At the Turning Point

Reinier van der Lingen and the tradition of photographing one’s own childrenHans Rooseboom

Extract

In 2007 the Dutch photographer Reinier van der Lingen began recording his family life, his youngest daughter Lysanne’s seventh birthday being his starting point. The series took a dramatic turn when she was hospitalized soon after that, especially as she died exactly three months after the series was started. Van der Lingen subsequently published a book called 3 maanden (3 Months), containing both photographs from before and after the diagnosis that shattered his young family. The fact that one rarely sees photographs of a young person’s life while they are going through the stages from healthiness and happiness to illness and death makes 3 maanden a remarkable and moving series. The present article describes how Van der Lingen made the series, and explores the ways in which it deviates from the tradition of how children have been photographed in past and present.

Introduction

In 2009 the Rijksmuseum Amsterdam acquired a series of sixteen photographs by the Dutch professional photographer Reinier van der Lingen (b. 1966). They are part of a much larger set of photographs that he privately published as a book called 3 maanden (3 Months) in 2008 (figs 1 to 16). Van der Lingen was trained as a photographer at the Fotovakschool in Apeldoorn (1986-91) and enrolled at the Royal Academy of Art in The Hague. His first book was followed by one on the health service in The Hague, 112 GGD Den Haag.

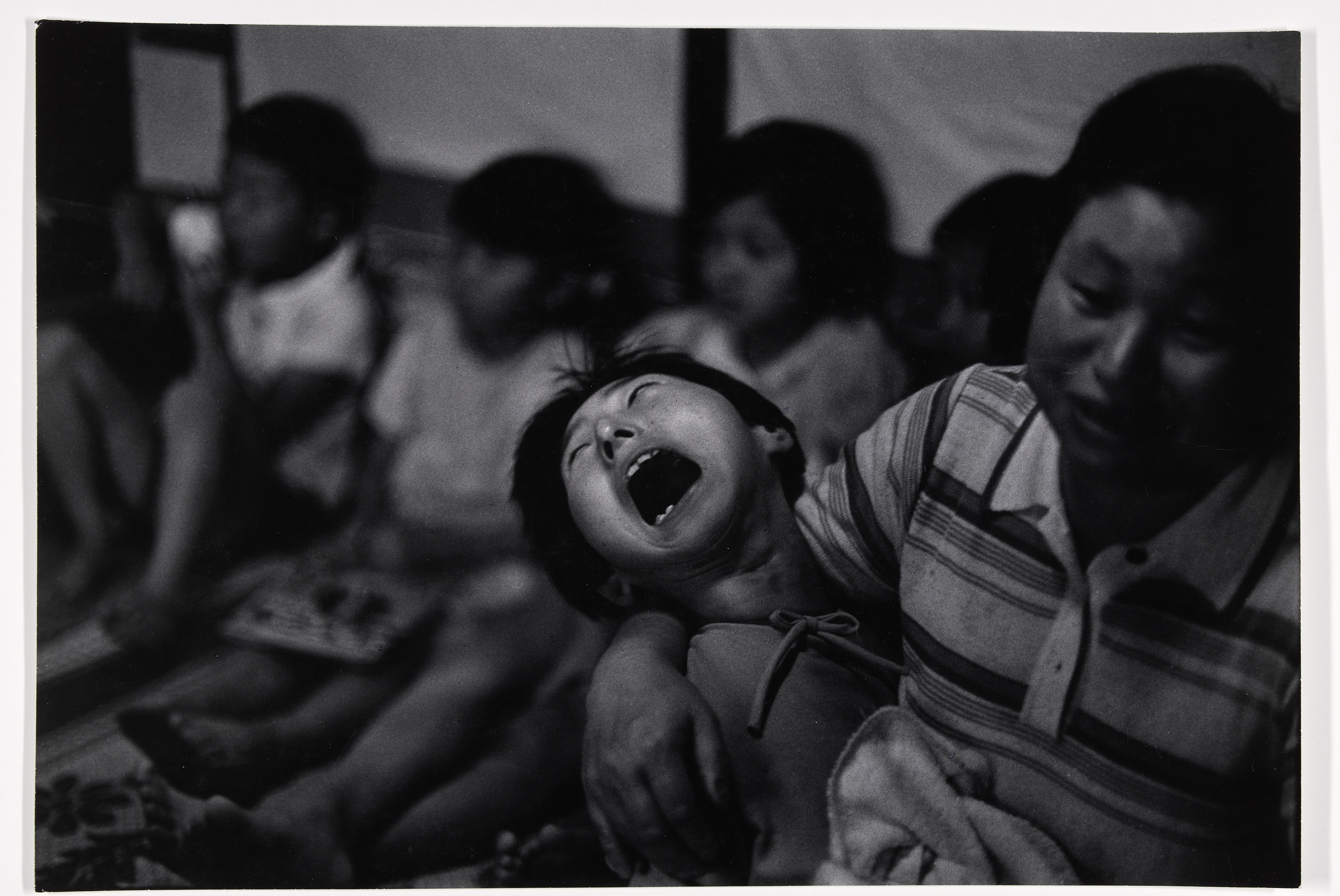

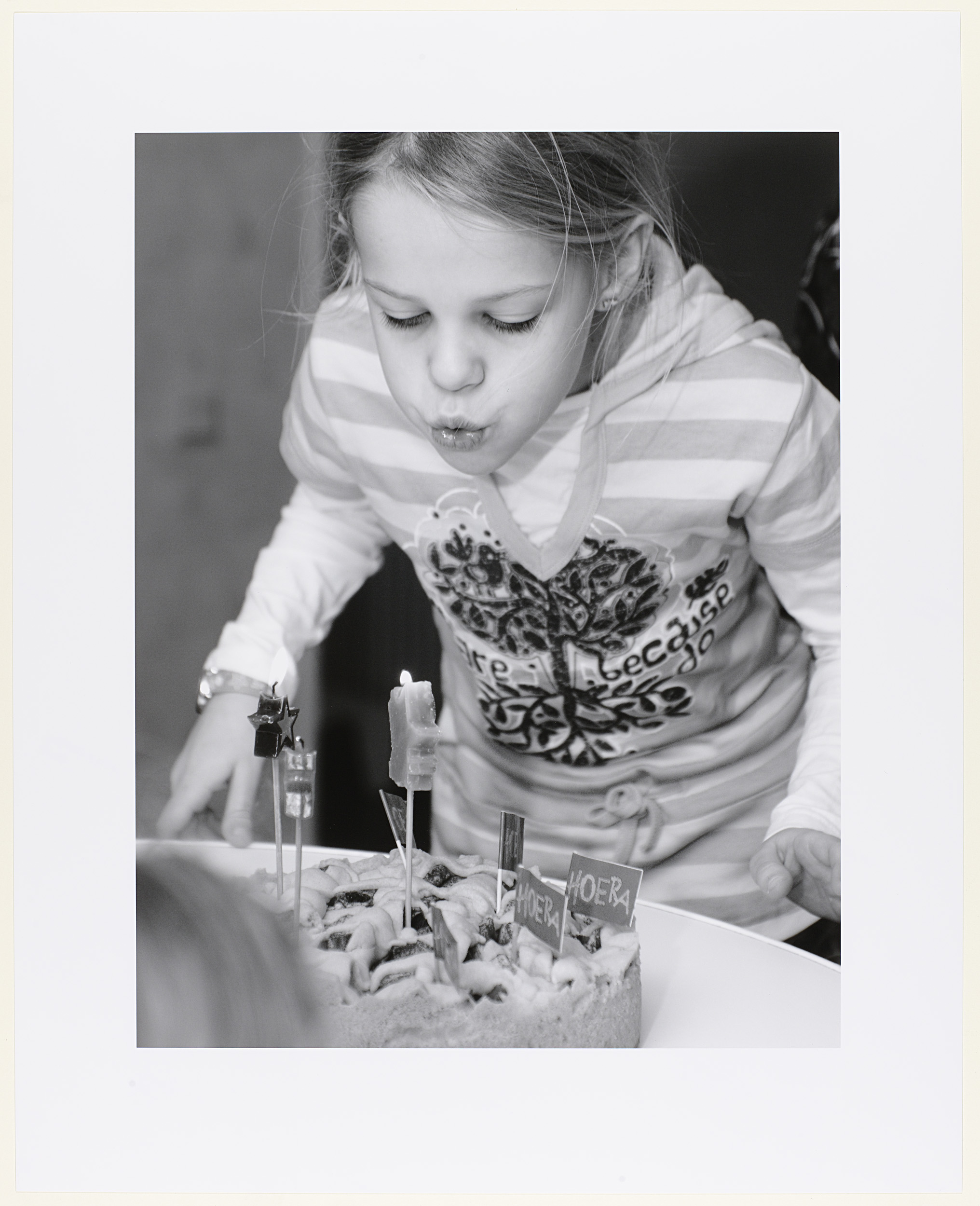

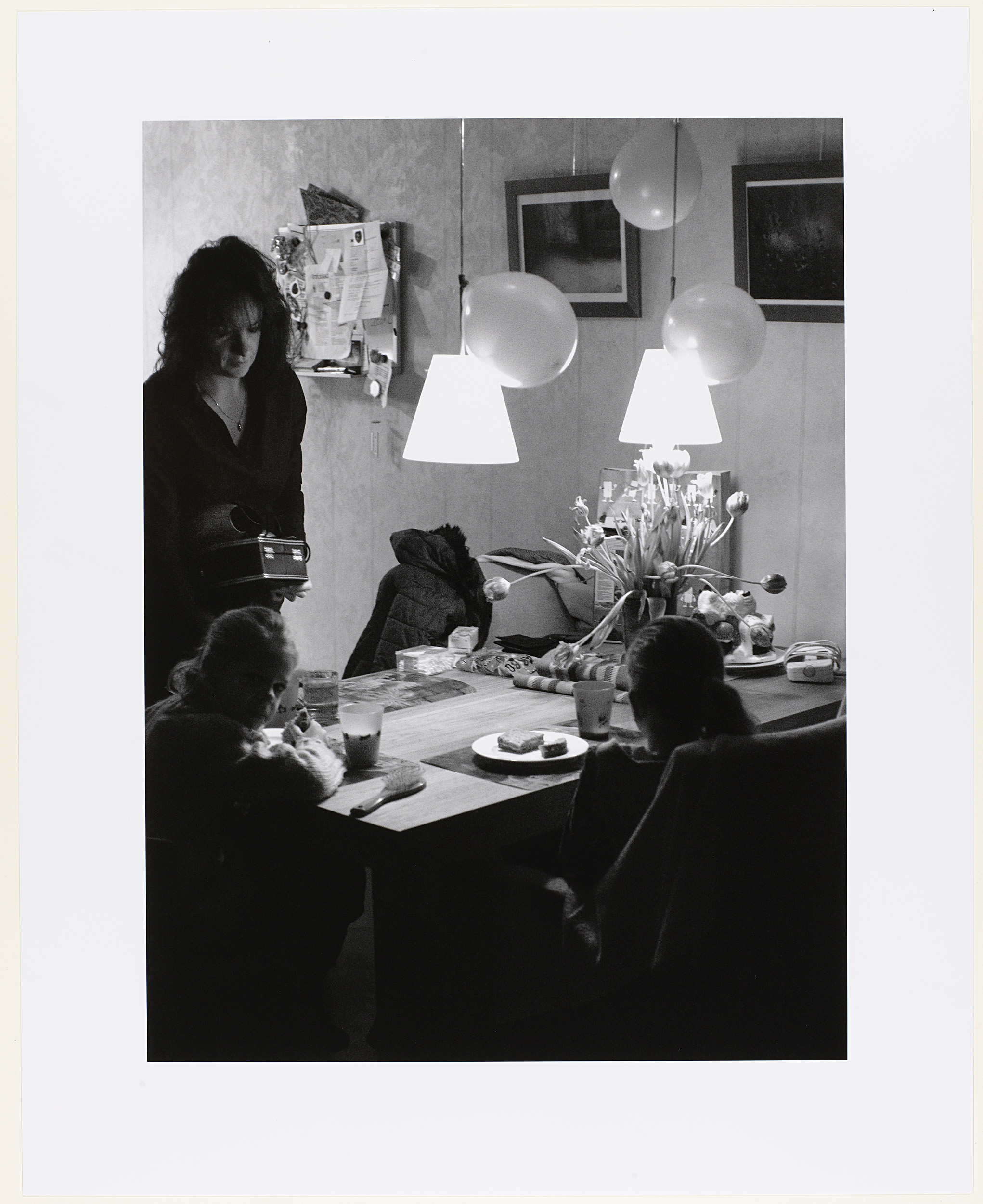

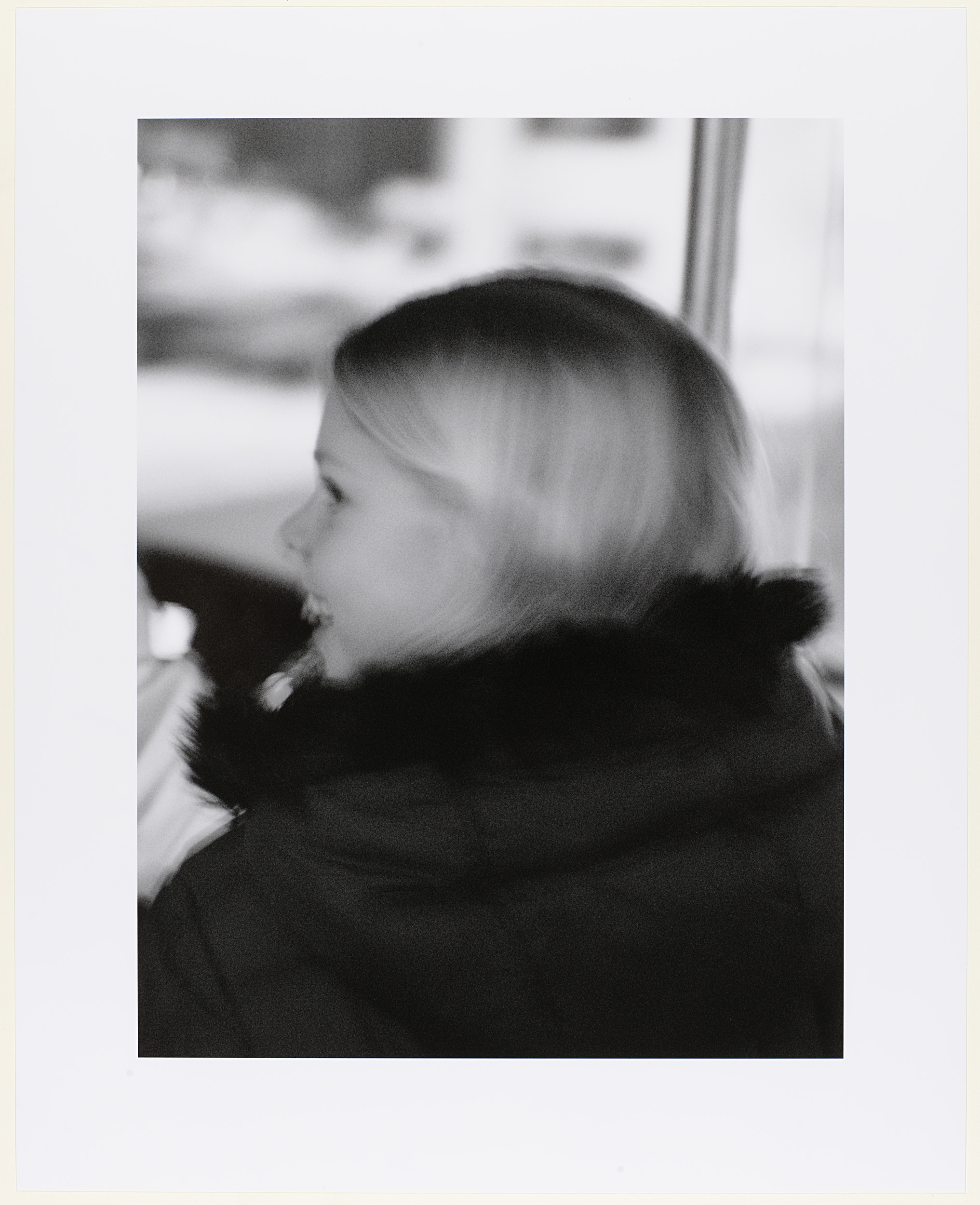

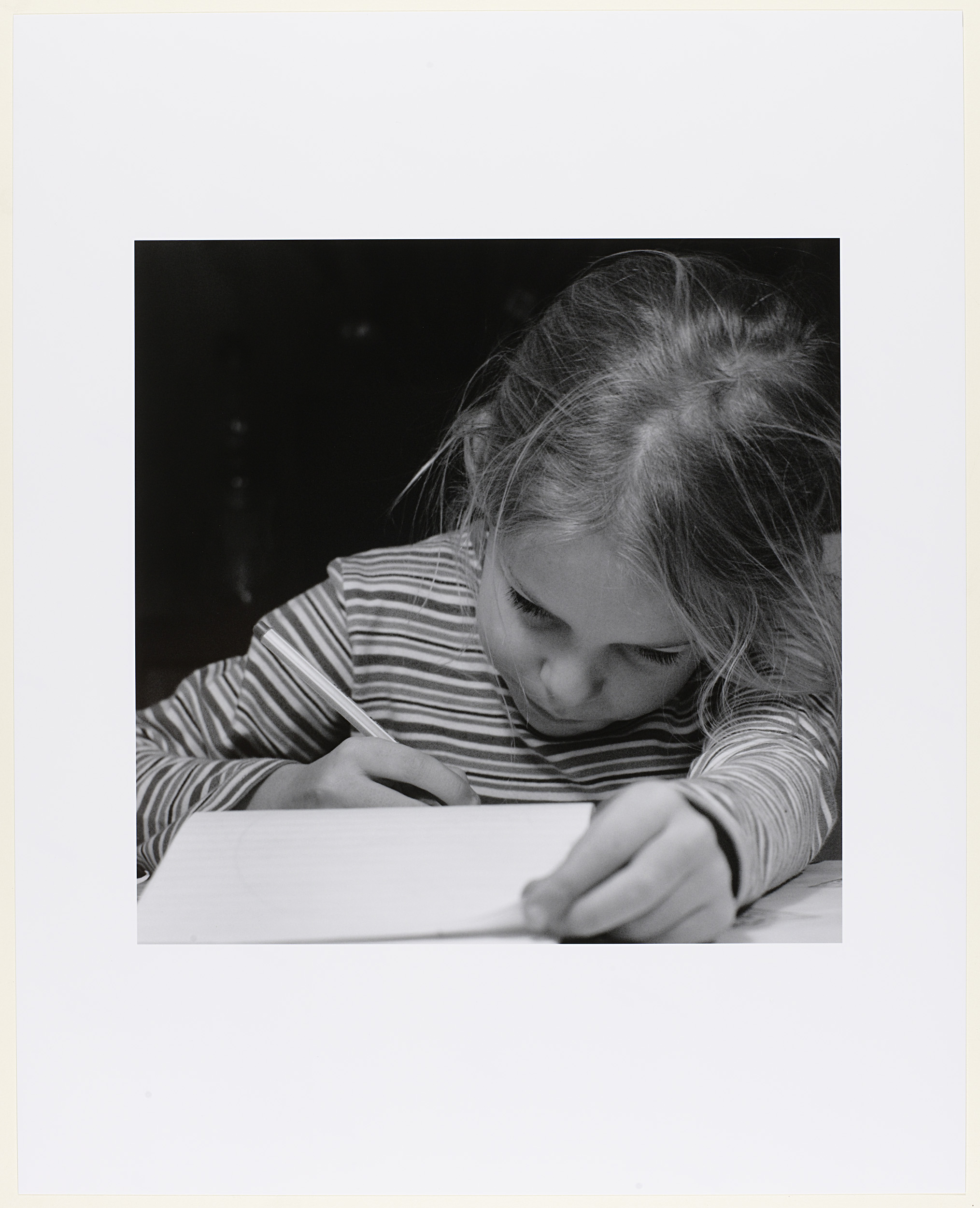

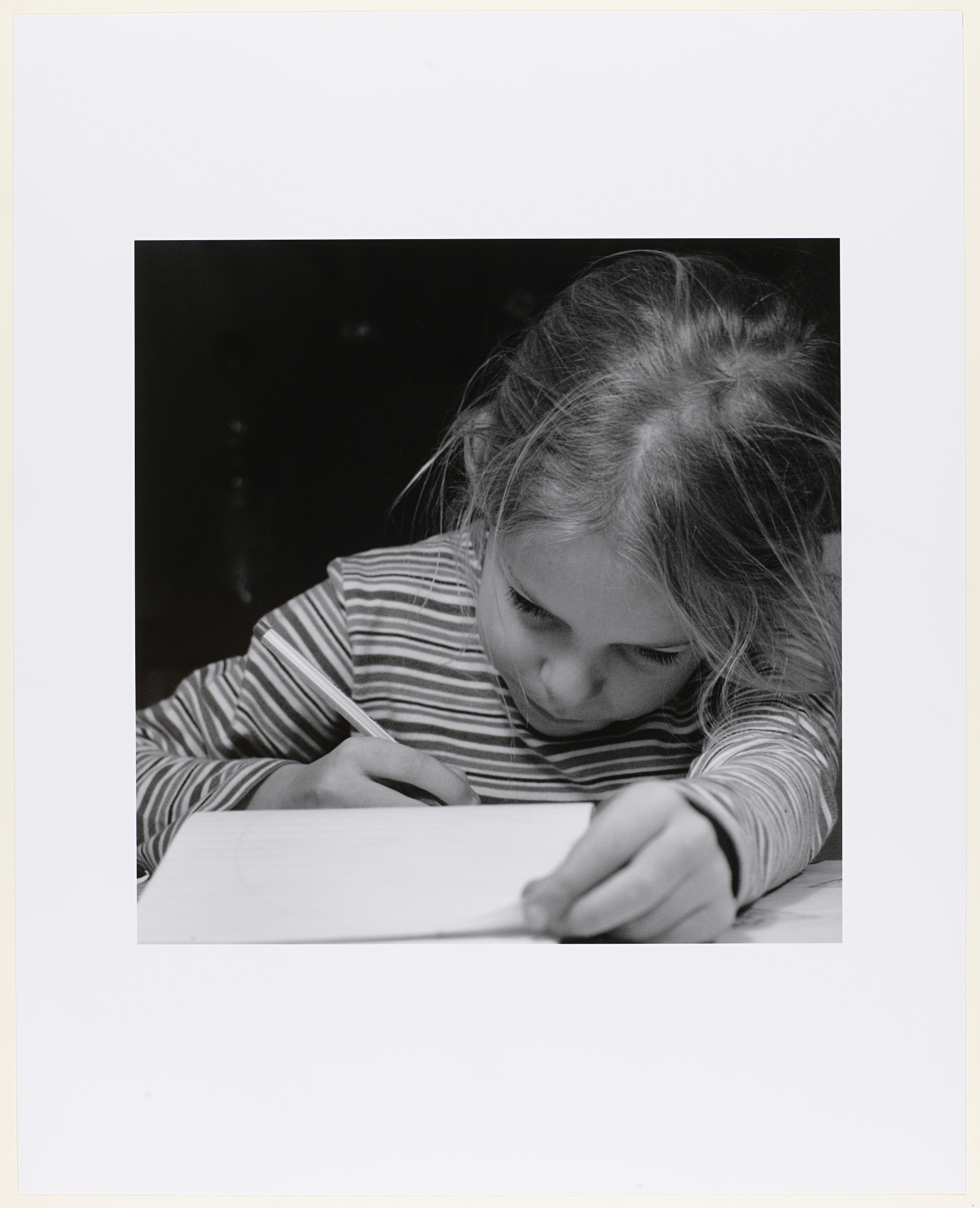

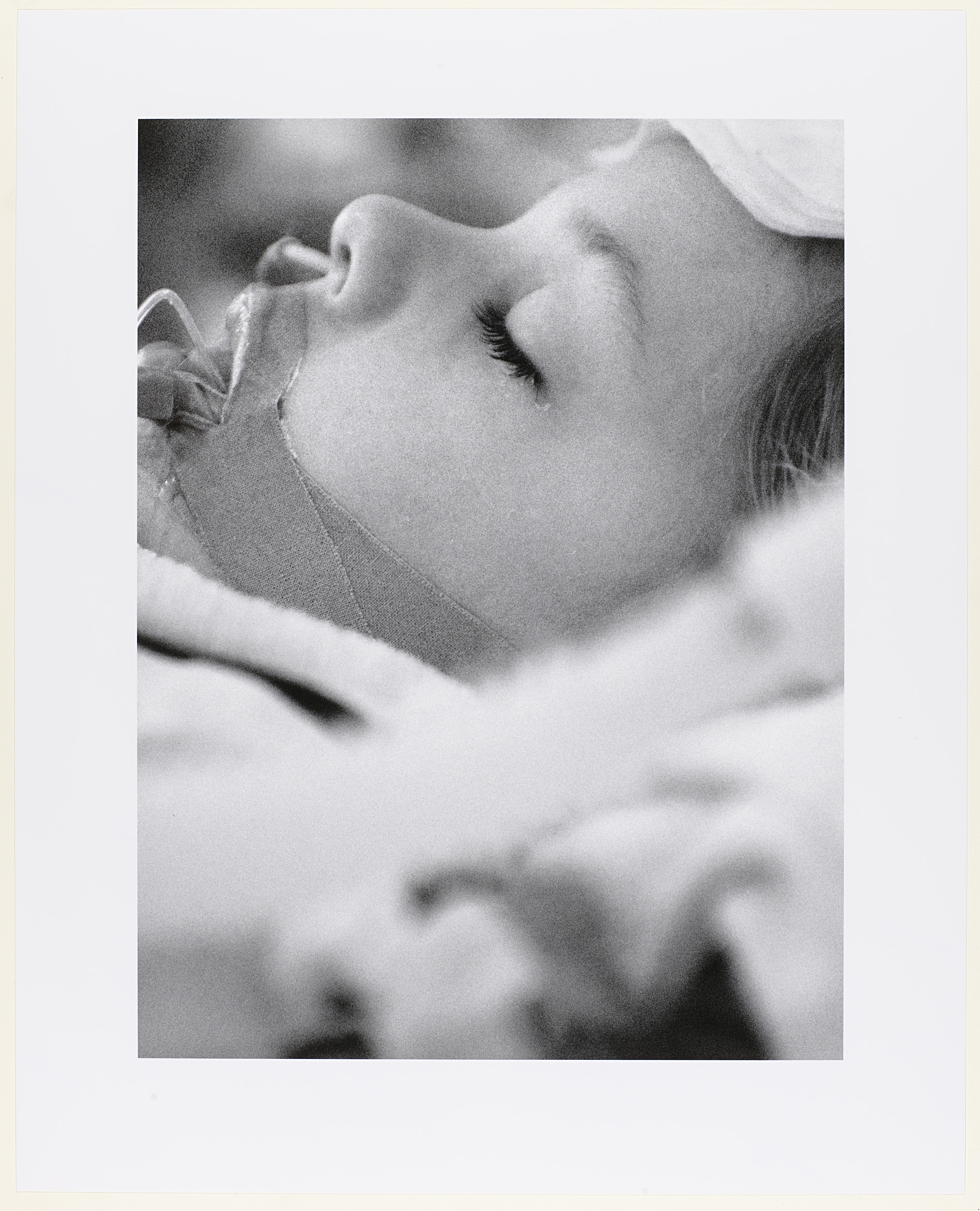

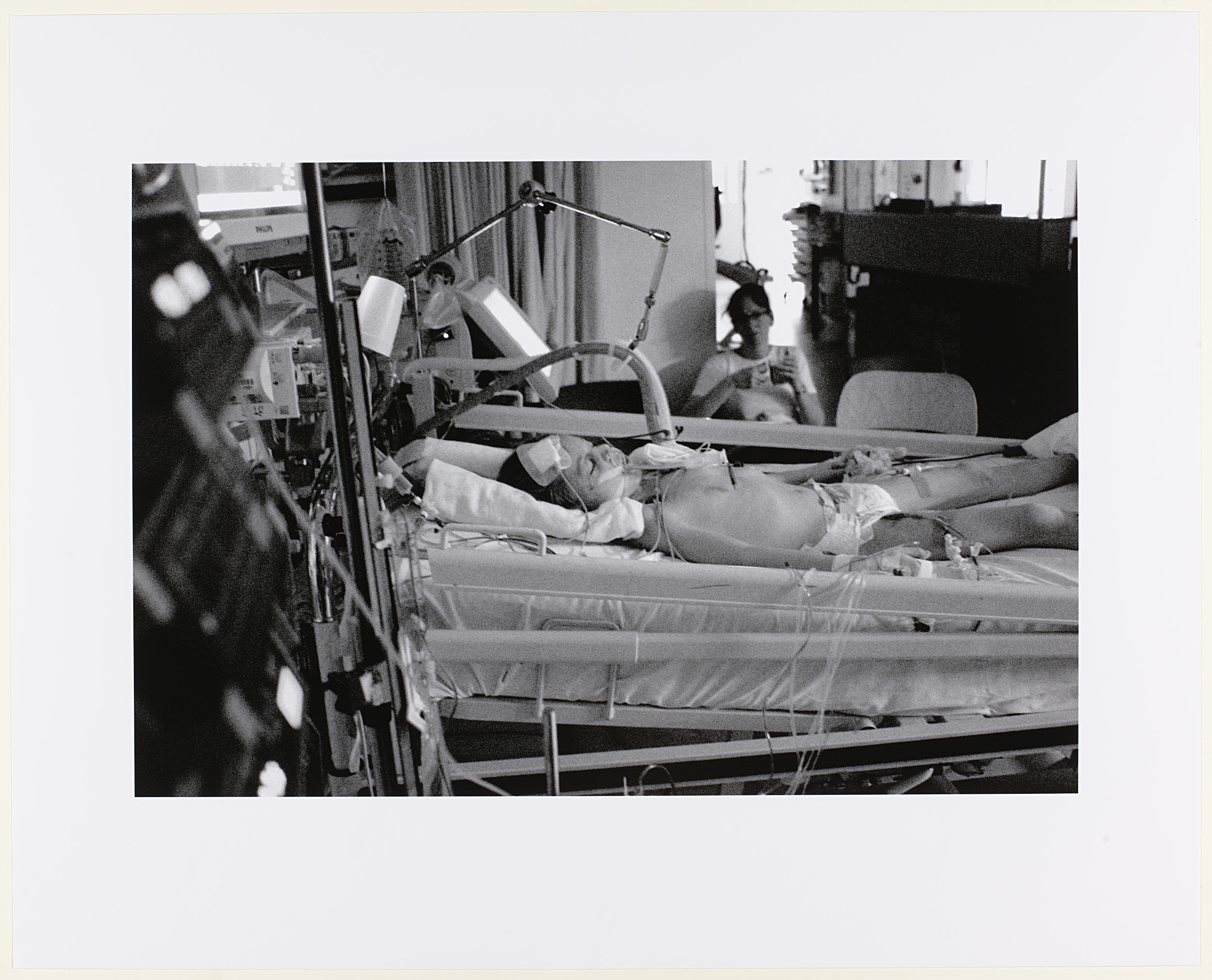

