Images Inventées in Brussels and The Hague

The emergence of photography as an art form in Belgium, 1950-1965Tamara Berghmans

Extract

Post-war photography in Belgium can be seen in the light of the dominant existentialism of the 1950s, with which the artist’s individualistic thinking and acting fit well. Modern art photography in Belgium went through a crucial phase between 1950 and 1965, which was to be definitive for the course of Belgian photographic history. A small group of photographers – Robert Besard, Pierre Cordier, Julien Coulommier, Gilbert De Keyser, Antoon Dries, Marcel Permantier and Serge Vandercam – fought for the acknowledgement of photography as art at a time in which, in Belgium, there was little consciousness of the possibilities for photography in general. This article will examine the importance that the photo exhibition Images Inventées had in achieving foreign recognition and piloting photography into the Belgian art world. The organizers worked together with the German photographer Otto Steinert, who lent the exhibition added prestige and an international character. The recognition became still more manifest when Images Inventées travelled on to the Vrije Academie in The Hague and Das Städtische Museum Schloß Morsbroich in Leverkusen, Germany.

1. Introduction

After the Second World War Europe was dominated by reconstruction and rebuilding life in general. After all, the war had not only affected the physical environment and industry, but also the intellectual climate. The avant-garde of the inter-war years, and the existentialism of Jean-Paul Sartre (1905-1980) provided new tools for understanding life. Man was central to this thought: the subject was brought to the foreground. Existentialism was further characterized by an emphasis on individuality, individual freedom and subjectivity. Phil Mertens (1928-1989), former director of the department of Modern Art at the Musées royaux des Beaux-Arts de Belgique in Brussels, summed it up thus: ‘Isolation and existential experience always dominated the spirit of these first post-war years. Although this attitude was not operative in Belgium either explicitly or unconsciously, its traces were nonetheless to be found.’[1] Most people were not consciously involved with this philosophical current, nor had they read books by Sartre and Albert Camus (1913-1960). Rather, it was the intellectual outlook that was permeated with an ‘existential’ mood.

Post-war photography in Belgium can also be seen in the light of the dominant existentialism of the 1950s, with which the artist’s individual thinking and acting fit well. Modern art photography in Belgium went through a crucial phase between 1950 and 1965, which was to be definitive for the course of Belgian photographic history.[2] In this article ‘modern art photography’ will be understood as photography that aspires to be art (in contrast to applied and/or documentary photography), and which thereby also explicitly distinguishes itself from the traditional salon photography of pictorialism. This photography drew on specifically photographic means and a new way of seeing in order to achieve its objective. Modern is here used with the meaning of ‘contemporary’, that is, of its time. This also implies always seeking the new, and disassociating itself from the traditional or conservative. In post-war modern art photography, photographers drew upon the concept of Subjektive Fotografie, propounded by the German photographer Otto Steinert (1915-1978), photographic techniques from the Neue Sachlichkeit and the Neue Sehen, and abstract painting. This photography differs from that of the 1920s and 1930s, however, because it has the subject, rather than the object, as its prime concern. The photographer’s personal expression is central.

A small group of photographers – Robert Besard (1920-2000), Pierre Cordier (b. 1933), Julien Coulommier (b. 1922), Gilbert De Keyser (1925-2001), Antoon Dries (1910-2004), Marcel Permantier (1918-2005) and Serge Vandercam (1924-2005) – fought for the acknowledgement of photography as art at a time in which, in Belgium, there was little consciousness of the possibilities for photography in general. This period preceded the institutionalization of photography: there were no academic courses in photography, there were no regulations regarding photography as a profession, and there were no specific exhibition venues.[3] Modern art photography developed primarily in photo clubs, and to some extent in the avant-garde art world. The blending of these two different climates, sets of ideas, networks and friendships, this dyad of amateur and avant-garde, also created a tension in the vision of the photographers: on the one hand they sought connection with the art world, on the other they could not let go of the amateur milieu.[4]

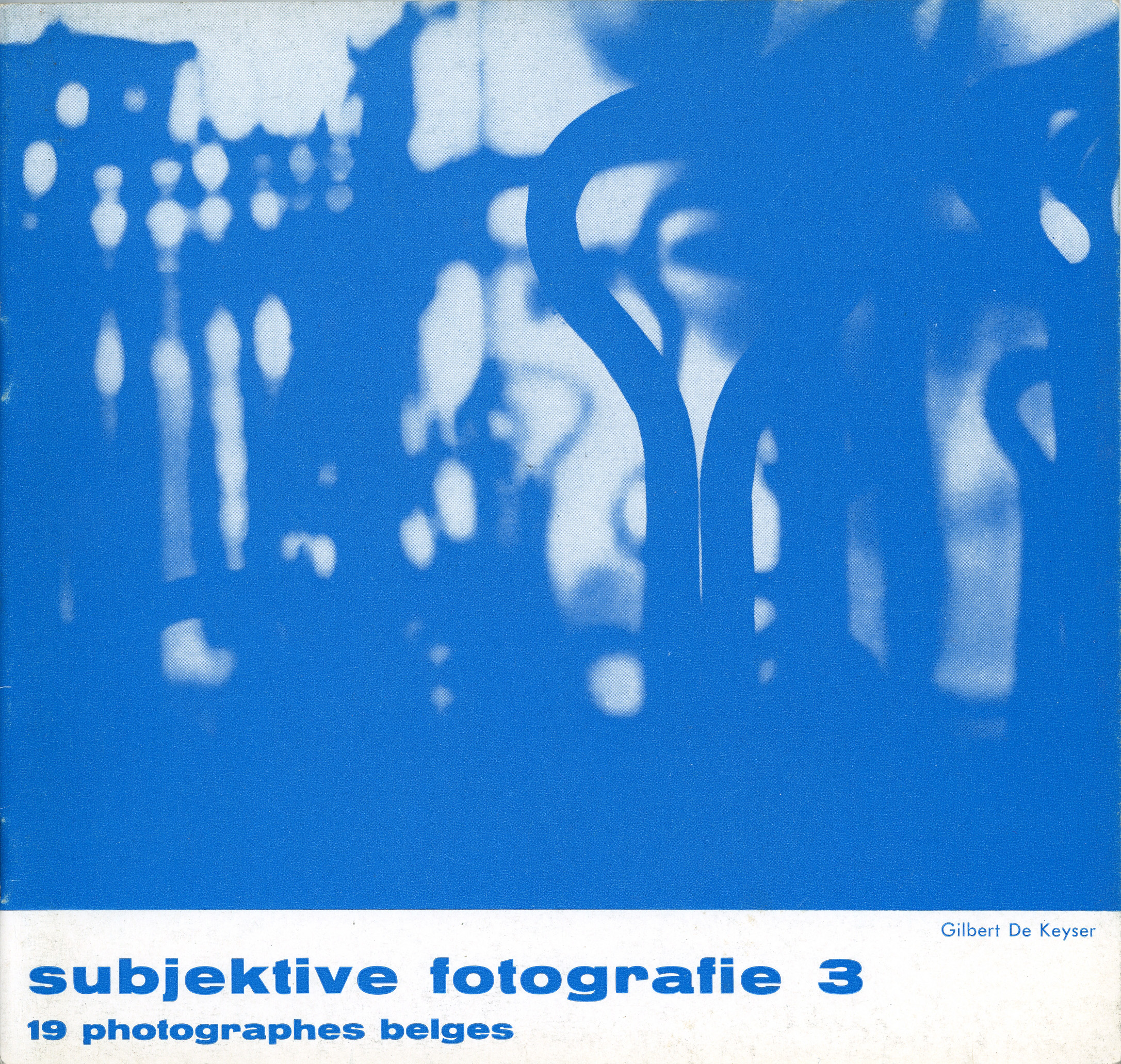

In this post-war period the Palais des Beaux-Arts in Brussels, an exhibition space without a collection, fulfilled a role in the Belgian art scene which must not be underestimated. Its most important players were Robert Giron (1897-1967), director of the Palais des Beaux-Arts, and Emile Langui (1903-1980), Administrator General for Fine Arts. After the Second World War there were no museums for modern art in Belgium. The only Museum for Modern Art in Brussels closed its doors in 1959,[5] at precisely the moment that everywhere else in the world museums such as the Moderna Museet in Stockholm and the Guggenheim Museum in New York were opening theirs. No other post-war exhibition centre in Belgium had such a flourishing existence as the Palais des Beaux-Arts.[6] Not only the foremost visual arts events, but also the most important international photography exhibitions of the 1950s took place there, such as The Family of Man (1956), Images Inventées (1957) and Subjektive Fotografie 3 (1959).

