Erwin Olaf: The Siege and Relief of Leiden

History painting remediated into history photographyMaartje van den Heuvel

Extract

This article deals with the recently produced series The Siege and Relief of Leiden by Dutch photographer Erwin Olaf, a commission of Leiden University and Leiden’s municipal Museum De Lakenhal. This series of a monumental history piece, six figure pieces and two still lifes deals with an important event in the history of The Netherlands: the siege of Leiden by the army of Spain’s Philip II, and the relief of the city by the rebellious Dutch ‘Sea Beggars’ on 3 October 1574. The author examines how this series adds to a centuries-old tradition of history paintings on the same subject and how it forms a new step in the development of Erwin Olaf’s oeuvre. The series is representative of a trend in which lens-based media (photography and video art) explicitly refer to compositions and iconographic formulae that are known from painting. Erwin Olaf’s series is compared with work by Andreas Gursky, Jeff Wall and Bill Viola. The author finds that the series by Olaf is more in situ, functioning more purely for the commemoration of historic events, as history painting used to do. She introduces the term ‘history photography’ for this case of remediation of a tradition of painting into photography.

Through the spring and summer of 2011, the Dutch photographer Erwin Olaf (b. 1959) worked on a monumental history piece and a series of related figure pieces, portraits and still lifes about a key event in Dutch history, the relief of Leiden on 3 October 1574. In this series Olaf adds to a tradition of paintings on this subject which began just after the event took place. After a brief description of the historic events of the relief of Leiden, this article will explore the different artistic traditions and developments which come together in this series, the artist’s way of working, and his specific addition to these previous histories. Finally, the series will be positioned in the context of contemporary art production, in which today’s lens-based media photography and video art explicitly refer to visual formulae that were developed in the history of painting. I will argue that this series by Erwin Olaf can be seen as a fully fledged implementation of the remediation of the old tradition of history painting into a renewed genre, which I will introduce here as ‘history photography’.

1574: the siege and relief of Leiden

Like most other countries and peoples, the Dutch have some key events in their struggle for independence that are still commemorated today. The relief of Leiden is one of them. This was the moment they broke loose from the harsh rule by the greatest power in Europe of the 16 th century, Spain, under Philip II. In response to rebellious tendencies in the Netherlands, the Spanish undertook measures to keep the Dutch in line. Troops under the command of the Spanish general Francisco de Valdés surrounded and besieged Leiden in May 1574, in an effort to force the population into submission by starving them out.[1] The famine and ensuing plague brought on by the action caused suffering and death within the city walls, finally almost reducing the population of Leiden from 6000 to 3000. In messages sent into the city by carrier pigeons, the leader of the Dutch rebellions, William of Orange (Willem van Oranje), the ancestor of today’s Dutch royal house, encouraged the citizens to hold out. In a legendary dramatic scene – which probably never really occurred – the mayor of Leiden at one point offered his arm to the hungry citizens, symbolically suggesting that they eat his body first, before surrendering. It only added to Dutch pride that when the relief of Leiden was finally accomplished, it came by a naval action, typical for this land which lies largely below sea level. The ‘Sea Beggars’ (a derisory nickname, which the Dutch rebels proudly adopted for themselves) caused flooding by breaking the dikes, setting the area around Leiden under water, and sailing in to the occupied city on boats.[2]

Although there were other sieges and relief actions at Dutch and Flemish cities in the same period, it is especially the relief of Leiden that is commemorated on a large scale: after the Queen’s Birthday and Carnival, it is the third large public celebration in The Netherlands. It is considered important because it not only achieved liberation and autonomy for the Dutch, but in the end also led to the founding of their own state and cultural identity. It saw the liberation of the Protestant Dutch from oppression by Catholic Spain. As a reward for the city’s loyalty, and to promote Dutch intellectual life, the new leader, William of Orange, founded the first Dutch university in Leiden in 1575.[3] The events in Leiden marked the beginning of a period of flourishing of the economy, culture and science in The Netherlands: the 17 th century, which is still known as the Dutch Golden Age.

the artistic tradition

The tradition of history paintings commemorating the events of the relief of Leiden started in the year of the event itself. Dutch painter Otto van Veen painted the moment of liberation, when the Sea Beggars sailed their boats into the city and distributed white bread and herring. (fig. 1) The rebels are carrying the double orange-white-blue flag, which was the flag of the Orangeists, those who sided with the ‘Prince of Orange’. It was the precursor of today’s Dutch red-white-blue flag, and also recurs in the 2011 photo work Erwin Olaf made on Leiden’s relief.[4]

|

Fig. 1 Otto van Veen (1557–1602), Distribution of Herring and White Bread by the ‘Sea Beggars’ at the relief of Leiden, oil on panel, 40 x 59,5 cm, 1574, collection Rijksmuseum Amsterdam. |

The differing historical contexts influenced the iconography of the paintings through the centuries, thus communicating messages of historical awareness that were appropriate to their time.[5] Most paintings had a positive, idealizing tenor. The 16 th and 17 th century paintings often show the euphoric moment when the liberators, the Sea Beggars, entered the city, and the distribution of the first food after the long period of hunger. In the 19 th century, an era in which nationalistic sentiments and a renewed interest in the country’s past emerged in The Netherlands, several history paintings of the events in Leiden were again made. Two of them were in possession of the Dutch Royal House: King William I bought one in 1816 by the painter Mattheus Ignatius van Bree, and William II acquired one in 1829 by the painter Gustaaf Wappers, respectively. (fig. 2) In these paintings the virtuous offering of his body by the mayor, Pieter Adriaansz. Van der Werf, was central, with its message to the viewer about ultimate loyalty to the rebels’ leader William of Orange – the ancestor of the commissioning monarchs.

