded people is problematic.[20] Rickard has been even more invisible than photographers who used a candid camera, because he did not visit or record the places himself: this makes his relationship to the ‘appropriated’ people even more impersonal.

Whereas Rickard intended to draw attention of middle class people to unknown places in the USA through isolating images from GSV and presenting them, in Dutch Landscapes Mishka Henner (1976) presents his public with places that have to stay invisible (fig. 2). These ‘landscape photographs’ are recorded by satellites and show locations censored by authorities, hiding significant sites including army bases. Photographs taken by satellites make almost every spot on the world visible. Henner demonstrates that particularly the very small number of places which we are not allowed to see at most challenges our urge to ‘visual appropriation’ of those places.

The attraction of photography is often related to the tension between ‘making present through owning an image’ and ‘stressing absence and distance’, especially with regard to portrait photography. The enigmatic aerial imagery that Secretary of State Colin Powell certified as proving the existence of weapons of mass destruction in Iraq proved that the tension between presence and absence is also applicable to ‘landscape photography’.

Henner’s and Rickard’s series show us the impersonal character of the images produced by observation systems. Conversely, Jens Sundheim (1970) succeeded in making impersonal images of this sort more personal. He acted as a traveller, posing in five continents and hundreds of locations standing in front of web cams. Subsequently, he downloaded these images from the internet as a means of creating a document of his travels (fig. 3). Who is appropriating what here? An observation camera continually records a specific place and traps everyone who enters its domain. The photography theorist Henri Van Lier compared the photographer with a hunter who captures his victims in traps; a strange kind of hunter-trapper, however, one who instead of catching his prey seems more interested in merely catching its traces.[21] Sundheim travels from trap to trap: the photographer let himself be trapped to produce ‘self-portraits’. He appropriated the images he did not record himself, but had staged himself. Moreover, Sundheim does not observe the world, as photographers usually do, but investigates how the world observes him.

|

Fig. 3. Jens Sundheim, Dortmund front door House Entrance, Dortmund, Germany, 2007, from series The Traveller © Jens Sundheim / www.the-traveller.org |

As a result of the location of observation cameras, often just under the ceiling, the points of view are quite unusual in comparison with most photographs in the history of photography which indicated the position of a photographer. Although the images of Rickard, Henner and Sundheim differ in quite a few respects, it is remarkable that they have in common that the observation systems used record from a viewpoint that can hardly be shared with the eye of a photographer. Moreover, quite similar to the common working process in photography, their work started with a camera that appropriated images from the world in front of the lens, of which some were subsequently selected, printed and presented. The application of this traditional working process is quite remarkable, especially if we think of Peter Lunenfeld’s statement that the ‘computer allows the artist to morph, clone, composite, filter, blur, sharpen, flip, invert, rotate, scale, squash, stretch, colorize, posterize […] While photography has always had an inherent mutability, digital photograph is so inextricably linked to the other elements of computer graphics that the formerly unique qualities of photography as photography disintegrate.[22] Jacques Clayssen even concludes in his essay ‘Digital (R)evolution’ that the language of digital technology actually is exactly the same as the language used in the production of animated pictures, sounds, writing and graphics, suggesting that one may expect a new kind of images rather than traditional analogue photograph-like images.[23] With regard to appropriation as central term of this essay, we may conclude that the three artists discussed in this section not only appropriated images from observation systems, but also appropriated the traditional physical form of manifestation of analogue photographs.

Appropriating iconic images

The source material and results of the appropriation actions by Pavel Maria Smejkal (1957) and Hermann Zschiegner (1971) are different from those in the previous case studies. These artists searched for images from the canon of analogue photography. Smejkal’s series Fatescapes consists of iconic images from the history of photography of the last five decades which showed us tragedies. Smejkal has stripped out the main event and left us with the background for it (fig. 4).[24] Despite this removal, the images are surprisingly recognizable, especially due to the presentation as sequence of icons. We even think that we ‘own’ these iconic images because they are part of our collective cultural memory. However, this series also confronts us with the fact that the images have already partly left our memory: we are not able to recall all details.