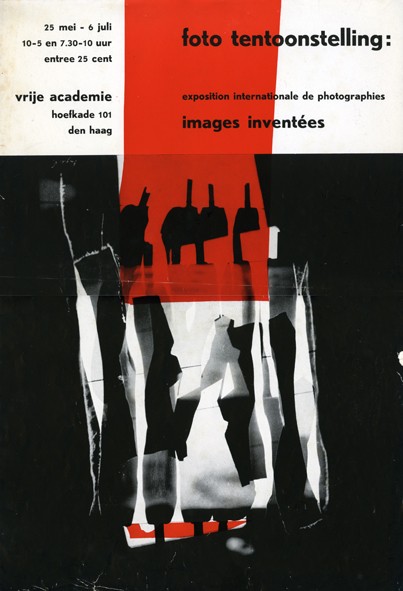

This article will examine the importance that Images Inventées had in achieving foreign recognition and piloting photography into the Belgian art world (fig. 1).[7]

|

Fig. 1 Poster for Images Inventées, The Hague (Wezembeek-Oppem, Private collection of Julien Coulommier) |

The organizers worked together with Otto Steinert, who lent the exhibition added prestige and an international character. The recognition became still more manifest when Images Inventées travelled on to the Vrije Academie in The Hague and Das Städtische Museum Schloß Morsbroich in Leverkusen, Germany.

I will first sketch how Otto Steinert’s concept of Subjektive Fotografie was understood in Belgian modern art photography between 1950 and 1965, and more specifically what contacts existed between Steinert and the Belgians. The impetus for renewal it provided crept in primarily through the Fotografische Kring IRIS in Antwerp and the Photo-Ciné Club de Boitsfort in Brussels.[8] In contrast to the tendency toward separation which existed in most countries, the modern movement in Belgium grew up in the existing photo clubs. As the fresh ideas of the young photographers gained strength, a real conflict broke out in the photo clubs between the ‘moderns’ and the ‘traditionalists’. Second, I will specifically go into the organization and reception of the exhibition Images Inventées at the Palais des Beaux-Arts.

2. Subjektive Fotografie in Belgium

Already at the time it was first launched, the concept of Subjektive Fotografie was the object of confusion among critics, art historians and photographers. There were repeated discussions about the true meaning of Subjektive Fotografie. In fact, in his own discourse Otto Steinert never provided an unambiguous definition. In 1951 Steinert emphasized that the photographs exhibited were diametrically opposed to applied and documentary photography: ‘This exhibition has taken as its motto “Subjektive Fotografie”, for this idea expresses pithily and in heightened fashion the personal creative moment of the photographer (as opposed to “applied” photography serving everyday or documentary purposes)’.[9] Several paragraphs later he also embraced personal reportage: ‘The concept of “subjektive Fotografie” is accordingly taken by us in the sense of a framework embracing all fields of personal creation in photography – from the abstract photogram to the “reportage” or photographs in connected series, psychologically developed and pictorial in form.’[10]Subjektive Fotografie was a portmanteau concept which brought together a great deal of international art photography from the 1950s in three exhibitions between 1951 and 1958. Creativity and experimentation were central to this heterogeneous group of images. The photographer himself was the true subject of the often strongly formal photographs. Any experimentation with purely photographic techniques was in the service of personal expression.[11] The photographer’s creative impulse was at the heart of the project, and the iconic dimension of the photography was often radically suppressed by thoroughgoing abstraction of the image. Jean-Claude Lemagny, the curator of the Cabinet des Estampes et Photographie at the Bibliothèque Nationale de France associates Subjektive Fotografie with existentialism, which upheld the radical freedom of the individual. But at the same time he notes that this freedom was restricted by the fundamental conditions imposed by photographic technique. [12]

Belgian photographers were quite familiar with the concept of Subjektive Fotografie. Marcel Permantier interpreted it as a sort of extension of his inner self, and regarded photography as a quest for poetry.[13] According to Julien Coulommier, Subjektive Fotografie would mean ‘a definitive and formal break between a new form reflecting on the possibilities for plastic expression in photography and an activity that includes both craftsmanship and the reverential mimicry of painting.’[14] In Subjektive Fotografie Robert Besard saw the freedom of the photographer ‘to intervene in the process of creating a photograph, but doing so exclusively by photographic means’. He pointed to interventions like solarization, negative printing and bas-relief, which could be used to express oneself and be present in the photograph.[15]

In all these visions, one finds an emphasis on the person of the photographer (poetry, one’s own world, self-expression) on the one hand, and on the other on the importance of technique (specifically photographic means, manipulation). In Belgium Subjektive Fotografie was seen as an umbrella term for creative photography (thus: art photography), which was to be distinguished from journalistic or other documentary photography. In this photography the photographer himself was central, a figure who brushed aside reality and revealed a new, imagined world of his own.

|

Fig. 2 Julien Coulommier, Anthropologie IV, 1962, gelatin silver print, 49,5 x 59,5 cm (Antwerp, FotoMuseum; © Julien Coulommier) |

The whole Subjektive Fotografie movement was a strongly international current, in which Belgian photographers found a place for themselves. In his portraits of his son Robert Besard shows us a sombre and melancholy world; Pierre Cordier discovered a new medium in the form of the chemigram; Julien Coulommier brought a spine-chilling botanical world to life (fig. 2); through close-ups of materials, Gilbert De Keyser evoked personal feelings (fig. 3); Antoon Dries explored his vision of the medium of photography through nature (fig. 4); Marcel Permantier applied scores of darkroom techniques, and in his fascination for the gaze Serge Vandercam found a plasticity in the objects around him (fig. 5). Among these photographers abstraction, emotion, poetry, techniques, matter, anthropomorphism, experimentation and the legacy of surrealism and pictorialism were key issues. In their oeuvres we see elements such as disorientation, fragmentation, the creation of subtle moods, interest in texture and material. Compared with countries like Germany (Otto Steinert) and the United States (Minor White), the Belgians were not theoreticians, but intuitive and emotional photographers, whose attention was not devoted to man and his world, but to strongly abstract images that reflected the photographer’s inner emotional world. In contrast to socially engaged photo reportage, humanistic photography and the avant-garde photography from between the wars, among the Belgian modern art photographers there was little or no pronounced social engagement and/or political preference. No explicit critical social vision was visible in their work. It is not however that they were reacting against the society; their critique was first and foremost directed against traditional salon photography.

|

Fig. 3 Gilbert De Keyser, Surgissement, 1955, gelatin silver print, 59,2 x 49 cm (Charleroi, Musée de la Photographie; © Gilbert De Keyser) |

In Belgium Julien Coulommier was the key figure in the battle to have modern art photography accepted as an autonomous art form. He was not only recognized for his qualities as a photographer, but he also earned praise as a critic and exhibition curator in the post-war period. He was the one who was most vocal in promoting Steinert’s ideas and familiarizing Belgian and Dutch audiences with them. He wrote articles in the best-read photographic journals nationally and internationally, and he was invited to defend his opinions as an expert with actual experience in the field. Through his good contacts with photographers in other countries and with the art scene, Coulommier played a vital role in facilitating the organization of an international, travelling exhibition like Images Inventées, and his role in bringing Subjektive Fotografie 3 to Brussels was crucial. Because of his views on photography, which were controversial among many amateur photographers, he had both supporters and opponents. Nevertheless, he was the contact person for Subjektive Fotografie in Belgium.