Noblesse of virtue, in this case piety, remained central in another 19 th century painting. Henricus Engelbertus Reyntjens painted the moment at which city administrator Jacob van der Does sat praying at the side of his younger cousin, Jan van der Does, also administrator of Leiden, when he is surprised by the Sea Beggars entering Leiden on their boats.[6] (fig. 3) This motif of Jacob van der Does seeing the liberators arrive was cited again by photographer Erwin Olaf in his 2011 depiction of the story.

the commission

Erwin Olaf’s series about the relief of Leiden was commissioned by Leiden University and the municipal Museum De Lakenhal.[7] Museum De Lakenhal contributed original objects from Leiden’s history and specialist knowledge and curatorship for contemporary art related to the city of Leiden. Also, it has in its collection several of the history paintings on the relief of Leiden which formed the tradition to which Erwin Olaf was to add as a photographer. Leiden University was involved because of its specialism in photography research, centred in the Special Collections department around its museological photography collection.[8] Furthermore, at its Research Institute for History, a research programme entitled Tales of the Revolt: Memory, Oblivion and Identity in the Low Countries, 1566-1700 was ongoing during the time of Olaf’s commission.[9] New knowledge and visions of the events of 3 October 1574 that were developed in this programme were introduced to Erwin Olaf as well, who processed them in his 21 st century version of the representation of the story.

The name of Erwin Olaf as the appropriate artist to carry out this commission was mentioned by the two commissioning institutions independently, and he was the only artist approached for it. His skills and artistry in the field of staged photography were well-known, and he had experience and skills in making photography based on paintings.[10] Furthermore, Olaf’s work as a photographer cannot be seen apart from his public appearances, in which he always made a case for social tolerance, gay rights, and what he calls sexual and racial diversity. The ‘Black Tea Party’ he organized in a popular club in Amsterdam, where the mayor of Amsterdam at the time also appeared as a spectator to symbolically support the event, is a significant example of this. All these aspects made the choice of Erwin Olaf for this commission regarding an archetypal liberation, in the tradition of history painting, an appropriate one.

title

development in the oeuvre of Erwin Olaf

The challenge to the artist to make a history painting and a series of figure pieces and still lifes of a complex historical subject, seems to mark an interesting next step in Olaf’s oeuvre. Initially a photojournalist, in the 1980s he developed his interest in staged photography, or photography of the imagined, as he called it.[11] As was clear from earlier work like Chess Men (1988/1989, fig. 5) and Mind of their Own (1995), the photographer likes having all kinds of people as his models: black, white, pregnant, fat, thin, mutilated or dwarves, in sometimes extreme, sexual poses. This was inspired by a desire to freely include all extremes of human appearances in his work, providing all sorts of people with their moment in the sun, and an opportunity for public performance. Thus, Olaf’s Relief of Leiden contains a black man, a woman with Down’s syndrome and a dwarf, although no historic source compelled this.

|

Fig. 5 Erwin Olaf, Chessmen V, from his series Chessmen, 1988-1989, gelatin silver print, .. x .. cm, collection |

The sometimes abundant theatricality and extravagance of his early work slowly made way for the more introvert series Rain (2004), Fall (2008) and Grief (2007). Here he worked out the formula of the film still, not only controlling suggestions of stories and emotions, but also playing with the suggestion of a certain historical period, in this case America of the 1950s. In 2009 he did this again with historical Russian and Black middle-class American environments, in the almost monochrome Dusk and Dawn. This historicizing way of working can also be seen as run-up to the 2011 Leiden commission.

Erwin Olaf’s interest in historical fine art has been clear since his adoption of the classical rosette shape around his pictures in the series Blacks (1990). The specific preoccupation with Renaissance painting came in 2008, when he reproduced historical paintings by Spanish masters like Murillo and Velázquez in the series Laboral Escana Gijon for the Spanish city of Gijon.[12] (fig. 6) Olaf became intrigued by the expressive power achieved in painting by the sober means of lighting figures in a dark environment by one single light source. The expression of meanings by compositions, poses, gestures and attributes also caught his interest. In commercial commissions for BSI Bank, Moooi Design and the fashion trademark People of the Labyrinths, with great subtlety he revived compositions from historical Dutch Renaissance paintings, including still lifes and portraits. (fig. 7)

preparations

For the 2011 commission Erwin Olaf was asked to make a monumental history piece on the events of Leiden’s relief, which would be permanently shown in the galleries of Museum De Lakenhal, alongside historical paintings with the same motif. In addition, he was asked to make a series of smaller photographs of the history piece, as well as a series of derived figure pieces, portraits and still lifes that were to be shown in the exhibition space of the Leiden University Library, and would be designated for the Special Collections’ photography collection there.