The iconic images used for this series are not only some of the most reproduced images in surveys of histories of photography, but were also already earlier appropriated by artists and in less or even more manipulated versions. In most cases the focus is on the main event in these photographs. In Smejkal’s series the focus shifts from the news events to the neutral, uninteresting locations, which have become meaningful places as a result of what took place there in the past. The viewer experiences a ‘revisiting’ of that place in the present. What happened not only became history, but also part of our visual collective memory, though not as a report of a particular dramatic event anymore, but for many people unfortunately only as ‘iconic image’.[25]

Although Hermann Zschiegner also appropriates iconic images, his strategy and results are quite different. In +Walker Evans + Sherrie Levine he demonstrates how the internet disseminates iconic analogue images that are appropriated and uploaded by internet users (fig. 5). Zschiegner searched on the internet for the photograph by Walker Evans that not only become an icon in the history of photography, but also became famous as one of the classic pictures appropriated by Sherrie Levine. Artists such as Levine became celebrated in the international art world of the 1980s for their ‘appropriation art’: they appropriated iconic images and presented them as their own work. The effect of appropriating well-known images was that it was immediately clear that the artist reproduced an image made by someone else. Levine even added the name of the original photographer in the title. Subsequently, Zschiegner mentions both names.

|

Fig. 5. Hermann Zschiegner, http://home.comcast.net, from series +Walker Evans + Sherrie Levine, 2008 © Hermann Zschiegner |

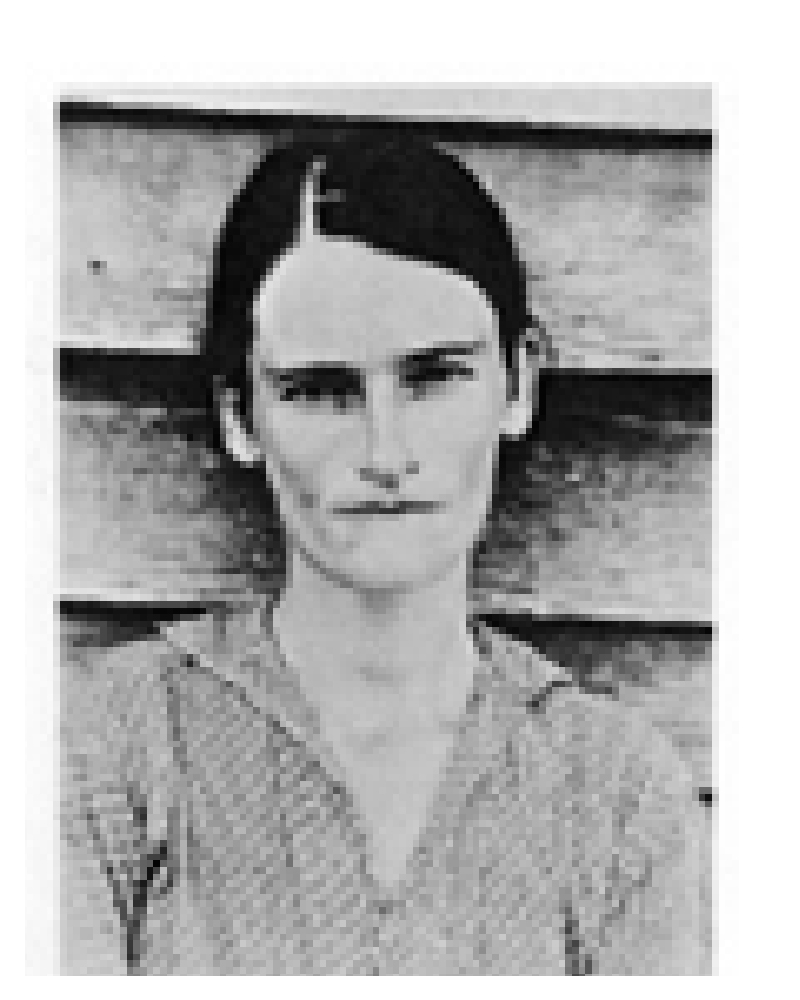

In her essay ‘Winning the Game When the Rules Have Been Changed’ Abigail Solomon-Godeau states that, when reproduced next to each other, one cannot see any difference between the original photographs and Levine’s rephotographed versions of them. Were we, however, to put the actual vintage prints next to Levine’s rephotographed prints a certain amount of difference – such as in details and sharpness – would be apparent.[26] But most people know photographs mainly from reproductions. Contrary to this loss of difference resulting from reproduction, the Google image search ‘+Walker Evans + Sherrie Levine’, conducted by Zschiegner on 24 July 2008, presented both images in a surprising variety of deformations. Zschiegner printed all twenty-six ‘portraits’ of Allie Mae Burroughs and added titles consisting of file size, pixel aspect ratio and URL of each image as frame of reference. Only by reading the file names one can identify whether we are looking at Evans’s or Levine’s work: the differences between all images made it harder rather than easier to identify them.