3. Under Steinert’s wings

Otto Steinert believed in the power of photography. He was not only enthusiastic about it himself but also had the capacity to awaken an enthusiasm for the medium among others. He occupied a central position in the post-war photo world. Steinert was a remarkable personality, whose work and judgement was respected in diverse circles: both by experimental art photographers and by professional photographers, both at the amateur level and in the art world. Many photographers saw Steinert’s approbation as an important stamp of approval. He was a charismatic figure and had a very extensive international network.[16]

The contacts between him and the Belgian modern art photographers were both good, and regular. For instance, in 1953 Fotoform showed for the first time in Belgium, in Charleroi. Fotoform was a group of like-minded photographers, comprised of the Swede Christer Christian (1918-2002) and the Germans Otto Steinert, Wolfgang Reiseweitz (b. 1917), Heinz Hajek-Halke (1898-1983), Peter Keetman (1916-2006), Siegfried Lauterwasser (1913-2000), Toni Schneiders (1920-2006) and Ludwig Windstosser (1921-1983). The group was originally founded by Reisewitz as a critique of the selection procedure for an exhibition organized in 1949 in Neustadt an der Haardt.[17] Steinert’s concept of Subjektive Fotografie grew out of Fotoform, after he joined with this group in participating in the first Subjektive Fotografie exhibition in 1951.

|

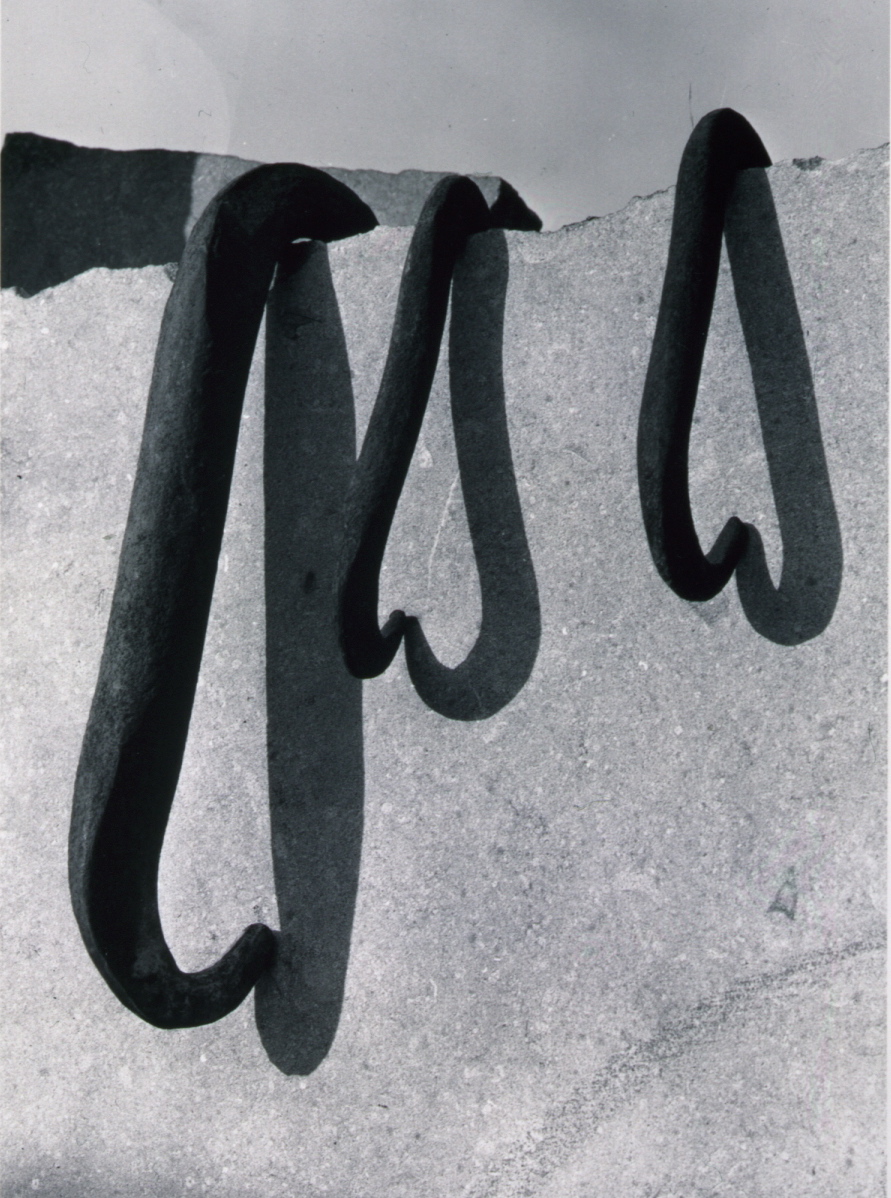

Fig. 5 Serge Vandercam, Les crochets, 1952, gelatin silver print, 50,5 x 40,9 cm (Essen, Fotografische Sammlung im Museum Folkwang; © Serge Vandercam) |

In 1954 the photographer and painter Serge Vandercam showed work at Subjektive Fotografie 2 (fig. 5).[18] After seeing these photographs in Saarbrücken, Julien Coulommier made contact with Vandercam and Steinert.[19] After 1954 it was Coulommier who propounded Steinert’s vision in Belgium. He went to Germany as a correspondent for the Dutch periodical Foto, wrote various articles, interviews and book reviews for other journals, gave lectures and organized Images Inventées. After the end of this exhibition Steinert congratulated Coulommier with the progress he had made: ‘Zu Ihrer eigenen Ausstellung darf ich Ihnen noch herzlich gratulieren, ich finde Sie haben eine sehr positive fotografische Entwicklung in der letzten Zeit durchgemacht. Hoffentlich bleibt der äussere Erfolg hierfür nicht aus.’[20] That these were not empty words is clear, first from the fact that Steinert also brought the exhibition to Germany, and second from his announcement in the same year that his next Subjektive Fotografie exhibition would include various Dutch and Belgian photographers: ‘[…] Ich kann heute schon mitteilen, das ich für die “Photokina 1958” eine “Subjektive Fotografie 3” und “Das fotografische Selbstporträt” vorbereite. Bei beiden Ausstellungen hoffe ich auf recht umfangreiche Bildkollektionen aus Belgien und Holland, und darf ich Sie um Ihre Unterstützung hierbei bitten.’[21]

|

Fig. 6 Marcel Permantier, Portrait Robert Besard, Prof. Dr. Otto Steinert, Julien Coulommier, Brussels 1958 (Kraainem, Private collection of Robert Besard; © Marcel Permantier) |

It was primarily the photographers of the Photo-Ciné Club de Boitsfort and Julien Coulommier who maintained good contacts with Steinert. In 1955 Steinert was received as a guest of honour at their Festival d’Art photographique in the Brussels City Hall, and in 1957 he was shown in Images Inventées.[22] In 1958 Steinert, along with the Frenchman Jean-Pierre Sudre (1921-1997) and the Dutch photographer and Nederlandse Fotografen Kunstkring (NFK) member J.J. Hens, had seats on the jury for La photographie belge jugée par l’étranger, sponsored by the new Brussels photo club Filmart (fig. 6).[23] Various collaborations grew out of this event. For instance, it was here that Pierre Cordier made his first contact with Steinert.[24] In March Steinert gave Cordier permission to register for the summer term at the Staatlichen Schule für Kunst und Handwerk in Saarbrücken, and at the same time asked him to bring along some works, so that several could be selected for Subjektive Fotografie 3.[25] In addition, it was there that Steinert picked out Belgian photographers for the 1958 exhibition Fotos aus Belgien (Photographs from Belgium) in Cologne. And, as icing on the cake, in 1959 the Photo-Ciné Club de Boitsfort, in cooperation with the Palais des Beaux-Arts, brought Subjektive Fotografie 3 to Brussels, combined with a presentation of 19 Belgian photographers (fig. 7).[26] Steinert’s esteem for the Belgian photographers and Cordier’s chemigrams is clear from his letter of 15 June, 1959, to Cordier: ‘[…] Es war mir persönlich eine grosse Freude in Brüssel ausstellen zu können und darf ich Sie bitten, sowohl den verantwortlichen Herren des Palais des Beaux Arts als auch unseren Freunden des Photoclub Boisfort meinen herzlichen Dank zu übermitteln. Denken Sie bitte persönlich daran, das ich eine Ausstellung der chemofotogramme von Pierre Cordier, in dem von uns vereinbarten Sinne, gerne bald veranstalten möchte.’[27] The valuable contacts between Otto Steinert and Belgium between 1954 and 1959 had clearly borne fruit.