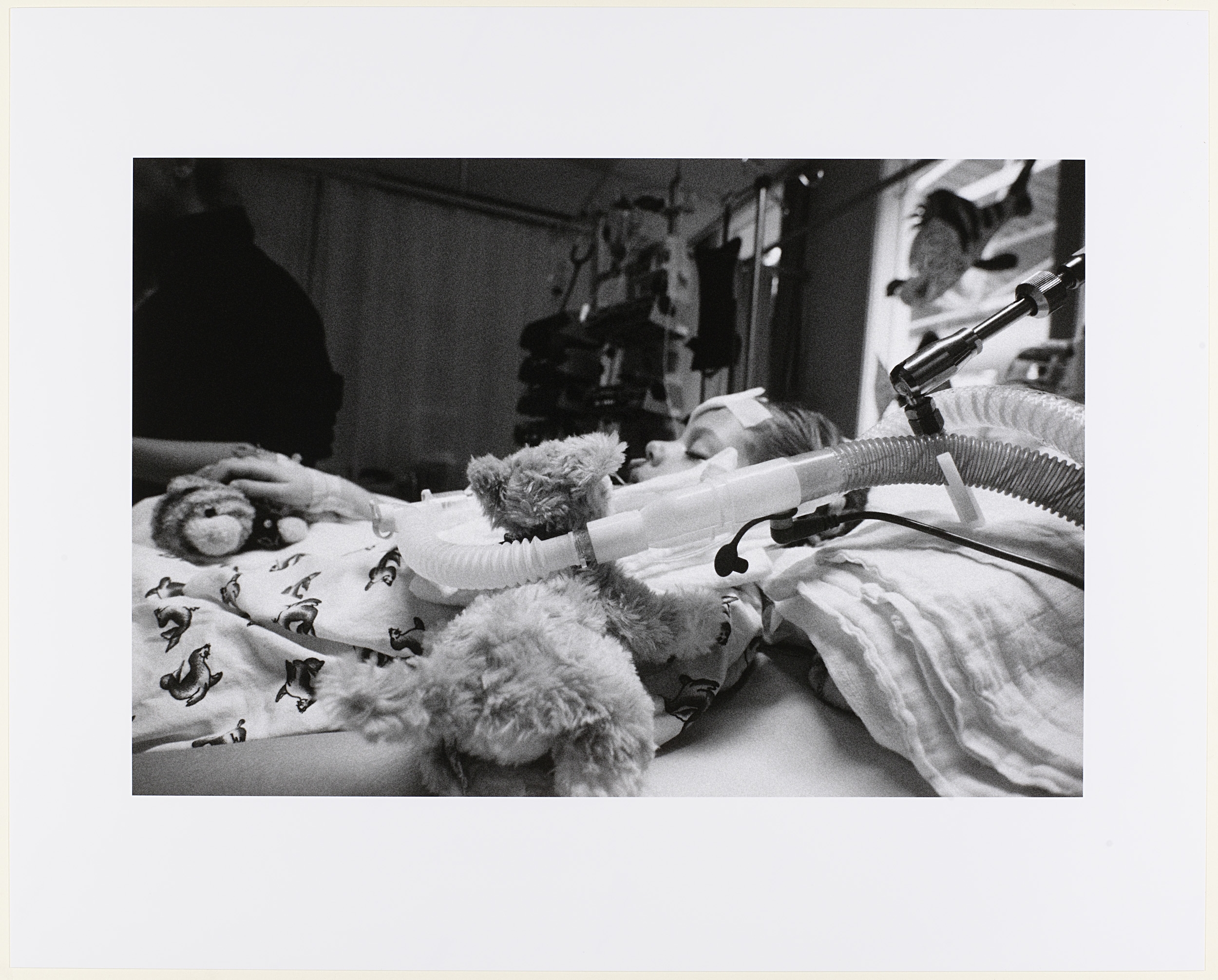

Late in 2007 Van der Lingen decided to start capturing his family life, a subject he had not covered very often up until then. His youngest daughter Lysanne’s seventh birthday – 29 December – seemed a good moment to start. We are therefore witness to, among other things, Lysanne blowing out the candles on her birthday cake (fig. 1). In the second photo in the series now at the Rijksmuseum: Lysanne, her older sister Melissa (born 1999) and her mother Margriet are having breakfast (fig. 2). Other photos show Lysanne engrossed in various activities or are intimate close-up portraits of a sweet young girl (figs 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8). So far so good, or so it seemed. The series takes a dramatic turn, however, when Lysanne is taken to hospital on 20 March 2008, where doctors determine she has a tumour in the cerebellum (fig. 9). Suddenly the girl is