We might say that Levine and Zschiegner are confiscators or plagiarists. Solomon-Godeau, however, concludes that Levine does not make photographs, she takes photographs, and this act of confiscation generates a complex analysis and critique of the forms, meanings and conventions of photographic imagery (particularly that which has become canonized as art). More specifically with regard to her rephotographs of Walker Evans’s FSA photographs, Solomon-Godeau stresses that Levine, who made copy prints of copy prints of these pictures, underlines the cultural and representational codes that structure our reading of the Great Depression, the rural poor, female social victims, and the style of Walker Evans. The intention of such work is less about provoking feeling, than provoking thought.[27] The latter is also true for Zschiegner’s appropriation of both Evans’s and Levine’s work, which he appropriated indirectly through anonymous internet users who uploaded the images. The provoked reflections, however, focus on processes of dissemination, appropriation, and mosaic-like patterns of the digitized versions of the analogue originals, rather than on the meanings and contexts of the selected works.

Appropriating the world

Viktoria Binschtok (1972), Thomas Mailaender (1979), and Penelope Umbrico (1957) deal, although in quite different ways, with the digital era as encompassing the world. Already in the still analogue photography era of the 1970s, Susan Sontag stressed the connection between photography and the ambition to appropriate the world. Part of her argument is the relationship between photography and tourism: ‘[photographs] help people to take possession of space in which they are insecure. Thus, photography develops in tandem with one of the most characteristic of modern activities: tourism. […] Photographs will offer indisputable evidence that the trip was made, that the program was carried out, that fun was had.[28] Thomas Mailaender’s series Extreme Tourism seems to ridicule the tradition of competing with each other about the most impressive holiday photographs through inserting himself in other people’s images (fig. 6). In the 1970s we could still believe in the truthfulness of photographs. Now, more than three decades later, digital photography made it easier than ever before to manipulate images, and to even present exciting holiday photographs of holidays that never took place. Fred Ritchin underscores that advance, noting that for the tourist one of the great advantages of digital imaging is the ability to have oneself ‘photographed’ at one’s destination before leaving for vacation, thus create a ‘future travelogue’. This application of digital photography suggests that this ability only serves us for fun. Ritchin, though, also proposes more societal benefits: ‘The photograph in the digital environment can envision the future with enough realism to elicit responses before the depicted future occurs. Whereas analogue documentary photography shows what has already happened when it is often too late to help, a proactive photography might show the future, according to expert predictions, as a way of trying to prevent it from happening. […] Photography, rather than reacting to apocalypse, can now try to help us avoid them.[29]