Although he looked to the pictorial tradition on this subject, and details sometimes subtly link back to paintings, unlike in the Gijon commission there were no specific images that served as direct examples to copy. The all-over compositions, the ordering of the figures and the working out of the details were all inventions by Erwin Olaf himself.

The Pieterskerk (St. Peter’s Church) in the centre of Leiden served as a studio – and an appropriate one. This building, which was built over the long period from 1121 to 1570, was already in the heart of Leiden at the time of the siege and relief. In his first visit of the church Olaf chose the camera position, so that the spiral staircase of the pulpit formed the right border of the composition, whereas in the far left corner the doors of the church were to be seen. Olaf would have the liberators enter through these – just as in the 19 th century painting by Reyntjens. (fig. 3) For this occasion, Olaf could make use of historical objects from the collection of The Lakenhal, that normally are displayed for the commemoration of the history of the city’s relief. These included examples of the tiny notes that the Sea Beggars sent by pigeon to the suffering Leiden citizens, and a hotchpotch kettle – famous in Holland – which was found in the Spanish camp, marking the triumphal moment of discovery that the Spanish soldiers had indeed fled.

Olaf introduced several changes that would make his photographed imagery differ from the historic tradition. (fig. 11) First, the project Tales of the Revolt at Leiden University had indicated that the role of mayor Van der Werf, which was so virtuously depicted in 19 th century history paintings, was not that prominent after all.[13] Together with other figures who sought to negotiate with the Spanish, he was called a ‘dove’ for his gentle approach. Other actors in the events, like the city’s secretary Jan van Hout, the commanding officer Jan van der Does, and his cousin Jacob van der Does, took a harder line. They were called the ‘hawks’, and their actions are now considered to be of larger importance than the mayor’s. Olaf gave these hawks a more prominent role in his photo works. A morbid picture emerges of Leiden’s leaders threatening their own citizens with death, should the people weaken in their resolve to stand just as firm as as the Spanish opponent, and consider surrender. Hence the gallows that Olaf introduces in the scene.