4. Images Inventées

One of the most important results of the collaboration between the Belgian photographers and Otto Steinert was the organization of the international photography exhibition Images Inventées. Not only was this the first time that the crème de la crème of the international photography world were shown in Brussels, but it all took place in the one location where the contemporary visual arts scene ruled the roost. The Palais des Beaux-Arts wanted to be a dynamic home for art, which gave priority to Belgian and international art. Its foreign exhibitions of modern art had enormous influence on Belgian artists. The art of the occupation years was rejected, and through the post-war period the Palais des Beaux-Arts followed the evolution of abstract art closely. This did lead to criticism of the exhibition policy at the Palais des Beaux-Arts. Opponents claimed that it paid no attention to other currents and that it influenced Belgian art through its emphatic preference for abstract art. The Belgian art historian Karel J. Geirlandt (1919-1989) noted that abstract art was an international, specifically aesthetic, artistic language, which, in the midst of all its ideological opponents, occupied a specific place in the debate. Precisely because it did not represent reality it could not threaten the ‘the integration of the free world’ by depicting particular values and ideas. Proponents of abstraction believed in its universal value: abstraction was a universal language, understood by everyone. This utopia was significant particularly when ‘it stands out against the dark wall of the events of the recent war and their aftermath.’[28] That photography with far-reaching abstract qualities should have a place in this too, seems no more than logical today.

Images Inventées (Verzonnen beelden), assembled by Julien Coulommier and Serge Vandercam, was to be seen from 30 March to 17 April 1957, in the Galerie Aujourd’hui in the Palais des Beaux-Arts in Brussels.[29] This international photography exhibition was the result of a collaboration between the Galerie Aujourd’hui (director-general, Pierre Janlet) and the Staatliche Schule für Kunst und Handwerk at Saarbrücken (director, Otto Steinert). There were about one hundred photographs shown, by fifty-six photographers, of whom eight were Belgian and forty-eight foreigners, from Germany, England, France, Italy, The Netherlands (including Martien Coppens, Victor Meeussen, Jan Schiet, Willy Schurman, Livinus van de Bundt, Van Houweninge, Pim Van Os, Frans Vink and Meinard Woldringh), Spain, the United States and Sweden (fig. 8).

Coulommier explained in 2004 that the management of the Palais des Beaux-Arts wanted to organize something ‘on the level’ of the Palais des Beaux-Arts, something that was of equal merit with painting. His task consisted of making contact with the photographers who he had seen with Steinert.[30] During the preparatory evenings with Serge Vandercam and Claude Vermeylen, Coulommier met the Belgian artist Marcel Broodthaers (1924-1976). The two had a mutual admiration for one another, which would result in the collaborative project Les Statues de Bruxelles (1957).[31] Broodthaers was not officially a part of the organizing committee, but now and then offered his opinion. According to Coulommier, Vandercam, who had good contacts with the Palais des Beaux-Arts and in this period had already put artistic photography aside, was occupied primarily with his painting and gave him almost total carte-blanche in the choice of the photographs.[32] Pierre Janlet asked for Steinert’s cooperation for the exhibition, and made an appointment for him to meet personally with Coulommier, Vandercam and Vermeylen. They looked at the work together, and made a selection.[33] Apparently Janlet asked for Steinert’s cooperation for a greater sense of assurance. Steinert’s name, and the connection with him, would legitimize the exhibition, and give it a certain cachet and dependability. Steinert’s involvement was a guarantee of quality, and would draw greater attention to the show.

In the letter of invitation sent to the photographers, Janlet indicated the objective of the exhibition and emphasized that the subject was non-figurative photography: ‘By this, we mean photographs in which the personal insight of the photographer has the upper hand over reality. The purpose of the exhibition is to firmly establish the importance of photography as a means for plastic creation.’[34] In the press release, Coulommier made a comparison between photography and painting and sculpture. He suggested that all three were only connected with the visible world to the extent that they chose to be. Coulommier further listed the most important characteristics of this exhibition as ‘artistic standing, a uniform orientation to the non-figurative, and a great diversity in the forms of personal expression.’[35] In this way Coulommier excluded documentary photography, and welcomed abstract photographs in diverse techniques.

The title of the exhibition caused commotion and confusion among both viewers and some of the invited photographers. Nothing in the title Images Inventées / Verzonnen beelden indicated that the works exhibited were photographs. A question which we must ask ourselves – and which many people asked at the time – is therefore, can photographs be invented images? After all, isn’t reality the starting point for photography? Even if what is depicted in the photograph is no longer recognizable, when the subject is abstracted as much as possible, it is still not an invented image. Images Inventées was to play a pioneering role and ‘show photographers the way to an apparently non-representational art.’[36] Just as Steinert had done in his Subjektive Fotografie exhibitions, Coulommier draws our attention to the importance of experimentation in giving form to the photographs, and was furthermore of the opinion that any and all means must be employed to attain a good result.[37] Coulommier took over Steinert’s vision in Images Inventées, and even makes the definition still narrower. In contrast to Steinert, who essentially defined Subjektive Fotografie as all creative photography – including both formal experiments and photograms as well as personal reportage – Coulommier placed the accent on non-figurative experiments. Because of their woolliness, Coulommier’s texts were often unclear. At any rate, in practice there was often little to be seen of the transcendental experience which the photographer must enjoy, according to Coulommier’s theory.