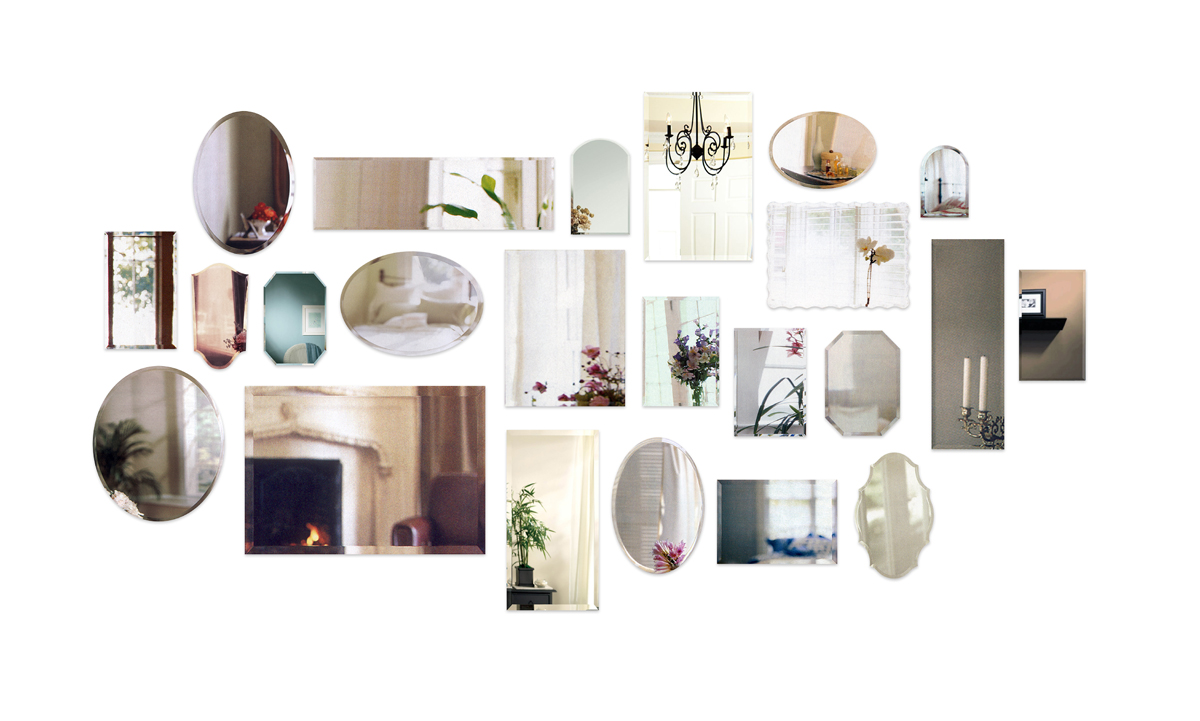

The close relationship between photography and the visible world surrounding us is also stressed in those theories of photography which describe photographs as ‘mirrors with a memory’.[30] Christian Metz emphasized in ‘Photography and Fetish’ (1985) that images in mirrors change, but photographs conserve their images: ‘Photography is the mirror, more faithful than any actual mirror, in which we witness at every age, our own aging.[31] Penelope Umbrico’s series Mirrors presents mirrors which are able to appropriate their images. Umbrico took images of mirrors for her Mirrors ( From Home Decor Sites) series directly from mail-order catalogues and brochures displaying idealized room suites (fig. 7). She digitally transformed them back into a frontal view and enlarged them to the dimensions of the actual sizes of the mirrors being sold in the catalogues. They were then hung on the wall as if they were real mirrors. The mirrors in the catalogues seem to locate the viewer within the photographed space by reflecting what would be behind him/her. Umbrico’s Mirrors even more clearly show the seductive trappings arranged in those mirrors’ reflections, which became surrogates for the missing reflection of the viewer. The viewer witnesses his/her own disappearance and replacement by saleable objects.[32]

At first sight Umbrico’s series suggest that the images played down the role of the photographer, because the images were provided by electronic sites such as Home Decor Sites. We have to realize, however, that there are almost as many photographers as images involved here; we just do not know their names. Umbrico brings them virtually together in an exhibition room.

The series Globes by Viktoria Binschtok not only mirrors the world and brings many anonymous photographers together,[33] but also quite literally shows the current globalization phenomenon by means of photographs of globes which she selected from the internet on websites of virtual auction houses where people present objects on sale (fig. 8). The collected images demonstrate how the whole world is appropriated in the private domain. The appropriation of it seems to be more important than the knowledge about the world. The same goes for the internet: having the feeling (‘power’) that we have access to the whole world seems to be more important than trying to learn as much as possible about all those places we will never visit. Binschtok not only appropriated the images of the globes from the internet, she also appropriated some of the globes on sale by ordering them. These packages are added – unopened – to the images in the exhibition room. Binschtok already put them for auction online, so the globes will continue their travel around the world as their images already did.

Conclusions

By means of comparing theoretical and visual reflections on aspects of appropriation, this essay demonstrated that the images discussed deal with appropriation in a variety of ways. The most obvious form of appropriation is taking images from the internet and presenting them (whether manipulated or not). The use of computers and the internet has already become a familiar practice in new media art, but those works invite the visitors to actively participate and turn them into co-producers rather than beholders. The artists discussed in this essay eliminated the interactivity of the internet and appropriated the working process of analogue art photography: after selecting some images from a large quantity of latent material (internet images instead of negatives), they print the images and present them on walls. However, an important difference is that the process of appropriation appears to be more important than the final products. Moreover, whereas people usually visit art exhibitions to see original images that they only know from reproductions, the From Here On exhibition mainly presents prints (‘reproductions’) of original images on the internet, which could be seen staying at home.