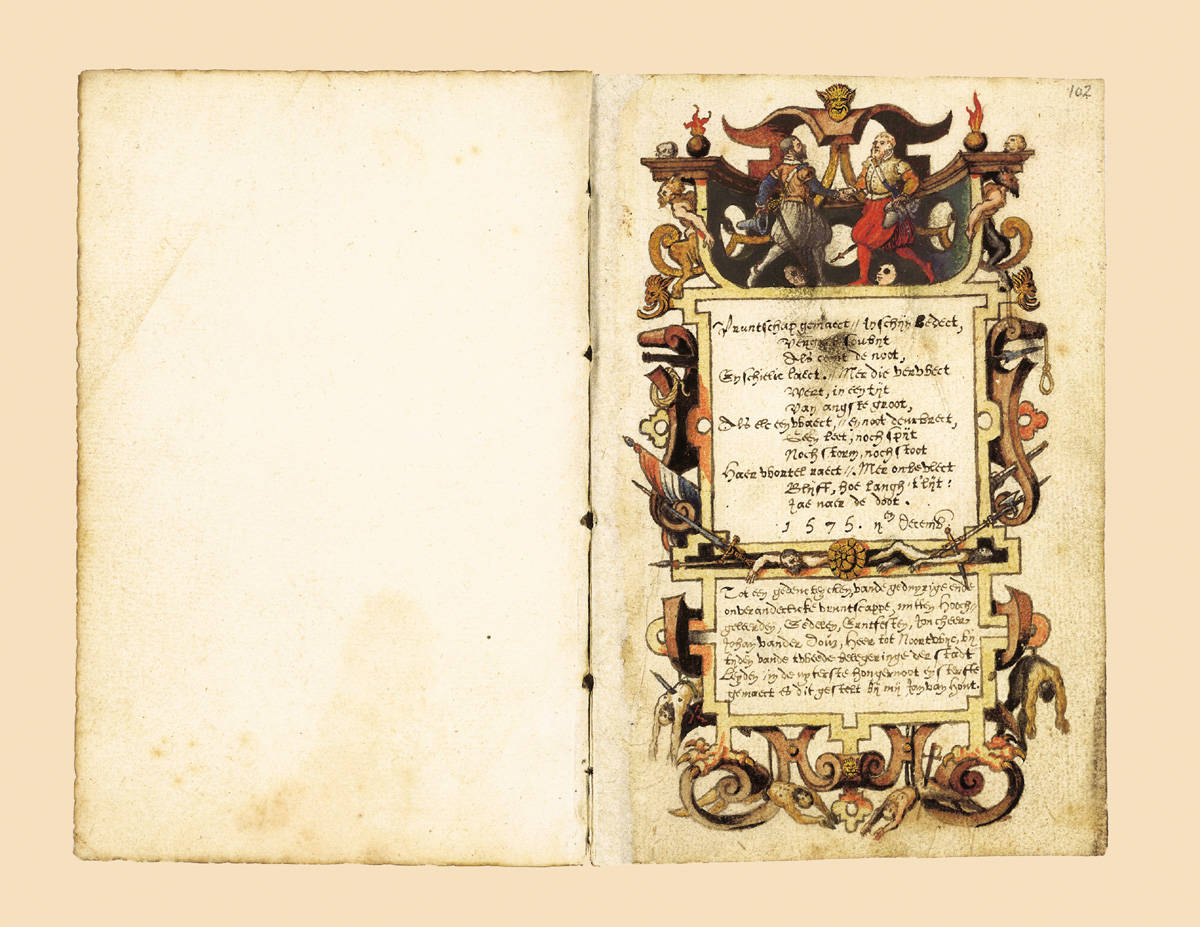

Where the history paintings of past centuries had given the figures depicted positive connotations like ‘liberation’ and ‘virtue’, Olaf clearly chose the darker side of the story. ‘In old paintings, events were often depicted in a softened way,’ he said, ‘Thanks to photojournalism, we now know what war looks like and how emaciated people in concentration camps were. This harshness is in my photographs as well.’[14] Interestingly enough, by introducing this harshness, Olaf connects to a very early depiction of the reality of the relief of Leiden. In 1575, in the Album Amicorum of his colleague Jan van der Does, the ‘hawk’ Jan van Hout drew himself and his friend triumphantly shaking hands above a bloody ensemble of impaled corpses and a gallow. (fig. 8) The harshness of Olaf’s depiction of the Leiden relief connects surprisingly well with the way these men at the time perceived the event.

Furthermore, Olaf chose to put more emphasis on the plague, instead of the famine. The team who assisted him turned to academic hospitals to learn about the exact physical symptoms of the victims of the specific kind of plague that was abroad in Leiden in those days. But it also allowed Olaf to introduce the dramatic-looking figures of the plague doctors with their beak-like masks that contained herbs that would prevent them from catching the plague themselves.

Another change that Olaf made was introducing a prominent role for two women and a black man into the parade of white male figures that had dominated the verbal and visual narrative of the Leiden relief in preceding centuries. Magdalena Moons, a Dutch woman who was engaged to Francisco de Valdés, had been important because she persuaded this Spanish commander to postpone the attack of Leiden. While she was depicted before in figure pieces where she was stopping her fiancée from approaching the town of Leiden, Olaf is the first to give her an individual monumental portrait as a leading character. The second woman is a mythical figure, the goddess Minerva (Pallas Athene). Being the goddess of both war and wisdom, in historical iconography she was the emblematic figure who referred to both the struggle that had been won, as well as to the intellectual richness that came when William of Orange founded the first university in Leiden. Both meanings are included in the emblem of Leiden University, where Minerva is to be seen with weapons at her feet and a book in her hands. (fig. 9) Olaf depicted her in a militant way in his history piece, in the way allegorical figures used to be mixed among realistic ones in historical painting. In the individual portrait Olaf depicted Minerva in the allegorical formula as goddess of wisdom, as in the university’s old seal and contemporary logo.

The black merchant, both in the history piece and in a portrait, was another invention by Olaf. When he asked if it were possible that black people had been in the city at that time, an early 16 th century painting by Jan Mostaert was located in the Rijksmuseum. (fig. 10) Although there would have been very few black people walking around in The Netherlands in those days, if this was the case, they would have been wealthy merchants or high-rank representatives of one of the African kingdoms with which there was contact in international diplomacy and trade.

|

Fig. 10 Jan Janz. Mostaert (circa 1483-1555/56),Portrait of an African man, circa 1525-1530, oil on panel, 31 x 21 cm, collection Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam. This painting served as a direct inspiration for Olaf’s Merchant (fig. 15). |

production

According to Olaf, this project was of the largest scale in which he had ever worked, in terms of numbers of crew members, models, histories, previous images, ideas and opinions involved.[15] Professional models were combined with citizens of Leiden, who were cast after a call in the local newspaper.[16] For the leading actors he generally chose professional models.[17]