snatched from her familiar surroundings; the domestic character of the first photographs disappears. During her stay in the Leiden University Hospital she is attached to a respirator. There is a sharp contrast between the multiplicity of medical devices and the motionlessness of the young girl in the hospital bed, stressing how utterly sad it is to see a young person bedridden. After all, playing, running, and laughing are our primary associations with a seven-year-old.

|

Fig. 1 Reinier van der Lingen, 29 December 2007. Inkjet print, 390 x 300 mm. Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv. no. RP-F-2009-89-1 |

|

Fig. 2 Reinier van der Lingen, 2 January 2008. Inkjet print, 400 x 297 mm. Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv. no. RP-F-2009-89-2 |

|

Fig. 3 Reinier van der Lingen, 2 February 2008. Inkjet print, 399 x 300 mm. Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv. no. RP-F-2009-89-3 |

|

Fig. 4 Reinier van der Lingen, 5 February 2008. Inkjet print, 399 x 300 mm. Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv. no. RP-F-2009-89-4 |

|

Fig. 5 Reinier van der Lingen, 2 February 2008. Inkjet print, 267 x 400 mm. Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv. no. RP-F-2009-89-5 |

|

Fig. 6 Reinier van der Lingen, 3 March 2008. Inkjet print, 300 x 400 mm. Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv. no. RP-F-2009-89-6 |

|

Fig. 7 Reinier van der Lingen, 1 February 2008. Inkjet print, 300 x 300 mm. Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv. no. RP-F-2009-89-7 |

|

Fig. 8 Reinier van der Lingen, 20 February 2008. Inkjet print, 299 x 300 mm. Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv. no. RP-F-2009-89-8 |

|

Fig. 9 Reinier van der Lingen, 20 March 2008. Inkjet print, 268 x 400 mm. Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv. no. RP-F-2009-89-9 |