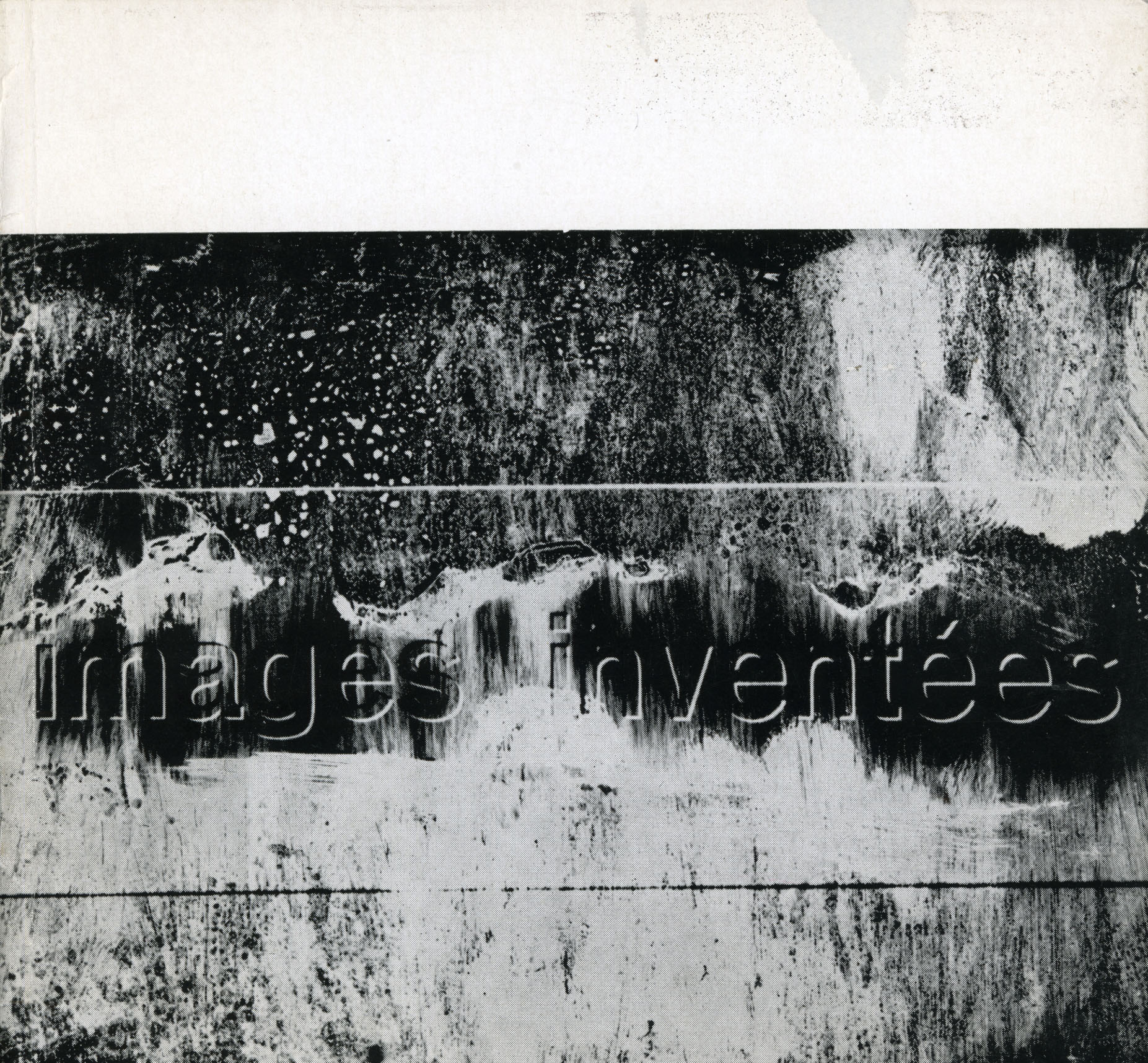

A small, almost square catalogue appeared to accompany the exhibition, with a photograph by Serge Vandercam on the cover (fig. 9), containing the text ‘Une tige bleue de lumière’ (A blue shaft of light) by the Belgian poetess Chris Yperman (b. 1935), ‘De wereld waarin wij leven’ (The world in which we live) by Hans van de Waal, director of the Prentenkabinet (Print Room) at the University of Leiden, and a text by the German art historian J.A. Schmoll gen. Eisenwerth (b. 1915). The Dutch art historian Van de Waal alluded to the end of the Renaissance and to the beginning of a new era, in which a new constitutive element was emerging, which he called ‘the interest in structure’. According to him, one could identify a growing consciousness of spatial structures: ‘These are no longer compositions in the classic sense of that word, but they are patterns (échantillons), that is to say, motifs, that one can expand in any direction. Paradoxically enough, it appears that the camera, that old-fashioned perspective machine, is entirely usable in this modern observation of superficial structures, and it appears from modern graphics created purely with light, more clearly than in any other branch of the contemporary arts whatsoever, that classic composition as form has been replaced by the principle of the échantillon.’ Van de Waal called photography not the mirror of nature, but rather the mirror of our culture: ‘Through (à travers) the magic mirror of these “images inventées”, may many obtain a clearer picture of the world in which we live!’[38]

Schmoll gen. Eisenwerth, a personal friend of Steinert and former instructor at Saarbrücken, pointed to the two sides that photography has expressed in the 120 years of its existence: objective photography (the photo as reproduction) and subjective photography (the photo as art).[39] By putting this text in the catalogue, Coulommier set up a comparison between his exhibition and Steinert’s, for it was Schmoll gen. Eisenwerth who provided the legitimization and context for Subjektive Fotografie.[40]

Not counting the organizers, Julien Coulommier and Serge Vandercam, only six Belgian photographers took part in the exhibition. Thus, it was comprised primarily of foreign photographers. In several of respects Images Inventées resembled the two Subjektive Fotografie exhibitions of 1951 and 1954. Both Steinert and Coulommier sought to create an art-historical basis for the non-figurative photographs that were shown.[41] For this, they both invited several pioneers from the 1920s and 1930s, such as Max Ernst, Man Ray, E.L.T. Mesens, László Moholy-Nagy and Raoul Hausmann, to legitimize their contemporary photographs. Not only did the concepts behind the two exhibitions show strong similarities, but the photographers exhibited were similar in nature. Images Inventées saw thirty-three foreign photographers showing in Belgium for the first time, including Kurt Dejmo, Anders Holmquist, Peter Keetman, Paolo Monti, Lennart Olson, Detlef Orlopp, Roger Perrin, Keld Helmer Petersen, Livinus van de Bundt and Minor White.

5. Images Inventées goes on tour

In the same year Images Inventées travelled to other countries, being shown in The Hague and Leverkusen. It is clear from his correspondence with Raoul Hausmann and Roger Doloy that Coulommier also tried to get the exhibition to Paris. Hausmann thought that the French situation would not be as open to creative photography, however: ‘Une telle chose devrait être montée en France, où, à mon avis, les administrations, telles que la Bibliothèque Nationale, l’Unesco et la Fédération des photographes-amateurs sont les plus grands obstacles pour qu’une photographie créative ou subjective se développe, car les dirigents de ces administrations ne veulent pas d’art et insistent sur le caractère “peinture de genre” que la peinture déjà abandonnée depuis 50 ans!’[42]

In The Hague the exhibition took place from 25 May through 6 July 1957, in the Vrije Academie, with the Dutch title Verzonnen Beelden.[43] The invitation for the exhibition stated that it had first been seen in Brussels, and was now on a tour through Europe and the United States – the latter of which was not the case. Images Inventées was able to travel to The Netherlands as a result of the good contacts which existed between Coulommier and Livinus van de Bundt, who was one of the photographers participating in the exhibition.

Until 1964 Livinus van de Bundt, a graphic artist with a wide interest in everything that had to do with photography, was director of the Vrije Academie, and introduced photography into the curriculum in 1958. The practical and theoretical lessons in photography were given by two NFK-photographers, Victor Meeussen and Ed van Wijk, while Van de Bundt himself took responsibility for the course in visual design.[44]

In the show as it appeared in The Hague the photograph of a girl’s head by Anders Holmquist was removed by Van de Bundt, because, according to him, it did not fit with the rest of the exhibition (fig. 10). The photograph was a portrait of the head of a girl with short hair and dark lips. She is looking directly into the lens with her heavily made-up eyes. Stalks of grass can be seen in the background. Martien Coppens, on the other hand, found that precisely this photo was a good example of real abstract photography: ‘The figurative significance of abstraction is disappearance. In our case this comes down to stripping away incidentals in order to be left with the core of the matter. Abstract and non-figurative are often incorrectly thought to be interchangeable; they are not identical.’[45] This was a good example of the sort of confusion which surrounded the title Verzonnen beelden, and the different possibilities for interpreting the concepts of abstraction and imagined.

|

Fig. 10 Georges Andrien, View of the exhibition Images Inventées, 1957 (Wezembeek-Oppem, Private collection of Julien Coulommier; © Georges Andrien) |

The exhibition went on to Leverkusen from 14 December 1957, through 26 January 1958, in Das Städtische Museum Morsbroich, and was organized there by the Deutsche Gesellschaft für Photographie/Sektion Bild (DGPh). This association had been founded in Cologne in 1951by the photographer and collector Fritz Grüber (1908-2005), who was also a co-founder of the Photokina photography fair. The Städtische Museum Morsbroich in Leverkusen was established in 1951 as one of the first post-World War II museums, and was an institution in which contemporary art and design were shown. Among the important artists who showed in post-war Germany were Lucio Fontana and Yves Klein. The museum assembled a rich collection of contemporary art, ranging from Oscar Schlemmer to Joseph Beuys and nouveau realisme, and from op-art and kinetic art (Group Zero) to minimalist reduction and abstract tendencies.[46] Steinert termed it an honour that photography could be shown there.[47] The fact that he brought Images Inventées to Germany indicated that he was delighted with its quality and selection.

A new catalogue with a different layout appeared to accompany the exhibition in Leverkusen. The French title Images Inventées was retained, with the new title Subjektive Fotografie on the front cover in parentheses. This expressly linked the two exhibitions with one another, and perhaps also equated them. In addition to a new introduction by Otto Steinert, the text by J.A. Schmoll gen. Eisenwerth was taken over from the Brussels catalogue.