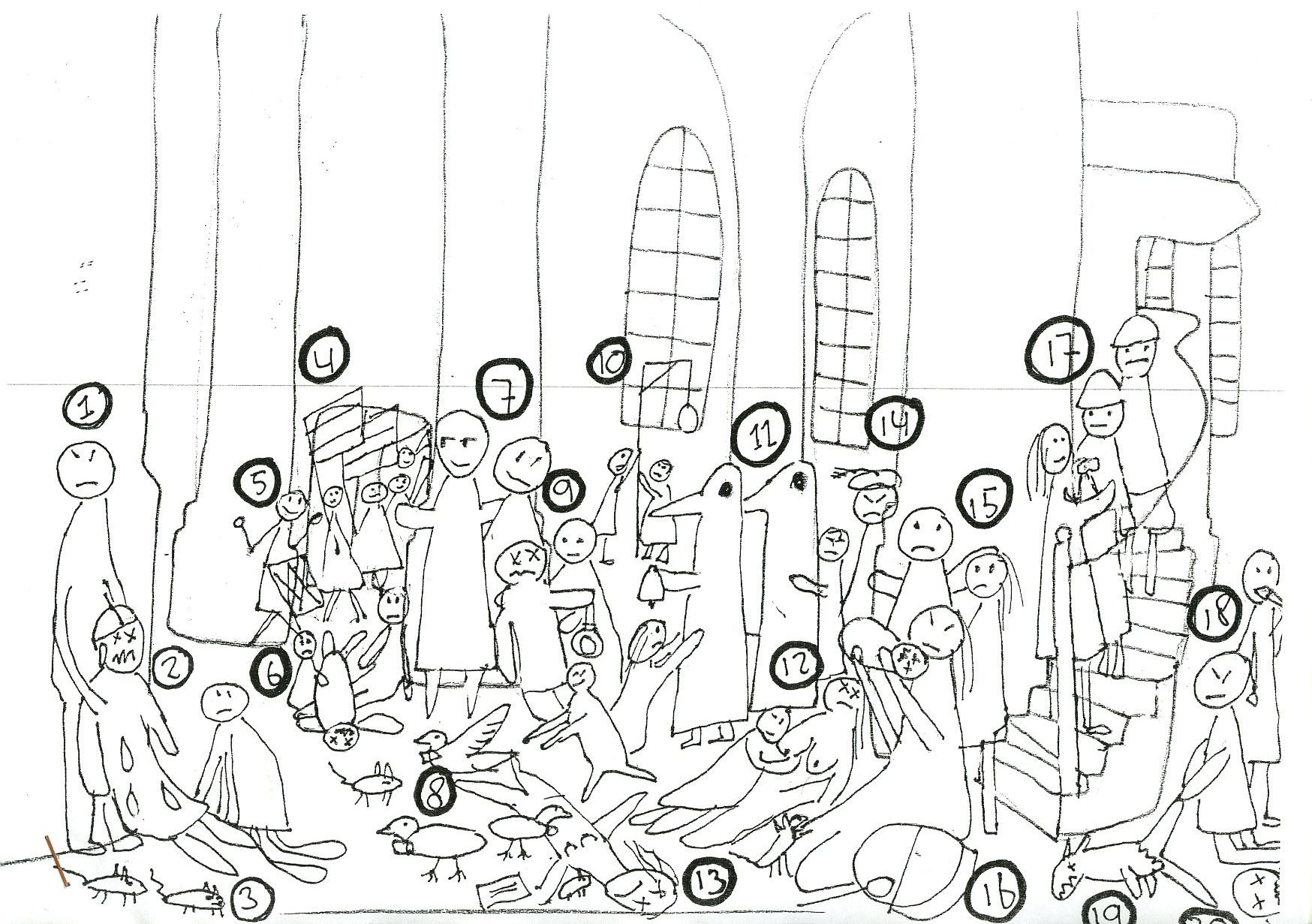

As a preparation, a day before the actual photo shoot, Olaf made a trial shot of the history piece with stand-in models, members of the Leiden amateur photographers club. (fig. 12) The actual photo shoot took place with a disciplines schedule over three days: 6, 7 and 8 July 2011. A fog machine was kept running continuously to create an atmospheric haziness in the Pieterskerk. Different areas were designated for different aspects of the production process: management, costumes and make-up, technique, a waiting room for the models, and catering. The original objects from Museum De Lakenhal and some 16 th century books from the Leiden University Library Special Collections that were used as props in the photographs were collected and taken back to the institutions every day; while in the church they were continuously guarded by a conservator from the museum. The set designer managed the props that came from sources of all sorts; historicizing costumes were rented from as far away as in London, or sewn on the spot by clothing specialists; objects were manufactured specifically for this shoot, borrowed from a taxidermist or (like the food for the still lifes) bought at the market the same morning. Quite deliberately, Olaf introduced some contemporary cloth or details in the outfit of all the models. ‘I do not want this to be a costume ball. The works must be playful, with a nod to the present, so that people today are more easily drawn in an feel able to identify themselves”.[18]

|

Fig. 12 Erwin Olaf, trial shot by Erwin Olaf for the study of composition and lighting, in which the Leiden amateur photo club served as stand-ins, Pieterskerk, Leiden, 4 July 2011 |

Each of the three days, a different section of the history piece was photographed, with a different cluster of figures each time: right, middle and left. The individual portraits and figure pieces of the figures from that scene were shot the same day on other places inside the church, so that each model had to perform and work on the set for only one day. In the post-production, back in Olaf’s studio in Amsterdam, the three sections were assembled into one image in the computer with Photoshop software. A specialist in highlighting, contrasts and colour – what used to be the darkroom work in days of analogue photography – came especially from Barcelona, the same person Olaf had worked with for the Gijon series. Like his predecessors in their painters’ studios, Olaf acted as a director for a large team of specialists in all aspects of production. However large the team of experts; Olaf was the directing artist, and there was no single detail regarding which he did not make his own decisions.

position

The series of the relief of Leiden as it was done by Erwin Olaf fits in a trend in which lens-based media photography and video art are explicitly re-using compositions and iconographic formulae derived from the history of painting. The last time when lens-based media had been so closely tied with painting was during pictorialism in the late 19 th and early 20 th century.[19] This era came to an end after the argument, advanced by constructivism in Soviet Russia and the Bauhaus, for a photographic and cinematic language for photography and film, apart from the visual syntax of historical painting. Modernist photography and film were connected instead with the graphic arts, bordering on them by working with the graphic effects of light reflections and abstracting reality by picking unexpectedly high or low camera positions. The ultimate modernist effort to pry photography loose from figuration altogether, the conceptual photography of the 1960s and 1970s, was firmly rejected by the artist Jeff Wall. Since the 1970s this artist has played a key role in formulating how modernism in photography declined. While working in photography, he reinforced the formulae of tableau-like painting again.