The references from the history of photography theory demonstrated that this medium is often characterized in terms of appropriation in one way or another. Most key works still relate to photography’s important goal of visually appropriating the world through supporting or critically interrogating this aim. The relationship with this and other aspects of appropriation in photography theory put the key works in line with this discourse. It is especially the availability, changeability and deformation of the digital imagery used, and the appropriated particular viewpoints of observation cameras that could be called ‘new’ in the projects discussed. Moreover, the continuously changing avalanche of images on the internet stimulated the artists’ reflections on the dynamic processes of appropriation.

The images under discussion in this essay appear to underscore Geoffrey Batchen’s 2001 claim that ‘photography’ today is all about the reproduction and consumption, flow and exchange, maintenance and disruption, of data.[34] Fred Ritchin wonders whether we will be able to utilize new technologies to increase meaningful information and various kinds of comprehension.[35] The question whether the photographic, with its strategy of appropriation, will be able to comply with that wish, is for the future to tell.

CV

Helen Westgeest is assistant professor of Modern and Contemporary Art History and Theory of Photography at Leiden University, the Netherlands. Some of her most recent publications are: Photography Theory in Historical Perspective : Case Studies from Contemporary Art, Malden: Wiley-Blackwell, 2011 (co-authored with Hilde Van Gelder); ‘Bridging distances across time and place in photography’ in Imaging History, edited by B. Vandermeulen, Brussels: ASA Publishers, 2011. She was (co-)editor and one of the authors of Take Place : Photography and Place from Multiple Perspectives, Amsterdam: Valiz, 2009; and of Photography between Poetry and Politics, Leuven: Leuven University Press, 2008.↑

Notes

1. Quotes from a manifesto, formulated by Clément Chéroux, Erik Kessels, Joan Fontcuberta, Joachim Schmid and Martin Parr on the occasion of the From Here On exhibition in 2011 (4 July-18 September) they curated in the photography festival Les Rencontres d’Arles. ↑

2. Chéroux et al (2011), n.p.↑

3. Vernacular photography is defined by Batchen 2001, p. 57, as ‘ordinary photographs, the ones made or bought (or sometimes bought and then made over) by everyday folk from 1839 until now, the photographs that preoccupy the home and the heart but rarely the museum or the academy.’ Some other theorists also include commercial photography for public use in their definition of vernacular photography.↑

4. Batchen 2001, pp. 57-59.↑

5. For the debate on whether digital images should still be called ‘photographs’, see Amelunxen 1996 and Van Gelder/Westgeest 2011, Introduction. Geldhoff and Krijgsman 2011, p. 11, define the kinds of images such as the ones presented in From Here On as ‘a new genre in a new photography era: the age of virtual photography in a “Googleworld”.’↑

6. Richon in: Green 2003, p. 71.↑

7. Mitchell 1992, p. 8.↑

8. Batchen 2001, p. 130.↑

9. Sontag 2002, p. 4.↑

10. Ritchin 2009, p. 32.↑

11. Krauss 1982, pp. 311-13.↑

12. Hekking 2002, pp. 409-26.↑

13. Ritchin 2009, p. 19.↑

14. Erik Kessels’s contribution to the What’s Next exhibition (in FOAM, Amsterdam, 2011) was an attempt to visualize that number. It consisted of piles of about a million images downloaded from Flickr and printed to demonstrate how many images are uploaded there in one day.↑

16. Sekula 1986, pp. 3-64.↑

17. Interview with Doug Rickard, http://vimeo.com/30357393, accessed on 20 March 2012.↑

18. Interview with Doug Rickard, http://vimeo.com/30357393, accessed on 20 March 2012.↑

19. Sekula 1986, p. 59.↑

20. Henderson 1988, p. 98.↑

21. Van Lier 2007, pp. 72, 73.↑

22. Lunenfeld 2001, p. 60.↑

23. Clayssen in: Amelunxen 1996, p. 78.↑

24. Readers who do not immediately remember the original photograph can easily find it on the internet.↑

25. For a more in-depth reflection on ‘Imaging History’, see Westgeest 2011.↑

26. Solomon-Godeau 2006, p. 152: ‘variations in tonality of the prints, amount of detail, sharpness and delicacy of the forms and shadows, etc., could then be easily distinguished.’↑