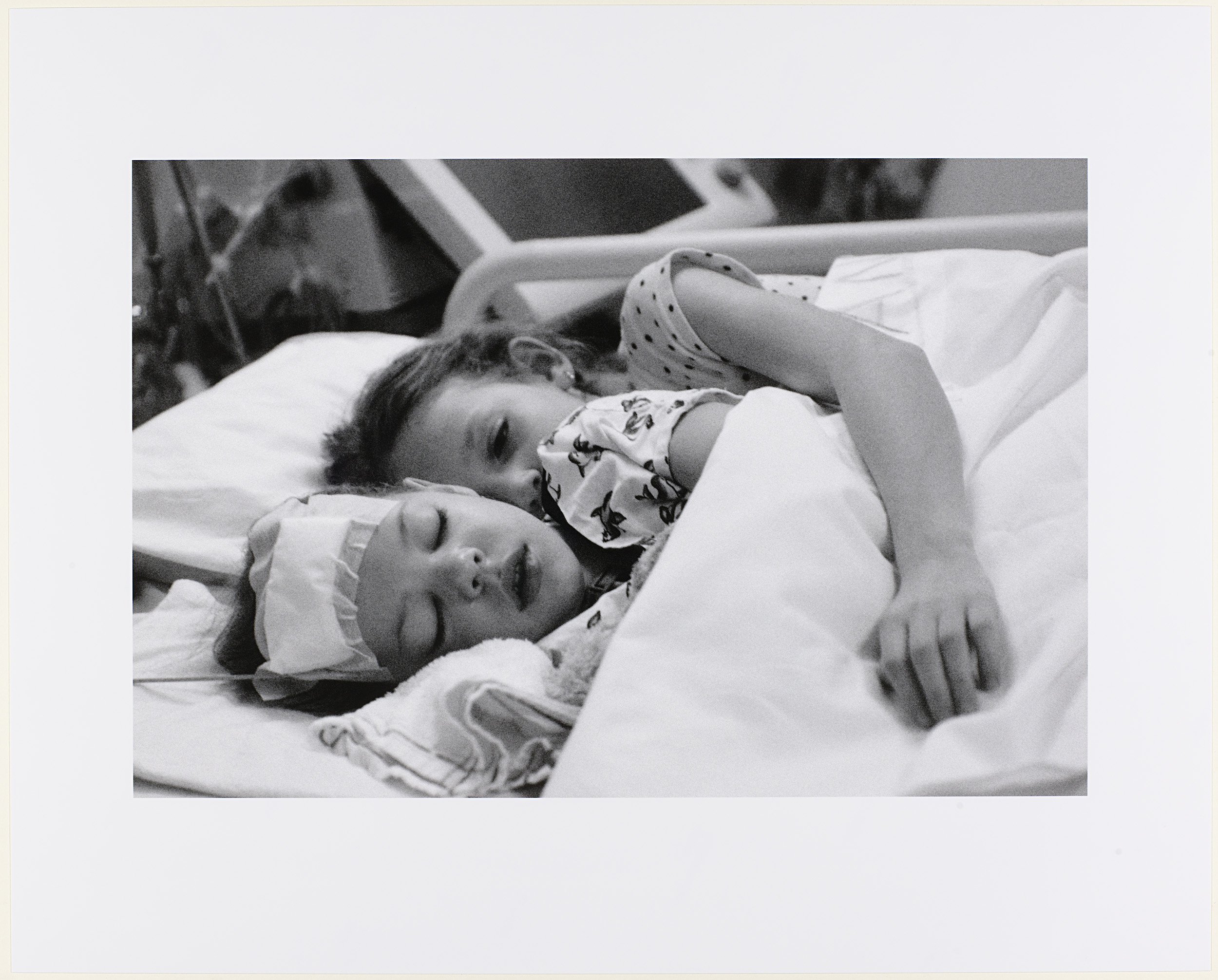

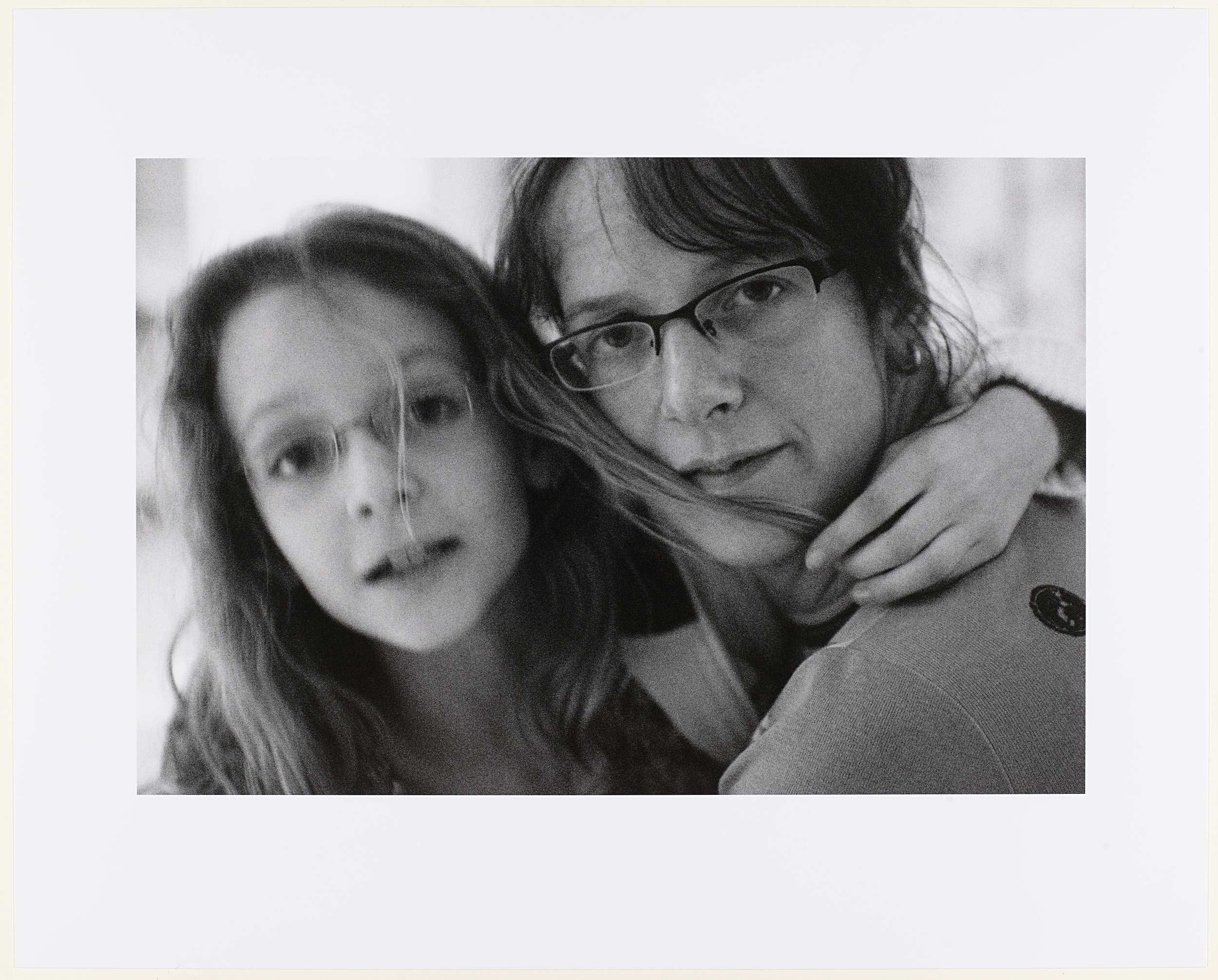

As the series develops, Lysanne is always bedfast, not moving, unconscious, not recovering (figs 9, 10, [11], 12, 13). She looks very vulnerable, especially as she seems unable to do more than just lie still. Her sister and mother, who are around in some of the photographs, are also unable to do anything about the child’s illness. There is a moving photograph of Melissa lying in bed with her sister, her arm around her (fig. 13). The series acquired by the Rijksmuseum ends with a portrait of Melissa and Margriet (fig. 14, Lysanne’s hands held by those of her sister, her mother and her father (fig. 15), and a close-up of Lysanne’s face after she passed away on 29 March 2008, as a result of a brain hemorrhage caused by the tumour (fig. 16). She was seven years and three months old. The last portrait was done exactly three months after Reinier van der Lingen started the series that seemed so innocent at first, but took such a cruel turn.

|

Fig. 10 Reinier van der Lingen, 25 March 2008. Inkjet print, 399 x 300 mm. Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv. no. RP-F-2009-89-10 |

|

Fig. 11 Reinier van der Lingen, 21 March 2008. Inkjet print, 268 x 400 mm. Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv. no. RP-F-2009-89-11 |

|

Fig. 12 Reinier van der Lingen, 26 March 2008. Inkjet print, 268 x 400 mm. Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv. no. RP-F-2009-89-12 |

|

Fig. 13 Reinier van der Lingen, 28 March 2008. Inkjet print, 267 x 399 mm. Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv. no. RP-F-2009-89-13 |

|

Fig. 14 Reinier van der Lingen, 25 March 2008. Inkjet print, 267 x 400 mm. Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv. no. RP-F-2009-89-14 |

‘… the story of loss …’

The moment Reinier van der Lingen first visited the hospital and learned how serious Lysanne’s condition was, he instinctively understood he simply had to have his camera at hand and continue making photos of his daughter. He therefore asked his parents to go to his home and fetch his camera. Until the very end, he documented Lysanne’s last days. It is remarkable how he succeeded in documenting the course of his youngest daughter’s hospital life. However shattered and powerless he must have felt at seeing his daughter slipping away, his photographs are never sentimental. They are not cool or distant either. Especially the close-ups reveal the parental love he naturally had. Van der Lingen took no recourse to standard tricks. The directness and frankness of his photographs make them even stronger, more shocking and moving. Because everything that took place in the hospital is followed from close at hand, nothing is held back from the viewer. In an impressive and honest manner, the series therefore reveals what it must be like to suddenly lose a child, even if it is impossible for anyone who never went through such a heartbreaking experience to fully identify himself with what the photographer must have endured.

Knowing that the photographer was the young girl’s father, one can easily empathize in the story as it is told in the photographs that constitute 3 Months. In a rare and penetrating way the series pictures show what suddenly took place in a young family’s home life after it was established that something was grievously wrong with one of the children.

As Audrey Linkman makes clear in her recently published book Photography and Death, at some point in the 20th century it became a taboo in our part of the world to make portraits of people after they have passed away.[1] And even if there is a revival – no pun intended – of postmortem portraiture of infants, as Linkman concludes, ‘photographers are advised to avoid focusing on pain and despair. Instead, through lighting and the display of emotion, they should attempt to capture the relationships that tell the story of loss in an appropriate and sensitive way. They should therefore avoid – when possible – photographing the infant when surrounded by tubes in an incubator.’[2] Even if this applies first and foremost to newborns, whereas Lysanne van der Lingen was seven at the time she was hospitalized and passed away, Linkman’s observation suggests that Lysanne’s father’s series is the more impressive and courageous.

3 Months is remarkable for yet another reason. In her Photography and Death Linkman mentions many photographs and photographic series concerning death, all of which were made or begun after the people portrayed had already passed away or were diagnosed with an illness that would ultimately lead to their death.[3] The only series in her book in which the person portrayed died unexpectedly is Ishiuchi Miyako’s Mother’s 2000-2005. Traces of the Future (2005). Miyako’s mother was, however, already an old woman, and the series was started only after the photographer’s father had already died – which means that Miyako’s mother’s death was bound to come about within a foreseeable period, and that the photographer was already aware how much was at stake. Reinier van der Lingen, on the other hand, was of course in no way whatsoever prepared to lose his daughter at such a tender age.

A cruel turn as witnessed in Reinier van der Lingen’s series – from untroubled happiness to utter distress in just three months time – seems to have been very rarely depicted through photographs. This makes his series even more remarkable. Although photographs of children have been made in large quantities ever since photography was invented, not much seems to have written on them in relation to death, illness, violence and pain. In order to fully realize how exceptional the series indeed is and to establish how Reinier van der Lingen’s series 3 Months deviates from the way children have usually been photographed, we shall now give a brief sketch of the tradition of photographs of children.