Wall argues that conceptual photography turned out to be a dead end: ‘The other arts, most prominently painting, have tried to invent themselves “beyond” depiction.’[20] Photography instead, he writes, is intrinsically marked by its obligation to mimetically depict a certain reality. ‘Photography cannot find alternatives to depiction,’ as ‘[i]t is in the physical nature of the medium to depict things’.[21] As Wall sees it, photo-conceptualism was ‘the last moment of the prehistory of photography as art’ and ‘the most sustained and sophisticated attempt to free the medium from […] its ties to the Western Picture’.[22] Wall concludes that it failed to do so.

Various theoreticians like David Green and Jean-Paul Chevrier have been developing Wall’s line of thought further. As of around 1974, Green points out, ‘any definition of the medium of photography would have to accommodate its function-as-representation’.[23] Chevrier wrote how at the end of the 20 th century ‘Many artists, having assimilated the Conceptualists’ explorations to varying degrees, have revised the painterly model and use photography, quite consciously and systematically, to produce works that stand alone and exist as “photographic paintings”’.[24] The students of Bernd and Hilla Becher should be mentioned here. Although starting from documentary photography, the increase of the sizes of their prints alone made their work recall the experience of the grand tableau again.[25] It was Andreas Gursky, among these photographer-artists, who also started to extensively manipulate his images digitally, thus bringing them closer to the constructive character of the composition of paintings.

Jeff Wall, using large-size images and computer manipulation as well, was deeply inspired by the complex use of space, composition and figures in the giant painting The Death of Sardanapalus (1828) by Eugène Delacroix.[26] However, as much as paintings were important to him in the complex assembly of photographic imagery, the visual idiom, the choices of compositions, environments and styles are those we recognize as belonging to 20 th and early 21 st century documentary photography.

The video artist Bill Viola has equally been fascinated by the history of painting. However, more than Gursky or Wall, Viola goes into the narration of meanings and human emotions by interpreting old archetypal figures and symbols anew. He vividly tightens up the bonds with Renaissance painters like Giotto and Pontormo from Italy and early Netherlandish painters like Dieric Bouts and Jeroen Bosch.[27] According to the theoreticians Hilde van Gelder and Helen Westgeest, the references to painting by artists like these are the foremost endeavours in rejuvenating a long-dormant figurative painterly tradition in photography.[28] They cite the term “remediation”, that was used in media theory by Jay David Bolter and Richard Grusin to refer to this process of the representation and renewing of tradition of one medium in another.[29]

history painting into history photography

The series by Erwin Olaf on the relief of Leiden is a case of remediation of the old tradition of history painting, into a renewed but comparable tradition in photography. Like Gursky, Wall and Viola, Erwin Olaf had been exploring artistic aspects of tableau-like images: size, composition, use of light, symbols, attributes, costume, pose, gesture and facial expression.

Yet, there is another point of similarity to historical painting present in Olaf’s work on the relief of Leiden; an aspect which has been mentioned by Viola as of great importance in painting. Viola refers to the time when, in his early twenties, he worked in Florence. ‘All the works I had studied in art history class I found to be an active part of the culture, present in the community in public places. […] I mean the churches, the chapels, municipal buildings, piazza’s […]. A lot of the art was still in the places it had been created for. It was the first time I’d ever seen artworks in their proper contexts, and that left a deep impression on me.’[30] Along with the remarkable visual interpretations Olaf gives to the subjects and historical figures, it is precisely this that makes his imagery on the relief of Leiden a remarkable case.

The context and function of Olaf’s history piece and series make them the ‘active part of the culture’ which struck Viola as so important in Florence. Whereas works by Gursky, Wall and Viola are artistic explorations in visual formulae of painting, the Relief of Leiden by Olaf is not only that, but also a vehicle for the vivid commemoration of collectively cherished history, just as history paintings used to be. Hanging side-by-side with its 17 th and 19 th century predecessors, it functions in the same way and thus comes even closer to the heart of the tradition of old painting. One could say that more than the works of the artists mentioned above, and more than earlier work by Olaf himself, The Relief of Leiden is remediation of paintings on a specific theme into photography, of history painting into history photography in a very pure form.

An important question remains. What has this case of remediation of painting into photography added, more than just a change in technique? Would it have been very different had the scene been the same, but executed in paint? The main addition of photography of a scene, compared to the same scene depicted in painting, is the sensation of the real that photography evokes. However staged, highly constructed and digitally manipulated the works by Erwin Olaf are, the fact that all the pictorial parts of the scene have been mechanically reproduced by the camera in highly detailed, graphical images, contributes to the viewer’s perception that this scene is very close to his or her daily experience of reality, and easy to step into. This effect is intensified by Olaf through his introduction of contemporary details into the scene – an intervention which, by the way, has often been employed by artists, for example Caravaggio, to make their imagery more accessible to their contemporary public. Because of this sensation of reality that is so typical for imagery made by the camera, it is especially easy for a viewer to mentally ‘enter’ a scene and identify with the historical content, despite its being remote in time. Staged and constructed photography, compared to painting in the same genre, is better able to form a bridge between our daily experience of reality and the mentally-shaped imagery of an imaginary scene.