27. Solomon-Godeau 2006, pp. 152, 160.↑

28. Sontag 2002, p. 9.↑

29. Ritchin 2009, pp. 53-54, 149-150.↑

30. E.g. Siegfried Kracauer in his essay ‘Photography’ (1960).↑

32. http://www.penelopeumbrico.net/index.html, accessed on 17 March 2012.↑

33. Of all eight artists discussed in this essay, only Binschtok uses images made by amateurs. All others appropriated images taken by professionals: either professional photographers or observation systems installed by technicians. Chéroux 2011, n.p., however, emphasized that the artists on show in this exhibition have in common an upgrading of the amateur at the expense of the auteur. As a result, my selection of works is not representative of the works presented in Arles, but will be more representative for the new version of this exhibition in FoMu in Antwerp in 2012.↑

34. Batchen 2001, p. 179.↑

35. Ritchin 2009, p. 184.↑

Literature references

Amelunxen, Hubertus von, Iglhaut, Stefan, Rötzer, Florian (eds.), Photography after Photography. Memory and Representation in the Digital Age, Amsterdam/Munich 1996 (first published in 1995 as Photographie nach der Photographie).

Batchen, Geoffrey, Each Wild Idea. Writing, Photography, History, Cambridge, MA, 2001.

Chéroux, Clément, et al, From Here On, Arles 2011.

Geldhoff, Suzan, Krijgsman, Karin, Screendump #1 : On Virtual Strolls, Breda 2011.

Green, David (ed.), Where is the Photograph?, Brighton/Kent 2003.

Hekking, Veronica, ‘Een foto als voertuig van de macht. Gebruik en hergebruik van Chas Gerretsens portret van Augusto Pinochet’, in: Nelke Bartelings et al (eds.), Beelden in veelvoud. De vermenigvuldiging van het beeld in prentkunst en fotografie, Leids Kunsthistorisch Jaarboek 12, Leiden 2002, pp. 409-426.

Henderson, Lisa, ‘Access and Consent in Public Photography’, in: Larry Gloss et al. (eds.), Image Ethics : The Moral Rights of Subjects in Photographs, Oxford 1988, pp. 91-107.

Krauss, Rosalind E., ‘Photography’s Discursive Places: Landscape/View’, Art Journal 42 (1982) 4, pp. 311-319.

Lunenfeld, Peter, Snap to Grid : A User’s Guide to Digital Arts, Media, and Cultures, Cambridge, MA, 2001 (first published in 2000).

Metz, Christian, ‘Photography and Fetish’, October 34 (1985), pp. 81-90.

Mitchell, William J., The Reconfigured Eye : Visual Truth in the Post-Photographic Era, Cambridge, MA, 1992.

Ritchin, Fred, After Photography. New York 2009.

Sekula, Allan, ‘The Body and the Archive’, October 37 (1986), pp. 3-64.

Solomon-Godeau, Abigail, ‘Winning the Game When the Rules Have Been Changed : Art Photography and Postmodernism’, Screen 6 (1984), pp. 88-102. Reprinted in Liz Wells (ed.), The Photography Reader, London/New York 2006, pp. 152-163 (first published in 2003).

Sontag, Susan, On Photography, London 2002 (first published in 1977).

Tagg, John, The Burden of Representation, Amherst 1988.

Van Gelder, Hilde, Westgeest, Helen, Photography Theory in Historical Perspective : Case Studies from Contemporary Art, Malden 2011.

Van Lier, Henri, Philosophy of Photography, Leuven 2007 (translated by A. Rommens; first published in 1983 as Philosophie de la photographie).

Westgeest, Helen, ‘Bridging Distances Across Time and Place in Photography’, in: Bruno Vandermeulen, Danny Veys (eds.), Imaging History : Photography after the Fact, Brussels 2011, pp. 13-25.