6. Remarkable images

Several positive reactions from photographers who had participated in Images Inventées, and somewhat more critical reviews by photographers who had not been selected, appeared in Belgian photographic magazines. According to Coulommier, there was a good crowd for the opening of Images Inventées in Brussels. He attributed this to the fact that Steinert was to have been present, which ultimately was not the case. Most of the attendees were amateur photographers from the Brussels area who had heard of the exhibition and wanted to be sure they were there. Coulommier had informed all the photo clubs and had prepared a special text in which he explained why particular photographs had been selected. By his account, the newspapers did not give much coverage to the opening, because it was still ‘just photography’. Nonetheless, it appears that not all the visitors, or reporters, knew beforehand that the show involved photography.[48]

Photographers who had not been invited to participate, and the more traditionally-minded in the photographic community, responded less positively. Photo club members Albert De Loz and Guy Cockx attributed the success of Images Inventées to people’s curiosity. They spoke of a certain disappointment among visitors, because the works, in contrast to what the poster indicated, were not really imagined. Still, they found that the exhibition was worth at least a brief visit, although there were only a couple of ‘Greats’ to be seen, such as Otto Steinert, Pim van Os, Peter Keetman and Kurt Dejmo.[49]

The press releases were run in various newspapers, such as De Nieuwe Gids, Het Laatste Nieuws and La Nouvelle Gazette [50]. Other papers gave somewhat more attention to the exhibition, with a short description or review of the show. For instance, Maurits Bilcke of the Gazet van Antwerpen (1957) noted that the exhibition was ‘quite remarkable’.[51] The rather conservative Urbain Van de Voorde of De Standaard (1957) warned the reader that he had thought he would be seeing abstract paintings or drawings rather than photos: ‘And yet it is all reality, all images from nature! Has we not been told that the painter should no longer depict nature, because the photographer can do that better than the best realist? And we have proof that he, working with a motif from nature, can photograph it as abstractly as the non-representational painter can invent his “symbols”. If the intention of this exhibition was to defend abstract art, then, to my mind, it achieved the opposite result.’[52]

The Dutch did not have the same interest in non-figurative photography as the Belgians: ‘When the same photographs were shown in May in the Vrije Academie in The Hague, it appeared that interest from the Dutch side was much less.’[53] Meinard Woldringh, of the NFK, was not so enthusiastic about the exhibition. Initially it was not entirely clear to him what, precisely, the aim of the exhibition was. For Woldringh it seemed to go in the direction of Subjektive Fotografie, but delimited much more narrowly.[54] There were two trends in Dutch photography in the 1950s: the ‘art photographers’ of the NFK and the professional and documentary photographers of the Vereniging van Beoefenaars der Gebonden Kunsten in de Federatie (GKf). The NFK was in contact with Steinert, and participated in both the first and second Subjektive Fotografie exhibitions.[55] Still, Woldringh had voiced criticism after the second exhibition: Steinert was putting too much emphasis on the merely formal. In fact, Subjektive Fotografie was greeted with mixed feelings in The Netherlands, by both the GKf and the NFK.[56] One important figure in this was Martien Coppens, who also drew attention to modern, post-war photography with his Fotografie als uitdrukkingsmiddel exhibitions in 1952 and 1957. Coppens emphasized that photography was more than merely a means of reproduction, seeing as photography enabled the photographer to express his personality. Yet he was no unconditional advocate of abstract photography, a stance in which he represented the views of most of his countrymen. Although Dutch photography was open to experimentation – think of Pim van Os and Livinus van de Bundt – the Dutch preferred a more realistic photography in which man was given his place. This contrasted sharply with the work of the Belgians, in which man was hardly present. In the magazine Fotografie in 1957 Martien Coppens voiced the opinion that the title Verzonnen beelden didn’t really cover the import of the exhibition: ‘One can call the photographs in this exhibition invented images, one can call them subjective or even abstract, yet with each of these terms one catches only a part of what is there, because there are some photos that are just not subjective and there are others which are neither abstract, nor invented.’[57] Leaving the real invented work aside, Coppens nevertheless thought the exhibition important: ‘Probably one will curse and grumble under his breath, yet in the end one will begin to understand a bit more – although not necessarily immediately – of the restlessness that torments a number of his colleagues here and in other countries.’[58]

J.J. Hens, who seemed to have been deeply moved by the exhibition, provided a different reaction in Foto (1957). He went deeper into the text by Hans van de Waal and the position of photography as art. According to him, the greatest significance of Images Inventées was that the visual artist was increasingly recognizing the worth of photography. Hens affirmed his respect for the work and the enthusiasm of the organizers, and opined that the exhibition deserved a better publicity campaign.[59]

Between 1950 and 1965 public appreciation for modern art photography grew, although one could still not speak of a great wave of enthusiasm; nonetheless, a consciousness-raising process regarding the possibilities of photography was now under way. The lack of understanding on the part of the vast majority of the population would not be overcome quickly, however. The public could be divided into four groups: photographers (professional and amateur photographers / traditionalists and progressives); the art world (artists, critics); journalists, and the wider public (laymen and art lovers). Their visions differed as much as day and night. Devotees of abstract art defended modern art photography, while others reacted more negatively. On the other hand, there were several important avant-garde art institutions which gave modern art photography exposure, such as the Palais des Beaux-Arts, several Brussels galleries, and the Antwerp artists’ group G 58.

7. Conclusion

The Palais des Beaux-Arts in Brussels, which was one of the most important institutions for contemporary art in the post-war period, assumed a crucial role in recognizing and promoting modern art photography. Everything in the Brussels art world happened in and around the Palais des Beaux-Arts. Both in its exhibitions and in its publications, photography was encouraged and defended by two of the important players there, Pierre Janlet and Robert Giron. Not only were there a number of important solo exhibitions organized (Serge Vandercam, Roland d’Ursel, Julien Coulommier), but the three most important international photography exhibitions to visit Belgium were hung in the Palais des Beaux-Arts. Attention was given to all sorts of modern photography, from the humanistic-oriented photography of The Family of Man to the experimental and often abstract photography of Images Inventées and Subjektive Fotografie 3. Still, not all photo exhibitions appeared in the big galleries of the Palais des Beaux-Arts. Images Inventées was mounted in the smaller Galerie Aujourd’hui. It was there that the personal preferences of Pierre Janlet and the more avant-garde exhibitions were organized.

In the main, photography arrived at the Palais des Beaux-Arts as the result of the contacts that existed between the modern art photographers and several artists who already belonged to the modern art scene. Open-minded individuals such as Jo Delahaut, Maurits Bilcke, Léon-Louis Sosset and Philippe-Edouard Toussaint spoke up for modern photography. In Brussels it was Vandercam who brought Coulommier in touch with artists like Marcel Broodthaers and Chris Yperman. In Antwerp the artists’ group G 58 Hessenhuis was founded in 1958. Along with poets and visual artists, there were also photographers who were members. The connections between Vandercam and Coulommier were very important for the inclusion of photography in the Palais des Beaux-Arts. In addition to these personal friendships, there was also Pierre Janlet’s sincere interest in modern photography. Although the photo exhibitions were not always hung in the best spaces, nor did they always receive the best reviews, this was a world away from the exhibition spaces and the promotion that photographers were accustomed to. As compared with earlier times, the press gave ample attention to photography exhibitions, largely because they took place in the Palais des Beaux-Arts, and there were decent press contacts. Still, we have to keep in the back of our minds that the press releases were often written by participants in the exhibitions themselves.

Images Inventées was a collaboration with Steinert, and can be called a Belgian variant of his Subjektive Fotografie exhibitions. Steinert’s cooperation also acted as a guarantee of quality for the Palais des Beaux-Arts. The exhibition brought an international selection of modern art photography to the Palais. The house designer of the Palais des Beaux-Arts, Corneille Hannoset, was responsible for the layout of the catalogue and the hanging of the exhibition, with a budget that was more than most photographers were accustomed to. The photo exhibitions in the Palais des Beaux-Arts were the high points of Belgian modern art photography. Although there was never any official – i.e., financial – recognition, it was there that one of the most important steps was made in the battle for the acknowledgement of photography. This was the beginning of the era when photography would be taken seriously.