There is still another aspect, according to Erwin Olaf, to the remediation of history painting into photography. His remark that photojournalism has taught the harsh reality of war to the public, has an interesting implication. It suggests that the tradition of war photography by photographers like Alexander Gardner, Roger Fenton and Robert Capa, which since the 19 th century has been spreading images of the brutal ugliness of destruction and death, has also brought renewal to the pictorial tradition of visualizing historical conflicts. With the medium of photography, Olaf introduces the unidealized depiction of the cruelty of war, which has always belonged to the tradition of war photography, into the practice of making history pieces.

Erwin Olaf’s artistry in this project not only lies in his controlled way of handling his medium, the materials, and in his skills in staging and directing these large numbers of people – to which he himself added figures that are difficult to direct, like a woman with Down’s syndrome, a two-year old child and a live dog. In this case his mastery also lies in the way he was able to operate in the midst of all forces that came together in this commission: the tradition of previous paintings on the subject to which he had to relate, the existing histories and the newly acquired visions on the subject matter that he had to take into account, and the wishes of his clients. This are all aspects which are identical with those found in the big commissions for programmatic paintings in the past, and characteristic for art in situ. Compared to Gursky, Wall and Viola, in this series Erwin Olaf takes an extra mental step in the transformation of painterly traditions into photography, in that he not only makes art that reflects on historical art works, the implications of which are well understood by people who are informed about the tradition to which the artist is adding. The Relief of Leiden by Erwin Olaf is a full-grown manifestation of photography functioning as history painting in all its aspects: beside being an art work it functions as a means of communication for the commemoration of collectively cherished memories of important past events. It is a good example of the new art form, into which history painting has remediated: history photography.

.

Maartje van den Heuvel

Leiden University

Illustrations

1. The Sea Beggars marching into Leiden as liberators of the besieged city.

2. Minerva, goddess of arms during the relief of Leiden.

3. Jacob van der Does, military advisor and cousin of commanding officer Jan van der Does. Together with Jan van Hout, Jacob and Jan van der Does were referred to as the ‘hawks’: the more militant leading figures of the relief of Leiden.

4. Jan van der Does, commanding officer and ‘hawk’ during the siege and relief of Leiden,

5. Jan van Hout, city administrator and a third ‘hawk’ in the relief of Leiden.

6/7. Soldiers erect a gallow, by order of the Leiden military governor Van Broncorst.

8. Plague doctors, with herbs that would prevent them from catching the plague themselves in their beak-like masks. In this depiction of the relief of Leiden, compared to older ones, attention has shifted from hunger to the plague. This allowed Olaf to introduce the figures of the plague doctors.

9. Merchant, inspired by the painting Portrait of an African man (circa 1525-1530) van Jan Janz. Mostaert.

10. Mayor Van der Werf putting forward his arm, referring to the traditional iconography in which he is depicted offering his body to the hungry citizens of Leiden.

11. Magdalena Moons, a lady from The Hague, fiancée of the Spanish commanding officer Francisco de Valdés. She is holding him back from attacking the city of Leiden.

12. Francisco de Valdés, Spanish commanding officer during both the sieges of Leiden in 1573 and 1574.

13. Spanish soldier.

14. Leiden citizen trying to catch a carrier pigeon. Would the note on this pigeon have news on the approaching Beggars?

15. Dirck van den Broncorst, military governor. He had the gallow erected in Leiden in 1574 to threaten the Leiden citizens with death if they considered to surrender. He died of the plague himself.

16. Andries Allertsz., commanding officer of the militia and freebooters. He died during a sortie near Leiderdorp in the night of 25 May 1574. He was succeeded up by Jan van der Does.

The other figures are soldiers and the suffering people of Leiden.

|

Fig. 16 Erwin Olaf, Plague Doctor, 2011, chromogenic print, 80 x 60 cm, from the series: The Siege and Relief of Leiden (2011), commissioned by Museum De Lakenhal and Leiden University |

Notes

1. Actually, this was the second siege of Leiden, after a similar one which lasted from October 1573 to March 1574 that was interrupted because the Spanish besieging troops were needed elsewhere.↑

2. For a comprehensive account of this story in its historical context, see Israel (1998), pp. 179-184. The historian Judith Pollmann is currently directing a research project entitled Tales of the Revolt. Oblivion, memory and identity in the Low Countries, 1566-1700, focusing on the impact of memories of the Dutch Revolt on personal and public identities in the 17 th century Low Countries. See www.talesoftherevolt.leidenuniv.nl, accessed on 19 July 2011.↑

3. See Otterspeer (2008)↑

4. The same moment of liberation and the distribution of food was painted in 1615 by Pieter van Veen, Otto’s younger brother. Neither Otto or Pieter (1563-1629) were witnesses to the siege and the relief of Leiden themselves. Their brother Simon however was, and it is probable that his reports of the events to his brothers formed the basis for their paintings.↑

5. Although not about the history and history paintings of the Relief of Leiden specifically, Haskell (1993) is an interesting book on the way art of different times can reflect and communicate history in different ways. ↑

6. Reyntjes made his painting autonomously and presented it to the city of Leiden.↑

7. “De Lakenhal” in Dutch means ‘the textile hall’, which refers to a former industry in the town.↑