A New Art, A New Tradition

Soon after photography was introduced in 1839, portraits became an important subject. They have remained so ever since. Since early photographers often sought subjects that were close at hand, it will come as no surprise that when making portraits they often decided to photograph their own offspring. William Henry Fox Talbot (1800-1877) is just one early example (fig. 17).[4] Many later examples can be mentioned as well, including Heinrich Kühn, Edward Weston and Sally Mann. The Rijksmuseum recently acquired an intimate scene that Swiss-American photographer Robert Frank (b. 1924) made of his son Pablo, who is barely visible behind a table and flowers (fig. 18).

|

Fig. 17 William Henry Fox Talbot, Portrait of Rosamond Constance Fox Talbot, the photographer’s daughter, c. 1842. Salted paper print, 113 x 95 mm. Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv. no. RP-F-F17637 |

It is difficult to establish when photographing one’s own children became a genre in its own right that was practiced on a large scale. The amateur Eduard Isaac Asser (1809-1894) – who was a lawyer by profession – may well have been the very first in The Netherlands who often portrayed his children and other relatives (fig. 19). Most of these portraits are made in the 1840s and 1850s.[5]

|

Fig. 19 Eduard Isaac Asser, Portrait of Charlotte Asser, the photographer’s daughter, c. 1842. Daguerreotype, 81 x 70 mm. Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv. no. RP-F-AB12282 |

The steep rise of the number of amateur photographers since the 1890s was undoubtedly an important stimulant to the genre of lovingly depicted children.[6] The extensive series the Dutch amateur photographer Hendrik Teding van Berkhout (1879-1969) made of his family life after his marriage in 1908 is a case in point. His wife and two daughters, who were born in 1909 and 1910, respectively, were his main subjects during the many years Teding van Berkhout used his camera. The resulting photographs chronicle the life of a family that seems to have been sheltered from shocking events. When his youngest daughter fell through the netting of her cradle one day, Hendrik Teding van Berkhout reportedly hurried home from his nearby office to capture the incident (fig. 20).[7]

It seems to have taken quite some time before professional photographers began making their family life a subject in its own right as well. In The Netherlands, photographers like Ed van der Elsken (1925-1990) and Kors van Bennekom (b. 1933) often took their children as a subject. The latter even specialized in it. His book De familie van Bennekom (The Van Bennekom Family, Amsterdam 1990) is a loving testament to his family life since 1952, when he first met his future wife Ine.[8]

Sheer happiness

One of the best-known portraits of a young child is the one Alfred Stieglitz (1864-1946) made of his daughter Katherine in 1905, when she was seven years old (fig. 21). It has been often reproduced, for instance in the 12th issue of Camera Work (October 1905). In the exhibition catalogue Priceless Children. American Photographs 1890-1925 (2001-02) this portrait was contrasted to the photographs Lewis Hine started making of child workers around the same time. Of course, Hine’s well-known photographs served a very different purpose (fig. 22). George Dimock therefore wrote, ‘By way of contrast, the Pictorialists excelled in the portraiture of children, often their own, whose full subjectivity was an inherent aspect of their pricelessness.’[9] Indeed, many a sweet soft focus portrait can be found among the photographs made by Pictorialists around 1900 (fig. 23).

|

Fig. 21 Alfred Stieglitz, Portrait of Katherine Stieglitz, the photographer’s daughter, 1905. Photogravure, 207 x 169 mm. Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv. no. RP-F-F17653 |

|

Fig. 23 Louis Fleckenstein, Mother Breast-feeding her Baby, c. 1900. Platinum print, 301 x 251 mm. Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv. no. RP-F-F17652 |

Ever since amateurs and Pictorialists created the tradition of lovingly depicting children, it has been common use to choose happy moments before anything else. Suppliers of cameras, photographic plates and papers and other necessities have continuously stressed the importance of capturing the happy side of family life. Many advertisements by firms such as Kodak can illustrate this point well. It is only logical that Kodak and other firms emphasized the desirability of recording sunny moments in their customer’s lives. The darker sides of children’s or family lives are nearly absent in photographs made by professionals or serious amateurs. Happiness prevails, or so it seems.

Postmortem photography

With regard to the inclination to preserve happy moments above all else, we should of course not pass over the existence of postmortem photographs. These were frequently made both of children and adults from the early days of photography until somewhere in the first quarter of the twentieth century.[10] They were, however, most often made by professional photographers who were not related to the deceased person, and thus not emotionally involved. The result can, however, be touching, as is the case of six-year-old May Twiss. Her postmortem portrait is part of a book printed in 1866 by the Utrecht firm Kemink, but undoubtedly commissioned by May’s parents (fig. 24).[11] The book is simply titled May. 13 Jan. 1859 † 30 Mey 1865 and consists of 199 pages full of pieces of text derived from the Bible and quoted from poets like Alfred Lord Tennyson and Henry Longfellow. These texts are witness to the parents’ wish to find consolation and their efforts to cope with their loss: they all speak of trust in God, keeping the memory of May alive, disaster, affection, resignation, bereavement, etc.[12]

Two extremes

The happy moments that are so often cherished by way of photography on the one hand, and the sad postmortem photographs on the other, are two extremes. These two genres seem to be mutually exclusive. Moreover, there seems to have been very little captured between these two poles, photographically speaking. Most of the time we see either unclouded pictures of happy children (and their parents) or portraits made only after death had already ended a young child’s life. To be sure, this gap does not exist because there was never anything in between unclouded happiness and irrevocable death; on the contrary. Indeed, it is known, for instance, that Katherine Stieglitz, whose dreamy portrait was mentioned above, had an uneasy relationship with her father. She never accepted her parents’ divorce and her father’s relationship with Georgia O’Keeffe. After she gave birth to a son in 1923, Katherine suffered from what was called ‘post partum dementia praecox’ and was institutionalized for the rest of her life.[13] The same contrast between the happiness suggested by a well-known photograph and subsequent events is to be found with Stieglitz’s contemporary Gertrude Käsebier’s Blessed Art Thou among Women from 1899. A young girl in black and a woman in white are standing in a doorway, the woman bending over and laying her arm on the girl’s shoulder. Soon after the photograph was made, the young girl, Peggy Lee, died of childhood diabetes, a blow that wrecked her parents’ marriage.[14]

In both cases the sad course of events could not have been anticipated by the photographers (Stieglitz and Käsebier), but it is significant that these two photographs, invariably regarded and understood as lovely images of children (and parental love), have such a sad – and rarely told – background. These two pictures fit perfectly in the tradition that young children are either portrayed in an intimate, casual and informal way that shows nothing of any eventual unhappiness, or when nothing else could be done other than capturing a last look. Most publications on childhood and photography, including Audrey Linkman’s Photography and Death (2011) and Anne Higonnet’s Pictures of Innocence (1998), seem to pay little attention to the subject of illness and the way that is dealt with photographically.[15]

‘Hard news’ photography

The tradition of photographing children only when all is (still) well or after death has already mercilessly struck applies particularly to photographs made by or for parents and other relatives of the children involved. The large area between these poles is only present extensively in photographs that depict the distress of other people’s children. Thus war, violence, accidents and natural disasters have often resulted in heart-breaking photographs featuring children. Nick Ut’s picture of nine-year old Phan Thi Kim Phúc and W. Eugene Smith’s pietà-like photograph of Tomoko Uemura in her Bath are just two famous – or notorious – examples, both made in 1972. The first shows a girl who – stripped of her clothes – is running away together with her brothers and cousins after a South Vietnamese napalm attack during the Vietnam War. The latter shows a Japanese girl who was infected with what is called Minamata disease.[16]

When Smith visited Japan in 1971 for an exhibition of his work, he heard about the inhabitants of the fishing village of Minamata, who had been struck by a mysterious illness. After some time it became clear that water pollution from a local factory over some thirty-five years was the cause of the mental and physical disabilities and many early deaths. The mercury that had been dumped by the factory had become part of the food chain, and through this in the end affected human beings as well. The neurological disease is now known as Chisso-Minamata-disease – named after both the factory and the village.

Smith followed the villagers’ struggle for recognition for four years, during which the Chisso company only reluctantly gave in. After having published his Minamata photographs in several magazines, Smith made a book of them in cooperation with his American-Japanese wife Aileen Mioko in 1975. It was simply called Minamata. The book tries to show in both words and pictures how the local population was struck, how they decided to take action against the company, how little success they had at first, but how they won the case in the end. By then, Smith and Mioko’s book had already been published.[17]

The best known photograph from the series is Tomoko Uemura in her Bath, lying in her mother’s arms and fully dependent on her. In 1997, twenty years after the girl died, her family requested that this photograph would never be published again. The Rijksmuseum acquired another photograph of the same girl a few years ago (fig. 25): Smith’s series on Minamata is one of the classic examples of how photographs moved magazine readers comfortably sitting in their chairs at the other side of the world, and helped to influence the course of history.[18]

It is understandable that Tomoko Uemura’s family wished the photograph not be published again (and again and again), however honest, moving and influential it had been. The case against Chisso had been won, but the girl was affected and dead nevertheless. Nothing could change that, and it must indeed have been painful to be confronted by the photo so often, even if the girl’s mother had agreed to posing for Smith for this picture.