The Belgian photographers discussed above launched a consciousness-raising process in their country and offered the new generation of photographers the opportunity to develop their artistic aspirations without insurmountable difficulties. The period between 1965 and the 1970s was crucial, because it was during these years that photography received its first official support from the government, and began to be taught in art academies for the first time. Where in the 1950s and 1960s the photo clubs were still necessary for acquiring the technical and artistic knowledge for photography, a decade later there were many more possibilities open to photographers. Among those who comprised this new generation of photographers were Hubert Grooteclaes (1927-1994), Paul Ausloos (b. 1927), Walter De Mulder (b. 1933) and Paule Pia (b. 1920). Beginning in the late 1970s the Liège portrait photographer Hubert Grooteclaes, instructor in photography at the Institut supérieure des Beaux-Arts St. Luc in Liège, developed an international career. He became known for his photographismes and his characteristically out-of-focus images in sepia, lightly coloured with oil pencils. The Antwerp photographer and G 58 member Paul Ausloos, originally a painter and graphic designer, established a course in photography at the Academy in Sint-Niklaas in 1967, and was later an instructor at the Koninklijke Academie voor Schone Kunsten in Antwerp. In his personal work he attained prominence for his poetic still lifes, first in black and white, and later also in colour, which he carefully put together in the studio. The Ghent-based Walter De Mulder taught at the Sint-Lucas Instituut in Ghent and Brussels and at the Academy in Sint-Niklaas. He can be termed a subjective documentary photographer for his social-documentary reportage, landscapes and portraits of both artists and ‘normal’ people. He has received various distinctions, such as the World Press Photo prize. In the 1970s the Antwerp gallery owner Paule Pia, initially a fashion, theatre, ballet and portrait photographer, was occupied with creative and personal photography. In addition, the gallery which bore her name (1974-87) was a place where – in addition to its exhibitions by internationally renowned photographers – various Belgian photographers received their first chance to show their work. This was the era of autonomous photography, which found its home in photo galleries. The high point was in 1976, with the appearance of Filip Tas (1918-1997) as the first photographer to represent Belgium, at the 37th Venice Biënnale.

.

Dr. Tamara Berghmans

curator FotoMuseum Antwerpen en docent Vrije Universiteit Brussel

Noten

1. Mertens (2001), p. 58. ↑

2. This article is based on a part of the research for my doctoral dissertation: Berghmans (2008). ↑

3. There were not yet any requirements specified in law for practising the profession of photographer. The rapid development of photographic curricula in technical and art schools was a result of the introduction of legal regulations for the profession. On 17 April 1966, a law regarding establishing businesses came into force with legal conditions for practising the profession of photographer, which meant that one needed a diploma. Where previously one could acquire the necessary knowledge and skills at a photo club, there were now courses and training programmes set up to meet this requirement. See Sarlet (1988) and Sarlet (1993). ↑

4. Oosterbaan Martinius (1995). ↑

5. It was not until 1984 that the Museum for Modern Art was once again inaugurated. ↑

6. Geirlandt (2001), p. 48. ↑

7. [Exh. cat.] Images Inventées, Bruxelles: Palais des Beaux-Arts 1957.↑

8. [Exh. cat.] Images Inventées. La photographie créative belge dans les années 50, Bruxelles: Espace Photographique Contretype 1989; Van Deuren (1980); Van Luppen (2004). ↑

9. Steinert (1951), p. 7. ↑

10. Ibidem.↑

11. Steinert (1955); Eskildsen (1984); Koenig (1988); Herrmann (2001). ↑

12. Lemagny (1986), p. 190. ↑

13. Interview Johan Swinnen with Marcel Permantier, 1993, in Elias/Swinnen (1999), p. 159. ↑

14. Coulommier (1981), p. 241. ↑

15. Interview Johan Swinnen with Robert Besard, 1993, in Elias/Swinnen (1999), p. 89.↑

16. Eskildsen (2000); Eskildsen (1990). ↑

17. [Exh. cat.] 2ème Foire, Exposition de la Photo et du Cinema d’Amateur 1949/II. Messe, Ausstellung der Photo-Kino-Industrie 1949, Neustadt an der Haardt 1949.↑

18. [Exh. cat.] 11e Salon International Albert Ier (Cercle Royal photographique de Charleroi), Charleroi 1953; [Exh. cat.] subjektive fotografie, zweite internationale Ausstellung moderner Fotografie, veranstaltet von der Landeswerkkunstschule Saarbrücken (Direktor Prof. Dr. Steinert), Saarbrücken: Staatlichen Schule für Kunst und Handwerk 1954.↑

19. Interview Julien Coulommier, 12 February 2004.↑

20. Letter from Otto Steinert to Julien Coulommier, 13 May 1957 (personal archive of Julien Coulommier).↑

21. Letter from Otto Steinert to Julien Coulommier, 23 september 1957 (personal archive of Julien Coulommier).↑

22. [Exh. cat.] Festival d’Art photographique (Photo-Ciné Club de Boitsfort), Bruxelles: Hotel de Ville de Bruxelles 1955. ↑

23. [Exh. cat.] La photographie belge jugée par l’étranger (Filmart), Bruxelles: Maison des Arts 1958.↑

24. Interview Pierre Cordier, 19 June 2007.↑

25. Letter from Otto Steinert to Pierre Cordier, 1 March 1958 (personal archive of Pierre Cordier). ↑

26. Coulommier (1959), p. 270. ↑

27. Letter from Otto Steinert to Pierre Cordier, 15 June 1959 (personal archive of Pierre Cordier).↑

28. Geirlandt (1981), pp. 5-12. ↑

29. Images Inventées, Palais des Beaux-Arts, Bruxelles, Galerie “Aujourd’hui” (entrée: 23 rue Ravenstein), du 30 mars au 17 avril 1957. Vernissage zaterdag 30 maart, 14 uur, elke dag open van 10 tot 18 uur, entrée: 5 BEF.↑

30. Interview Julien Coulommier, 12 February 2004.↑

31. Statues de Bruxelles (par Marcel Broodthaers, textes; Julien Coulommier, photographies), Ixelles: Editions des Amis du Musée d’Ixelles 1987.↑

32. Personal communication by Julien Coulommier, 12 February 2004; Vausort 1998. ↑

33. Letter from Pierre Janlet to Otto Steinert, 14 January 1957 (personal archive of Julien Coulommier).↑

34. Letter from Pierre Janlet (in Dutch, French, English and German), 6 February 1957 (personal archive of Julien Coulommier)↑

35. Press release Images Inventées (personal archive of Julien Coulommier).↑

36. Julien Coulommier, Typescript ‘Inleiding’ for the exhibition Images Inventées (personal archive of Julien Coulommier).↑

37. Julien Coulommier, Typescript ‘Inleiding’ for the exhibition Images Inventées (personal archive of Julien Coulommier) .↑

38. Waal (1957). ↑

39. J.A. Schmoll Gen. Eisenwerth, in [Exh. cat.] Images Inventées, Bruxelles: Palais des Beaux-Arts 1957.↑

40. Schmoll (1952). ↑

41. Schmalriede (1984). ↑

42. Letter from Raoul Hausmann to Julien Coulommier, 14 April 1957 (personal archive of Julien Coulommier).↑

43. The exact duration of the exhibition at the Vrije Academie is not entirely clear. Different sources give various closing dates. The catalogue states: ‘La Haye, Vrije Academie du 25 mai au 20 juin 1957’; the invitation: ‘duur van de tentoonstelling: van 25 mei t/m 1 juli 1957’; and the poster: ’25 mei – 6 juli’.↑

44. Coulommier (1958). ↑

45. Coppens (1957). ↑

46. Website Städtische Museum Morsbroich, Leverkusen: <http://www.museum-morsbroich.de/index_htm.htm> consulted on 13 October, 2006.↑

47. Otto Steinert, in [Exh. cat.] Images Inventées (subjektive fotografie), Leverkusen: Städtische Museum Morsbroich 1958.↑

48. Interview Julien Coulommier, 12 February 2004; Interview Johan Swinnen with Julien Coulommier, 1993, in Elias/Swinnen (1999), p. 107.↑

49. De Loz/Cockx (1957), p. 13. ↑

50. De Nieuwe Gids 31 March 1957, Het Laatste Nieuws 30 March 1957 and La Nouvelle Gazette 14 April 1957.↑

51. Bilcke (1957). ↑

52. Van De Voorde (1957). ↑

53. Winkler Prins Encyclopedie (Coll. Boek van het jaar) Amsterdam/Brussel: Elsevier 1958, p. 140. ↑

54. Letter from Meinardus Woldringh to Julien Coulommier, 8 March 1957 (personal archive of Julien Coulommier).↑

55. Ruiter (1996); Rooseboom (1997). ↑

56. Coppens (1984), p. 138. ↑

57. Coppens (1957).↑

58. Ibid.↑

59. Hens (1957). ↑

Literature references

Berghmans, Tamara. Onderzoek naar de missie en de organisatie van de Belgische moderne kunstfotografie tussen 1950 en 1965. Geschiedenis en interpretatie van 7 strijdbare fotografen tussen traditie en vernieuwing (unpublished dissertation, Kunstwetenschappen en Archeologie), Brussel: Vrije Universiteit Brussel 2008.