8. Founded in 1953. See Van den Heuvel and Van Sinderen (2010).↑

9. The project, directed by Professor Judith Pollmann, started on 1 September 2008 and ends on 31 August 2013.↑

10. Martin (2008).↑

11. Statement by the photographer in the documentary Van Erp (2009).↑

12. There is one photograph after a painting by the Italian painter Caravaggio. The box with the series of seven photographs was acquired by Leiden University Special Collections in 2010.↑

13. One of the results of the research project Tales of the Revolt. ↑

14. Smallenburg (2011).↑

15. Aside from three accompanying curators (one of history and one of contemporary art from Museum De Lakenhal, and one of photography from Leiden University’s Special Collections), there were 36 models and 20 assistants. See the appendix for a list of the assisting crew.↑

16. This casting took place on 20 May 2011.↑

17. Most of them were found through professional casting studios that usually work for the advertising and fashion industry. ↑

18. Statement by the artist during the photo shoot, 7 July 2011. ↑

19. For general surveys of the ties to painting this movement in photography had, see Ribemont (2006), Nordström (2008), and for the specific Dutch situation Van den Heuvel (2010)↑

20. Wall (1995) p. 247.↑

21. Idem.↑

22. Idem, p. 266.↑

23. Dobai (2009), p. 107. The representation here of the way the various theories on this subject developed , is based on Van Gelder and Westgeest (2011), p. 51-54.↑

24. Chevrier (2004 [1998]), p. 114.↑

25. Gronert (2009)↑

26. Wagstaff (2005), p. 7-8.↑

27. Bill Viola (2003). See Hanhardt and Viola (2002) for a conversation on the ties to painting in Viola’s works. ↑

28. Gelder, Van and Westgeest (2011), p. 53.↑

29. Bolter and Grusin (2000 [1999]), p. 273.↑

30. Belting and Viola (2003), p. 197.↑

Reference list

Belting, Hans and Viola, Bill (2003) ‘A conversation’, in: John Walsh (ed.) (2003) Bill Viola: The Passions, Los Angeles (Getty Publications), p. 189-220.

Bolter, Jay David and Grusin, Richard (2000 [1999]) Remediation: Understanding new media, Cambridge (MIT).

Chevrier, Jean-Francois (2004 [1998]) ‘The adventures of the picture form in the history of photography’, in: Fogle, D. (ed.), The Last Picture Show: Artists Using Photography, 1960-1982, Minneapolis (Walker Art Center), p. 113-128.

Dobai, Sarah et al. (2009) Theatres of the Real, with essays by Jan Baetens, David Green and Joanna Lowry, Brighton/Antwerp (Photoworks/FotoMuseum Antwerpen).

Erp, Michiel van (2009) Erwin Olaf: On Beauty and Fall, 2009, documentary on dvd-video, 55’, s.l. [Amsterdam] (PIAS).

Gelder, Hilde van and Westgeest, Helen (2011) Photography Theory in Historical Perspective, Case studies from contemporary art, Chichester (Wiley-Blackwell).

Gronert, Stefan (ed.) (2009) Die Düsseldorfer Photoschule : Photographien 1961-2008, München (Schirmer/Mosel).

Hanhardt, John and Viola, Bill (2002) Going Forth by Day, New York (Guggenheim Museum Publications).

Haskell, Francis (1993) History and its Images : Art and the Interpretation of the Past, New Haven & London (Yale University Press)

Heuvel, Maartje van den, and Sinderen, Wim van (2010) Photography! A Special Collection at Leiden University, Leiden/The Hague (Leiden University/The Hague Museum of Photography).

Heuvel, Maartje van den et al. (2010) In atmospheric light : pictorialism in Dutch photography, 1890-1925, Zwolle (Waanders).

Israel, Jonathan (1998) The Dutch Republic : its rise, greatness, and fall, 1477-1806, Oxford (Clarendon Press).

Martin, Lesley (2008) Erwin Olaf, with an essay by Alasdair Foster, New York/London (Aperture/Thames & Hudson).

Nordström, Alison et. al. (2008) TruthBeauty : pictorialism and the photograph as art, 1845-1945, Vancouver (Vancouver Art Gallery/Douglas & McIntyre)

Otterspeer, Willem (2008) The Bastion of Liberty : Leiden University Today and Yesterday, Leiden (Leiden University Press)

Smallenburg, Sandra (2011) ‘Leidens Ontzet op modern historiestuk’, NRC Handelsblad, 9/10 July, p. 13.

Viola, Bill (2003) ‘Sources’, in: John Walsh (ed.), Bill Viola: The Passions, Los Angeles (Getty Publications), p. 223-255.

Wagstaff, Sheena (2005) Jeff Wall: Photographs 1978-2004, London (Tate Publishing).

Wall, Jeff (1995) ‘Marks of indifference: Aspects of photography in, or as, conceptual art.’ In: Goldstein, Ann and Romimer, Anne (1995) Reconsidering the Object of Art, 1965-1975, Los Angeles/Cambridge(MA)/London (Museum of Contemporary Art/MIT), p. 246-267.

Wolf, Hans de (ed.) (2011) Jeff Wall: The Crooked Path, Antwerp/Brussels (Ludion/BOZAR).