On the other hand, Nick Ut’s 1972 photo of Phan Thi Kim Phúc would never have been published had it not been for Horst Faas, picure editor at Ut’s agency Associated Press (AP) and a photographer himself (twice winning the Pulitzer Prize). Faas is known to have insisted upon publishing the photo after an editor at AP had objected because of the girl’s nudity. ‘Pictures of nudes of all ages and sexes, and especially frontal views were an absolute no-no at the Associated Press in 1972,’ Faas wrote later.[19] After the photo was indeed published worldwide it won Ut both the Pulitzer Prize for Photography and the World Press Photo Award in 1972. The photo is one of the most shocking and memorable pictures ever published, and became a symbol of the Vietnam War. As Gisèle Freund wrote in her book Photographie et société (1974), Life published it alongside a more hopeful colour photo of the same girl, on which she is depicted smiling after having been in a Saigon hospital for fifteen weeks to undergo skin grafts and physical therapy.[20]

Nick Ut is not the only one who has won the World Press Photo award with a picture involving children. On the contrary, quite a few World Press Photo awards have been given to pictures depicting either children or adults mourning over the loss of a child. Frank Fournier’s photo of twelve-year-old Omaira Sanchez, who was trapped after the eruption of a volcano in Colombia, is just one example. While still alive when the photograph that won Fournier the award in 1985 was made, the girl died sixty hours later of a heart attack, rescuers having been unable to free her from the debris. Since 1972, sixteen other prize-winning photographs have involved children as well, i.e., some forty percent. That high percentage may indicate that photographs showing children in gruesome situations readily evoke feelings of compassion, horror, and protest. This propensity may be referred to as the ‘Anne Frank effect’, i.e., the effect that young persons involved in something horrible will more easily become the symbol of injustice or barbaric and criminal acts than adults will. Seen this way, Tomoko Uemura and Phan Thi Kim Phúc share the same sad fate as Anne Frank, the Jewish girl who died in the Auschwitz concentration camp in 1944, age fifteen, after having been deported from Amsterdam. Her diary was published posthumously and has become one of the most powerful symbols and representatives of the six million Holocaust victims.[21]

That human suffering often appears in ‘hard news photographs’ is a sad inevitability. Illness, death, and injuries are not absent in more personally orientated photography, either. However, most often it is adults who we see (either the photographer or his/her relatives and close friends). The best-known example is perhaps the American photographer Nan Goldin (b. 1953). In 1982, she published her now famous book The Ballad of Sexual Dependency, which introduces us to the photographer’s circle of family and friends. One of the most famous photographs from the book is Goldin’s self-portrait after having been battered by her boyfriend (1984), in which we see that both her eyes are still swollen.

Goldin is not the only adult who appears in photographs in a far from flattering way, such as – in her case – after having been beaten. Children are much less often the subject in this kind of photography. As has been stated earlier in this essay, they have most often been photographed when all was well or after death had occurred. The probably best-known photograph of a sick child – Henry Peach Robinson’s 1858 Fading Away, showing a young girl in bed dying of consumption – is a ‘set-up’, a composite print made from five carefully staged negatives, and does not show a real ill child.[22]

Immortal

According to Reinier van der Lingen himself, he realized immediately that he wanted to tell the story of losing his youngest daughter. Soon after she passed away, he started making selections from his most recent photographs and began composing 3 Months. Had he been a writer, he would have written a book. Being a photographer, it was through this medium that he showed to the world what had happened to him so unexpectedly. As Audrey Linkman stated in Photography and Death, photographs can be used to let other people know and understand what is otherwise seldom communicated in words.[23] After all, people often find it difficult to talk straightforwardly about someone else’s loss. Losing a child is however a thing too big to be kept silent. It is therefore perfectly understandable that someone going through such an immense grief feels the need to express it, be it through photographs or otherwise. Reinier van der Lingen wanted it to be known that he once had a perfectly happy family – a perfectly average one, too –, and that this is what happened to him, and that this is how he experienced it. Moreover, by publishing a book on his daughter Lysanne, Van der Lingen felt she would be immortalized in some way. By making the photographs public, she will never again die.[24]

—

Reinier van der Lingen’s privately published book 3 maanden can be ordered by contacting the photographer. See his website www.reiniervanderlingen.nl. On that same website his series ‘Family Life’ and ‘Hospital Life’ can be seen as well.

Notes

1. Linkman 2011, pp. 75-80. ↑

2. Linkman 2011, pp. 80, 85-86 (quote taken from p. 85). ↑

3. See especially chapter 3 of her book. ↑

4. Among the many books on Talbot, one of the best is Schaaf 2000. ↑

6. For an overview of children’s photography see for instance Higonnet 1998. Cf. Holland 2004.↑

7. Rooseboom 2002. Teding van Berkhout’s photographs are part of both the Rijksmuseum and Spaarnestad Photo/Nationaal Archief collections. ↑

8. Bennekom 1990. ↑

9. Dimock 2001-02, p. 15. ↑

10. On postmortem photography see: Burns 1990, Ruby 1995, and Linkman 2011. On Dutch postmortem images see: Sliggers 1998, to which Anja Krabben contributed an essay on Dutch postmortem photographs. ↑

11. Krabben 1998, p. 165. ↑

12. May. 13 Jan. 1859 † 30 Mey 1865, Utrecht 1866. The only copy known to me is in the Rijksmuseum library. ↑

13. Dimock 2001-02, p. 16, based on Lowe 1983, pp. 248-49. ↑

14. Dimock 2001-02, pp. 16-17. ↑

15. Linkman 2011, Higonnet 1998. ↑

16. Nick Ut’s photo was distributed by his agency Associated Press (AP) and has frequently been published ever since. Smith’s picture was first published in Life in 1972 [check]. ↑

17. Smith/Smith 1975. ↑

18. Life 23 June 1972, ‘Letters to the Editor’. ↑

19. Faas/Fulton (accessed May 25, 2011). ↑

20. Freund 1974, p. 203; Life 29 December 1972, pp. 54-55. ↑

21. Frank 1947. It has since been translated into more than sixty languages. ↑

22. The photographic is in the collection of the Royal Photographic Society. ↑

23. Linkman 2011, pp. 83-85. ↑

24. Email of Reinier van der Lingen to the author, 2011. ↑

Literature references

Bennekom, Kors van, De familie van Bennekom, Amsterdam 1990.

Boom, Mattie, Eduard Isaac Asser (1809-1894), Amsterdam s.a. [1998].

Burns, Stanley B., Sleeping Beauty: Memorial photography in America, Altadena, CA, 1990.

Dimock, George, ‘Priceless Children: Child Labour and the Pictorialist Ideal’, in Priceless Children: American Photographs 1890-1925, Greensboro/Santa Barbara/New York 2001-02.

Faas, Horst, and Marianne Fulton, ‘How the Picture Reached the World’, http://digitaljournalist.org/issue0008/ng4.htm.

Frank, Anne, Het Achterhuis. Dagboekbrieven van 14 juni 1942-1 augustus 1944, Amsterdam 1947.

Freund, Gisèle, Photographie et société, s.l. 1974.

Higonnet, Anne, Pictures of Innocence: The history and crisis of ideal childhood, London 1998.

Holland, Patricia, ‘“Sweet it is to scan …” Personal photographs and popular photography’, Liz Wells (ed.), Photography: A critical introduction, London/New York (Routledge) 2004, pp. 113-158.

Krabben, Anja, ‘Onveranderlijk de eeuwigheid in’, in B.C. Sliggers ([ed.]), Naar het lijk. Het Nederlandse doodsportret, 1500-heden, Haarlem 1998, pp. xx-xx.

Linkman, Audrey, Photography and Death, London 2011.

Lowe, Sue Davidson, Stieglitz. A memoir/biography, New York 1983, pp. 248-49.

Rooseboom, Hans, ‘Hendrik Teding van Berkhout’, in Wim van Sinderen (ed.), Fotografen in Nederland. Een anthologie 1852/2002, Ghent-The Hague 2002, pp. 376-77.

Ruby, Jay, Secure the Shadow: Death and Photography in America, Cambridge, MA/London 1995.

Schaaf, Larry J., The Photographic Art of William Henry Fox Talbot, Princeton, NJ, 2000.

Sliggers, B.C. (ed.), Naar het lijk. Het Nederlandse doodsportret, 1500-heden, Haarlem 1998.

Smith, W. Eugene, and Aileen M. Smith, Minamata, New York 1975.