Bilcke, Maurits. ‘Tentoonstellingen in Brussel’ Gazet van Antwerpen 3 April 1957.

C. [Martien Coppens]. ‘Images Inventées’, Fotografie 2 (1957), pp. 33-34.

Coppens, Martien. [Exh. cat.] “Subjektive Fotografie” Images of the 50’s, Essen: Folkwang Museum 1984.

Coulommier, Julien. ‘Fotografie op de Vrije Academie van Den Haag’, Foto 2 (1958), p. 48.

Coulommier, Julien. ‘Exit “Subjektive Fotografie”? …’, Foto 6 (1959), pp. 269-276.

Coulommier, Julien. ‘Subjectieve fotografie: mythe of begrip?’, Vlaanderen 184 (September/October 1981), pp. 241-242.

De Loz, Albert, and Guy Cockx. ‘Panorama des expositions’, Clic 14 (June 1957), pp. 13-15.

Elias, Willem, and Johan Swinnen. Fotografie in dialoog. Filosofie van de fotografie van Walter Benjamin tot Roland Barthes. Fotografie in België: inleiding en interviews, Kortrijk: Uitgeverij Groeninghe 1999.

Eskildsen, Ute. ‘“subjektive fotografie” a program of non-functionalized photography in post-war Germany’, in [Exh. cat.] “Subjektive Fotografie” Images of the 50’s, Essen: Folkwang Museum 1984, pp. 6-13.

Eskildsen, Ute. ‘Fotografische Ausbildung in Essen vor 1959 / Photographic Education in Essen before 1959’, in: [Exh. cat.] Otto Steinert und Schüler. Fotografie und Ausbildung 1948 bis 1978 / Otto Steinert and his Students. Photography and Education 1948 to 1978, Essen: Fotografische Sammlung im Museum Folkwang 1990, pp. 169-175.

Eskildsen, Ute (ed.). [Exh. cat.] Der Fotograf Otto Steinert, Götingen: Steidl/Museum Folkwang Essen 2000.

Exh. cat. Images Inventées. La photographie créative belge dans les années 50, Bruxelles: Espace Photographique Contretype 1989.

Exh. cat. 2ème Foire, Exposition de la Photo et du Cinema d’Amateur 1949/II. Messe, Ausstellung der Photo-Kino-Industrie 1949, Neustadt an der Haardt 1949.

Exh. cat. 11e Salon International Albert Ier (Cercle Royal photographique de Charleroi), Charleroi 1953.

Exh. cat. subjektive fotografie, zweite internationale Ausstellung moderner Fotografie, veranstaltet von der Landeswerkkunstschule Saarbrücken (Direktor Prof. Dr. Steinert), Saarbrücken: Staatlichen Schule für Kunst und Handwerk 1954.

Exh. cat. Festival d’Art photographique (Photo-Ciné Club de Boitsfort), Bruxelles: Hotel de Ville de Bruxelles 1955.

Exh. cat. La photographie belge jugée par l’étranger (Filmart), Bruxelles: Maison des Arts 1958.

Geirlandt, Karel J. ‘De Vereniging voor Tentoonstellingen van het Paleis voor Schone Kunsten bestaat vijftig jaar’, in: Een halve eeuw tentoonstellingen in het Paleis voor Schone Kunsten, Brussel: Vereniging voor tentoonstellingen van het Paleis voor Schone Kunsten 1981, pp. 5-22.

Geirlandt, Karel J. ‘Twintig jaar geleden’, in Karel J. Geirlandt (ed.), Kunst in België na 1945, Antwerpen: Mercatorfonds 2001, pp. 11-50.

Hens, J.J. ‘Images Inventées’, Foto 8 (1957), pp. 301-302.

Herrmann, Ulrike. Otto Steinert und sein fotografisches Werk. Fotografie im Spannungsfeld zwischen Tradition und Moderne (dissertation 1999, Rühr-Universität Bochum), Kassel: University Press 2001.

Koenig, Thilo. Otto Steinerts Konzept ‘Subjektive Fotografie’ (1951-1958), Munich: Tuduv Studien 1988.

Lemagny, Jean-Claude. ‘La photographie inquiète d’elle-même (1950-1980)’, in Jean-Claude Lemagny and André Rouillé (eds.), Histoire de la Photographie, Paris: Bordas 1986, pp. 187-211.

Mertens, Phil. ‘1945-60’, in Karel J. Geirlandt (ed.), Kunst in België na 1945, Antwerpen: Mercatorfonds 2001, pp. 53-103.

Oosterbaan Martinius, Warna. ‘De amateurs en de regels van de kunst. Discussies over amateurfotografie tussen 1945 en 1975’, in Stilstaande beelden. Ondergang en opkomst van de fotografie (Kunst en beleid in Nederland 7), Amsterdam: Boekmanstudies/Van Gennep 1995, pp. 163-175.

Rooseboom, Hans. ‘Meinard Woldringh, de NFK en de Subjektive Fotografie, 1950-1958’, in Jong Holland 13 (1997) 4, pp. 48-58.

Ruiter, Tineke de. ‘De Nederlandsche Fotografen Kunstkring, 1902-1948’, in Ingeborg Leijerzapf (ed.), Geschiedenis van de Nederlandse fotografie in monografieën en thema-artikelen, no. 27 (1996), Amsterdam: Voetnoot.

Sarlet, Jean-Michel. La photographie dans la Communauté française de Belgique après 1945 (unpublished licentiate thesis), Liège: Université de Liège 1988.

Sarlet, Jean-Michel. ‘Des années 50 aux années 70. De l’individuel au collectif, de la marginalité à une relative légitimité’, in Georges Vercheval (ed.), Pour une histoire de la Photographie en Belgique. Essais critiques – Répertoire des photographes depuis 1839, Charleroi: Musée de la photographie 1993, pp. 117-129.

Schmalriede, Manfred. ‘“subjektive fotografie” and its relation to the twenties’, in [Exh. cat.] “Subjektive Fotografie” Images of the 50’s, Essen: Folkwang Museum 1984, pp. 22-27.

Schmoll Gen. Eisenwerth, J.A. ‘Objektive und subjektive Fotografie’, in Otto Steinert (ed.), Subjektive Fotografie, ein Bildband moderner europäischer Fotografie / Un recueil de photographies modernes européennes / A Collection of Modern European Photography, Bonn/Rhein: Brüder Auer Verlag 1952, pp. 8-12.

Steinert, Otto. ‘Vorwort’, in [Exh. cat.] Subjektive Fotografie, Internationale Ausstellung moderner Fotografie, Saarbrücken: Staatliche Schule für Kunst und Handwerk 1951, p. 5-8.

Steinert, Otto (ed.). subjektive fotografie 2, ein Bildband moderner Fotografie / un recueil de photographies modernes / a collection of modern photography, Munich: Brüder Auer Verlag 1955.

U.V. [Urbain Van De Voorde]. ‘Tentoonstellingen te Brussel. Abstracte kunst’ De Standaard 6 April 1957.

Van Deuren, Karel. [Exh. cat.] De fotografie in België 1940-1980, Antwerpen: Het Sterckshof 1980.

Van Luppen, Hilde. Een fotohistorisch onderzoek van ‘Fotografische Kring IRIS’ 1908-1987 (unpublished licentiate thesis), Brussel: Vrije Universiteit Brussel 2004.

Vausort, Marc. [Exh. cat.] Serge Vandercam, Photographe Cobra, Charleroi: Musée de la Photographie 1998.

Waal, Hans van de. ‘De wereld waarin wij leven’, in [Exh. cat.] Images Inventées, Bruxelles: Palais des Beaux-Arts 1957.